Loading AI tools

Potential candidates for admission into the European Union From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

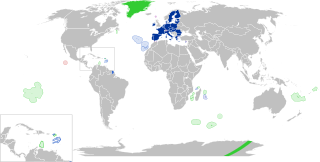

There are currently nine states recognized as candidates for membership of the European Union: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Turkey, and Ukraine.[1] Kosovo (the independence of which is not recognised by five EU member states) formally submitted its application for membership in 2022 and is considered a potential candidate by the European Union. Due to multiple factors, talks with Turkey are at an effective standstill since December 2016.[2]

Six candidates are currently engaged in active negotiations: Montenegro (since 2012), Serbia (since 2014), Albania (since 2020), North Macedonia (since 2020), Moldova and Ukraine (since 2024). The most advanced stage of the negotiations, defined as meeting the interim benchmarks for negotiating chapters 23 and 24, after which the closing process for all chapters can begin, has only been reached by Montenegro.[3] Montenegro's declared political goal is to complete its negotiations by the end of 2026, and achieve membership of the EU by 2028.[4][5]

The accession criteria are included in the Copenhagen criteria, agreed in 1993, and the Treaty of Maastricht (Article 49). Article 49 of the Maastricht Treaty (as amended) says that any European state

that respects the principles of liberty, democracy, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, and the rule of law

, may apply to join the EU. Whether a country is European or not is subject to political assessment by the EU institutions.[6] Past enlargement since the foundation of the European Union as the European Economic Community by the Inner Six states in 1958[7] brought total membership of the EU to twenty-eight, although as a result of the withdrawal of the United Kingdom, the current number of EU member states is twenty-seven.

Of the four major western European countries that are not EU members, Norway, Switzerland and Iceland have submitted membership applications in the past but subsequently frozen or withdrawn them, while the United Kingdom is a former member. Norway, Switzerland, Iceland, as well as Liechtenstein, participate in the EU Single Market and also in the Schengen Area, which makes them closely aligned with the EU; none, however, are in the EU Customs Union.

As of 2025, the enlargement agenda of the European Union regards three distinct groups of states:

These states have all submitted applications for accession to the EU, which is the first step of a long multi-year process. They must subsequently negotiate the specific terms of their Treaty of Accession with the current EU member states, and align their domestic legislation with the accepted body of EU law (acquis communautaire), along with ensuring an appropriate level of implementation thereof, before joining.

There are other potential member states in Europe that are not formally part of the current enlargement agenda, either due to having a domestic political debate on potential membership, or having withdrawn a previous membership or application for membership. These other potential member states could be included on the enlargement agenda at some point of time in the future, if their foreign policy changes and paves the way for submitting an application, and EU subsequently recognises them as an applicant or candidate.

Historically the norm was for enlargements to consist of multiple entrants simultaneously joining the European Economic Community (1958–1993) and EU (since 1993). The only previous enlargements of a single state were the 1981 admission of Greece and the 2013 admission of Croatia. However, following the significant effect of the fifth enlargement in 2004, EU member states have decided that a more individualized approach will be adopted in the future, although the entry of pairs or small groups of countries may coincide.[8]

For an applicant to become a member state of the EU, several procedural steps need to get passed. These steps will move the status of the state from applicant (potential candidate) to candidate, and later again to a negotiating candidate. The status as a negotiating candidate is reached by the mutual signing of a negotiation framework at a first intergovernmental conference. The start of substantial negotiations with the EU, is subsequently marked by the opening of the first negotiating chapters at a second intergovernmental conference. Every 35 chapters of the accepted body of EU law (divided into 6 clusters) must be opened and closed during subsequent additional intergovernmental conferences, for a state to conclude the negotiations by the signing of an accession treaty.

After a reform in 2020, the 35 chapters have been divided into six main clusters, where all five chapters of the first cluster are supposed to be opened together at the same time. The opening of chapters, which after the reform occur with several chapters opened together cluster-wise, can only happen by a unanimous decision by the Council of the European Union once the screening procedure report has been completed for the specific chapters (outlining all needed legislative changes to comply with EU law), while there can also be set some "opening benchmarks" requiring a certain amount of legislative changes/implementation to be met even before the opening of the chapters. The closure of a chapter, is done provisionally by a unanimous decision by the Council of the European Union once the state demonstrates to have implemented and aligned their domestic legislation with the EU law, for each specific chapter in concern.

There are no requirement for completion of the screening procedure for all 35 negotiating chapters, before the start of the first and second intergovernmental conference.[9]

The 2003 European Council summit in Thessaloniki set the integration of the Western Balkans as a priority of EU expansion.

Slovenia was the first former Yugoslav country to join the EU in 2004, followed by Croatia in 2013.

Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia have all been officially granted candidate status.[10][11] Kosovo, which is claimed by Serbia and not recognised by 5 EU states, applied on 14 December 2022 and is considered a potential candidate by the European Union.[12][13]

Serbia and Montenegro, the most advanced candidates in their negotiation processes with the EU, may join the EU sometime between 2025 and 2030.[14][15][16] Montenegro's declared political goal is to complete its negotiations by the end of 2026, and achieve membership of the EU by 2028.[4][5]

The European Council had endorsed starting negotiations with Albania and North Macedonia on 26 March 2020,[17] however, the negotiation process was blocked by Bulgaria for over two years.[18][b] In June 2022 French President Emmanuel Macron submitted a compromise proposal which, if adopted by both countries, would pave the way for the immediate adoption of negotiating frameworks for North Macedonia and Albania by the EU Council and for the organization of intergovernmental conferences with them.[19] On 24 June 2022, Bulgaria's parliament approved the revised French proposal to lift the country's veto on opening EU accession talks with North Macedonia, with the Assembly of North Macedonia also doing so on 16 July 2022 allowing accession negotiations to begin. On the same day, the start of negotiations was set for 19 July 2022.[20]

On 8 November 2023, the European Commission adopted a new Growth Plan for the Western Balkans, with the aim of bringing them closer to the EU through offering some of the benefits of EU membership to the region in advance of accession. The Growth Plan provides €6 billion financial grants and loans for the entire region in return of implementation of structural reforms. Beside the core financial support of the growth plan, one of the additional embedded priority actions is granting access to the Single Euro Payments Area.[21]

