Greater Lebanon

French League of Nations mandate (1920–1943) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The State of Greater Lebanon (Arabic: دولة لبنان الكبير, romanized: Dawlat Lubnān al-Kabīr; French: État du Grand Liban), informally known as French Lebanon, was a state declared on 1 September 1920, which became the Lebanese Republic (Arabic: الجمهورية اللبنانية, romanized: al-Jumhūriyyah al-Lubnāniyyah; French: République libanaise) in May 1926, and is the predecessor of modern Lebanon.

State of Greater Lebanon (1920–1926) État du Grand Liban دولة لبنان الكبير Lebanese Republic (1926–1943) République Libanaise الجمهورية اللبنانية | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1920–1943 | |||||||||

Location of Greater Lebanon (green) within the Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon | |||||||||

| Status | Mandate of France | ||||||||

| Capital | Beirut | ||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic French English Armenian | ||||||||

| Religion | Christianity Islam | ||||||||

| High Commissioner | |||||||||

• 1920–1923 (first) | Henri Gouraud | ||||||||

• 1944–1946 (last) | Étienne Paul Beynet | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1926–1934 (first) | Charles Debbas | ||||||||

• 1943 (last) | Émile Eddé | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1926–1927 (first) | Auguste Adib Pacha | ||||||||

• 1943 (last) | Riad Al Solh | ||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period | ||||||||

• State created | 1 September 1920 | ||||||||

| 23 May 1926 | |||||||||

| 22 November 1943 | |||||||||

• Withdrawal of French forces | 17 April 1946 | ||||||||

| Currency | Syrian pound (1920–1939) Lebanese pound (1939–1946) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The state was declared on 1 September 1920, following Decree 318 of 31 August 1920,[1] as a League of Nations Mandate under the proposed terms of the Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon which was to be ratified in 1923. When the Ottoman Empire was formally split up by the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, it was decided that four of its territories in the Middle East should be League of Nations mandates temporarily governed by the United Kingdom and France on behalf of the League. The British were given Palestine and Iraq, while the French were given a mandate over Syria and Lebanon.

General Gouraud proclaimed the establishment of the state with its present boundaries after support from the majority of Lebanese regardless of religion and with Beirut as its capital.[2] The new territory was granted a flag, merging the French flag with the Lebanese cedar.

Background

Summarize

Perspective

Name and Conception

The term Greater Lebanon alludes to the almost doubling of the size of the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate, the existing former autonomous region, as a result of the incorporation of the former Ottoman districts of Tripoli and Sidon as well as the Bekaa Valley. The Mutasarrifate had been established in 1861 to protect the local Christian population by the European powers under the terms of the Règlement Organique. The term, in French "Le Grand Liban", was first used by the Lebanese intellectuals Bulus Nujaym and Albert Naccache, during the buildup to the 1919 Paris Peace Conference.[3]

Nujaym was building on his widely read 1908 work La question du Liban, a 550-page analysis which was to become the foundation for arguments in favor of a Greater Lebanon.[4] The work argued that a significant extension of Lebanon's boundaries was required for economic success.[4] The boundaries suggested by Nujaym as representing the "Liban de la grande époque" were drawn from the map of the 1860-64 French expedition, which has been cited as an example of a modern map having "predicted the nation instead of just recording it".[5]

Paris Peace Conference

On 27 October 1919, the Lebanese delegation led by Maronite Patriarch Elias Peter Hoayek presented the Lebanese aspirations in a memorandum to the Paris Peace Conference. This included a significant extension of the frontiers of the Lebanon Mutasarrifate,[6] arguing that the additional areas constituted natural parts of Lebanon, despite the fact that the Christian community would not be a clear majority in such an enlarged state.[6] The quest for the annexation of agricultural lands in the Bekaa and Akkar was fueled by existential fears following the death of nearly half of the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate population in the Great Famine; the Maronite church and the secular leaders sought a state that could better provide for its people.[7] The areas to be added to the Mutasarrifate included the coastal towns of Beirut, Tripoli, Sidon and Tyre and their respective hinterlands, all of which belonged to the Beirut Vilayet, together with four Kazas of the Syria Vilayet (Baalbek, the Bekaa, Rashaya and Hasbaya).[6]

Proclamation

Following the peace conference, the French were awarded the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, under which the definition of Lebanon was still to be set by the French. Most of the territory was controlled by the Occupied Enemy Territory Administration, with the remainder controlled for a short time by the Arab Kingdom of Syria until the latter's defeat in July 1920. Following the decisive Battle of Maysalun, Lebanese Maronites openly celebrated the Arab defeat.[8]

On 24 August 1920, French Prime Minister Alexandre Millerand wrote to Archbishop Khoury: "Your country's claims on the Bekaa, that you have recalled for me, have been granted. On instructions from the French government, General Gouraud has proclaimed at Zahle's Grand Kadri Hotel, the incorporation into Lebanon of the territory that extends up to the summit of the Anti-Lebanon range and of Hermon. This is the Greater Lebanon that France wishes to form to assure your country of its natural borders."

