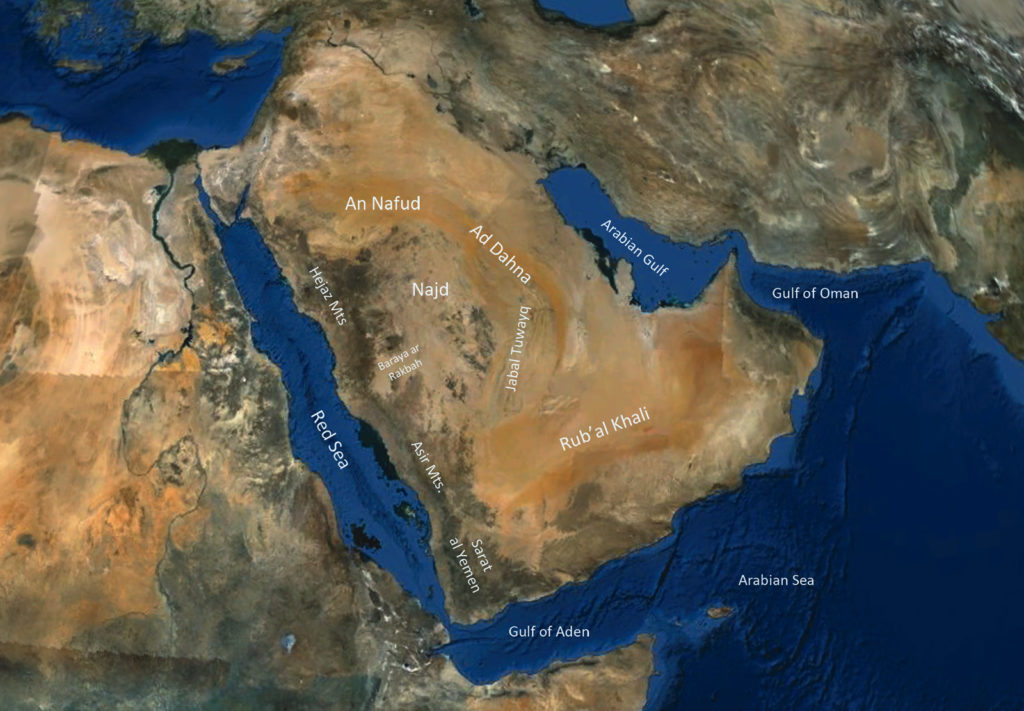

The Arabian Peninsula has served as both a land bridge and a center for indigenous cultural development for hundreds of thousands of years. Its central location, with Africa to the west and Asia to the east, gave it a critical role in human history that can best be absorbed by a closer look at its geography. To elucidate the human history of the Arabian Peninsula, it is therefore beneficial to understand the most prominent features of the region. By way of a brief introduction, a few geographical terms will be defined and place names described. Map 1 identifies the locations of the most prominent features.

Deserts

The Arabian Desert may be divided into three key parts, An Nafud, Ad Dahna, and Rub’ al Khali. An Nafud is the northernmost of these three. Found in north-central Saudi Arabia, it is a vast oval sand sea (68,000 km2 in area) characterized by large, deep red, crescent-shaped dunes. It measures 300-400 km east-west and 125-250 km north-south.

Noted for its sudden high winds and sandstorms, An Nafud is an erg, or large sand sheet dotted with scrub and small trees. Rain falls here only once or twice a year. However, oases on its western edge, where it meets the Hejaz Mountains, may produce dates and other fruits, as well as vegetables and grain. Tayma is a large oasis on the western margin of An Nafud that was an important starting or ending point for travelers crossing this hostile desert. Rock art distributed around the vicinity of Tayma records the stories of those who passed by through the centuries. The oasis of Jubbah provided an important way station on the south-central perimeter of An Nafud. The Blunts reported hare and oryx in the central Nafud, and Carruthers found tracks of ostriches there in 1935 (Garrard and Harvey 1981).

Lady Anne Blunt was the first European woman to cross An Nafud, in 1878. In her journal, she described her impressions of this great desert in detail. Although she dreaded it initially and was exhausted at the end, she was struck by its beauty:

The thing that strikes one first about the Nafud is its color. It is not white like the sand dunes we passed yesterday, nor yellow as the sand is in parts of the Egyptian desert, but a really bright red, almost crimson in the morning when it is wet with dew… It is however a great mistake to suppose it barren. The Nafud, on the contrary, is better wooded and richer in pasture than any part of the desert we have passed in leaving Damascus. It is tufted all over with ghada bushes, and bushes of another kind called yerta...” A Pilgrimage to Nejd, Anne Blunt, 1881.

The central part of the Arabian Desert, the Ad Dahna is a long, narrow crescent of sand dunes that connects An Nafud in the north to Rub’ al Khali in the south. It is 1,200 km long, north to south, and a mere 24-80 km wide, with red dunes oriented perpendicular to its axis referred to as veins. The Ad Dahna runs along the eastern edge of the Jabal Tuwayq range.