On 8 November 2023, the European Commission recommended opening negotiations with Bosnia and Herzegovina once the necessary degree of compliance with the membership criteria is achieved.[22] On 12 March 2024, the European Commission recommended opening EU membership negotiations with Bosnia and Herzegovina, citing the positive results from important reforms the country enacted.[23][24][25] On 21 March 2024, all 27 EU leaders, representing the European Council, gathered for a summit in Brussels, where they unanimously granted conditional approval for opening EU membership negotiations with Bosnia and Herzegovina.[26][27] On 17 December 2024, the Council reiterated that they still needed to receive an approved Growth Plan reform package along with a national programme for adoption of EU law, and that the country should appoint a chief negotiator and a national IPA III coordinator, before the adoption of a negotiation framework can happen as the next step of the process for Bosnia and Herzegovina.[28]

On 25 December 2024, the National Assembly of Republika Srpska (a federal entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina) adopted conclusions alleging the erosion of the legal order in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and demanded the annulment of all acts resulting from unconstitutional actions by foreign individuals (High Representatives) who lack the constitutional authority to propose or enact laws

, and requires representatives from Republika Srpska in state institutions to suspend decisions related to European integration (as well as all decision-making concerned to the overall level of the country) until the process aligns with democratic principles and the rule of law

.[29] However, the High Representative issued an order on 2 January 2025 that prohibited the implementation with immediate legal effect of the entirety of these conclusions, due to having found them to violate Republika Srpska's obligations and commitments under the Dayton Agreement.[30] On 8 January 2025, the President of Republika Srpska, Milorad Dodik, stated that he would seriously reconsider whether Republika Srpska should pursue the European path, as he instead preferred efforts to secede the entity from Bosnia and Herzegovina, and rejected the authority of the Constitutional Court and High Representative.[31] The Delegation of the European Union to Bosnia and Herzegovina stated in response: The sovereignty, territorial integrity, constitutional order – including Constitutional Court decisions – and international personality of Bosnia and Herzegovina need to be respected. The EU urges the political leadership of the Republika Srpska to refrain from and renounce provocative, divisive rhetoric and actions, including questioning the sovereignty, unity and territorial integrity of the country. The EU urges all political actors in BiH to take resolute action to implement the necessary reforms to advance on the EU path towards opening EU accession negotiations. We reiterate our full commitment to the EU accession perspective of BiH as a single, united and sovereign country

.[32]

The Association Trio is sometimes expanded to the Trio + 1 with the inclusion of Armenia, which is not formally on the EU's enlargement agenda but is considering submitting an application for membership.

In 2005, the European Commission suggested in a strategy paper that the present enlargement agenda could potentially block the possibility of a future accession of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine.[33] Olli Rehn, the European Commissioner for Enlargement between 2004 and 2010, said on the occasion that the EU should avoid overstretching our capacity, and instead consolidate our enlargement agenda,

adding, this is already a challenging agenda for our accession process.

[34] In May 2009, the Eastern Partnership was established as a specific dimension of the European Neighbourhood Policy, which contains both a bilateral and multilateral track for six Eastern neighbours to the European Union (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine),[35] in the form of an institutionalised forum for discussing visa agreements, free trade deals, and strategic partnership agreements, while there is no requirement to pursue an accession to the European Union.[36]

The European Parliament passed a resolution in April 2014 stating that in accordance with Article 49 of the Treaty on European Union, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, as well as any other European country, have a European perspective and can apply for EU membership in compliance with the principles of democracy, respect for fundamental freedoms and human rights, minority rights and ensuring the rule of rights.

[37] In 2016-17 Association Agreements between the EU and Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine were ratified, and collectively these three countries became referred to as the Association Trio. They also entered the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area with the EU, which creates framework for modernising [...] trade relations and for economic development by the opening of markets via the progressive removal of customs tariffs and quotas, and by an extensive harmonisation of laws, norms and regulations in various trade-related sectors, creating the conditions for aligning key sectors

of their economies with EU standards.[38] However, the EU did not expand further into the post-Soviet space in the 2010s.[39]

By January 2021, Georgia and Ukraine were preparing to formally apply for EU membership in 2024.[40][41][42] However, following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Ukraine submitted an application for EU membership on 28 February 2022, followed by Georgia and Moldova on 3 March 2022.[43][44] On 23 June 2022, the European Council granted candidate status to Moldova and Ukraine, and recognized Georgia as a potential candidate for membership.[45] When taking its candidacy decision for Ukraine and Moldova, the Council made opening the accession negotiations conditional to addressing respectively seven and nine key areas related to strengthening the rule of law, fighting corruption and improving governance processes.

In his speech in Moldova on 28 March 2023, President of the European Council Charles Michel mentioned that by the end of the year, the Council will have to decide on the opening negotiations with [Ukraine and Moldova]. It will be a political decision taking into account the report that will be published by the Commission. And I sincerely hope that a positive decision will be possible by the end of the year

.[46]

On 8 November 2023, the European Commission recommended opening negotiations with Moldova and Ukraine, and granting candidate status to Georgia,[22] and this was agreed by the European Council on 14 December 2023.[47]

On 25 June 2024, the first Intergovernmental Conference (IGC) was called by the Belgian Presidency of the Council of the EU, officially marking the start of the accession negotiations with Moldova and Ukraine.[48]

On 9 July 2024, following the adoption of a law by Georgia's ruling Georgian Dream party requiring non-governmental and media entities to register as "foreign agents", the EU ambassador in Georgia announced that in response the EU would de facto halt the country's accession progress, with no further steps to advance the process to be expected and no financial support granted for as long as the law exists.[49][50] The European Union has threatened Georgia with sanctions and suspension of relations if the country becomes a "one-party state" without political opposition following parliamentary elections in October 2024.[51]

The 2024 Georgian parliamentary elections resulted in Georgian Dream retaining power, but were disputed by opposition parties which claimed that the vote was not free and fair and was subject to widespread voter fraud. The European Parliament adopted a non-binding resolution which rejected the validity of the results, and called for the vote to be repeated within a year.[52] Following this, Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze stated that accession negotiations would be suspended until the end of 2028,[53] though he insisted that his government would continue to implement the reforms required for accession and that it still planned for Georgia to join the EU by 2030.[54]

