The Yale Record

Campus humor magazine of Yale University From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Yale Record is the campus humor magazine of Yale University. Founded in 1872, it is the oldest humor magazine in the United States.[3][4]

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

"Old Owl", The Record's "mascot" | |

| Editor in Chief | Lizzie Conklin |

|---|---|

| Online Editor in Chief | Debbie Lilly |

| Chair | Amelia Herrmann |

| Publisher | Erita Chen |

| Categories | Humor magazine |

| Founder | |

| Founded | 1872, Yale University |

| First issue | September 1872 |

| Based in | New Haven, Connecticut |

| Language | English |

| Website | www |

The Record is currently[when?] published eight times during the academic year and is distributed in Yale residential college dining halls and around the nation through subscriptions. Content from the magazine is made available online and entire issues can be downloaded in .pdf form.[5]

History

Summarize

Perspective

The Record began as a weekly newspaper, with its first issue appearing on September 11, 1872. Almost immediately, it became a home to funny writing (often in verse form), and later, when printing technology made it practical, humorous illustrations. The Record thrived immediately, and by the turn of the century had a wide circulation[weasel words] outside of New Haven—at prep schools, other college towns, and even New York City.[citation needed]

As Yale became one of the bellwethers of collegiate taste and fashion (especially for the younger universities looking East), so too The Record became a model—F. Scott Fitzgerald referred to the magazine as one of the harbingers of the new, looser morality of collegians of that time. But it wasn't just laughs The Record was serving up—during the 1920s, The Record ran a popular speakeasy in the basement of its building at 254 York Street (designed by Lorenzo Hamilton and completed in 1928).[4]

Early 20th century

Along with the Princeton Tiger Magazine (1878), the Stanford Chaparral (1899), and the Harvard Lampoon (1876), among many college humor magazines, The Record created a wide-ranging, absurdist style of comedy which mixed high-culture references with material dealing with the eternal topics of schoolwork, alcohol, and sex (or lack thereof). Comedy first published in the magazine was re-printed in national humor magazines like Puck[6] and Judge.[7]

At first petting was a desperate adventure...As early as 1917, there were references to such sweet and casual dalliance in any number of The Yale Record...

F. Scott Fitzgerald, "Echoes of the Jazz Age" (November 1931)[8]

In 1914, J.L. Butler of The Yale Record and Richard Sanger of The Harvard Lampoon created the first annual banquet of the College Comics Association, which drew representatives from 14 college humor magazines to New Haven.[9] The college humor style influenced—or in some cases led directly to—the Marx Brothers, The New Yorker, Playboy, Mad magazine, underground comics, National Lampoon, The Second City, and Saturday Night Live.[4]

The character "Whit" (pronounced "wit") in the Sinclair Lewis story Go East, Young Man drew caricatures for the Yale Record.[10]

Mid-20th century

From the 1920s to the 1960s, The Record placed special emphasis on cartooning, which led many of its alumni to work at Esquire magazine and especially The New Yorker. Record cartoonists during this time period included Peter Arno, Reginald Marsh, Clarence Day, Julien Dedman, Robert C. Osborn, James Stevenson, William Hamilton and Garry Trudeau.

From 1920 through the 1940s, many Record staffers and alums contributed to College Humor, a popular nationally distributed humor magazine. Additionally, comedy first published in The Record was re-printed in national humor magazines like Life[11] and College Humor.

By the late 1940s, the magazine's ties to The New Yorker were so strong that designers from that magazine consulted on The Record's layout and design.

By the 1950s, the Record had established the "Cartoonist of the Year" award, which brought people like Walt Kelly, the creator of Pogo, to New Haven to dine and swap stories with the staff.

In the early 1960s, cartoons and comic writing from the magazine were regularly re-printed in Harvey Kurtzman's Help!,[12] a satirical magazine that helped launch the careers of Monty Python's Terry Gilliam, R. Crumb, Woody Allen, John Cleese, Gloria Steinem and many others.

