Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Ilioinguinal nerve (IIN) or iliohypogastric nerve (IHN) neuralgia is a frequent source of pain in the lower abdomen and upper thigh. It is common after lower abdominal surgery, particularly hernia surgery, or after injury to the abdominal wall. It presents with severe pain in the lower quadrant radiating to the groin and thigh. Patients are unable to engage their abdominal muscles; hence, their daily life is severely limited. Full or partial disability, even in a young population, is not uncommon. The diagnosis is mainly based on the history and physical exam, but exclusion of other conditions and diagnostic injections are also part of the work-up. Some cases gradually improve with conservative measures; however, if conservative measures fail, the treatment is challenging and includes various minimally invasive modalities like hydrodissection, pulse radiofrequency treatment, cryoablation, and spinal cord stimulation or peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS). No high-quality studies support any of these modalities.

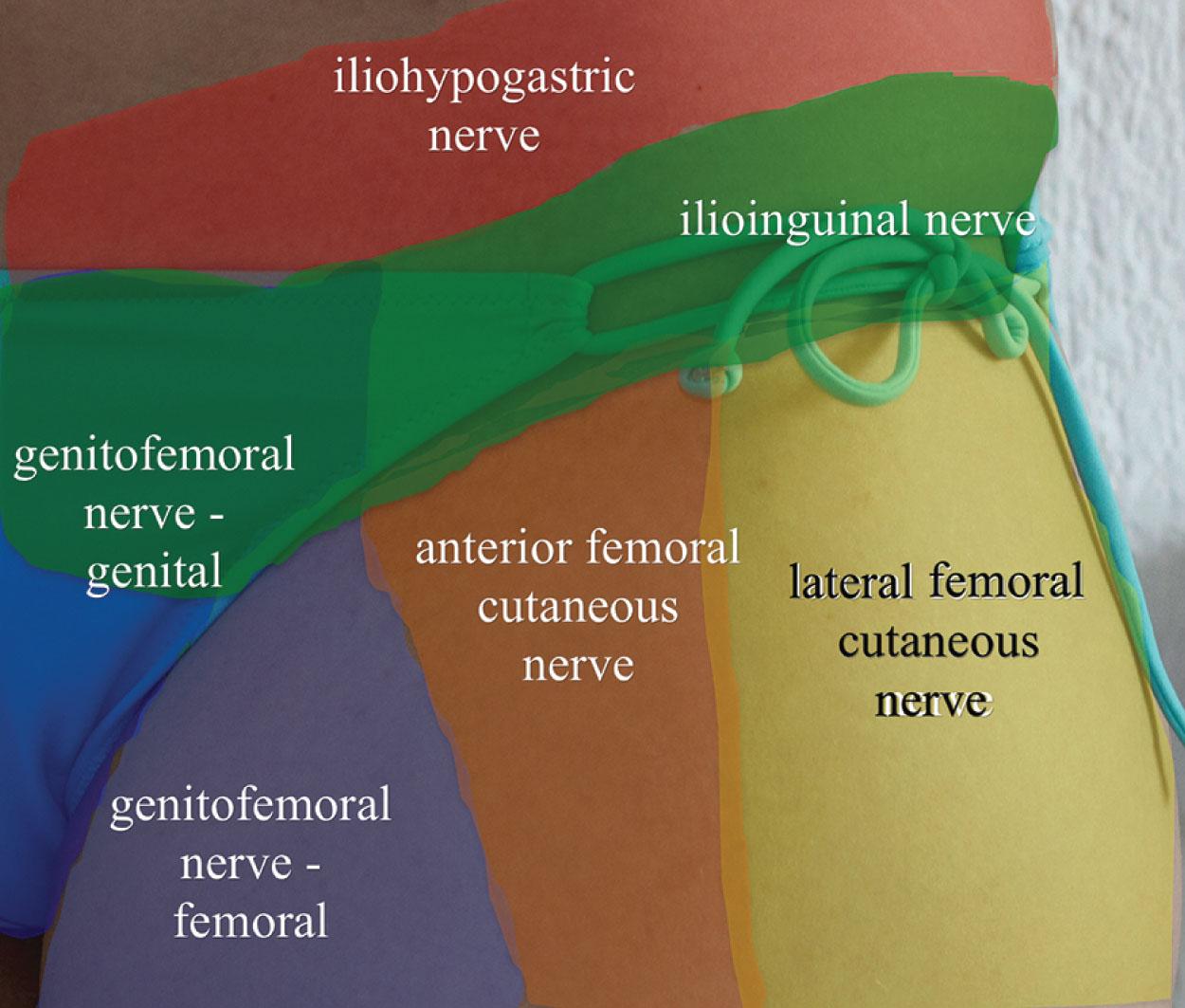

IIN or IHN neuralgia can cause pelvic and genital pain and mimic intrabdominal pathologies as well. It usually presents with a triad of inguinal burning pain, abnormal sensation in the cutaneous innervation area of the nerves ( Fig. 17.1 ), and tenderness to palpation around the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). Pain may radiate to the inguinal region or genitalia, but usually does not radiate below the knee. In severe cases, the nerve injury may result in hair loss and trophic changes in the anterior surface of the scrotum, root of penis in males, or labia majores or mons pubis in females, similarly to the well-known and recognized complex regional pain syndrome of the extremities.