The EU have halted all financial aid for the Georgian government since 27 June 2024, and instead redirected its financial support only to be received by civil society and the media in Georgia.[50] Similair to the growth plans and IPA III grants launched towards supporting strucutural reforms to improve accession perspectives for candidates from the Western Balkans, the EU launched – or is about to launch – similair growth plan programmes for Ukraine and Moldova:[28]

In October 2024, the Moldovan EU membership referendum resulted in support to amend the Constitution of Moldova to include the aim of becoming an EU member state.[61][62][63]

Turkey's candidacy to join the EU has been a matter of major significance and considerable controversy since it was granted in 1999. Turkey has had historically close ties with the EU, having an association agreement since 1964,[64] being in a customs union with the EU since 1995 and initially applying to join in 1987. Only after a summit in Brussels on 17 December 2004 (following the major 2004 enlargement) did the European Council announce that membership negotiations with Turkey were officially opened on 3 October 2005.

Turkey is the eleventh largest economy in the world (measured as Purchasing Power Parity), and is a key regional power.[65][66] In 2006, Carl Bildt, former Swedish foreign minister, stated that [The accession of Turkey] would give the EU a decisive role for stability in the Eastern part of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, which is clearly in the strategic interest of Europe.

[67] However, others, such as former French President Nicolas Sarkozy and former German Chancellor Angela Merkel, expressed opposition to Turkey's membership. Opponents argue that Turkey does not respect the key principles that are expected in a liberal democracy, such as the freedom of expression.[68]

Turkey's large population would also alter the balance of power in the representative European institutions. Upon joining the EU, Turkey's 84 million inhabitants would bestow it the largest number of MEPs in the European Parliament. It would become the most populous country in the EU.[69] Another problem is that Turkey does not recognise one EU member state, Cyprus, because of the Cyprus problem and the Cypriot government blocks some chapters of Turkey's talks.[70][71]

EU–Turkey relations have deteriorated following President Erdoğan's crackdown on supporters of the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt. While Erdoğan stated that he approved the reintroduction of the death penalty to punish those involved in the coup, the EU announced that it strongly condemned the coup attempt and would officially end accession negotiations with Turkey if the death penalty was reintroduced.[72] On 25 July 2016, President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker said that Turkey was not in a position to become a member of the European Union in the near future and that accession negotiations between the EU and Turkey would be stopped immediately if the death penalty was brought back.[73] On 24 November 2016, the European Parliament approved a non-binding resolution calling for the temporary freeze of the ongoing accession negotiations with Turkey

over human rights and rule of law concerns.[74][75][76] On 13 December 2016, the European Council (comprising the heads of state or government of the member states) resolved that it would open no new areas in Turkey's membership talks in the "prevailing circumstances",[77] as Turkey's path toward autocratic rule made progress on EU accession impossible.[78] On 6 July 2017, the European Parliament accepted the call for the suspension of full membership negotiations between the EU and Turkey,[79] and a repeat of the exact same vote ended with the same result in March 2019[80] and May 2021.[81] On 17 July 2018, then-Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz said that it would be beneficial to end the accession negotiations between the EU and Turkey and instead develop bilateral relations between the EU and Turkey.[82] As of 2022, and especially following Erdoğan's victory in the constitutional referendum, Turkish accession talks are effectively at a standstill.[2][83][84]

In July 2023, Erdoğan brought up Turkey's accession to EU membership up in the context of Sweden's application for NATO membership.[85] However, in September 2023, he announced that the European Union was well into a rupture in its relations with Turkey and that they could part ways during Turkey's European Union membership process.[86]

| State | Status[87] | Chapters opened |

Chapters closed |

Latest steps | Next step | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(accession process) |

Candidate negotiating (since June 2012)[88] |

33/33[88]

|

6/33[88]

|

Screening completed for all chapters in June 2013.[89] First chapters opened in December 2012.[90] | Every chapter must be closed to conclude the negotiations. | ||||||||

(accession process) |

Candidate negotiating (since January 2014)[91] |

22/34[91]

|

2/34[91]

|

Screening completed for all chapters in March 2015.[92] First chapters opened in December 2015.[93] | Every chapter must be opened and closed to conclude the negotiations. Benchmarks have been met for the opening of all 3 remaining chapters in cluster 3, but this has been postponed due the opening being conditional on "substantial further progress made by Serbia, in particular in accordance with...the rule of law (chapter 23+24) and the normalisation of relations with Kosovo".[28][94] | ||||||||

(accession process) |

Candidate negotiating (since July 2022)[95] |

7/33[96]

|

0/33[96]

|

Screening completed for all chapters in November 2023.[97] First chapters opened in October 2024.[98] | Every chapter must be opened and closed to conclude the negotiations. | ||||||||

(accession process) |

Candidate negotiating (since July 2022)[95] |

0/33[99]

|

0/33[99]

|

Screening completed for all chapters in December 2023.[99] | The opening of the first 5 negotiating chapters (Fundamentals cluster) at a second intergovernmental conference will not begin until the opening phase has been completed, which according to the Council conclusions of July 2022 is conditional on the Assembly of North Macedonia approving a constitutional amendment related to the Bulgarian minority.[100][101][28] | ||||||||

(accession process) (relations) |

Candidate negotiating (since June 2024)[48][102] |

0/33[103]

|

0/33[103]

|

Screening of chapters (the explanatory phase) began in January 2024,[9] and the bilateral phase of the screening started in July 2024.[104] | The opening of the first 5 negotiating chapters (Fundamentals cluster) at a second intergovernmental conference. Every chapter must be opened and closed to conclude the negotiations. | ||||||||

(accession process) (relations) |

Candidate negotiating (since June 2024)[48][105] |

0/33[106]

|

0/33[106]

|

Screening of chapters (the explanatory phase) began in January 2024,[9] and the bilateral phase of the screening started in July 2024.[107] | The opening of the first 5 negotiating chapters (Fundamentals cluster) at a second intergovernmental conference. Every chapter must be opened and closed to conclude the negotiations. | ||||||||