In the late 1960s, the magazine played an integral role in editor-in-chief Garry Trudeau's creation of his epochal strip Doonesbury.[4] Trudeau published the pre-syndication Doonesbury collection Michael J. (1970) through The Yale Record.[13] In addition to editing the Record, Trudeau (and Record chairman Tim Bannon, basis of Doonesbury attorney T.F. Bannon of Torts, Tarts & Torque) organized Record events such as a successful Annette Funicello film festival, a Tarzan film festival (with guest Johnny Weissmuller) and a Jefferson Airplane concert featuring Sha Na Na.[14]

Recent years

The 1970s and 1980s are known as the "Dark Ages" amongst Record staffers. Economic conditions in New Haven were abysmal and despite its impressive pedigree, The Record sputtered along, self-destructed and was revived numerous times throughout this period. Boards were convened and issues were published intermittently in 1971–1981, 1983, and 1987.[15][16][17]

Then in 1989, Yale students Michael Gerber and Jonathan Schwarz relaunched The Record for good.[18] Their more informal, iconoclastic version of The Record proved popular, and a parody of the short-lived sports newspaper The National garnered national media attention.[19] Gerber also created an ad hoc advisory board from Record alumni and friends, including Mark O'Donnell, Garry Trudeau, Robert Grossman, Harvey Kurtzman, Arnold Roth, Ian Frazier, Sam Johnson and Chris Marcil.

In the fall of 1992, Record contributor Ryan Craig[20] founded popular Yale tabloid the Rumpus.

While The Record continues[when?] to publish paper issues, the magazine began publishing web content on April 1, 2001.

Themed issues

Summarize

Perspective

This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (October 2016) |

Each issue of the current magazine features a particular theme. Aspects of the magazine include:

- Snews - One-liners in the form of headlines.

- Mailbags - Humorous letters to the editor, historical figures, or inanimate objects.

- The Editorial - Written by the editor in chief of the magazine each issue, giving a brief overview of the contents and making of the issue.

- Cartoons - Captioned, "New Yorker style" cartoons that hail back to the magazine's early beginnings.

- Lists and Features - Staff generated content pertinent to the magazine's theme.

Parodies

From time to time, The Record publishes parodies. These include (but are not limited to):

- The Yale Daily Record, a parody of the Yale Daily News (May 2016)

- "Yale's 50 Best Personalities," a Yale Rumpus parody (April 2015)

- The Yale Daily Record, a parody of the Yale Daily News (April 2014)

- Yale Bulldog Days Program Parody (April 2013 – 2016)

- "The Please Your Man Issue" (April 2009), a parody of Cosmopolitan

- "The Yale Protest Club: Fill Out Your Very Own YPC Petition!" (April 2008)

- "Parents' Weekend Brochure" (October 2007)

- Yale Blue Book Parody (September 2007)

- "Yale Map" (for visiting pre-frosh) (April 2007)

- Yale Blue Book Parody (September 2006)

- "Yale's 50 Best Personalities," a Yale Rumpus parody (February 2006)

- Yale Blue Book Parody (August 2005)

- "YaleRecordStation" (March 2004), parody of "YaleStation"

- Yale College Coarse Critique (September 2002), a parody of the Yale Course Critique

- Yale Handbook Parody (September 2001)

- The New York Tomes (April 1, 1999), a parody of The New York Times

- The Yale Harold (1992), a parody of the Yale Herald

- Parody of The National Sports Daily (April 1991)

- Football Program Parody (November 1990)

- New Haven Abdicate (1990), a parody of the New Haven Advocate

- National Enquirer parody (1975)

- New York Times parody (1974)

- Yale Daily News parody (1970)[17]

- The Reader's Dijest (1967), a nationally distributed parody of The Reader's Digest

- Parody of The New York Times Magazine (1966)

- Parody of the Yale Alumni Magazine (1965)

- Sports Illstated (1965), a parody of Sports Illustrated[21]

- Pwayboy (1964), a parody of Playboy

- Twue (1963), a parody of True

- Liff (1962), a parody of Life [17]

- "Fallout Protection" (1962) from the Department of Offense

- Yew Norker (1961), a parody of The New Yorker[22]

- Reader's Digestion (1960), a parody of Reader's Digest

- Timf (1960), a parody of Time[17]

- Sports Illiterate (1959), a parody of Sports Illustrated[21]

- Ployboy (1958), a parody of Playboy

- Daily Mirror Parody (1957), a parody of the New York Daily Mirror

- Le Nouveau Yorkeur (1956), a parody of The New Yorker[23]

- Yale Alumninum Manganese (1955), a parody of the Yale Alumni Magazine

- Esquirt (1955), a parody of Esquire

- Tale (1954), a parody of Male

- Yale Daily News parody (1954)

- Paunch (1952), a parody of Punch

- Yale Daily News parody (1952)

- Yale Daily News parody (1951)

- The Smut! Issue (1951)

- Yale Daily News parody (1949)[17]

- Record Comics (1949), featuring "Supergoon", a parody of "Superman", and "Hotshot Stacy", a parody of "Dick Tracy"

- The Shattering Review of Literature (1949), a parody of The Saturday Review of Literature

- Happy Hollywood (1947), a movie magazine parody

- New York's Fiction Newspaper (1946), a parody of the Daily News[24]