Pain is usually aggravated both by extension and contraction of the abdominal muscles (positive Carnett’s sign) ( Fig. 17.2 ). Patients are unable to carry any significant weight, sit up from a supine position without pain, and/or engage in sexual activity. Pain is usually decreased by complete relaxation of the abdominal muscles. In severe cases, abdominal muscle bulge can occur due to the loss of motor function of the innervated muscles (internal oblique or transverse abdominis), which can be mistaken for an abdominal or inguinal hernia.

The etiology of IIN and IHN neuralgia could be traumatic or idiopathic. Most cases result from surgery (herniorrhaphy, trocar insertion from laparoscopic operations, appendectomy, hysterectomy, abdominoplasty, orchidectomy) or from blunt abdominal trauma, femoral catheterization, lower external oblique aponeurosis disruption, stretch trauma (e.g., pregnancy), retroperitoneal tumors, and endometriomas in the canal. The prevalence of IHN/IIN neuralgia after hernia repair is estimated to be between 5% and 35%. Pain may start immediately after the surgery if there is a direct damage to the nerve by the surgery, or may start a few weeks or sometimes even months later as scar tissue forms and tightens around the affected nerve or inflammation ensues around the implanted mesh or staples.

Although idiopathic IHN/IIN neuralgia is a rarity, it has been reported. It could result from the musculoaponeurotic spectrum, such as tight fascial planes causing entrapment at the paravertebral or inguinal area, iliac crest, or rectus muscle border. Even in these “idiopathic” cases, careful history often reveals traumatic injury that includes heavy lifting, with a feeling of a “pop” in the abdominal area.

Differential diagnosis includes: important intraabdominal and pelvic pathologies (which are usually excluded by the time the patient gets to a pain physician), recurrent herniation (difficult to assess, may cause a diagnostic challenge as imaging modalities often do not give a definitive answer), infection, abscess, suture granuloma, genitofemoral neuralgia, lumbosacral radiculopathy and plexopathy, abdominal cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome, or sacroiliac and iliolumbar pathology because those may refer pain to the groin. History-taking should include questions related to these conditions too.