(accession process) |

Candidate (since December 2022)[108] |

— | — | The European Council granted conditional approval for the opening of accession negotiations in March 2024.[109][108] Screening of chapters (the explanatory phase) began in April 2024.[110] | The European Commission needs to prepare a negotiating framework for adoption by the Council, once all relevant steps set out in the Commission's recommendation of 12 October 2022 have been taken by Bosnia and Herzegovina.[111] The state claimed to meet 98% of conditions demanded by the European Commission by passing a 2024 budget and Growth Plan reform package in July 2024.[112][113][114] Final approval of the Growth Plan reform package was however blocked by four cantons on 25 July.[115] As of December 2024, the Council reminded they still needed to receive an approved Growth Plan reform package along with a national programme for adoption of EU law, and that the country should appoint a chief negotiator and a national IPA III coordinator, before the adoption of a negotiation framework can happen as the next step of the process.[28] | ||||||||

(accession process) (relations) |

Candidate (since December 2023)[47] |

— | — | The European Council granted candidate status in December 2023.[116] The Georgian government suspended its EU membership application process until the end of 2028.[53][28] | The European Commission needs to recommend starting negotiations. | ||||||||

(accession process) |

Applicant / Potential candidate | — | — | Application for membership submitted in December 2022.[13] | The Council needs to by unanimous decision request the European Commission to submit an opinion. | ||||||||

(accession process) (relations) |

Candidate with frozen negotiations (opened in October 2005,[117] but frozen since December 2016)[77] |

16/33[118]

|

1/33[118]

|

Screening completed for all chapters in October 2006.[117] First chapters opened in June 2006.[117] Chapter opening frozen in December 2016, due to backsliding in the areas of democracy, rule of law, and fundamental rights.[77] Chapter closing dialogue frozen since June 2018.[119][118] | Negotiations frozen, with no further chapters being considered for opening or closing, which has been reconfirmed by the Council each year since 2018.[118][119][120][121][122][101][28] |

| Major events | Association Agreement (with link) |

Membership application |

Candidate status |

Negotiations start (1st IGC) |

Substantial negotiations start (2nd IGC) |

Accession Treaty signed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Dec 1964 (AA) | 14 Apr 1987 | 12 Dec 1999 | 3 Oct 2005[123] | 12 Jun 2006[117][124] | (tbd) | |

| 1 May 2010 (SAA) | 15 Dec 2008 | 17 Dec 2010[125] | 29 Jun 2012[88] | 18 Dec 2012[90] | (tbd) | |

| 1 Sep 2013 (SAA) | 22 Dec 2009 | 1 Mar 2012 | 21 Jan 2014[126] | 14 Dec 2015[93] | (tbd) | |

| 1 Apr 2009 (SAA) | 28 Apr 2009 | 27 Jun 2014[127][128] | 19 Jul 2022[95] | 15 Oct 2024[98] | (tbd) | |

| 1 Apr 2004 (SAA) | 22 Mar 2004 | 17 Dec 2005 | 19 Jul 2022[95] | (tbd) | (tbd) | |

| 1 Jul 2016 (AA) | 3 Mar 2022[129] | 23 Jun 2022[45] | 25 Jun 2024[130] | (tbd) | (tbd) | |

| 1 Sep 2017 (AA) | 28 Feb 2022[131] | 23 Jun 2022[45] | 25 Jun 2024[132] | (tbd) | (tbd) | |

| 1 Jun 2015 (SAA)[133] | 15 Feb 2016[134] | 15 Dec 2022[11] | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | |

| 1 Jul 2016 (AA) | 3 Mar 2022[135] | 14 Dec 2023[47] | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | |

| 1 Apr 2016 (SAA)[136] | 14 Dec 2022[13] | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) |

| All events | Candidates negotiating | Candidates | Applicant / Potential candidate |

Candidate with frozen negotiations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | Moldova | Montenegro | North Macedonia | Serbia | Ukraine | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Georgia | Kosovo[Note 1] | Turkey | ||||

| EU Association Agreement[Note 2] | |||||||||||||

| EU Association Agreement negotiations start | 31 Jan 2003 | Jan 2010[137] | 10 Oct 2005[Note 3] | 5 Apr 2000 | 10 Oct 2005[Note 4] | 5 Mar 2007 | 25 Nov 2005 | Jan 2010 | 28 Oct 2013[139] | 1959AA 1970CU | |||

| EU Association Agreement signature | 12 Jun 2006 | 27 Jun 2014 | 15 Oct 2007 | 9 Apr 2001 | 29 Apr 2008 | 21 Mar 2014AA 27 Jun 2014DCFTA |

16 Jun 2008 | 27 Jun 2014 | 27 Oct 2015[140] | 12 Sep 1963AA 1995CU | |||

| EU Association Agreement entry into force | 1 Apr 2009 | 1 Jul 2016 | 1 May 2010 | 1 Apr 2004 | 1 Sep 2013 | 1 Sep 2017 | 1 Jun 2015[133] | 1 Jul 2016 | 1 Apr 2016[136] | 1 Dec 1964AA 31 Dec 1995CU[141] | |||

| Membership application | |||||||||||||

| Membership application submitted | 28 Apr 2009 | 3 Mar 2022[129] | 15 Dec 2008 | 22 Mar 2004 | 22 Dec 2009 | 28 Feb 2022[131] | 15 Feb 2016[134] | 3 Mar 2022[135] | 14 Dec 2022[13] | 14 Apr 1987 | |||

| Council asks Commission for opinion | 16 Nov 2009 | 7 Mar 2022[142] | 23 Apr 2009 | 17 May 2004 | 25 Oct 2010[143] | 7 Mar 2022[142] | 20 Sep 2016[144] | 7 Mar 2022[142] | (tbd) | 27 Apr 1987 | |||

| Commission presents legislative questionnaire to applicant | 16 Dec 2009 | 11 Apr 2022 (Part I) 19 Apr 2022 (Part II)[145] |

22 Jul 2009 | 1 Oct 2004 | 24 Nov 2010 | 8 Apr 2022 (Part I) 13 Apr 2022 (Part II)[146] |

9 Dec 2016[147] | 11 Apr 2022 (Part I) 19 Apr 2022 (Part II)[145][148] |

(tbd) | ||||

| Applicant responds to questionnaire | 11 Jun 2010 | 22 Apr 2022 (Part I)[149] 12 May 2022 (Part II)[150] |

