Biogenesis vs. Spontaneous Generation

- 1. Biogenesis vs. Spontaneous Generation 1 How do organisms come into being?

- 2. The History • The principle of biogenesis, which states that all living things come from other living things, seems very reasonable to us today. • Before the 17th century, however, it was widely thought that living things could also arise from nonliving things in a process called spontaneous generation. 2

- 3. The History • For centuries, people accepted spontaneous generation as the explanation for the sudden appearance of some organisms. For example, it was believed that maggots arose from the meat, mice from the grain, and beetles from the dung. When fish appeared in ponds that had been dry the previous season, people thought mud might have given rise to the fish. 3

- 4. The Experiments • In attempting to learn more about the process of spontaneous generation, scientists performed controlled experiments. 4

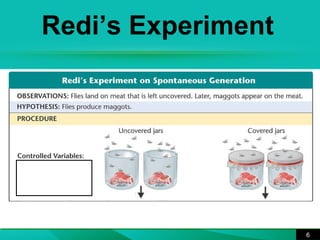

- 5. Redi’s Experiment • In the middle of the 17th century, the Italian scientist Francesco Redi noticed and described the different developmental forms of flies. • Redi observed that tiny wormlike maggots turned into sturdy oval cases, from which flies eventually emerge. • He also observed that maggots seemed to appear where adult flies had previously landed. • In 1668, Redi proposed a different hypothesis: that maggots came from eggs that flies laid on meat. 5

- 8. New Discovery • At about the same time that Redi carried out his experiment, other scientists began using a new tool—the microscope. – Their observations revealed that the world is teeming with tiny creatures. – They discovered that microorganisms are simple in structure and amazingly numerous and widespread. – Many investigators at the time thus concluded that microorganisms arise spontaneously from a “vital force” or “life force” in the air. 8

- 9. New Discovery – Anton van Leeuwenhoek of the Netherlands discovered a world of tiny moving objects in rainwater, pond water, and dust. Inferring that these objects were alive, he called them “animalcules,” or tiny animals. He made drawings of his observations and shared them with other scientists. 9

- 10. Needham’s Experiment • In the mid-1700s, John Needham, an English scientist, used an experiment involving animalcules to attack Redi’s work. • Needham claimed that spontaneous generation could occur under the right conditions. • To prove his claim, he sealed a bottle of gravy and heated it. • He claimed that the heat had killed any living things that might be in the gravy. • After several days, he examined the contents of the bottle and found it swarming with activity. • He inferred that “these little animals can only have come from juice of the gravy.” 10

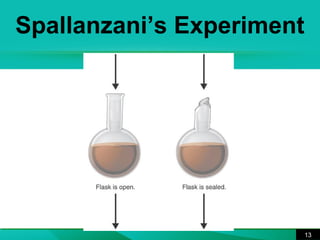

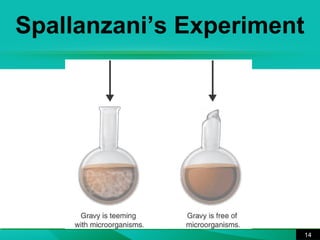

- 11. Spallanzani’s Experiment • In the 1700s, another Italian scientist, Lazzaro Spallanzani, designed an experiment to test the hypothesis of spontaneous generation of microorganisms. • He thought that Needham had not heated his samples enough and decided to improve upon Needham’s experiment. • Spallanzani hypothesized that microorganisms formed not from air but from other microorganisms. 11

- 12. Spallanzani’s Experiment 12 CCoonnttrrooll GGrroouupp EExxppeerriimmeennttaall GGrroouupp

- 15. Spallanzani’s Experiment • Spallanzani concluded that nonliving gravy did not produce living things. The microorganisms in the unsealed jar were offspring of microorganisms that had entered the jar through the air. • This experiment and Redi’s work supported the hypothesis that new organisms are produced only by existing organisms. – Spallanzani’s opponents, however, objected to his method and disagreed with his conclusions. – They claimed that Spallanzani had heated the experimental flasks too long, destroying the “vital force” or “life force” in the air inside them. Air lacking this “vital force” or “life force,” they claimed, could not generate life. – Thus, those who believed in spontaneous generation of microorganisms kept the idea alive for another century. 15

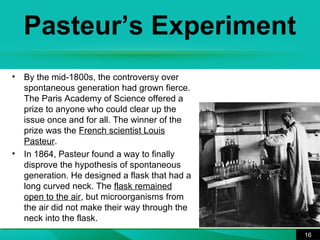

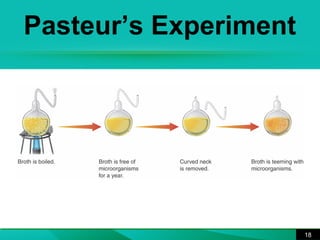

- 16. Pasteur’s Experiment • By the mid-1800s, the controversy over spontaneous generation had grown fierce. The Paris Academy of Science offered a prize to anyone who could clear up the issue once and for all. The winner of the prize was the French scientist Louis Pasteur. • In 1864, Pasteur found a way to finally disprove the hypothesis of spontaneous generation. He designed a flask that had a long curved neck. The flask remained open to the air, but microorganisms from the air did not make their way through the neck into the flask. 16

- 17. Pasteur’s Experiment • Pasteur boiled the flask thoroughly to kill any microorganisms it might contain. • Pasteur waited an entire year. In that time, no microorganisms could be found in the flask. • About a year after the experiment began, Pasteur broke the neck of the flask, allowing air dust and other particles to enter the broth. • In just one day, the flask was clouded from the growth of microorganisms. 17

- 19. Pasteur’s Experiment • Pasteur had clearly shown that microorganisms had entered the flask with particles from the air. • His work convinced other scientists that the hypothesis of spontaneous generation was not correct. • With Pasteur’s experiment, the principle of biogenesis (all living things come from other living things) became a cornerstone of biology. 19

- 20. The Impact of Pasteur’s Work 20 • Pasteur made many discoveries related to microorganisms. His research had an impact on society, as well as, on scientific thought. − He saved the French wine industry, which was troubled by unexplained souring of wine, and the silk industry, which was endangered by a silkworm disease. − Moreover, he began to uncover the very nature of infectious diseases, showing that they were the result of microorganisms entering the bodies of the victims. • Very short biographical video clip of Pasteur’s work: http://www.biography.com/people/louis-pasteur-9434402