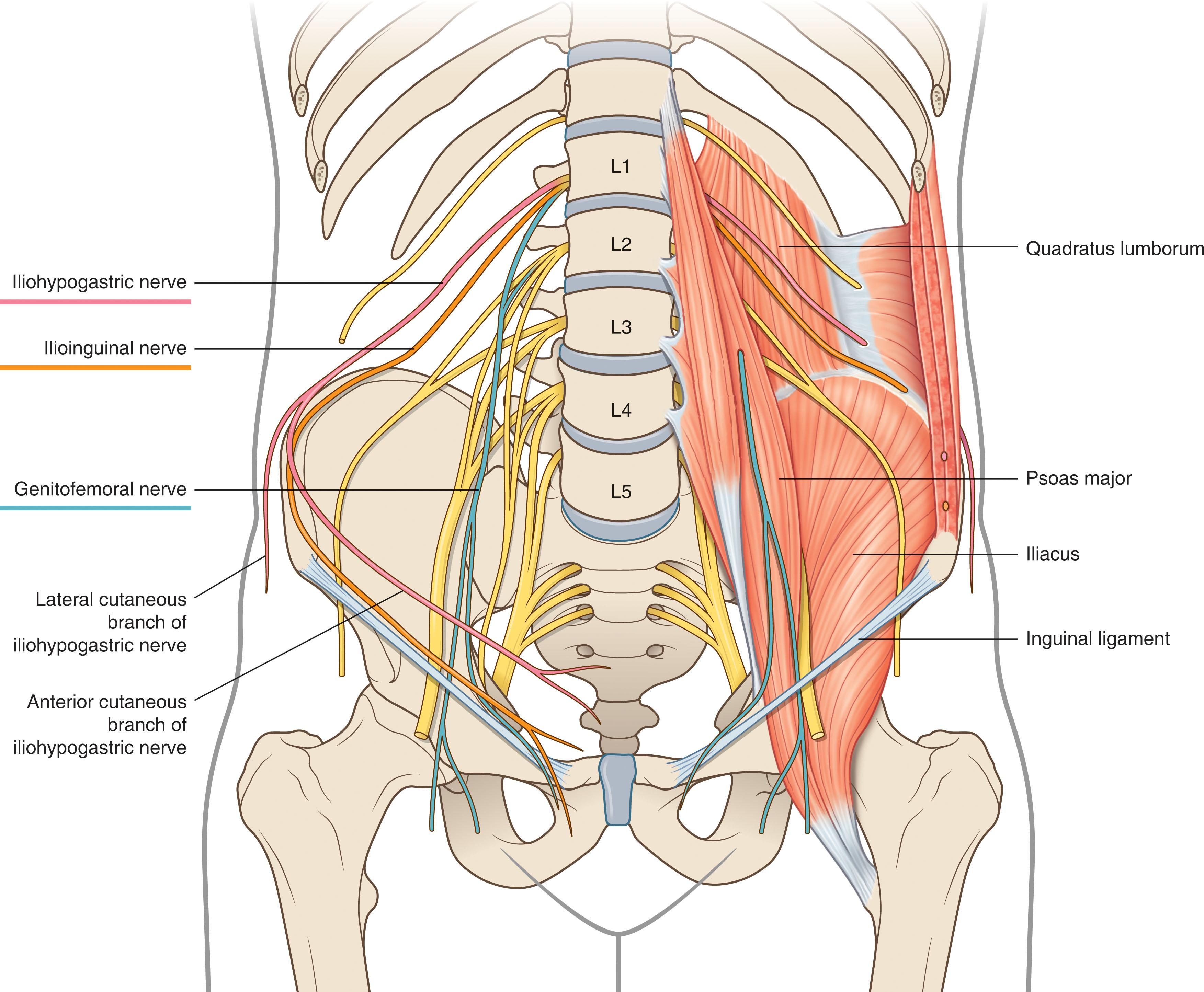

The IHN and IIN originate from the anterior rami of the T12 and L1 nerve roots. The nerves emerge from the lateral border of the psoas major muscle and travel retroperitoneally on the anterior surface of the quadratus lumborum (QL) muscle in the fascia lumborum ( Fig. 17.3 ).

