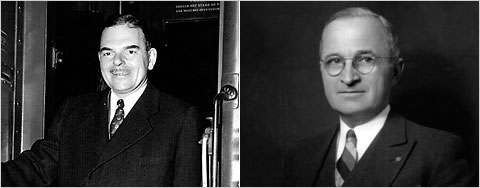

Gov. Thomas E. Dewey was defeated by Harry S. Truman in the 1948 presidential election. Two years later, Truman’s dislike for Dewey touched New York politics. (Photos: The New York Times)

Gov. Thomas E. Dewey was defeated by Harry S. Truman in the 1948 presidential election. Two years later, Truman’s dislike for Dewey touched New York politics. (Photos: The New York Times)Following is the script of the weekly “Only in New York” audio podcast. Listen at left or download the mp3 to a portable player. Browse a list of other Times podcasts here.

Mike Royko was right. Years ago, he proposed that Chicago adopt the slogan, “Ubi Est Mea.” It sounds more high-minded in Latin. The motto means: Where’s mine?

What Royko meant was that while most politics is local, it’s all personal.

Which helps explains why the governor of Illinois is accused of trying to peddle Barack Obama’s Senate seat

to the highest bidder. And also why whoever Governor Paterson appoints to succeed

Hillary Rodham Clinton of New York won’t

have to run for re-election next year.

Instead, if that appointee wants to keep the Senate seat, he or she will have to go before the voters in 2010 and run for re-election again in 2012.

It all goes back to Harry Truman’s hatred of Tom Dewey.

A half-century may seem like a long time to perpetrate a grudge. But for all the focus on Illinois this week, that’s how the political process typically works in New York.

Politics is personal.

Our election law is very complicated — my friend Jerry Goldfeder just wrote an entire book about it. It doesn’t take too much reading between the lines to understand that democracy has historically taken a back seat to contradictory goals: leveraging the law to perpetuate incumbency.

I couldn’t find evidence in the Truman archives. But Justin Feldman, a prominent Manhattan lawyer who was close to several of the president’s confidants, swears this story is true.

It’s 1950. Two years after barely losing to President Truman, Dewey decides not to run again for governor of New York. The Democrats are poised to finally recapture the governorship and sweep the state. But they need to generate the traditionally heavy Democratic vote in New York City. That’s what had happened the year before, in 1949. An interim Republican senator, John Foster Dulles, lost to Herbert Lehman because of the big New York mayoral vote that re-elected Bill O’Dwyer.

In 1950, though, there’s no mayoral election. No problem.

“What,” says Ed Flynn, the wily Democratic boss of the Bronx, “if O’Dwyer resigned?”

O’Dwyer was ailing, physically and politically. Flynn conferred with Truman — no fan of O’Dwyer. But given the prospect of a Democratic sweep in New York State, Truman agreed to name the mayor ambassador to Mexico. Which, conveniently, meant a new mayor would have to be elected that November, the same time as the governor and senator.

To make this long story shorter, New York Democrats were divided. Dewey got back in the gubernatorial race and won a third term. The next year, Republicans introduced legislation that would bar a race for mayor of New York in any general election when state or national officials were being chosen, too. (2009 is a mayoral election year.)

Here’s another fact for Senator Clinton’s potential successors to consider: Interim Senate appointees haven’t fared very well. Since 1960, governors have appointed some 50 interim senators. Two were named just last year. Of the 38 who ran for election, only 18 won. New York’s most recent interim appointee, Charles Goodell, lost when he sought a full term in 1970.

Given the state’s political and financial deficit, Governor Paterson might be tempted to do Illinois one better and just auction the Senate seat on eBay.

He also might be tempted to extricate himself from the scrum in Albany by selecting himself. But that record isn’t encouraging either. Over the last 75 years, nine governors have filled Senate vacancies by appointing themselves. Only one — Albert Chandler of Kentucky in 1939 — ran and retained his seat. No wonder his nickname was Happy.

Speaking of “Where’s Mine?” … Senator Clinton could do the state a favor by resigning before her confirmation as secretary of state. With at least seven other Democratic freshmen being sworn in on Jan. 3, resigning early would give her successor more seniority.

Her spokesman says “it would be presumptuous to assume confirmation before the full Senate actually takes up the matter.”

After all, only a decade ago, William Weld quit as governor of Massachusetts to accept a job from President Clinton. But his fellow Republicans in the Senate failed to confirm him. The nomination, by the way, was to be ambassador to Mexico — following in the footsteps of Bill O’Dwyer.

Comments are no longer being accepted.