3.4 Fallacies Of Presumption Ambiguity And Grammatical Analogy

- 1. 3.4 Fallacies of Presumption, Ambiguity, and Grammatical Analogy

- 2. Overview Fallacies of presumption Fallacies of ambiguity Fallacies of grammatical analogy

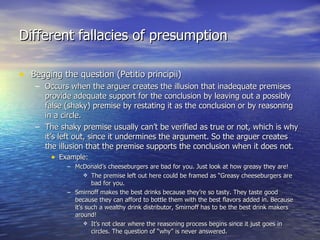

- 3. Different fallacies of presumption Begging the question (Petitio principii) Occurs when the arguer creates the illusion that inadequate premises provide adequate support for the conclusion by leaving out a possibly false (shaky) premise by restating it as the conclusion or by reasoning in a circle. The shaky premise usually can’t be verified as true or not, which is why it’s left out, since it undermines the argument. So the arguer creates the illusion that the premise supports the conclusion when it does not. Example: McDonald’s cheeseburgers are bad for you. Just look at how greasy they are! The premise left out here could be framed as “Greasy cheeseburgers are bad for you. Smirnoff makes the best drinks because they’re so tasty. They taste good because they can afford to bottle them with the best flavors added in. Because it’s such a wealthy drink distributor, Smirnoff has to be the best drink makers around! It’s not clear where the reasoning process begins since it just goes in circles. The question of “why” is never answered.

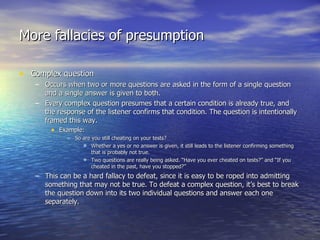

- 4. More fallacies of presumption Complex question Occurs when two or more questions are asked in the form of a single question and a single answer is given to both. Every complex question presumes that a certain condition is already true, and the response of the listener confirms that condition. The question is intentionally framed this way. Example: So are you still cheating on your tests? Whether a yes or no answer is given, it still leads to the listener confirming something that is probably not true. Two questions are really being asked. “Have you ever cheated on tests?” and “If you cheated in the past, have you stopped?” This can be a hard fallacy to defeat, since it is easy to be roped into admitting something that may not be true. To defeat a complex question, it’s best to break the question down into its two individual questions and answer each one separately.

- 5. More fallacies of presumption False dichotomy This one occurs when an arguer offers the listener two alternative answers to a question, as though they were the only possible options. Usually these are poor choices since there is a third one that provides a better answer to the question. Fallacy occurs when the alternatives provided to the listener are false or are probably false. When one of them is true, then no fallacy is committed. Examples: Either you give me $20 or I’ll hate you forever. It’s clear that there are other options beyond being hated and giving up money. Either you eat beef jerky or you’re not a real man. You told me you don’t eat beef jerky, therefore it’s clear you’re not a real man. Judging someone’s manhood can be done in other ways besides eating beef jerky, so it’s clear this is a poor set of choices.

- 6. More fallacies of presumption Suppressed evidence Occurs when an argument leaves out an important fact that is relevant to the premises and how well they support the conclusion. The evidence left out typically would support a different conclusion than the one given. Examples: Your car is as good as new. I mean, look at that paint job! This may sound like a good argument, but what if we consider that the car has an oil leak and hasn’t been serviced in fifteen years? It may look new but that doesn’t mean it will run like new. Evidence like this is important to the conclusion, so it’s clear that it was left out for a reason. You’ve lived on $1000 for the past year, so you won’t have any trouble living off that much for another year or so. What if we learn that the listener is going to have a baby soon? Or is getting ready to buy a new car? This would have a big impact on her finances, and ties in greatly with how well the premises work together with the conclusion.

- 7. Fallacies of ambiguity Equivocation Occurs when a conclusion depends on the fact that a word is used, but it’s used in two different senses within the argument. Examples: Bad people should be put in jail. I’m a bad salesman, therefore I should also be put in jail. The word “bad” is used differently in the premise than it is in the conclusion, so a fallacy is committed here. You told me the crate over there was light, but I can’t see anything inside it. The listener took the word light to mean something that acts as a source of light, and not as something that doesn’t weigh much. Pete said he got stoned last night but I think he’s lying. He doesn’t have any bruises.

- 8. More fallacies of ambiguity Amphiboly The arguer misinterprets an ambiguous statement and draws a conclusion based on that faulty interpretation. Examples: There will be a talk tomorrow over coffee in the cafeteria. It must be the case that coffee has become a popular topic for discussion. It’s not clear whether the talk will be about coffee, or if coffee will be drank while they talk. You told me that I’m looking pretty blue. It follows that I look like a blueberry. There’s two possibilities, that the speaker is depressed or that his skin is turning blue.

- 9. Fallacies of grammatical analogy Composition Occurs when properties of a thing’s parts are improperly transferred over to the whole. Example: Each ingredient in this recipe tastes bad. Therefore, the finished dish will also taste bad. Each atom in this chalkboard is invisible. It follows that the chalkboard is invisible. Division The opposite of composition. Occurs when properties of a class of things are improperly transferred to its individual parts. Example: This pitcher of tea tastes sweet. Therefore, the tea leaves in it must taste sweet. That painting on the wall appears brown. Therefore, all the paint on it must be brown.

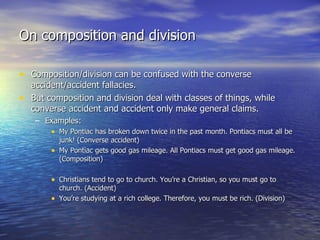

- 10. On composition and division Composition/division can be confused with the converse accident/accident fallacies. But composition and division deal with classes of things, while converse accident and accident only make general claims. Examples: My Pontiac has broken down twice in the past month. Pontiacs must all be junk! (Converse accident) My Pontiac gets good gas mileage. All Pontiacs must get good gas mileage. (Composition) Christians tend to go to church. You’re a Christian, so you must go to church. (Accident) You’re studying at a rich college. Therefore, you must be rich. (Division)