- Record's Digest (1943), a parody of Reader's Digest

- Phlick (1939), a parody of photo magazines[17]

- Parody of The Harvard Crimson (1939)[25]

- Yale Daily News parody (1938)

- Real Spicy Horror Tales (1937), parody of pulps

- Yale Daily News parody (1934)

- Vanity Fair parody (1933)

- The New Yorker parody (1928 - 1929)

- Parody of Time (1928 - 1929)

- Yale Daily Clews (1927), a parody of the Yale Daily News

- Yale Record's Film Fun Number (1927), a parody of Film Fun

- Collegiate Comicals (1926), a parody of college comics[17]

Master's Teas

Summarize

Perspective

Throughout the year, the Record invites notable figures from the world of comedy to "Master's Teas", informal interviews hosted by the Record in conjunction with residential colleges, at which tea is, in fact, not even served upon request. While residential colleges frequently organize Master's Teas, The Yale Record is known for its humorous ones. Guests have included:

- National Lampoon's co-founding editor Henry Beard

- George Carlin of FM & AM, Class Clown and Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure fame

- Senator Al Franken of Saturday Night Live, The Al Franken Show and Trading Places fame

- Brian McConnachie of National Lampoon, SCTV and Caddyshack fame

- Tony Hendra of National Lampoon and This Is Spinal Tap fame

- Robert Mankoff, cartoon editor of The New Yorker

- The Onion co-founding editor Scott Dikkers

- The Colbert Report head writer Allison Silverman

- Carol Kolb, former editor-in-chief of The Onion and former head writer of The Onion News Network; and Jack Kukoda, former head writer for Onion SportsDome, also known for The Onion News Network, Community, China, IL and Wilfred

- Arnold Roth, cartoonist[26]

- Adam McKay, former head writer of Saturday Night Live and co-writer/director of Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy

- Upright Citizens Brigade co-founders Matt Walsh and Ian Roberts, and Lawrence Blume, director of Martin & Orloff

- Fred Armisen of Portlandia and Saturday Night Live

- Stella (David Wain, Michael Ian Black and Michael Showalter)

- Alec Baldwin of 30 Rock, Knots Landing, Beetlejuice, The Cooler, The Hunt for Red October, The Aviator, Blue Jasmine and MSNBC's short-lived Up Late with Alec Baldwin

- Neil Goldman of Scrubs and Community

- Comedy writer Mike Sacks

- Philip Seymour Hoffman, Oscar-winning actor known for Boogie Nights, The Big Lebowski and Capote

- Demetri Martin

- Wesley Willis

- John Mulaney, Marika Sawyer and Simon Rich of Saturday Night Live

- Comic artist Kazu Kibuishi, known for Copper[27]

Pranks

- 1902: The Yale Record pranked temperance activist Carrie Nation. Pretending to be a Yale temperance group, they brought her to Yale. During her visit, they took a picture with her. At the time, nighttime indoors photography required turning off all artificial lights before exposing a photographic plate and illuminating the scene with a single flashbulb. However, in the darkness, the students from The Record pulled out a beer stein and other props to create the impression of what the Yale Daily News would characterize as a "Bacchanalian orgy."[28]

- 2015: The Yale Record hosted a mock protest on Broadway. The students called for Yale administrators to bring a second Kiko Milano store. “When we heard that Yale had decided to replace the affordable food store up on Broadway with Kiko Milano and Emporium DNA, we were really excited to have the chance to buy more luxury products at Yale because that was really hard before,” Gertler said.[29]

"Old Owl"

For over a century, the mascot of the Record has been "Old Owl", a congenial, largely nocturnal, 360-degree-head-turning, cigar-smoking bird who tries to steer the staff towards a light-hearted appreciation of life and the finer things in it.

"Old Owl" is a Cutty Sark connoisseur of some repute and enthusiasm. In artists' sketches, he is often portrayed as anthropomorphic.

