harappan civilization

- 2. Introduction Sites of Harappan Civilization Mohenjo-Daro : courtyard and alley Dholavira : main features and sign board Lothal Chanhudaro : crafts industry & facts and artefacts Art of Civilization : artistic features & products and artefacts Harappan seals : indication of seals and important seals End of Civilization Conclusions

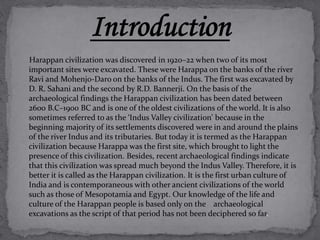

- 3. Harappan civilization was discovered in 1920–22 when two of its most important sites were excavated. These were Harappa on the banks of the river Ravi and Mohenjo-Daro on the banks of the Indus. The first was excavated by D. R. Sahani and the second by R.D. Bannerji. On the basis of the archaeological findings the Harappan civilization has been dated between 2600 B.C–1900 BC and is one of the oldest civilizations of the world. It is also sometimes referred to as the ‘Indus Valley civilization’ because in the beginning majority of its settlements discovered were in and around the plains of the river Indus and its tributaries. But today it is termed as the Harappan civilization because Harappa was the first site, which brought to light the presence of this civilization. Besides, recent archaeological findings indicate that this civilization was spread much beyond the Indus Valley. Therefore, it is better it is called as the Harappan civilization. It is the first urban culture of India and is contemporaneous with other ancient civilizations of the world such as those of Mesopotamia and Egypt. Our knowledge of the life and culture of the Harappan people is based only on the archaeological excavations as the script of that period has not been deciphered so far.

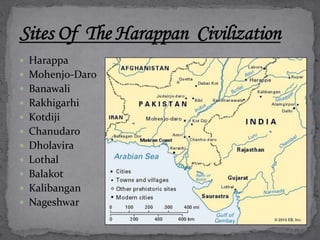

- 4. Harappa Mohenjo-Daro Banawali Rakhigarhi Kotdiji Chanudaro Dholavira Lothal Balakot Kalibangan Nageshwar

- 5. Mohenjo-Daro, or "Mound of the Dead" is an ancient Indus Valley Civilization city that flourished between 2600 and 1900 BCE. It was one of the first world and ancient Indian cities. The site was discovered in the 1920s and lies in Pakistan's Sind province. Mohenjo-Daro, is an ancient planned city laid out on a grid of streets. An orthogonal street layout was oriented toward the north-south & east-east directions: the widest streets run north-south, straight through town; secondary streets run east-west, sometimes in a staggered direction. Secondary streets are about half the width of the main streets; smaller alleys are a third to a quarter of the width of the main streets

- 6. COURTYARD HOUSE The house was planned as a series of rooms opening on to a central courtyard providing an open space inside for community activities. There were no openings toward the main street – only rather small openings to the side streets. . Brick stairways provided access to the upper floors or rooftop gardens. The houses are believed to have flat, timber roofs. Houses built with a perimeter wall and adjacent houses were separated by a narrow space of land. There were just a few fairly standardized layouts, perhaps an indication of a fairly egalitarian society. But not all houses had two stories and only the larger houses have their own wells. There are also rows of single-roomed barracks, perhaps for singles, soldiers or slaves.

- 7. The large platform, called the ‘Citadel’ is presumed to be the administrative seat. Other public buildings are temples and public baths. There are also granaries where the stores are elevated above brick platforms that have ventilation ducts. Separated from the domestic areas are the artisan workshops. The street layout shows an understanding of the basic principles of traffic, with rounded corners to allow the turning of carts easily. The drains are covered. The city probably had around 35,000 residents