World War II and Later history

Summarize

Perspective

Syria-Lebanon Campaign

During World War II when the Vichy government assumed power over French territory in 1940, General Henri Fernand Dentz was appointed as high commissioner of Lebanon. This new turning point led to the resignation of Lebanese president Émile Eddé on 4 April 1941. After five days, Dentz appointed Alfred Naqqache for a presidency period that lasted only three months. The Vichy authorities allowed Nazi Germany to move aircraft and supplies through Syria to Iraq where they were used against British forces. Britain, fearing that Nazi Germany would gain full control of Lebanon and Syria by pressure on the weak Vichy government, sent its army into Syria and Lebanon.[9]

After the fighting ended in Lebanon, General Charles de Gaulle visited the area. Under various political pressures from both inside and outside Lebanon, de Gaulle decided to recognize the independence of Lebanon. On 26 November 1941, General Georges Catroux announced that Lebanon would become independent under the authority of the Free French government.[9]

Levant Crisis and Independence

Elections were held in 1943 and on 8 November 1943, the new Lebanese government unilaterally abolished the mandate. The French reacted by throwing the new government into prison. Lebanese nationalists declared a provisional government, and the British diplomatically intervened on their behalf. In the face of intense British pressure and protests by Lebanese nationalists, the French reluctantly released the government officials on 22 November 1943, and accepted the independence of Lebanon.[10]

In October, the international community recognized the independence of Lebanon, which was admitted as a founding member of the United Nations along with Syria. On 19 December 1945, an Anglo-French agreement was eventually signed – both British forces from Syria and French forces from Lebanon were to be withdrawn by early 1946.

Government

Summarize

Perspective

The first Lebanese constitution was promulgated on 23 May 1926, and subsequently amended several times. Modeled after that of the French Third Republic, it provided for a bicameral parliament with Chamber of Deputies and a Senate (although the latter was eventually dropped), a President, and a Council of Ministers, or cabinet. The president was to be elected by the Chamber of Deputies for one six-year term and could not be reelected until a six-year period had elapsed; deputies were to be popularly elected along confessional lines.

