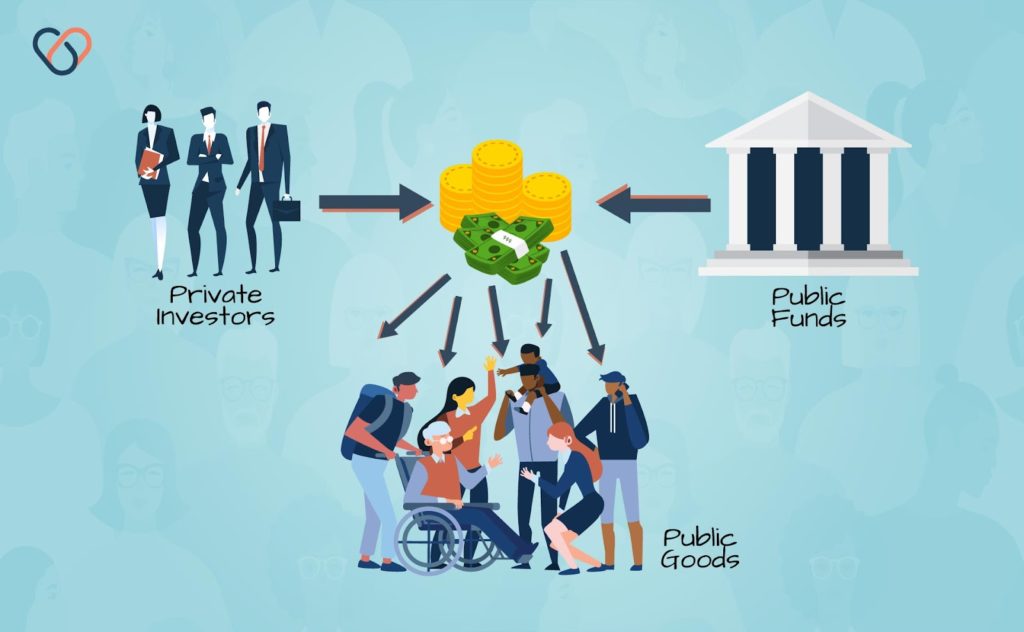

Social Impact Bonds are novel new financial models that connect private investors with larger funding sources like governments. This model allows risk-tolerant investors to provide money up-front to fund programs targeting social issues in a way that only requires risk-averse funders like governments to spent where results are seen. In other words, Social Impact Bonds shift the risk away from taxpayers onto private investors so more public goods programs can be funded with greater confidence.

Highlights

- The need for social impact bonds

- How social impact bonds address market failures

- Social impact bond stakeholders

- Differences between Bonds, Impact Bonds, and Social Impact Bonds

- An example of a successful SIB

- A brief history of SIBs

Introduction

Social Impact Bonds are a form of outcomes-based contracting involving investors who only make money when a program is successful. In this model, large payers like governments pay returns to investors based on outcome measures of a social program. Outcome measures are simply how a program’s success rate is measured—a more successful program means greater profit to investors.

The term Social Impact Bond is loosely defined and often used interchangeably with terms like social benefit bond, pay-for-success financing, or social bond. Additionally, terms like impact bond, development impact bond, and impact investing are often used to describe similar funding programs. Each of these terms is closely related and often distinguished only by the intent of the underlying program.

For example, the model by which a program seeking to improve education resources would likely be called a social impact bond. However, a program seeking to repurpose off-patent drugs might be discussed as a pay-for-success model. In either case, the underlying concept of shifting risk from a large risk-averse payer onto smaller risk-tolerant investors is the same.

Even the most impactful service programs—those designed to tackle the most concerning of social issues like hunger, equality, and homelessness—were unproven at some point. For such programs with unknown effectiveness, large funding sources such as Cities, States, or Countries have difficulty justifying investing taxpayer funds. Regardless of the intent of such programs, their unproven track record makes them much riskier investments than other programs.

Let’s be clear—spending taxpayer money to fund social programs is a form of investing. By investing in programs that address health, a government can lower healthcare expenses, thus saving money. In more traditional investment terms, lowering the cost of a program without marginalizing output is like lowering the cost basis of an investment.