- 8. Being one among the five largest Harappan cities in the subcontinent, Dholavira has yielded many firsts in respect of Indus civilization. Fourteen field seasons of excavation through an enormous deposit caused by the successive settlements at the site for over 1500 years during all through the 3rd millennium and unto the middle of the 2nd millennium BC have revealed seven significant cultural stages documenting the rise and fall of the Indus civilization in addition to bringing to light a major, a model city which is remarkable for its exquisite planning, monumental structures, aesthetic architecture, amazing water harvesting system and a variety in funerary architecture. It also enjoys the unique distinction of yielding an inscription made up of ten large-sized signs of the Indus script and, not less in importance, is the other find of a fragment of a large slab engraved with three large signs. This paper attempts to give an account of hydro-engineering that is manifest in the structures of the Harappans at Dholavira

- 9. Main features The salient components of the full-grown cityscape consisted of a bipartite 'citadel', a 'middle town' and a 'lower town', two 'stadia', an 'annexe', a series of reservoirs all set within an enormous fortification running on all four sides. Interestingly, inside the city, too, there was an intricate system of fortifications. The city was, perhaps, configured like a large parallelogram boldly outlined by massive walls with their longer axis being from the east to west. On the bases of their relative location, planning, defenses and architecture, the three principal divisions are designed tentatively as 'citadel', 'middle town', and 'lower town'. The citadel at Dholavira, unlike its counterparts at Mohenjo-Daro, Harappa and Kalibangan but like that at Banawali, was laid out in the south of the city area. Like Kalibangan and Surkotada it had two conjoined subdivisions, tentatively christened at Dholavira as 'castle' and 'bailey', located on the east and west respectively, both are fortified ones

- 10. Sign board?? Generally Harappan inscriptions are short containing only four letters or less than four letters . However this above given sign board of Dholavira is different , it contains 10 letters and is quite lengthy compared to inscriptions on seals of Harappan civilization. Analysis of this inscription shows that most probably the objective of the sign board is different from the regular Indus seals encountered so far. The place of finding of an object in the archaeological site is important to interpret the nature of an object. Historians’ interpretation is that "Dholavira" is a "burial place" , because it is being described as "Dholavira -Bhoot Pradesh” . Further, a skeleton was found in a sitting position near this "Dholavira sign Board" (as per the information given by guide, not yet verified). "Bhoot Pradesh" shows that Dholavira was a kind of burial place and not a place for living people. What some other archaeologists interpret about the "Signboard " is that it could be indicating the name of the person, who had been buried in this place. Further, excavation below this sign board will reveal that there is the possibility of finding a skeleton below that sign board. The sign board is nothing but a "epitaph"(An inscription on a tombstone in memory of the of a dead person over his grave). The analysis of the symbols involved shows that this signboard has been written in the last phase of "Indus Valley civilization" and impact of Sanskrit words could be easily visualized.

- 11. Lothal A flood destroyed village foundations and settlements (c. 2350 BCE). Harappan’s based around Lothal and from Sindh took this opportunity to expand their settlement and create a planned township on the lines of greater cities in the Indus valley. Lothal planners engaged themselves to protect the area from consistent floods. The town was divided into blocks of 1–2- metre-high (3–6 ft) platforms of sun-dried bricks, each serving 20–30 houses of thick mud and brick walls

- 12. The city was divided into a citadel, or acropolis and a lower town. The rulers of the town lived in the acropolis, which featured, paved baths , underground and surface drains (built of kiln-fired bricks) and a potable water well. The lower town was subdivided into two sectors — the north-south arterial street was the main commercial area — flanked by shops of rich and ordinary merchants and craftsmen. The residential area was located to either side of the marketplace. The lower town was also periodically enlarged during Lothal's years of prosperity. Lothal engineers accorded high priority to the creation of a dockyard and a warehouse to serve the purposes of naval trade. While the consensus view amongst archaeologists identifies this structure as a "dockyard," it has also been suggested that owing to small dimensions, this basin may have been an irrigation tank and canal. The dock was built on the eastern flank of the town, and is regarded by archaeologists as an engineering feat of the highest order. It was, located away from the main current of the river to avoid silting, but provided access to ships in high tide as well. The warehouse was built close to the acropolis on a 3.5-metre-high (10.5 ft) podium of mud bricks. The rulers could thus supervise the activity on the dock and warehouse simultaneously. Facilitating the movement of cargo was a mud-brick wharf,220 metres (720 ft) long, built on the western arm of the dock, with a ramp leading to the warehouse. There was an important public building opposite to the warehouse whose superstructure has completely disappeared. Throughout their time, the city had to brace itself through multiple floods and storms.

