Pelham Bay Park

| Pelham Bay Park | |

|---|---|

Northern tip of Hunter Island in Pelham Bay Park | |

| |

| Type | Municipal |

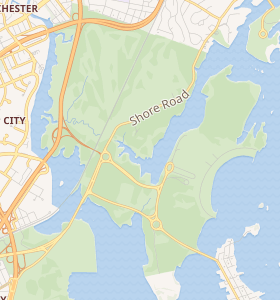

| Location | The Bronx, New York, US |

| Coordinates | 40°51′56″N 73°48′30″W / 40.86556°N 73.80833°W |

| Area | 2,772 acres (1,122 ha)[a] |

| Created | 1888 |

| Operated by | New York City Department of Parks and Recreation |

| Public transit access | Subway: Pelham Bay Park ( MTA New York City Bus: Bx29 Bee-Line Bus: 45 |

Pelham Bay Park is a municipal park located in the northeast corner of the New York City borough of the Bronx. It is, at 2,772 acres (1,122 ha),[a] the largest public park in New York City. The park is more than three times the size of Manhattan's Central Park. The park is operated by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation (NYC Parks).

Pelham Bay Park contains many geographical features, both natural and man-made. The park includes several peninsulas, including Rodman's Neck, Tallapoosa Point, and the former Hunter and Twin Islands. A lagoon runs through the center of Pelham Bay Park, and Eastchester Bay splits the southwestern corner from the rest of the park. There are also several recreational areas within the park. Orchard Beach runs along Pelham Bay on the park's eastern shore. Two golf courses and various nature trails are located within the park's central section. Other landmarks include the Bartow-Pell Mansion, a city landmark, as well as the Bronx Victory Column & Memorial Grove.

Before its creation, the land comprising the current Pelham Bay Park was part of Anne Hutchinson's short-lived dissident colony. Part of New Netherland, it was destroyed in 1643 by a Siwanoy attack in reprisal for the unrelated massacres carried out under Willem Kieft's direction of the Dutch West India Company's New Amsterdam colony. In 1654 an Englishman named Thomas Pell purchased 50,000 acres (20,000 ha) from the Siwanoy, land which would become known as Pelham Manor after Charles II's 1666 charter. During the American Revolutionary War, the land was a buffer between British-held New York City and rebel-held Westchester, serving as the site of the Battle of Pell's Point, where Massachusetts militia hiding behind stone walls (still visible at one of the park's golf courses) stopped a British advance.

The park was created in 1888, under the auspices of the Bronx Parks Department, largely inspired by the vision of John Mullaly, and passed to New York City when the part of the Bronx east of the Bronx River was annexed to the city in 1895. Orchard Beach, one of the city's most popular, was created through the efforts of Robert Moses in the 1930s.

History

Pre-colonial times

Before the colonization of what is now New York State in the 17th century, Pelham Bay Park comprised an archipelago of islands separated by salt marshes and peninsular beaches.[6] Geologically, most of the park's land first formed during the end of the last ice age, the Wisconsin glaciation, which occurred 10,000 to 15,000 years before the first colonists arrived. The melting of the glaciers caused the formation of the current marshes. Sea level rise from the melting glaciers caused sedimentation along the shore, creating sand and mud flats. Gradually, saltwater cordgrass started to retain sediment, causing some of the inland marshes to flood only during high tide.[7]

The Siwanoy (transliterated as "southern people") were the first Native American tribe to inhabit the Long Island Sound's northern shoreline east to Connecticut. They lived a mostly hunter-gatherer existence.[8][9] The Siwanoy used the modern-day park site as a ceremonial and burial site, as evidenced by the wampum belts found in the area,[10] which were used for diplomatic purposes among local Native American tribes.[11] Two glacial erratics in the park, deposited during the end of the last ice age, were used ceremonially by the Siwanoy: the "Gray Mare" on Hunter Island, and Mishow near the Theodore Kazimiroff Nature Trail.[8]

17th and 18th centuries

The Dutch West India Company purchased the land in 1639.[11] They called it Vreedelandt, which roughly translates to "land of freedom",[9][12] and alternatively Oostdorp, meaning "east village".[12] Oostdorp became the area known as Westchester Square, to the southwest of the current park.[13][14]

In 1642, Anne Hutchinson and her family moved from Rhode Island to Split Rock, along the Hutchinson River in what is now Pelham Bay Park. Although the family was English, the land was part of New Netherland under Dutch authority.[15] The exact location of the Hutchinson house is unknown, with one scholar saying that the house was in the modern-day park on the east side of the Hutchinson River,[16]: 231 and another saying that the house was on the west side of the river in now Baychester.[17] The Siwanoy destroyed the Hutchinson settlement and killed the family in August 1643,[16]: 239 [18] in reprisal for the unrelated massacres carried out under Willem Kieft's direction of the Dutch West India Company's New Amsterdam colony.[19][16]: 237 [15]

In 1654 an Englishman named Thomas Pell purchased 50,000 acres (20,000 ha) from the Siwanoy, comprising the land of the current Pelham Bay Park as well as the nearby town of Pelham, New York, and made his estate on 9,188 acres (3,718 ha) of that land.[20][21] The current park consists of the southernmost portion of Pell's estate, excluding Hart Island and City Island.[22] Pell's land became known as Pelham Manor after Charles II's 1666 charter,[21][23] and parts of Pell's land claim were in conflict with that of other nearby settlers.[13] Pell died in 1669, willing his property to his nephew John,[13][24] who sold off City Island in 1685.[13] The land grant was renewed in 1687.[21] The next year, Jacob Leisler bought 6,000 acres (2,400 ha) of the remaining property on behalf of the Huguenots, and with that land, founded the town of New Rochelle for the Huguenots.[13][22] Upon John Pell's death in 1700, he willed the property to his son Joseph, who in turn transferred ownership to his own son, John. Ownership of the manor then went to the Bartow family,[25] who were maternal descendants of the Pell family.[12] The Pell family burial plot faced the Pelham Bay waterfront on the eastern side of the manor.[26][27]