For example, If a government were to invest $150M in a program that reduced healthcare costs by $200M that investment would have paid a return of $50M. This type of perspective on investing is relevant across many areas including housing, education, environmental, and many others—all sectors where social impact bonds are being used today.

For issues of less concern, like education programs for underserved communities, repurposing off-patent drugs, or job placement programs there is only sparse philanthropic funding available. This is where social impact bonds come to the rescue. Traditionally, one would seek philanthropic funds—donations. This model is only effective for those issues of most prominent concern and notoriously ineffective at scale. Social impact bonds allow the market to dictate which programs deserve funding—leaving politics out of making social improvements.

Another problem with traditional funding programs is their reliance on outdated technology and scientific understanding. Technologies like machine learning, human interface devices, and personalized healthcare stand to revolutionize all aspects of society. However, these technologies become available much faster than many social programs using them can be validated through traditional funding routes. In other words, governments can’t justify spending taxpayer money on new technology until it’s been proven to work. Unfortunately, by the time technology has been proven enough to assure political funding it’s already outdated.

We’ve discussed the basic function of social impact bonds—bringing together public and private investors to fund public goods in a much more scalable way. We’ve also discussed the stakeholders involved in a simple example of a social impact bond—payers, investors, and service providers. We’ve also discussed how the investors receive payment based on outcome measures describing a program’s success. To better understand social impact bonds let us now consider how traditional bonds work, what impact bonds are, and how both are related to social impact bonds.

What are Bonds

Bonds are a legal contract between a lender and borrower in which a fixed income is paid in return for the money. This income is typically paid as interest payments over a fixed period of time after which the bond is considered to have matured and the principle is returned to the investor.

For example, United States Treasury Bonds are issued for terms of 20 or 30 years. A purchaser of a treasury bond is loaning the United States Government money for a period of time during which they receive interest payments in return. At the end of the issuance period—when the bond matures—the US Government repays the purchaser their capital. The purchaser of a bond can also sell the bond to another party before the maturation date.

In many regards bonds are like loans—one party agrees to give another party money in exchange for interest payments. One main difference in bonds vs. loans is that bonds are tradable. This provides investors with greater liquidity such that they could sell their bonds on the open market before the maturation date if the capital was needed elsewhere. Sure, loans can be bought and sold but the market is much smaller—generally reserved for institutional investors like banks.

What are Impact Bonds

Impact bonds are much like bonds in that there is a contract between two or more parties. However, impact bonds only pay returns to investors when certain conditions are met—called outcome payments. Impact bonds can be referred to as outcome-based contracts, sometimes also referred to as pay-for-success contracts. In contrast to regular bonds, this allows one party to agree to pay another party only when the investment is guaranteed to be profitable. Sounds too good to be true, right?

Impact bonds provide a mechanism by which risk-averse entities like Governments or large healthcare providers can make riskier investments. They do this by shifting risk to another player—investors. Impact bonds secure an investment from a Success Payer with the condition that certain performance measures must be met before that bond “matures.” These conditions might be a specific percentage reduction in crime rates, greater adoption of green energy measures, or even a percentage of efficacy from an off-patent drug compared to a more expensive one.

In any case, investors then provide funds for immediate use with the guarantee that successful outcome measures will trigger the payer to release the funds secured by the impact bond—thus giving them a return on investment (ROI). Impact bonds are also different from traditional bonds in that they are not able to be traded. With this in mind, it can be easier to think of impact bonds simply as a contract. Let’s consider each role played here for a better understanding.

Social impact bonds are impact bonds designed specifically to impact social change. One would certainly be within bounds to refer to a social impact bond simply as an impact bond. The added connotation is expressed mostly to simplify discussions of outcome measures. For example, the success rate of repurposing off-patent drugs is likely to be different than those of reducing homelessness in a major metro area—two separate classes of problems.

Additionally, social impact bonds imply some degree of concern for the public good. That is, an impact bond to reduce homelessness might simply relocate a homeless population from one city to another area whereas a social impact bond would likely attempt to improve the economic conditions of that population to reduce the incident rate of homelessness. The same outcome measure—the number of homeless persons in an area—could measure both. However, the reality of the effectual outcome would be vastly different—lives having been improved vs. persons having been located.