Documenting the birth of American football

Summarize

Perspective

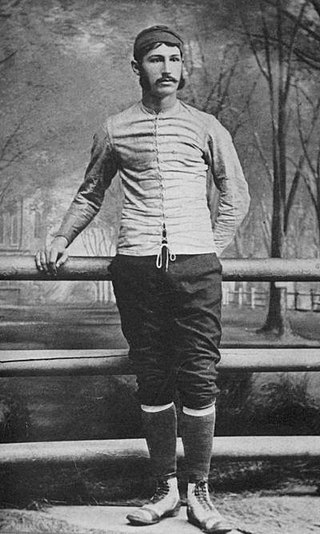

The Yale Record of the late nineteenth century chronicled much of the birth of American football:

- The Yale Record and the Nassau Literary Magazine of Princeton printed the only accounts of the first Yale-Princeton game (1873),[30] the first game played using the Football Association Rules of 1873. These were the first consolidated rules in American football; before this, each of the handful of colleges that had football teams played by its own set of rules.[31]

- The Yale Record documented the organization and playing of the first Harvard-Yale game (1875). Yale proposed the game. Harvard, which had just rejected an offer to join the association of soccer-playing colleges, accepted the challenge, on condition that the game be played with what were essentially rugby rules. These were the rules used by Harvard, different to the rules of the other colleges. Yale agreed to this condition and was soundly defeated.[32] In reflecting on this crushing defeat, one Record editor blamed the loss on Yale's willingness to adopt the "concessionary rules", complaining that Yale "should not have given so much to Harvard."[33]

- The Yale Record documented the creation of the Intercollegiate Football Association in 1876. The Harvard-Yale game of 1875 ushered in a national shift from the soccer form to the rugby form of football. Within a year, Princeton had adopted the rugby rules, and in the fall of 1876, Columbia joined Princeton and Harvard to form the Intercollegiate Football Association, which officially adopted English rugby rules. Although Yale agreed to adopt English rugby rules and played Harvard, Princeton and Columbia, they did not join the association as they favored a game with eleven rather than fifteen players, as well as points allowed only for kicked goals.[34]

- The Yale Record documented the creation of the first American football championship. The Intercollegiate Football Association created the first championship game, which was played between Princeton and Yale on Thanksgiving Day in 1877.[34] The teams tied to share the first national championship.

- The Yale Record documented Walter Camp's innovations in rules and scoring, notably the reduction of fifteen players to eleven, the establishment of the line of scrimmage and the snap, as well as the creation of downs.

Coining the term "hot dog"

Summarize

Perspective

They contentedly munched hot dogs during the whole service.

The Yale Record (October 19, 1895)

According to David Wilton, author of Word Myths: Debunking Linguistic Urban Legends (2009), The Yale Record is responsible for coining the term "hot dog":

There are many stories about the origin of the term hot dog, most of them are false. Let us start with what we know. The first known use of the term is in the Yale Record of October 19, 1895...The reason why they are called hot is obvious, but why dog? It is a reference to the alleged contents of the sausage. The association of sausages and dog meat goes back quite a bit further. The term dog has been used as a synonym for sausage since at least 1884...[35]

The magazine published its own history of The Yale Record/"hot dog" connection in its April 1998 issue.

However, the term hot dog in reference to the sausage-meat appears in the Evansville (Indiana) Daily Courier (September 14, 1884):

even the innocent 'wienerworst' man will be barred from dispensing hot dog on the street corner.[36][37]

And hot dog was used to mean a sausage in casing in the Paterson (New Jersey) Daily Press (31 December 1892):

the 'hot dog' was quickly inserted in a gash in a roll.[37]

Bladderball

Bladderball was a game traditionally played by students at Yale, between 1954 and 1982, after which it was banned by the administration.

It was created by Philip Zeidman as a competition between The Yale Record, the Yale Daily News, The Yale Banner and campus radio station WYBC. It was eventually opened to all students, with teams divided by residential college.[38]

Notable alumni

Summarize

Perspective

Notable Yale Record alumni include (but are not limited to):

- Franklin Abbott[39]

- Cecil Alexander[25]

- William Anthony[40]

- Peter Arno[41]

- Grosvenor Atterbury[42]

- Thomas Rutherford Bacon[43]

- Donn Barber[44]

- Hugh Aiken Bayne[45]

- Daniel Levin Becker[46]

- Lucius Beebe[47]

- Clifford Whittingham Beers[48]

- William Burke Belknap[49]

- Stephen Vincent Benét[50]

- William Rose Benet[51]

- Senator William Benton[52]

- Peter Bergman and Phil Proctor[53] of The Firesign Theatre

- Walker Blaine

(editorial board, 1874–1875)[54] - Edward Anthony Bradford[55]

(editorial board, 1872–1873)[1] - Maj. Gen. Preston Brown[49]

- C. D. B. Bryan[56]

- Howard S. Buck[57]

- John Chamberlain[58]

- Walter B. Chambers[59]

(editorial board, 1886–1887)[1] - Yahlin Chang[60]

- Roy D. Chapin Jr.[61]

- George Shepard Chappell[62]

- Cherry Chevapravatdumrong[63]

- William Churchill[64]

- Gerald Clarke[65]

- River Clegg[66]

