"If the 'black box' flight recorder is never damaged during a plane crash, then why isn't the whole airplane made out of that stuff?"

This famous quote from comedian George Carlin may be fun to bring up when commiserating with others over travel anxieties, but the truth is that black boxes are hugely impressive feats of engineering that are anything but taken lightly when it comes to aviation safety. Feel better about your next flight, thanks to these facts—but maybe don't bring them up as small talk with your seat mate until you've landed.

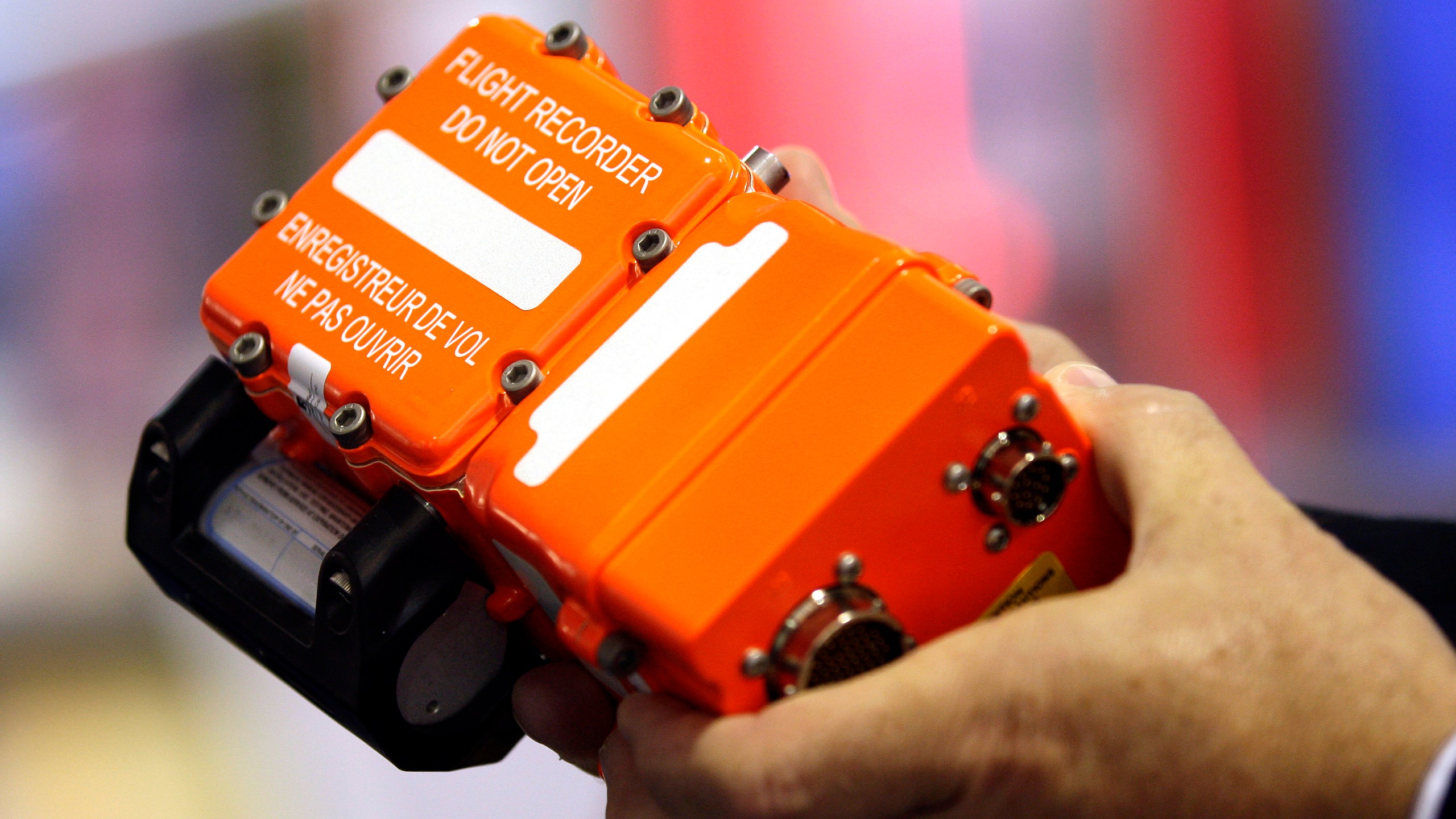

Black boxes are not black.