12 Apr 2010 | 10 May 2005 | 22 Apr 2011 | 17 Apr 2022 (Part I)[151] 9 May 2022 (Part II)[152] |

28 Feb 2018 | 2 May 2022 (Part I)[153] 10 May 2022 (Part II)[154] |

(tbd) | ||||

| Commission issues its opinion (and subsequent reports) | 2010–2013 | 17 Jun 2022[155] | 9 Nov 2010 | 2005–2009 | 12 Oct 2011 | 17 Jun 2022[155] | 2019[156]–2022 | 17 Jun 2022[155] | (tbd) | 1989, 1997–2004 | |||

| Candidate status | |||||||||||||

| Commission recommends granting of candidate status | 16 Oct 2013[157] | 17 Jun 2022[155] | 9 Nov 2010 | 9 Nov 2005 | 12 Oct 2011 | 17 Jun 2022[155] | 12 Oct 2022[158] | 8 Nov 2023[22] | (tbd) | 13 Oct 1999 | |||

| European Council grants candidate status to Applicant | 27 Jun 2014[127][128] | 23 Jun 2022[45] | 17 Dec 2010[125] | 17 Dec 2005 | 1 Mar 2012 | 23 Jun 2022[45] | 15 Dec 2022[11] | 14 Dec 2023[47] | (tbd) | 12 Dec 1999 | |||

| Accession negotiations | |||||||||||||

| Commission recommends to open negotiations | 9 Nov 2016[159] | 8 Nov 2023[22] | 12 Oct 2011 | 14 Oct 2009 | 22 Apr 2013[160] | 8 Nov 2023[22] | 12 Mar 2024[24] | (tbd) | (tbd) | 6 Oct 2004 | |||

| European Council decides to open negotiations | 26 Jun 2018[161][162][163] | 14 Dec 2023[164] | 28 Jun 2012[88] | 18 Jun 2019[163] | 28 Jun 2013[165] | 14 Dec 2023[164] | 21 Mar 2024[111] | (tbd) | (tbd) | 16 Dec 2004[166] | |||

| Council sets negotiations start date | 24 Mar 2020[167] | 21 Jun 2024[168] | 26 Jun 2012[169] | 24 Mar 2020[167] | 17 Dec 2013[170] | 21 Jun 2024[168] | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | 17 Dec 2004 | |||

| Membership negotiations start (first IGC) | 19 Jul 2022[95] | 25 Jun 2024[130] | 29 Jun 2012[88] | 19 Jul 2022[95] | 21 Jan 2014[126] | 25 Jun 2024[132] | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | 3 Oct 2005[123] | |||

| First negotiating chapters opened (second IGC) | 15 Oct 2024[98] | (tbd) | 18 Dec 2012[90] | (tbd) | 14 Dec 2015[93] | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | 12 Jun 2006[117][124] | |||

| Membership negotiations end | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | |||

| Accession treaty and joining the EU | |||||||||||||

| Accession Treaty signature | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | |||

| EU joining date | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | (tbd) | |||

| |||||||||||||

The table below shows the level of preparation of applicant countries with EU standards (acquis communautaire) on a 5-point scale, using data from the European Commission's 2024 reports. The analysis is based on the analysis performed by the online media outlet European Pravda for Ukraine; scores for other countries, as well as additional sections (public administration reform and economic criteria) were added based on official data from the European Commission's reports.[171][172]

| Chapter | Candidates negotiating | Candidates | Applicant / Potential candidate |

Candidate with frozen negotiations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | Moldova | Montenegro | North Macedonia | Serbia | Ukraine | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Georgia | Kosovo | Turkey | ||||

| Cluster 1: The fundamentals of the accession process | |||||||||||||

| Public administration reform | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1.5 | 3 | 2 | 2.5 | |||

| 23. Judiciary and fundamental rights | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2.5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.5 | 1 | |||

| 24. Justice, freedom and security | 3 | 2 | 3.5 | 3 | 2.5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | |||

| The existence of a functioning market economy | 4 | 1.5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1.5 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | |||

| The capacity to cope with competitive pressure and market forces within the Union | 2 | 1.5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |||

| 5. Public procurement | 3 | 2 | 3.5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | |||

| 18. Statistics | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 32. Financial control | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Cluster 2: Internal Market | |||||||||||||

| 1. Free movement of goods | 2.5 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2.5 | 4 | |||

| 2. Freedom of movement for workers | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 3. Right of establishment and freedom to provide services | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | |||

| 4. Free movement of capital | 3 | 2.5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2.5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||

| 6. Company law | 3 | 1.5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |||

| 7. Intellectual property law | 3 | 2 | 4.5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 8. Competition policy | 2.5 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1.5 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 9. Financial services | 3.5 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2.5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 28. Consumer and health protection | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Cluster 3: Competitiveness and inclusive growth | |||||||||||||

| 10. Digital transformation and media | 3.5 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3.5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 16. Taxation | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3.5 | 2 | 2 | 2.5 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 17. Economic and monetary policy | 3.5 | 2 | 3 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | |||

| 19. Social policy and employment | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1.5 | 2 | |||

| 20. Enterprise and industrial policy | 3.5 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 | 3 | 2.5 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||

| 25. Science and research | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 5 | |||

| 26. Education and culture | 3 | 2.5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 29. Customs union | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Cluster 4: The Green agenda and sustainable connectivity | |||||||||||||

| 14. Transport | 2 | 2 | 3.5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||

| 15. Energy | 3.5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 21. Trans-European networks | 2 | 2 | 3.5 | 4 | 3.5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |||

| 27. Environment and climate change | 2 | 1.5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Cluster 5: Resources, agriculture and cohesion | |||||||||||||

| 11. Agriculture and rural development | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 12. Food safety, veterinary and phytosanitary policy | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2.5 | 2 | |||

| 13. Fisheries and aquaculture | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||

| 22. Regional policy and coordination of structural instruments | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 3 | |||

| 33. Financial and budgetary provisions | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 2 | |||

| Cluster 6: External relations | |||||||||||||

| 30. External relations | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |||

| 31. Foreign, security and defence policy | 4 | 3.5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | — | 2 | |||

| Average level | 2.82 | 1.99 | 3.18 | 3.06 | 3.13 | 2.22 | 1.64 | 2.18 | 1.99 | 2.99 | |||

|

5 Well advanced

4.5 Good / Well advanced

4 Good level of preparation

3.5 Moderate / Good

3 Moderately prepared

2.5 Some / Moderate

2 Some level of preparation

1.5 Early stage / Some

1 Early stage | |||||||||||||

The table below shows the progress over the past year of applicant countries on a 4-point scale, using data from the European Commission's 2024 reports. The analysis is based on the analysis performed by the online media outlet European Pravda for Ukraine; scores for other countries, as well as additional sections (public administration reform and economic criteria) were added based on official data from the European Commission's reports.[173][174]

| Chapter | Candidates negotiating | Candidates | Applicant / Potential candidate |