- 13. Lothal has enjoyed the status of being the leading center of trade in the bygone times. It was actively involved in the trade of beads, gems and expensive ornaments that were exported to West Asia and Africa. The techniques that were used by the people of this city brought a lot of name and fame to them. People are of the say that, the scientists of Lothal were the ones to initiate the study of stars and advanced navigation.

- 14. Chanhudaro Chanhudaro is an archaeological site belonging to the post-urban Jhukar phase of Harappan civilization. The site is located 130 kilometers south of Mohenjo- Daro, in Sindh, Pakistan. The settlement was inhabited between 4000 and 1700 BCE, and is considered to have been a centre for manufacturing carnelian beads. This site is a group of three low mounds that excavations has shown were parts of a single settlement, approximately 5 hectares in size. Chanhudaro was first excavated by Nani Gopal Majumdar in March, 1930. Chanhudaro is about 12 miles east of present day Indus river bed. Chanhu-Daro was investigated in 1931 by the Indian archaeologist N. G. Majumdar. It was observed that this ancient city was very similar to Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro in several aspects like town planning, building layout etc. The site was excavated in the mid-1930s by the American School of Indic and Iranian Studies and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, where several important details of this ancient city was investigated

- 15. Craft industry and facts Evidence of shell working was found at Chanhudaro and bangles and ladles were made at this site. Harappan seals were made generally in bigger towns like Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro and Chanhudaro which were involved with administrative network. An Impressive workshop, recognized as Bead Making Factory, was found at Chanhudaro, which included a furnace. Shell bangles, beads of many materials, steatite seals and metal works were manufactured at Chanhudaro. Copper knives, spears, razors, tools, axes, vessels and dishes were found, inspiring this site to be nicknamed as "Sheffield of India". Copper fish hooks were also recovered from this site. Terracotta cart model, small terracotta bird when blown acts as vistle, plates, dishes were found. Male spear thrower or dancer - a broken statue (4.1 cm) is of much importance, found at Chanhudaro, Indus Seals are also found at Chanhudaro. For building houses, baked bricks were used extensively at Chanhudaro and Mohenjo-Daro. Several constructions were identified as work shops or industrial quarters and some of the buildings of Chanhudaro might have been warehouses.

- 16. .

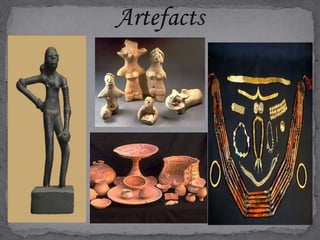

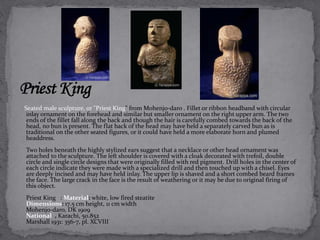

- 18. The Harappans were not on the whole extravagant in their art. The inner walls of their houses were coated with mud plaster without paintings. The outer walls facing the streets were apparently of plain brick. Architecture was austerely utilitarian. Their most notable artistic achievement was perhaps in their seal engravings, especially those of animals, e.g., the great urns bull with its many dewlaps, the rhinoceros with knobbles armored hide, the tiger roaring fiercely, etc. The Harappans were expert bead-makers. The potter's wheel was in full use. The red sandstone torso of a man is particularly impressive for its realism. The bust of another male figure, in steatite, seems to show an attempt at portraiture. However, the most striking of the figurines is perhaps the bronze 'dancing girl, found in Mohenjo-daro. Naked but for a necklace and a series of bangles almost covering one arm, her hair dressed in a complicated coiffure, she stands in a provocative posture, with one arm on her hip and one lanky leg half-bent.