Flight recorders must be highly visible to aid in quick location and recovery, so they're actually a very eye-catching shade of orange. Tony Nardone, president at L3 Aviation Products, tells Condé Nast Traveler that "all recorders are painted bright orange and have reflective striping similar to road signs, which aids in visual identification." The term "black box," says Nardone, is widely-accepted after having been "popularized by media coverage over the years," but it originated with the black color of a recorder, nicknamed the "Mata Hari," made by Finnish aviation engineer Veijo Hietala in 1942.

They’ve been recording since the dawn of the jet age.

According to flight recorder producer Curtiss-Wright, the first of the truly modern style of recorders, with reusable memory and impact protections, was introduced in 1957, the same year Boeing debuted the 707 and kicked the jet age into high gear. It utilized magnetic tape recording and was the first to combine the storage of both information from flight instruments and cockpit voice recording. These days, recorders employ flash-memory-based, solid-state technology for the recording, which is much more reliable.

They are seriously tough.

Before a model of a flight recorder is approved, it goes through a barrage of brutal tests to ensure its survivability. Everything from resistance to salt water and chemical corrosion to deep sea crush pressure is measured. Curtiss-Wright’s testing facilities are a veritable dungeon of impact, fire, and spike penetration devices for testing their recorders, which fly in everything from fighter jets of the UK’s Royal Air Force to Boeing Chinook military helicopters.

At L3 Aviation Products, Nardone confirms to Traveler that “recorders are certified to continuously operate between -55°and +70°C, and altitudes of -1,000 to 55,000 feet. They must survive a fire exposure of 1,100° C (2,012° F) for 60 minutes, and withstand an impact of 3,400 gs.” For comparison’s sake, a car crash might put 50 to 75gs of force on a human—and that’s without a guarantee of survival.

Nardone also points out that recorders are primarily constructed of aluminum, for weight savings, but the memory–the most important bit–is “surrounded by a stainless steel or titanium housing for impact protection, as well as thick layers of thermal insulation for fire protection.” L3’s Model FA2100, standard equipment on most airliners, weighs just under 11 pounds and has a “100 percent success rate in recovering data from airline incidents," says Nardone.

French is their second language.

The black box’s orange exterior typically sports reflective decals and the command “do not open.” It can be opened, but doing so is left to authorities independent of the airlines, to ensure the memory is not compromised. In addition to English, however, the words may be repeated in French. Although the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), an entity of the United Nations which sets standards and practices, officially made English the universal language of the skies in 2001, French is still prevalent in aviation, and even ICAO itself is headquartered in French-speaking Quebec.

Anyone can own one.

Although Nardone notes that one flight recorder unit is typically valued at $30,000, there is a market for used black boxes that have reached the end of their flying lives. Aviation artifact repurposing companies like Aerodite salvage flight recorders from retired aircraft, saving the units from scrapping to re-introduce them as objets d’art. A used flight recorder from a Boeing 757, for example, becomes a high-tech doorstop and instant conversation-starter.

Advancements in technology are only making them better.

The solid-state memories inside of black boxes currently record an average of two hours of high-quality cockpit voice and data, which is recorded over as a flight progresses without incident. If an accident occurs and a standard recorder is submerged, a locator beacon activates and emits an ultrasonic acoustic signal for 30 days, during which time recovery will hopefully occur. That signal has been improved, and now 90 days of uninterrupted operation is possible with select newer models.

There’s even the ability to see exactly what was happening in the cockpit, rather than just relying on a recording of what was said. Curtiss-Wright's video black box system is dubbed “AIR,” or Airborne Image Recorder, which does exactly what it sounds like: In addition to storing cockpit audio, the box also takes in up to two hours of color, HD images at four frames per second. It’s far from a GoPro for vacation selfies; the camera is focused on the controls and command movements of the flight crew.

Someday soon, even the black box as we know it may be made obsolete, thanks to developments in streaming of flight data. The mind-boggling tragedy of flight MH370, which went missing in the Indian Ocean in 2014 and has yet to be found, underscored the need for such "black box in the cloud" technology, but there are privacy as well as price roadblocks before airlines can fully listen in on the cockpits of their planes in real-time.