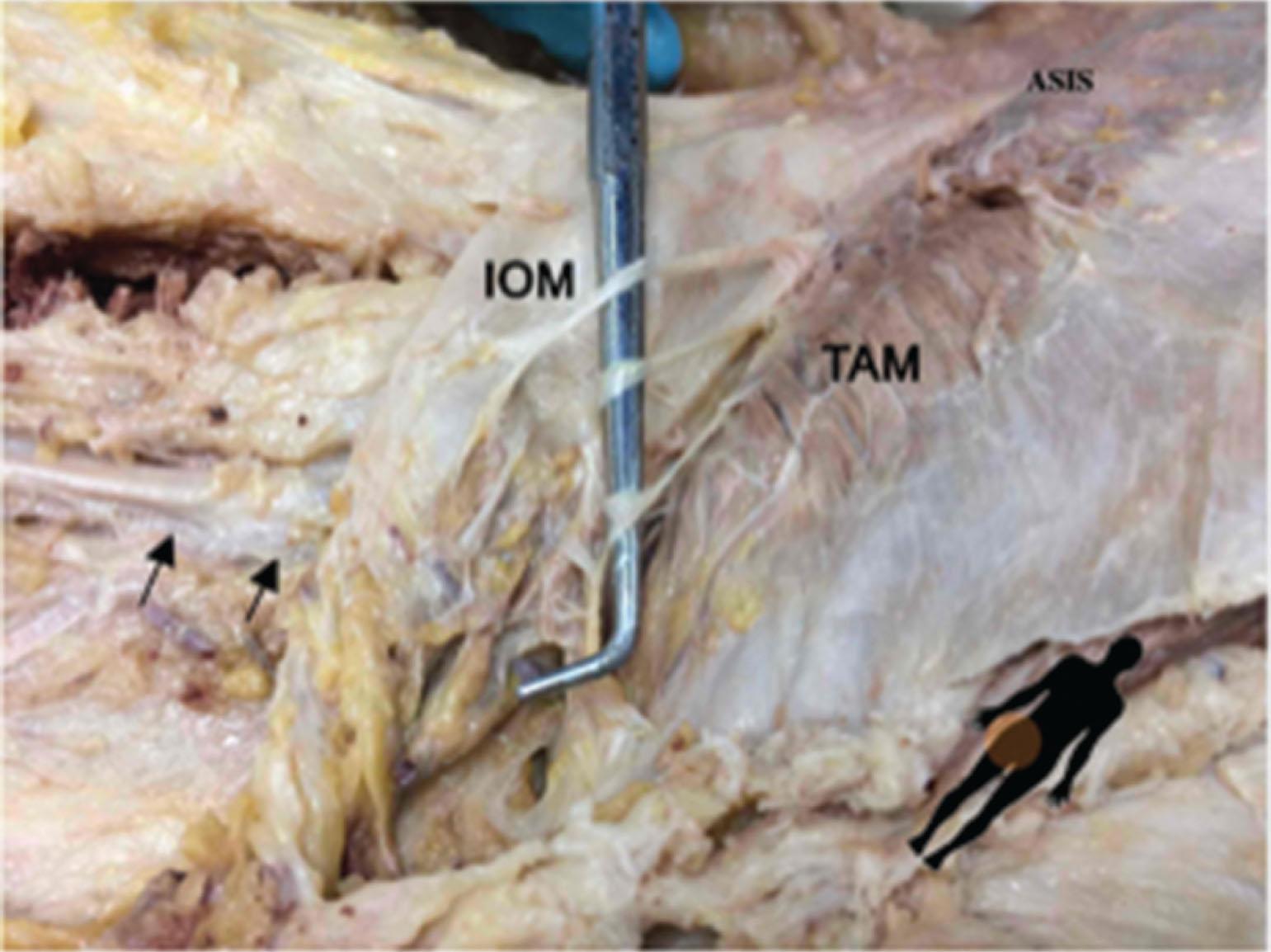

The IHN is more superior and less oblique on its course and larger in size than IIN, though their sizes many be reciprocal (i.e., if the IIN is larger, the IHN will be smaller). Halfway between the twelfth rib and the iliac crest, the IHN pierces through the transversus abdominis muscle and travels between the transversus abdominis and the internal oblique muscle towards the ASIS ( Fig. 17.3 ). Near the iliac crest, it divides into two branches. The lateral cutaneous branch of the IHN, which pierces through the internal and then the external oblique muscle just above the iliac crest, gives off the cutaneous branches to innervate skin the lateral gluteal region. The anterior cutaneous branch (often referred to as the hypogastric nerve) continues onwards between the transversus abdominis muscle and the internal oblique parallel to the inguinal ligament (IL) ( Fig. 17.4 ). It pierces the internal oblique muscle, and approximately 2 to 3 cm medial to the ASIS becomes subcutaneous by piercing the external oblique’s aponeurosis, and innervates skin of the hypogastric region just above the skin area of the IL. On its course, it gives off motor branches to the internal oblique muscle and to the distal part of transversus abdominis muscle.