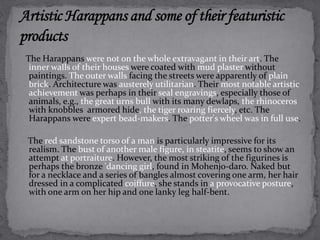

- 19. Seated male sculpture, or "Priest King" from Mohenjo-daro . Fillet or ribbon headband with circular inlay ornament on the forehead and similar but smaller ornament on the right upper arm. The two ends of the fillet fall along the back and though the hair is carefully combed towards the back of the head, no bun is present. The flat back of the head may have held a separately carved bun as is traditional on the other seated figures, or it could have held a more elaborate horn and plumed headdress. Two holes beneath the highly stylized ears suggest that a necklace or other head ornament was attached to the sculpture. The left shoulder is covered with a cloak decorated with trefoil, double circle and single circle designs that were originally filled with red pigment. Drill holes in the center of each circle indicate they were made with a specialized drill and then touched up with a chisel. Eyes are deeply incised and may have held inlay. The upper lip is shaved and a short combed beard frames the face. The large crack in the face is the result of weathering or it may be due to original firing of this object. Priest King : Material: white, low fired steatite Dimensions: 17.5 cm height, 11 cm width Mohenjo-daro, DK 1909 National , Karachi, 50.852 Marshall 1931: 356-7, pl. XCVIII

- 20. Dancing Girl C. 2500 B.C. Place of Origin: Mohenjodaro Materials: Bronze Dimensions: 10.5 x 5 x 2.5 cm. One of the rarest artifacts world-over, a unique blend of antiqueness and art indexing the lifestyle, taste and cultural excellence of a people in such remote past as about five millenniums from now, the tiny bronze-cast, the statue of a young lady now unanimously called 'Indus dancing girl', represents a stylistically poised female figure performing a dance. The forward thrust of the left leg and backwards tilted right, the gesture of the hands, demeanor of the face and uplifted head, all speak of absorption in dance, perhaps one of those early styles that combined drama with dance, and dialogue with body-gestures. As was not unusual in the lifestyle of early days, the young lady has been cast as nude. The statue, recovered in excavation from 'HR area' of Mohenjo-Daro, is suggestive of two major breaks-through, one, that the Indus artists knew metal blending and casting and perhaps other technical aspects of metallurgy, and two, that a well developed society Indus people had innovated dance and other performing arts as modes of entertainment. Large eyes, flat nose, well-fed cheeks, bunched curly hair and broad forehead define the iconography of the lady, while a tall figure with large legs and arms, high neck, subdued belly, moderately sized breasts and sensuously modeled waist-part along vagina, her anatomy. The adornment of her left arm is widely different from the right. While just two, though heavy, rings adorn her right arm, the left is covered in entirety with heavy ringed bangles. Besides, the figure has been cast as wearing on her breasts a necklace with four 'phallis' like shaped pendants. Though a small work of art, it is impressive and surpasses in plasticity and sensuousness the heavily ornate terracotta figurines.

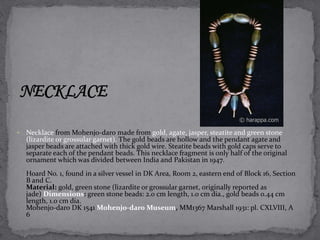

- 21. Necklace from Mohenjo-daro made from gold, agate, jasper, steatite and green stone (lizardite or grossular garnet). The gold beads are hollow and the pendant agate and jasper beads are attached with thick gold wire. Steatite beads with gold caps serve to separate each of the pendant beads. This necklace fragment is only half of the original ornament which was divided between India and Pakistan in 1947. Hoard No. 1, found in a silver vessel in DK Area, Room 2, eastern end of Block 16, Section B and C. Material: gold, green stone (lizardite or grossular garnet, originally reported as jade) Dimensions: green stone beads: 2.0 cm length, 1.0 cm dia., gold beads 0.44 cm length, 1.0 cm dia. Mohenjo-daro DK 1541 Mohenjo-daro Museum, MM1367 Marshall 1931: pl. CXLVIII, A 6

