There is a prevailing stereotype among the American public at large about French cinema. The French, the argument goes, are unbearably pretentious, turning out long, ponderous Art films (capital-A) about existential ennui and beautiful people smoking cigarettes in black and white. French cineastes look down their noses at American moviegoers, and when Americans profess to be lovers of French film, they mostly do so to gain admiration from their peers at their favorite overpriced coffee shop. The punchline to this stereotype is a second stereotype, one just as cherished by derisive Americans: that the French, for all their airs and affectations, are inexplicably enraptured with the late Jerry Lewis.

There is, of course, some level of truth to both of these caricatures. The French New Wave was built, to some extent, on pretense; its initial offerings were among the first films created as conscious artistic statements rather than populist entertainment, and the first to manipulate and rethink the “rules” that had fallen into place over cinema’s first half-century. And Jean-Luc Godard (consciously or not, the director most people are thinking of when they conjure “French Cinema”) is ridiculous; he has cultivated an enfant terrible persona which persists to this day, and has made several films with the specific goal of galling and frustrating the audience. If anyone relishes the idea of “difficult” French cinema, it’s likely Godard.

Yet that second stereotype is the tip of an iceberg that to some extent punctures and deflates the first. The French do afford the late Mr. Lewis a level of respect rare in his homeland, but it’s not just him. Many of the Nouvelle Vague’s founding fathers, including Francois Truffaut, Jean-Pierre Melville, and Godard himself, were critics before they were filmmakers, and come from a place of deep, abiding love of film. In particular, all seem to have a fondness for the most crowd-pleasing of genres: gangster movies, slapstick comedy, musicals, the films of Hitchcock and John Ford. Once you allow yourself to break through the arty artifice of their films, you’ll find a surprisingly energetic core. These films aren’t just important– they’re fun.

Perhaps no film embodies the infectious spirit of the New Wave than Godard’s Bande à part, better known stateside as Band of Outsiders. To the uninitiated, it can seem daunting: yes, it’s black and white, and yes, its protagonists (including Godard’s deathless muse Anna Karina) are both impossibly beautiful and profoundly bored. But it’s also thrilling, funny, and straight-up silly enough to surprise the casual moviegoer. In the film’s most famous scene, Karina and her compatriots stage an elaborate dance in the middle of a restaurant, only to have the music occasionally drop out and Godard himself describe the characters’ feelings in clinical detachment. Pretentious? Sure. But also sexy, dazzlingly cinematic, and fucking funny. This humor runs through the film, from the trio’s pre-Griswold dash through the Louvre to their hobby of reading grisly news articles to each other by the riverbed, and perfectly capture the proto-punk sensibility that makes him more than stuffy college material. Quentin Tarantino clearly took notes; he named his production company “A Band Apart,” and has admitted the film’s influence on Vincent and Mia’s famous twist-off (in typical form, Godard has deadpanned that he’d have preferred Tarantino just cut him a check). So check it out– or wait for the next episode, in CinemaScope and Technicolor, with Odile and Franz in the tropics.

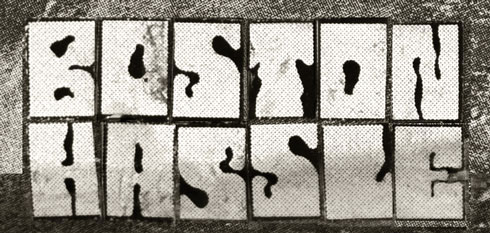

Band of Outsiders

1964

dir. Jean-Luc Godard

95 min.

Screens Monday, 9/18, 7:00pm @Coolidge Corner Theatre

Part of the ongoing series: Big Screen Classics