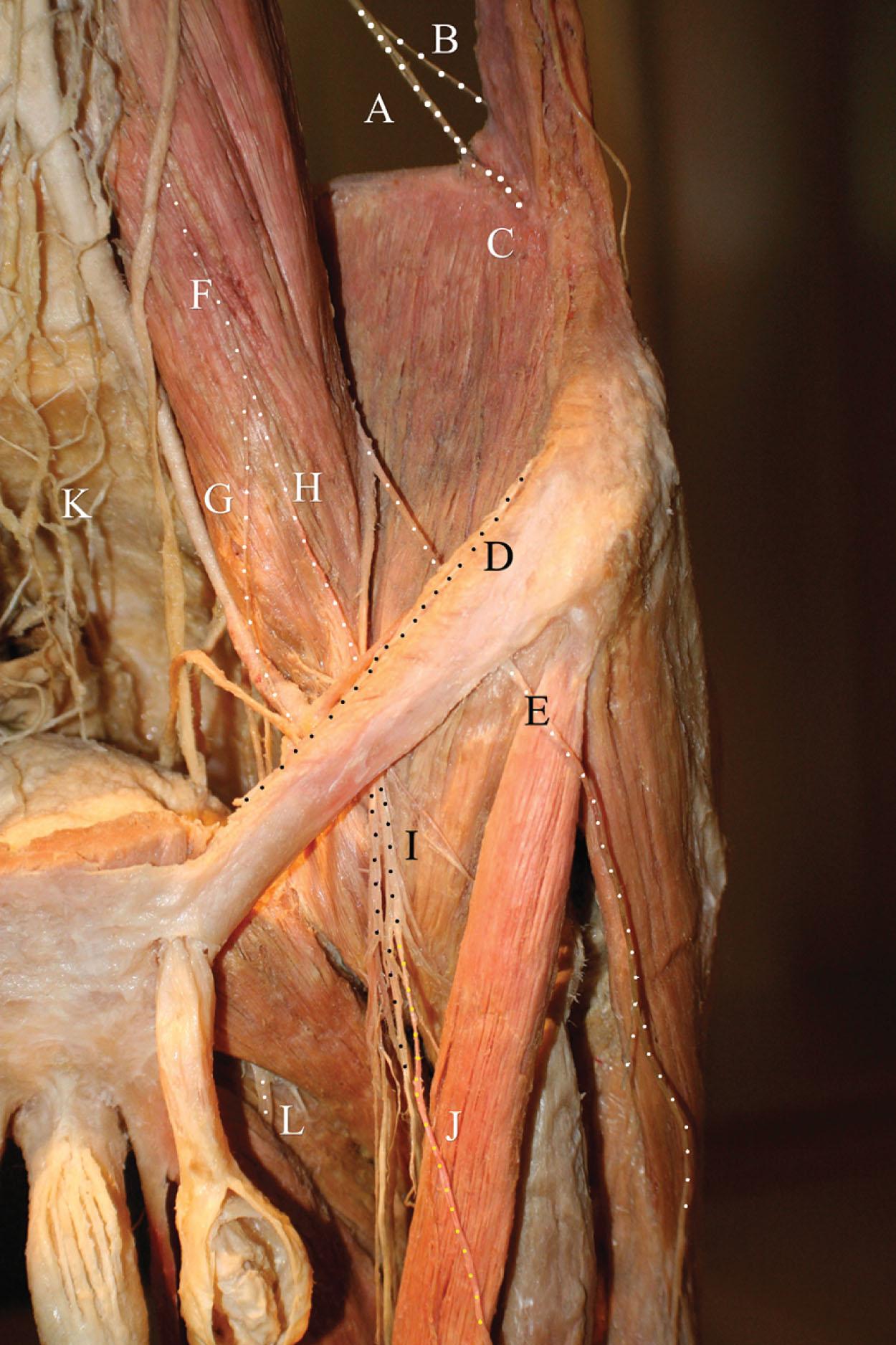

The IIN emerges on the lateral edges of the psoas major muscle inferior to the IHN and passes obliquely in front of the QL and iliacus muscle toward the iliac crest ( Fig. 17.3 ). Near the iliac crest, it perforates the transversus abdominis muscle and communicates with the IHN in the plane between the transversus abdominis and the internal oblique muscle ( Fig. 17.4 ). Then, it pierces the internal oblique muscle, enters the inguinal canal, and runs anteriorly to the spermatic cord in males or accompanies the round ligament in females ( Fig. 17.5 ). The nerve passes partly through the inguinal canal and becomes superficial by passing through the superficial inguinal ring. It branches to femoral and genital branches and innervate the skin of the upper anteromedial part of the thigh and in male the skin of the root of the penis and the anterosuperior part of the scrotum (the anterior scrotal nerve). In females, it innervates the skin of the mons pubis and labia majora (the anterior labial nerve). On its course, it gives motor branches to the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscle.

Anatomic variations are well described among the bordering nerves. There is often a reciprocal size difference between the IHN and the IIN (if one is large, it provides the majority of the innervation, and then the other is small or entirely absent), as well as between the IIN and the genitofemoral nerve (GFN) (one or the other, and sometimes both, provide innervation of the pubic region).

The cornerstones of the diagnosis are the history, physical examination, and diagnostic blocks.

The typical history includes a surgery such as a hernia repair via endoscopic or open surgery, or abdominal surgeries via a Pfannenstiel incision. Burning or stabbing pain in the inguinal region along the sensory distribution of the nerve with impaired sensation (hypoesthesia or hyperesthesia) is suspicious to entrapment neuropathy, which can be confirmed with ultrasound (US)-guided diagnostic nerve blocks. Palpation tenderness along the surgical scar and approximately 2 cm medial and caudal from the ASIS are also typical ( Fig. 17.6 ).

Become a Clinical Tree membership for Full access and enjoy Unlimited articles

If you are a member. Log in here