Candidate with frozen negotiations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | Moldova | Montenegro | North Macedonia | Serbia | Ukraine | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Georgia | Kosovo | Turkey | ||||

| Cluster 1: The fundamentals of the accession process | |||||||||||||

| Public administration reform | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 23. Judiciary and fundamental rights | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | -4 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 24. Justice, freedom and security | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| The existence of a functioning market economy | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | |||

| The capacity to cope with competitive pressure and market forces within the Union | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 5. Public procurement | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 18. Statistics | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 32. Financial control | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Cluster 2: Internal Market | |||||||||||||

| 1. Free movement of goods | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 2. Freedom of movement for workers | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 3. Right of establishment and freedom to provide services | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 4. Free movement of capital | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 6. Company law | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |||

| 7. Intellectual property law | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |||

| 8. Competition policy | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 9. Financial services | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 28. Consumer and health protection | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Cluster 3: Competitiveness and inclusive growth | |||||||||||||

| 10. Digital transformation and media | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 16. Taxation | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |||

| 17. Economic and monetary policy | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 19. Social policy and employment | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | |||

| 20. Enterprise and industrial policy | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 25. Science and research | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 26. Education and culture | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 29. Customs union | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | |||

| Cluster 4: The Green agenda and sustainable connectivity | |||||||||||||

| 14. Transport | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 15. Energy | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 21. Trans-European networks | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 27. Environment and climate change | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Cluster 5: Resources, agriculture and cohesion | |||||||||||||

| 11. Agriculture and rural development | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 12. Food safety, veterinary and phytosanitary policy | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |||

| 13. Fisheries and aquaculture | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |||

| 22. Regional policy and coordination of structural instruments | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 33. Financial and budgetary provisions | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | |||

| Cluster 6: External relations | |||||||||||||

| 30. External relations | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 31. Foreign, security and defence policy | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | — | 0 | |||

| Average progress | 1.56 | 1.89 | 1.83 | 1.39 | 1.08 | 1.78 | 0.61 | 1.06 | 1.50 | 1.08 | |||

|

4 Very good progress

3 Good progress

2.5 Some / Good progress

2 Some progress

1 Limited progress

0 No progress

-4 Backsliding | |||||||||||||

The Maastricht Treaty (Article 49) states that any European country (as defined by a European Council assessment) that is committed to democracy may apply for membership in the European Union.[175] In addition to European states, other countries have also been speculated or proposed as future members of the EU.

States in Europe that have chosen, for various reasons, not to join the EU have integrated with it to different extents according to their circumstances. Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein participate directly in the single market via the EEA, Switzerland does so via bilateral treaties and the other European microstates (Andorra, Monaco, San Marino, Vatican City) have specific agreements with the EU and neighbouring countries, including their use of the euro as their currency. Most of these countries are also part of the Schengen Area. Norway, Iceland, and Switzerland have all previously had live applications to join the EU, which have been withdrawn or otherwise frozen. Such applications could be resubmitted in the event of a change in the political landscape.

On 5 March 2024, Armenian prime minister Nikol Pashinyan said that his country would apply for EU candidacy by autumn 2024 at the latest.[179] On 12 March 2024, the European Parliament passed a resolution confirming Armenia met Maastricht Treaty Article 49 requirements and that the country may apply for EU membership.[216] At the 2024 Copenhagen Democracy Summit, Pashinyan stated that if possible he would like Armenia to become a member of the European Union this year

.[217] A petition calling for a referendum on whether Armenia should apply for membership of the EU,[218] which was supported by Pashinyan,[219] succeeded in reaching the 50,000 signatures required in order to be submitted for a vote in the National Assembly.[220][221] The National Assembly is expected to vote on the matter in January 2025.[222] Prior to the vote,[223] the Armenian government expressed a positive position for supporting the bill's approval, with Pashinyan further elaborating that if the bill was approved, then a roadmap should be agreed to with the European Union prior to holding the referendum.[224] The decision for the government to support the bill was reported to be the first step of "the beginning of the accession process of the Republic of Armenia to the European Union".[225][226]

Iceland had active accession negotiations from July 2010 until September 2013, but then the membership application was at first suspended and then withdrawn by the Icelandic government. Since March 2022, opinion polls however showed a stable support for Iceland to join the EU. There was a renewed call in September 2022 for a referendum on resuming EU membership negotiations.[227] Following the 2024 Icelandic parliamentary election, the Social Democratic Alliance, Viðreisn and People's Party formed a new coalition government, which agreed to hold a referendum on resuming negotiations on EU membership by 2027.[228]

Internal enlargement is the process of new member states arising from the break-up of an existing member state.[231][232][233] There have been and are a number of active separatist movements within member states (for example in Catalonia and Flanders) but there are no clear agreements, treaties or precedents covering the scenario of an existing EU member state breaking into two or more states, both of which wish to remain EU member states. The question is whether one state is a successor and one a new applicant or, alternatively, both are new states which must be admitted to the EU.[234][235]

In some cases, a region desires to leave its state and the EU, namely those regions wishing to join Switzerland. But most, namely the two movements that held referendums during the 2010s, Scotland and Catalonia, see their future as independent states within the EU. This results in great interest in whether, once independent, they would retain EU membership or conversely whether they would have to re-apply. In the later case, since new members must be approved unanimously, any other state which has an interest in blocking their membership to deter similar independence movements could do so.[236][237] Additionally, it is unclear whether the successor state would retain any opt-outs that the parent state was entitled to.