Stakeholders

The power of impact bonds is realized through cooperation and agreement among several different stakeholders. This is just a fancy term that refers to someone who has an interest in something. Impact bonds bring together many different stakeholders in a way that transcends the limitations of traditional fundraising.

Rather than relying on stakeholder philanthropic spirit, social impact bonds use a model that leverages the free market. Below is a brief discussion of how each primary type of stakeholder is incentivized to participate in the social impact bond model. Many different types of individuals or organizations can be considered any one of these, based on their role in a particular SIB.

Success Payers

A Success Payer (a.k.a. Commissioner) is someone who provides a conditional bond. Entities like Cities, States, and Governments are common examples of Success Payers in Impact Bonds. The payer is a relatively risk-averse party that has a relatively large amount of capital. Traditionally, this risk-aversion prevents such a payer from investing their money in programs where there is a higher degree of uncertainty in the outcome.

Impact bonds allow Success Payers to invest in risky endeavors by guaranteeing they will only pay when an outcome is successful. Imagine being able to tell a stockbroker you wanted to invest your savings into the stock market—but only if the stock market went up. That’s a promise impact bonds can make and why they are such powerful tools for raising capital from large, risk-averse Success Payers like Governments. In this way, social impact bonds incentivize Success Payers by eliminating their risk. Examples of social impact bond Success Payers may include Local, State, and Federal governments. In some cases, Non-Profit organizations or large philanthropic funds may also act as payers.

Investors

The investor is someone who is more risk-tolerant and willing to allocate their funds to programs, research initiatives, or new social programs where outcomes are more uncertain. The impact bond investor immediate capital to an initiative to pursue the programs outlined by impact bonds. While outcome measures are not certain, impact bonds provide a unique way for investors to earn money from large low-risk investors like Governments.

In this way, investors are incentivized to participate because social impact bonds offer novel new investment opportunities previously unavailable. Common examples of social impact bond investors include retail investors, hedge funds, and sometimes even smaller government bodies like Cities.

Service Providers

Service providers are needed for impact bonds for many reasons. In the most basic of cases, service providers include the parties that execute the program designed to exact change, evaluate the success of the program, and negotiate the contract between the payer and investors.

Service providers are third parties without conflicting interests in the conditions of an impact bond. For example, an investor would make a poor evaluator because there would be an incentive for them to record more favorable outcomes that produce the highest payout to them. Service providers are incentivized by social impact bonds just as they are by any other contract—by the opportunity to make money.

A wide range of stakeholders may be considered service providers. Among the most integral is the Evaluator—the party responsible for evaluating outcome measures of the program a social impact bond has funded. This stakeholder is responsible for measuring the success of the program which dictates the amount of payout investors receive. Other examples of service providers include program administrators, contract negotiators, or contract research organizations.

Society

The defining characteristic of social impact bonds is their focus on financing public goods for the benefit of society. Smaller programs may do this by focusing on making an impact in local communities while larger funds might aspire to make broader, sometimes even international, improvements. Social impact bonds are designed in such a way to benefit all stakeholders in a way that actively incentivizes their participation.

Monetary incentivization is clear among Commissioners, Investors, and Service providers but isn’t entirely accurate for the incentive for Society to accept the SIB. Rather than money, the incentive for local, state, and federal governments to accept, support, and embrace social impact bonds is the understanding that SIBs intention is to improve society in a way that benefits all.

Social impact bonds have been developed, administered, and completed across the globe over the past decade. These programs have targeted many areas of specific concern including health, education, homelessness, and more. Detailed information on these programs is available from the Government Outcomes Lab website. Below, we’ll take a look at a few examples of specific programs that illustrate the design, outcomes, and benefit that social impact bonds can provide.

United Kingdom’s ONE Service SIB

In 2010, the UK Ministry of Justice Commissioned the World’s first social impact bond intent to lower recidivism rates among short-term offenders in the Petersborough detention system. This bond funded the ONE Service, an organization with the mission of providing service to prisoners exiting the Peterborough facility.

