When this canvas appeared at public auction in 1983, it was catalogued as a painting of Tarquin and Lucretia from the circle of Simon Vouet. Almost immediately, however, it was recognized as an early work by Vouet’s student Le Sueur, and the identification of the subject was questioned. The facial types and palette are characteristic of Le Sueur. On the other hand, the energetic poses of the almost lifesize figures, set before a heavily draped canopy bed, recall Vouet’s compositions of the 1620s, such as his lost painting of the

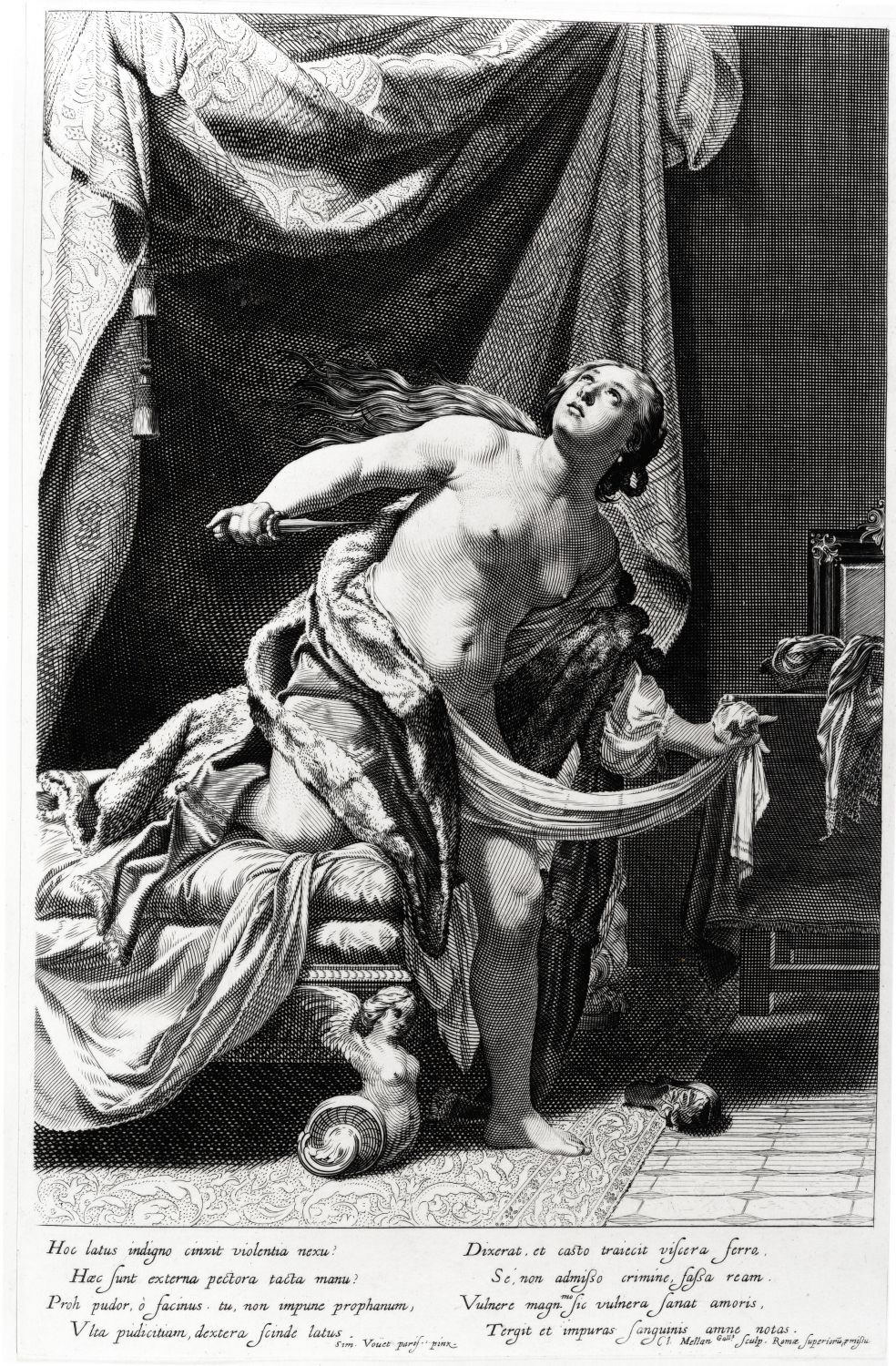

Death of Lucretia, known from an engraving by Claude Mellan (The Met,

45.97(76); see fig. 1 above). The affinity with Vouet suggests a fairly early date in Le Sueur’s career, probably while he was still working in Vouet’s studio (ca. 1632–42).

At first glance, the painting appears to represent the rape of the virtuous Roman matron Lucretia. Yet according to Livy (History of Rome 1.58), Tarquin threatened to slay Lucretia’s male servant and, if she did not submit to him, to declare that he had discovered them together in bed. The servant in the present painting is a young woman, not a man; moreover, it is unclear why the rapist holds a cup in his left hand. An alternative subject is the story of Amnon and Tamar, a rare Old Testament subject that calls for nude figures. Amnon, who had fallen in love with his half-sister Tamar, told his father, King David, that he was ill and requested that she prepare his food. When they were alone, he then coerced her to sleep with him, but overcome with revulsion for what he had done, he then forced her to leave him (2 Samuel 13:1–22). The preparation of a meal may explain the presence of the cup and the overturned urn of water in the foreground. The Bible also speaks of Tamar’s “garment of divers colors,” which accords with the woman’s ocher dress and blue mantle. But there is no mention of a dagger. Indeed, in the few known depictions of Tamar and Amnon, artists such as Guercino (National Gallery of Art, Washington) portray the most unusual element of the story, Amnon repudiating Tamar after he had slept with her. The flailing arms and violent action in Le Sueur’s painting recall the

Rape of Lucretia that Titian (ca. 1485/90?–1576) painted in 1571 for Philip II of Spain (now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge). Le Sueur might have seen the workshop version of it in the collection of Cardinal Mazarin (now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux) or Cornelis Cort’s engraving after the original (The Met,

49.97.539).

Although the original destination of the painting is unknown, it likely formed part of a decorative cycle installed in the wainscoting of a room in a Parisian townhouse. The fluted pilasters of the painted architecture recall the grandiloquent interiors of the buildings of Louis Le Vau (1612–1670), the architect of the Hôtel Lambert, for which Le Sueur would later produce some of his finest works.

[2011; adapted from Fahy 2005]