If there were to be a 'yes' vote in favour of Catalan independence, then we will respect that opinion. But Catalonia will not be able to be an EU member state on the day after such a vote.[238] This was repeated in October in an official press release:

We [...] reiterate the legal position held by this Commission as well as by its predecessors. If a referendum were to be organised in line with the Spanish Constitution it would mean that the territory leaving would find itself outside of the European Union.[239]

The presence of a strong Basque Nationalist movement, strongly majoritary in several territories of the Basque Country, makes possible the future existence of an independent Basque Country under different potential territorial configurations. In overall terms the Basque nationalism is pro-European.

On 1 October 2017, the Catalan government held a referendum on independence, which had been declared illegal by the Constitutional Court of Spain, with potential polling stations being cordoned off by riot police. The subsequent events constituted a political crisis for Catalonia. The EU's position is to keep distance from the crisis while supporting Spain's territorial integrity and constitution.[247][248] While the debate around Scotland's referendum may inform the Catalan crisis, Catalonia is in a distinct situation from Scotland whereby the central government does not recognise the legitimacy of any independence declaration from Catalonia. If Spain does not recognise the independence of a Catalan state, Catalonia cannot separately join the EU and it is still recognised as part of Spain's EU membership.

Corsica has a strong and electorally successful nationalist movement, with positions ranging from autonomy to outright independence, the latter option with around 10–15% public support.[249] The independist party Corsica Libera envisions an independent Corsica within the European Union as a union of various European peoples, as well as recommendations for alignment within European directives.[250]

There is an active movement towards Flemish independence or union with the Netherlands. The future status of Wallonia and Brussels (the de facto capital of the EU) are unclear as viable political states, perhaps producing a unique situation from Scotland and Catalonia. There are various proposals, both within and outside the independentist movement, for what should happen to Brussels, ranging from staying part of the Belgian rump state, to joining the hypothetical Flemish state, to becoming a separate political entity.[251][252]

Sardinia has a strong and electorally successful nationalist movement, with positions ranging from autonomy to outright independence. Generally associated with left-wing politics, the Sardinian movement is largely pro-European and pro-environmentalism.[253][254]

According to a 2012 survey conducted in a joint effort between the University of Cagliari and that of Edinburgh,[255][256][257] 41% of Sardinians would be in favour of independence (with 10% choosing it from both Italy and the European Union, and 31% only from Italy with Sardinia remaining in the EU), whilst another 46% would rather have a larger autonomy within Italy and the EU, including fiscal power; 12% of people would be content to remain part of Italy and the EU with a Regional Council without any fiscal powers, and 1% in Italy and the EU without a Regional Council and fiscal powers.[258][259][260][261][262][263][264] A 2017 poll by the Ixè Institute found that 51% of those questioned identified as Sardinian (as opposed to an Italian average of 15% identifying by their region of origin), rather than Italian (19%), European (11%) and/or citizen of the world (19%).[265][266]

Sardinian nationalists address a number of issues, such as the environmental damage caused by the military forces[267][268][269][270][271][272][273][274][275] (about 60% of such bases in Italy are located on the island),[276] the financial and economic exploitation of the island's resources by the Italian state and mainland industrialists,[277] the lack of any political representation both in Italy and in the European Parliament[278][279] (due to an unbalanced electoral constituency that still remains to this day,[280] Sardinia has not had its own MEP since 1994),[281] the nuclear power and waste (on which a referendum was proposed by a Sardist party,[282] being held in 2011[283]) and the ongoing process of depopulation and Italianization that would destroy the Sardinian indigenous culture.[284]

Similarly to Sardinia, Veneto has a strong and electorally successful nationalist movement, with positions ranging from autonomy to outright independence. In a controversial online poll held in 2014, 89% of participants were in favour of Veneto becoming "a federal, independent and sovereign state" and 55% supported accession to European Union membership.[285] Three years later, in the 2017 autonomy referendum, with a 58% turnout, 98% of the participants voted in favour of "further forms and special conditions of autonomy to be attributed to the Region of Veneto".[286] Consequently, negotiations between the Venetian government and the Italian one started.

The longstanding and largest Venetist party, Liga Veneta (LV), was established in 1979 under the slogan "farther from Rome, closer to Europe",[287] but has later adopted more Eurosceptic positions. Luca Zaia, a LV member who has served as president of Veneto since 2010, usually self-describes as a pro-Europeanist and has long advocated for a "Europe of regions" and "macro-regions".[288][289][290][291]

This scenario consists of the event of an EU member state taking over a land area outside the union, previously independent or part of a different country. One such event has taken place in history, when East Germany became part of a united Germany in 1991.

Officially, the island nation of Cyprus is part of the European Union, under the de jure sovereignty of the Republic of Cyprus. Turkish Cypriots are citizens of the Republic of Cyprus and thus of the European Union, and were entitled to vote in the 2004 European Parliament election (though only a few hundred registered). The EU's acquis communautaire is suspended indefinitely in the northern third of the island, which has remained outside the control of the Republic of Cyprus since the Turkish invasion of 1974. The Greek Cypriot community rejected the Annan Plan for the settlement of the Cyprus dispute in a referendum on 24 April 2004. Had the referendum been in favour of the settlement proposal, the island (excluding the British Sovereign Base Areas) would have joined the European Union as the United Cyprus Republic. The European Union's relations with the Turkish Cypriot Community are handled by the European Commission's Directorate-General for Enlargement.[292]

The European Council has recognised that following the UK withdrawal from the EU, if Northern Ireland were to be incorporated into a united Ireland it would automatically rejoin the EU under the current Irish membership. A historical precedent for this was the incorporation of East Germany into the Federal Republic of Germany as a single European Communities member state.[293][294]

Opinion polls in both Moldova and Romania show significant support for the unification of the two countries, based on their reciprocal historical and cultural ties.[295][296] Such a scenario would result in Moldova becoming part of an enlarged Romania and therefore receiving the benefits and obligations of the latter's EU membership.[297] An obstacle would be the existence of the breakaway Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (Transnistria), which is considered by Moldova and most of the international community to be de jure part of Moldova's sovereign territory but is de facto independent. Transnistria's absence of strong historical or cultural links to Romania and its close political and military relationship with Russia have been seen as major hurdles to integration of the region with both Romania and the EU.[296] Another likely barrier from within Moldova would be opposition on the part of the autonomous territory of Gagauzia, whose population has been mostly against integration with Romania since at least the 1990s.[298] A 2014 referendum held by the Gagauzian government showed both overwhelming support for the region joining the Customs Union of the Eurasian Economic Union and a similar level of rejection to closer ties with the EU.[299]

There are multiple special member state territories, some of which are not fully covered by the EU treaties and apply EU law only partially, if at all. It is possible for a dependency to change its status regarding the EU or some particular treaty or law provision. The territory may change its status from participation to leaving or from being outside to joining.