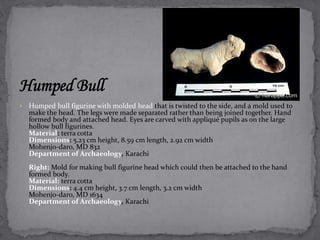

- 22. Humped bull figurine with molded head that is twisted to the side, and a mold used to make the head. The legs were made separated rather than being joined together. Hand formed body and attached head. Eyes are carved with appliqué pupils as on the large hollow bull figurines. Material: terra cotta Dimensions: 5.23 cm height, 8.59 cm length, 2.92 cm width Mohenjo-daro, MD 832 Department of Archaeology, Karachi Right: Mold for making bull figurine head which could then be attached to the hand formed body. Material: terra cotta Dimensions: 4.4 cm height, 3.7 cm length, 3.2 cm width Mohenjo-daro, MD 1634 Department of Archaeology, Karachi

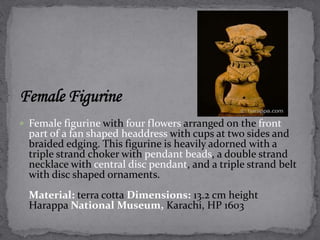

- 23. Female figurine with four flowers arranged on the front part of a fan shaped headdress with cups at two sides and braided edging. This figurine is heavily adorned with a triple strand choker with pendant beads, a double strand necklace with central disc pendant, and a triple strand belt with disc shaped ornaments. Material: terra cotta Dimensions: 13.2 cm height Harappa National Museum, Karachi, HP 1603

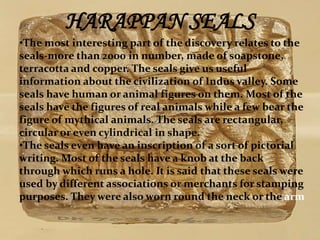

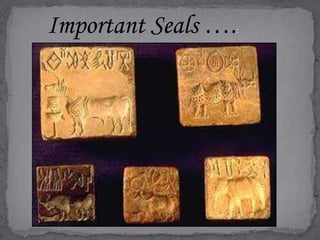

- 24. HARAPPAN SEALS •The most interesting part of the discovery relates to the seals-more than 2000 in number, made of soapstone, terracotta and copper. The seals give us useful information about the civilization of Indus valley. Some seals have human or animal figures on them. Most of the seals have the figures of real animals while a few bear the figure of mythical animals. The seals are rectangular, circular or even cylindrical in shape. •The seals even have an inscription of a sort of pictorial writing. Most of the seals have a knob at the back through which runs a hole. It is said that these seals were used by different associations or merchants for stamping purposes. They were also worn round the neck or the arm

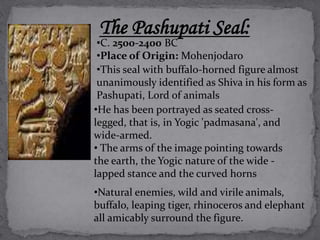

- 26. The Pashupati Seal: •C. 2500-2400 BC •Place of Origin: Mohenjodaro •This seal with buffalo-horned figure almost unanimously identified as Shiva in his form as Pashupati, Lord of animals •He has been portrayed as seated cross-legged, that is, in Yogic 'padmasana', and wide-armed. • The arms of the image pointing towards the earth, the Yogic nature of the wide - lapped stance and the curved horns •Natural enemies, wild and virile animals, buffalo, leaping tiger, rhinoceros and elephant all amicably surround the figure.