The Rub’ al Khali, known in English as the Empty Quarter, covers an incredible 650,000 km2 (1,000 km long and 500 km wide) and is the largest sand desert in the world. Occupying over a third of the peninsula, it spans the southeastern part of Saudi Arabia, as well as parts of Yemen, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates. Elevations run from 800 m in the southwest to around sea level in the northeast. For the most part, the Rub’ al Khali is covered in enormous reddish-orange sand dunes, reaching up to 250 m in height. Remnants of ancient lakes, expressed as hard pans of calcium carbonate, gypsum, marl or clay, provide evidence of a lusher environment and gentler climate between 6,000-2000 years ago. Sites dating to the Lower Pleistocene have yielded remains of fish, hippopotamus, and water buffalo. Today, this vast sand sea has a hyper-arid climate with an average high temperature of 47o Cand maximum high of around 56o C. The average annual precipitation is only around 30 mm currently. Our research in the Bi’r Hima region skirted the westernmost edge of the Rub’al Khali.

Mountains and Plateaus

The Sarawat is the largest mountain range on the Arabian Peninsula, stretching from the border between Jordan and Saudi Arabia, down to the Gulf of Aden, in Yemen, along the western edge of the Arabian Peninsula. The range is part of the Arabian Shield and is primarily volcanic rock. The northern part, known as the Hejaz, or “barrier,” is lower than the rest, with peaks generally under 2600 m. The central part, the Asir, and the southern part, Sarat al Yemen, have elevations rising up to 3,600 m. The western slopes of the Sarawat Mountains plunge steeply to the Red Sea coastal plain, while on the eastern side, they descend more gradually. Wadis that dissect the eastern slopes of the highlands support agriculture in the south, where they are touched by monsoons.

The Najd, which means “highland,” is a vast plateau that occupies most of the center of the Arabian Peninsula. Definitions of its borders have fluctuated through history, but the Sarawat mountain range defines its western edge. The Ad Dahna desert provides the eastern boundary, and the Rub’ al Khali the southern border. It stretches 885 km north to south and 725 km east to west, with a total area of 470,000 sq. km. The Najd slopes downward from the southwest to northeast with elevations ranging from 1525-760 m. The eastern part is more fertile and better suited for agriculture, with greater numbers of oases than the west. As a result, the east has more permanent settlements, while the west is sparsely occupied by Bedouin herders. Ha’il Province, which has yielded so many petroglyphs, is located in the northern part of the Najd. The petroglyph outcrop Qaryat al Asba, near Riyadh, is more southeasterly.

Jabal Tuwayq is a long, narrow escarpment that runs for 800 km through the Najd in central Arabia. Rising up to 600 m in elevation, it is actually a narrow plateau that slopes gradually downward to the east, with its sharp cliff edge facing westward. The central part is mostly Jurassic in age and possesses enormous oil reserves. Riyadh is adjacent to this geological feature and the petroglyph site of Qaryat al Asba lies southwest of Riyadh.

Lava Fields

Due to rifting between the Arabian and African Tectonic Plates that formed the Red Sea starting around 40 million years ago, the earth’s crust has been stretched laterally, causing a vast basalt province. As a result, there are numerous large patches of lava fields, known by the term harrat, (the plural is harra), distributed from north to south over much of the western part of the Kingdom. Running roughly parallel to the Red Sea coast, the biggest and best-known harra are: Ash Shamah, Uwayrid, Ithnayn, Khaybar and Kura, Rahat, Kishb, Hadan, Nawasif, Buqum, and Al Birk.

Some harra have been active in historic times, impacting human settlements. One of the most notable events happened in 1256 CE, when six scoria cones in the large Harrat Rahat erupted, sending a lava flow to within just 4 km of the holy city of Madinah.

The historic oasis of Tayma is located at the base of the Harrat al Uwayrid. The explorer Charles Montagu Doughty described his observations of these lava fields during his two-year trek across Arabia (1876-78) in his famous book Arabia Deserta (1888: 419):

Viewing the great thickness of lava floods, we can imagine the very old beginning of the Harra-those streams upon streams of basalt, which appear in the calls of some wady-breaches of the desolate Aueyrid.

The rock art of Shuwaymis, in southwest Ha’il Province, is on Cambrian sandstone protruding from basaltic lava fields in the Harrat Khaybar. Shuwaymis is also in close proximity to the Harrat Ithnayn, which is one of the more recent fields, having begun only around 3 million years ago. Its latest flows are known to have occurred within the last 4500 years, but there may have been eruptions as recently as 1500 years ago. As a result, it is likely that the artists who created the images at Shuwaymis moved through a somewhat different terrain than exists today.

Plains

Baraya ar Rakbah is a great sand plain that emerges south of the Harrat Kishb. It consists of an extremely flat region with little vegetation and a low population density. It is directly east of the cities of Jeddah and Makkah, and south of Madinah.

Coasts

The vast Arabian Desert, so destitute of freshwater, is ironically nearly surrounded by seas. These include the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Arabian Sea, Gulf of Oman, and Arabian Gulf. In addition, the Mediterranean Sea was accessible through the Levant via trade routes. Arabia’s long coastlines provide important resources, including fish, shellfish, pearls, and, with the invention of sea craft, a means of reaching other lands.