The Faroe Islands, a self-governing nation within the Kingdom of Denmark, is not part of the EU, as explicitly asserted by both Rome treaties.[300] The relations with the EU are governed by a Fisheries Agreement (1977) and a Free Trade Agreement (1991, revised 1998). The main reason for remaining outside the EU is disagreements about the Common Fisheries Policy,[301] which disfavours countries with large fish resources. Also, every member has to pay for the Common Agricultural Policy, which favours countries having much agriculture which the Faroe Islands does not. When Iceland was in membership negotiations around 2010, there was a hope of better conditions for fish-rich countries[citation needed], but to no avail. The Common Fisheries Policy was introduced in 1970 for the very reason of getting access for the first EC members to waters of candidate countries, namely the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Denmark including the Faroe Islands.[citation needed]

Nevertheless, there are politicians, mainly in the right-wing Union Party (Sambandsflokkurin), led by their chairman Kaj Leo Johannesen, who would like to see the Faroes as a member of the EU. However, the chairman of the left-wing Republic (Tjóðveldi), Høgni Hoydal, has expressed concerns that if the Faroes were to join the EU as is, they might vanish inside the EU, comparing this with the situation of the Shetland Islands and Åland today, and wants the local government to solve the political situation between the Faroes and Denmark first.[302]

Greenland is part of the Kingdom of Denmark, and became part of the EEC (the predecessor entity of the EU) when Denmark joined in 1973. After the establishment of Greenland's home rule in 1979, which made it an autonomous community, Greenland held a referendum on EEC membership. The result was (mainly because of the Common Fisheries Policy) to leave, so on 1 February 1985, Greenland left the EEC and EURATOM. Its status was changed to that of an Overseas Country.[303][304] Danish nationals residing in Greenland (i.e. all native population) are nonetheless fully European citizens; they are not, however, entitled to vote in European elections.

There has been some speculation as to whether Greenland may consider rejoining the now-European Union. On 4 January 2007, the Danish daily Jyllands-Posten quoted the former Danish minister for Greenland, Tom Høyem, as saying I would not be surprised if Greenland again becomes a member of the EU... The EU needs the Arctic window and Greenland cannot alone manage the gigantic Arctic possibilities

.[305] Greenland has a lot of natural resources, and Greenland has, especially during the 2000s commodities boom, contracted foreign private companies to exploit some of them, but the cost is considered too high, as Greenland is remote and severely lacks infrastructure which has to be built. After 2013 prices declined so such efforts stalled.

The Brexit debate has reignited talk about the EU in Greenland with calls for the island to join the Union again.[306] In 2024, an opinion poll found that 60 percent of Greenland's population would vote in favour of re-joining the EU.[307]

The islands of Aruba and Curaçao, as well as Sint Maarten, are constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, while Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba are special Dutch municipalities. All are Overseas Countries and Territories (OCT) under Annex II of the EC treaty.[303] OCTs are considered to be "associated" with the EU and apply some portions of EU law. The islands are opting to become an Outermost Region (OMR) of the EU, a status in which the islands form a part of the European Union, though they benefit from derogations (exceptions) from some EU laws due to their geographical remoteness from mainland Europe. The islands are focusing on gaining the same status as the Azores, Madeira, the Canary Islands, and the French overseas departments.

When Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, and Saba were established as Dutch public bodies after the dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles (which was an OCT) in 2010, their status within the EU was raised. Rather than change their status from an OCT to an outermost region, as their change in status within the Netherlands would imply, it was decided that their status would remain the same for at least five years. After those five years, their status would be reviewed.[needs update]

If it was decided that if one or all of the islands wish to integrate more with the EU then the Treaty of Lisbon provides for that following a unanimous decision from the European Council.[308] Former European Commissioner for Enlargement Danuta Hübner has said before the European Parliament that she does not expect many problems to occur with such a status change, as the population of the islands is only a few thousand people.[citation needed]

The territories of French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Mayotte and Réunion are overseas departments of France and at the same time mono-departmental overseas regions. According to the EC treaty (article 299 2), all of these departments are outermost regions (OMR) of the EU—hence provisions of the EC treaty apply there while derogations are allowed. The status of the Overseas collectivity of Saint-Martin is also defined as OMR by the Treaty of Lisbon. New Caledonia and the overseas collectivities of French Polynesia, Saint-Barthelemy, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, and Wallis and Futuna are Overseas Countries and Territories of the EU.[303]

New Caledonia is an overseas part of France with its own unique status under the French Constitution, which is distinct from that of overseas departments and collectivities. It is defined as an "overseas country of France" under the 1998 Nouméa Accord, and enjoys a high degree of self-government.[309] Currently, in regard to the EU, it is one of the Overseas Countries and Territories (OCT).

As a result of the Nouméa Accord, New Caledonians voted in three consecutive independence referendums in 2018, 2020, and 2021. The referendums were to determine whether the territory would remain a part of the French Republic as a "sui generis collectivity", or whether it would become an independent state. The accords also specify a gradual devolution of powers to the local New Caledonian assembly. The results of all three referendums determined that New Caledonia would remain a part of the French Republic.

good neighbourly relations to be a criterion for the Republic of North Macedonia's membership in the EU; to use the official constitutional name of the Republic of North Macedonia instead of the short North Macedonia and the wording for the language should be the "official language" of the candidate country, not Macedonian.[18]

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.