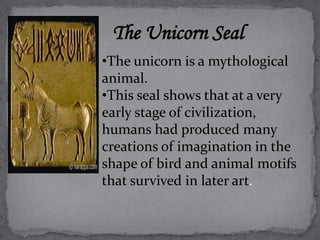

- 27. The Unicorn Seal •The unicorn is a mythological animal. •This seal shows that at a very early stage of civilization, humans had produced many creations of imagination in the shape of bird and animal motifs that survived in later art.

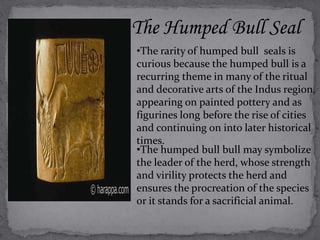

- 28. The Humped Bull Seal •The rarity of humped bull seals is curious because the humped bull is a recurring theme in many of the ritual and decorative arts of the Indus region, appearing on painted pottery and as figurines long before the rise of cities and continuing on into later historical times. •The humped bull bull may symbolize the leader of the herd, whose strength and virility protects the herd and ensures the procreation of the species or it stands for a sacrificial animal.

- 29. The seals show the culture and civilization of the Indus Valley people. In particular, they indicate: • Dresses, ornaments, hair-styles of people. • Skill of artists and sculptors. • Trade contacts and commercial relations. • Religious beliefs. • Script.

- 30. Climate, economic, and social changes all played a role in the process of urbanization and collapse, but these changes affected the human population. When pale climate, archaeology, and human skeletal biology approaches are combined, scientists can glean important insights from the past, addressing long-standing and socially relevant questions. “Early research had proposed that ecological factors were the cause of the demise, but there wasn’t much pale-environmental evidence to confirm those theories. In the past few decades, there have been refinements to the available techniques for reconstructing pale-environments and burgeoning interest in this field,” Dr Schug said.

- 31. “Scientists cannot make assumptions that climate changes will always equate to violence and disease. However, in this case, it appears that the rapid urbanization process in Harappan cities, and the increasingly large amount of culture contact, brought new challenges to the human population. Infectious diseases like leprosy and tuberculosis were probably transmitted across an interaction sphere that spanned Middle and South Asia.” “As the environment changed, the exchange network became increasingly incoherent. When you combine that with social changes and this particular cultural context, it all worked together to create a situation that became untenable,” Dr Schug said. Dr Schug and her colleagues examined evidence for trauma and infectious disease in the human skeletal remains from three burial areas at the city of Harappa. Their findings counter longstanding claims that the Harappan civilization developed as a peaceful, cooperative, and egalitarian state-level society, without social differentiation, hierarchy, or differences in access to basic resources.

- 32. Conclusions The results of the study are striking, because violence and disease increased through time, with the highest rates found as the human population was abandoning the cities. However, an even more interesting result is that individuals who were excluded from the city’s formal cemeteries had the highest rates of violence and disease. In a small ossuary southeast of the city, men, women, and children were interred in a small pit. The rate of violence in this sample was 50 percent for the 10 crania preserved, and more than 20 percent of these individuals demonstrated evidence of infection with leprosy. The results suggest instead that some communities at Harappa faced more significant impacts than others from climate and socio-economic strains, particularly the socially disadvantaged or marginalized communities who are most vulnerable to violence and disease. This pattern is expected in strongly socially differentiated, hierarchical but weakly controlled societies facing resource stress.

- 33. http://www.harappa.com/har/har1.html www.archaeologyonline.net jeyakumar1962.blogspot.com http://asi.nic.in/asi_exca_2007_dholavira.asp www.jstor.org www.panjabdigiib.org http://vedanta-ced.blogspot.in/2010/02/town-planning_ 14.html http://historyinworld.blogspot.in/2011/12/lothal-city-ahmedabad. html http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lothal