- Thomas Cochran[67]

- Elliot E. Cohen[68]

- Charles Collens[69]

- Paul Fenimore Cooper[70]

- James S. Copley[61]

- James Ashmore Creelman[71]

- Raymond Crosby[72]

- Walter J. Cummings[61]

- Ian Dallas[73]

- Clarence Day[74]

- George Parmly Day[75]

- Julien Dedman[76]

- William Adams Delano[49]

- Edward Jordan Dimock[70]

- Warren DeLano[77]

- Rep. Charles S. Dewey[78]

- William Henry Draper III[79]

- Fairfax Downey[70]

- Jaro Fabry[80]

- John C. Farrar[81]

- Henry Johnson Fisher[82]

- Matt Fogel[83]

- Karin Fong[84]

- Henry Ford II[25]

- Jay Franklin[85]

- Asa P. French[86]

(editorial board, 1881–1882)[1] - Michael Gerber[77]

- Arthur Lehman Goodhart[70]

- Ben Greenman[87]

- A. Whitney Griswold[88]

- Robert Grossman[89]

- Philip Hale[90]

(editorial board, 1875–1876)[1] - William Hamilton[91]

- Eddie Hartman[60]

- Wells Hastings[92]

- Clovis Heimsath[93]

- Geoffrey T. Hellman[94]

- David Hemingson

- Jerome Hill[95]

- Hrishikesh Hirway[73]

- Wilder Hobson[94]

- Brian Hooker[96]

- John Hoyt[97]

- Cyril Hume[98]

- Walter Hunt[99]

- Richard Melancthon Hurd[100]

- Rex Ingram[101]

- Samuel Isham[102]

(editorial board, 1874–1875)[1] - Frank Jenkins[103]

(editorial board, 1873–1874)[1] - Ralph Jester[70]

- Tom Loftin Johnson[104]

- Lorenzo Medici Johnson[105]

- Gordon M. Kaufman[106]

- Stoddard King[107]

- Eugene Kingman[108]

- John Knowles[109]

- Brendan Koerner[110]

- Jason Koo[111]

- Arthur Kraft[112]

- Jack Kukoda[113]

- Dick Lemon[114]

- Robert L. Levers, Jr.[115]

- David Litt[116]

- Huc-Mazelet Luquiens[49]

- Dwight Macdonald[117]

- Reginald Marsh[118]

- Grant Mason Jr.[119]

- Tex McCrary[120]

- Thomas C. Mendenhall[121]

- Charles Merz[122]

- Eric Metaxas[123]

- Glen Michaels[93]

- Henry F. Miller[61]

- Grant Mitchell[49]

- Mahbod Moghadam[124]

- Gouverneur Morris[125]

- John C. Nemiah[25]

- Augustus Oliver[126]

- Robert C. Osborn[127]

- Jack Otterson[128]

- Greg Pak[129]

- Ed Park[130]

- Sidney Catlin Partridge[131]

(editorial board, 1879–1880)[1] - Senator John Patton Jr.[132]

(editorial board, 1874–1875)[1] - Ronald Paulson[93]

- Rep. Alfred N. Phillips[70]

- Rep. James P. Pigott[133]

(editorial board, 1876–1877) - Cole Porter[134]

- John A. Porter[135]

(editorial board, 1877–1878)[1] - Vincent Price[136]

- Kenneth Rand[137]

- Erik Rauch[138]

- John Francisco Richards II[139]

- Clements Ripley[70]

- Governor Henry Roberts

(editorial board, 1875–1876)[140] - James Gamble Rogers

- Henry T. Rowell[97]

- Stanley M. Rumbough Jr.[141]

- John M. Schiff[142]

- Preston Schoyer[143]

- Charles Green Shaw[144]

- Howard Van Doren Shaw[145]

- Michael Shear[111]

- Alan B. Slifka[79]

- James Stevenson[93]

- Brandon Tartikoff

- Malcolm Taylor and Charles Reed[121]

- John Templeton[146]

- Sherman Day Thacher[147]

(editorial board, 1882–1883)[1] - Daniel G. Tomlinson[148]

- Garry Trudeau[149]

- Sonny Tufts[150]

- Frank Tuttle[151]

- Jose Antonio Sainz de Vicuna[106]

- George Edgar Vincent[152]

(editorial board, 1884–1885)[1] - Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr.[121]

- Ed Wasserman[153]

- Hillary Waugh[141]

- Herman Armour Webster[154]

- Edward Whittemore

- Herbert Warren Wind[155]

- Jerome Zerbe[128]

Guest contributors

Guest contributors to The Record have included:

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.