This project was funded by a number of investors including the Barrow Cadbury Charitable Trust, The Henry Smith Charity, the Tudor Trust, and the Paul Hamlyn Foundation. The program was designed to run for 7 years with outcome payments realized starting at a 7.5 percent reduction in recidivism. The RAND Corporation was tasked as the evaluator to determine the extent to which investors would receive a return based on outcome measures. The program was cut short due to legislative changes but showed a 9 percent decrease in recidivism marking a resounding proof-of-model.

This program resulting exceed the bond measurement requirements, realizing a 9% reduction in reincarceration rates. While missing the early payment requirements, investors saw a 3% yearly return—nearly 300% greater than that of most U.S. Treasury bonds! Since this pilot model, there have been more than 130 social impact bonds launched globally representing nearly half a billion dollars in allocated capital!

New York City’s Adolescent Behavioral Learning Experience (ABLE) Program

New York City commissioned a social impact bond in 2012 with the goal of reducing recidivism among 16 to 18-year-olds held at the Rikers Island facility. This program was the first initiative in the United States that was funded using social impact bonds.

The initiative was financed by Goldman Sachs, an investment bank, with their investment being reimbursed starting at a reduction in recidivism by 10% and returns on their investment starting at a drop of 11 percent. This program was evaluated by the VERA Institute of Justice which, unfortunately, found that the program was unsuccessful that led to its discontinuation in 2015.

Finland’s Integration SIB Project

In 2016, the Finnish Government launched the Integration SIB project, funded by a social impact bond, to help immigrants find employment as quickly as possible. The program’s goals were to find 2,000-2,500 immigrants jobs within a three-year period.

This SIB was commissioned by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment (a.k.a. The Payer) and funded by the European Investment Fund, Sitra, the City of Espoo, the Orthodox Church of Finland, and several others for a total of €14.2MM. Epiqus Oy was selected to manage this SIB program which included providing education, training, and job placement services.

Social impact bonds are new. Given the first SIB was commissioned in 2010 there’s no surprise that many implementations are still in somewhat of a discovery phase. In other words; the world is still figuring out how SIBs might fit into different industries. Healthcare and drug development are two such industries in which social impact bonds are being tapped to help innovate new solutions to tough problems.

In 2016, Dr. Bruce Bloom of Cures Within Reach published a paper titled Repurposing Social Impact Bonds for Medicine in which he made the case for—as the title suggests—using SIBs to fund medicine-related endeavors. The general thesis of the paper is that the existing patent system overly-incentivize research on using new drugs to treat disease while ignoring the potential of thousands of existing therapies.

In his article, Bloom estimates that new drugs take 10-15 years and as much as $3 billion to develop. By contrast, Bloom also describes a successful drug repurposing trial for the treatment of an autoimmune condition as having been completed in only 36 months and for only $500,000. The article then goes on to offer social impact bonds, also known as Pay-for-Success contracts, as a viable mechanism by which drug repurposing trials could be funded. In this regard, Bloom’s suggestion seems to offer a viable alternative to the current patent system.

Final Thoughts

Social impact bonds have seen a sharp rise in interest since the launch of the UK’s ONE program. Since then, nearly half a billion dollars has been raised worldwide. While this number pales in comparison to charitable funding efforts it marks a novel new means by which for-profit investors are incentivized to invest in programs traditionally attractive only to charitable giving.

The stakeholders outlined here each play a vital role in ensuring the success of social impact bonds. While success payers are essential in creating a market for investors—without dedicated administrators and services providers the system won’t work. This latter consideration inspires Crowd Funded Cure’s mission to continue developing Pay-for-Success contracts that can be implemented quickly, efficiently, and in a permissionless fashion on the blockchain.

As noted by Dr. Bloom, the application of social impact bonds in healthcare and medicine has strong potential. By introducing an alternative financing mechanism into the market of drug development, existing off-patent, nutraceutical, and otherwise un-patentable therapies can be quickly and affordably put into action to treat any number of health conditions. Whether compounds are used to treat emerging threats such as COVID-19 or existing diseases for which there is little funding—social impact bonds will play a vital role in how they are funded.