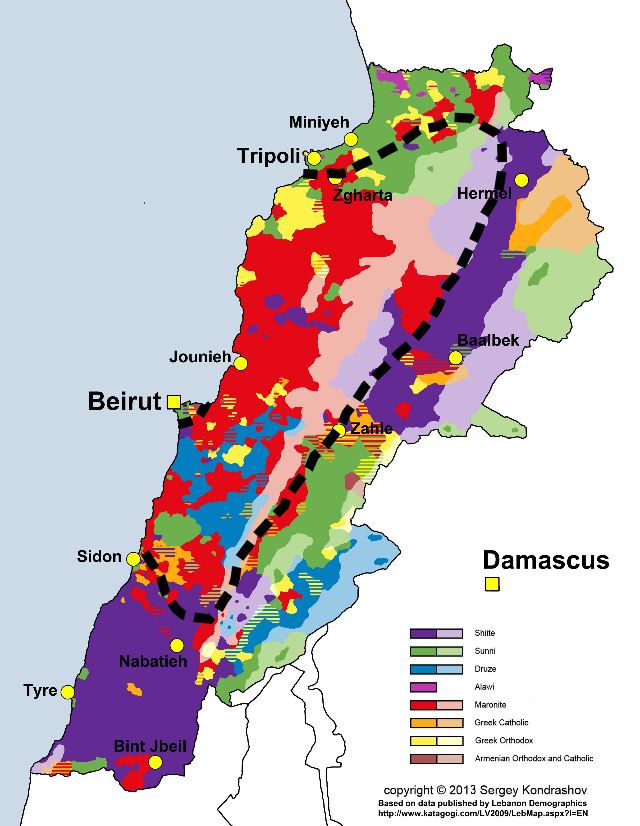

A custom of selecting major political officers, as well as top ranks within the public administration, according to the proportion of the principal sects in the population was strengthened during this period. Thus, for example, the president ought to be a Maronite Christian, the prime minister a Sunni Muslim, and the speaker of the Chamber of Deputies a Shia Muslim. A Greek Orthodox and a Druze would always be present in the cabinet. This practice increased sectarian tension by providing excessive power to the Maronite president (such as the ability to choose the prime minister), and hindered the formation of a Lebanese national identity.[11] Theoretically, the Chamber of Deputies performed the legislative function, but in fact bills were prepared by the executive and submitted to the Chamber of Deputies, which passed them virtually without exception. Under the Constitution, the French high commissioner still exercised supreme power, an arrangement that initially brought objections from the Lebanese nationalists. Nevertheless, Charles Debbas, a Greek Orthodox, was elected the first president of Lebanon three days after the adoption of the Constitution.

At the end of Debbas's first term in 1932, Bishara al-Khuri and Émile Eddé competed for the office of president, thus dividing the Chamber of Deputies. To break the deadlock, some deputies suggested Shaykh Muhammad al Jisr, who was chairman of the Council of Ministers and the Muslim leader of Tripoli, as a compromise candidate. However, French high commissioner Henri Ponsot suspended the constitution on 9 May 1932, and extended the term of Debbas for one year; in this way he prevented the election of a Muslim as president. Dissatisfied with Ponsot's conduct, the French authorities replaced him with Count Damien de Martel, who, on 30 January 1934, appointed Habib Pacha Es-Saad as president for a one-year term (later extended for an additional year).

Émile Eddé was elected president on 30 January 1936. A year later, he partially reestablished the Constitution of 1926 and proceeded to hold elections for the Chamber of Deputies. However, the Constitution was again suspended by the French high commissioner in September 1939, at the outbreak of World War II.

High Commissioners of the Levant

The High Commissioner of the Levant, named after 1941 the General Delegate to Syria and Lebanon, was the highest ranking authority representing France in the French-mandated countries of Syria and Lebanon.[12] Its office was based in Beirut, Lebanon in the Pine Residence and is now the official residence of the French ambassador to Lebanon. The office was first held by Henri Gouraud. Jean Chiappe should have held office on 24 November 1940 but the aircraft taking him to Lebanon was shot down by mistake by Italian air force taking part in the Battle of Cape Spartivento near Sardinia. The pilot, Henri Guillaumet, the other members of the crew including Marcel Reine, the two passengers, Chiappe, his leader of the cabinet, were killed. Last to hold office was Étienne Paul-Émile-Marie Beynet which began on 23 January 1944 and ended on 1 September 1946, 5 months after the withdrawal of French forces in Lebanon.[12]

Education

With the establishment of the Service de l'Instruction Publique (SIP), the Mandate’s institution responsible for overseeing Lebanon’s educational programme, the French authorities actively promoted French culture and the French language within Lebanese education.[13] Foreign mission schools were the main institutions for education, providing higher standards of education than under Ottoman administration, with no state-run system.[11] Although public educational institutions played a significant role in nation-state building throughout the Mandate era, the SIP contradicted this policy in Lebanon by permitting religious communities to establish their own private schools.[14]

Personal Status Law

With the establishment of the Mandate of Greater Lebanon, personal status of citizens were designated to officially recognized sects, altering the political dynamics between the communities that resided in the territory, granting legal authority in civil law disputes to sect-based courts.[15] The sect-based authority had at times inadvertently both affirmed and conflicted with the borders of Greater Lebanon, within civil legal matters such as divorce, as Linda Sayed argues that members of religious sects who lived outside of Greater Lebanon, which were given legal authority in Greater Lebanon could use its authority to contest legal decisions made in the Mandate territories they resided in such as the Mandate for Palestine.[16]

Demographics

The first and only official religious census of Greater Lebanon was carried out in 1932 which concludes that the population is roughly split equality between Muslims and Christians, the largest sects being Maronite Christianity, Sunni Islam and Shia Islam.[17]

| Christians | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sect | Population | Percentage |

| Maronite | 226,378 | 28.8 |

| Greek Orthodox | 76,522 | 9.7 |

| Melkite Catholic | 46,000 | 5.9 |

| Other | 53,463 | 6.8 |

| Total | 402,363 | 51.2 |

| Muslims | ||

| Sect | Population | Percentage |

| Sunni | 175,925 | 22.4 |

| Shiite | 154,208 | 19.6 |

| Druze | 53,047 | 6.8 |

| Total | 383,180 | 48.8 |

In total 785,542 people lived within the boundaries of Greater Lebanon in 1932.[18]

See also

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.