The land was the site of the Battle of Pell's Point during the American Revolutionary War.[28] After the British forces unsuccessfully attempted to trap the main body of the Continental Army on the island of Manhattan, British Army commander-in-chief General Sir William Howe looked for another location along Long Island Sound to disembark his troops.[29]: 246, 255 On October 18, 1776, he landed 4,000 men at Pelham, close to the current park.[30]: 5 A brigade of 750 men under the command of the American Colonel John Glover were already inland, and they attacked the British advance units from behind a series of stone walls.[30]: 14–17 After a series of attacks, the British broke off, and the Americans retreated.[29]: 255 [20][31]

In 1836, Robert Bartow, a descendant of Thomas Pell,[3] bought 30 acres (12 ha) of his ancestor's old estate. By 1842, construction was complete on the Bartow-Pell Mansion, the family's manor.[32] Bartow died in 1868, and his family sold the mansion to the city in 1880.[32] The mansion went maintained until 1914, when the city and International Garden Club assumed joint maintenance of the building.[32][33]

1870s and 1880s: Creation

In the 1870s, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted envisioned a greenbelt across the Bronx, consisting of parks and parkways that would align more with existing geography than a grid system similar to the Commissioners' Plan of 1811 in Manhattan. That grid had given rise to Central Park, a park with mostly artificial features within the bounds of the grid.[34][35] However, in 1877, the city declined to act upon his plan.[36] Around the same time, New York Herald editor John Mullaly pushed for the creation of parks in New York City, particularly lauding the Van Cortlandt and Pell families' properties in the western and eastern Bronx respectively. He formed the New York Park Association in November 1881.[37][38] There were objections to the system, which would apparently be too far from Manhattan, in addition to precluding development on the site.[39][40] However, newspapers and prominent lobbyists, who supported such a park system, were able to petition the bill into the New York State Senate, and later, the New York State Assembly (the legislature's lower house).[41][42] In June 1884, Governor Grover Cleveland signed the New Parks Act into law, authorizing the creation of the park system.[41][43][40][44]

Legal disputes carried on for years. Opponents argued that building a park system would divert funds from more important infrastructure, and that everyone in the city would need to pay taxes to pay for the parks' construction, regardless of whether they lived near the parks. In particular, Pelham Bay Park was located within Westchester County at the time, out of city limits.[45] The city was reluctant to pay to buy the parkland because of the cost and locations.[46] Supporters argued that the parks were for the benefit of all the city's citizens; that the value of properties near the parks would appreciate greatly over time; that the Pelham Bay Park site could easily be converted into a park; and that Pelham Bay Park would soon be annexed to the city. Ultimately, the parks were established, owing to efforts from supporters.[45]

After much litigation, the city acquired the land for the park.[46] Although the residents of Pelham had initially supported the park's creation, they came to oppose it when they found that the park's creation would decrease the town's tax revenue.[47] The 1,700 acres of land for the park were part of the town's 3,000-acre (1,200 ha) area at that time, but could not be taxed, nearly halving the town's tax revenues from land area. One Pelham resident's letter to New York City Mayor Abram Hewitt, asking for financial assistance to supplement the town's growing tax rate, was published in The New York Times in February 1887.[48] A month later, a group of Pelham residents petitioned Hewitt to oppose the park plan.[49][47] The government of New York City also did not want to pay taxes to the town of Pelham if it bought the land for the park, which had been one of the reasons for its initial opposition to acquiring the land.[50] There was a proposal to have New York City pay taxes to Pelham if it acquired the land, which the city's Tax Department called "entirely novel, and of course, wrong".[51]

Despite Pelham residents' opposition to the park, the city acquired the land for Pelham Bay Park in 1887, and it officially became a park in 1888.[52]: 693 [46] Pelham Bay Park became a recreation area under the auspices of the Bronx Parks Department,[53] which bought the land for $2,746,688, equivalent to $93,143,242 in 2023.[9] The park used land from multiple estates spread out over an excess of 1,700 acres (690 ha).[9][46][54] Some of the old estates' mansions were still standing twenty years later.[55] To alleviate the concerns of Westchester property owners who lost land during the park system's acquisition, the New York City Commissioners of Estimate distributed compensation payments.[52]: 694 The Commissioners of Estimate paid a combined $9 million (equivalent to $305,200,000 in 2023), but some land owners sued for more compensation in 1889.[56]

1890s to 1920s: Early years

In 1890, Mullaly proposed using the site for the 1893 World's Fair due to its size;[57] however, the fair was eventually awarded to Chicago instead.[58] The Pell family's burial vault was also marked for preservation that year,[59]: 34 (PDF p.135) and in July 1891, the descendants of the Pell family were given permission to maintain and restore the plot.[60]: 70 (PDF p.128) After the park opened, several individuals were allowed to reside in the mansions within the park. In 1892, the New York City Department of Public Parks separately allowed the occupation of the Hunter, Hoyt, and Twin Island houses.[61]: 9 (PDF p.67), 32 (PDF p.89), 109 (PDF p.193) The next year, two buildings near Pelham Bridge were auctioned off.[62]: 404 (PDF p.471)

Pelham Bay Park's ownership was passed to New York City when the part of the Bronx east of the Bronx River was annexed to the city in 1895.[54] Despite the park being for public use, some of the old estates remained standing, with a few occupied by private families. Due to its distance from the city, NYC Parks decided to keep 3,000 acres (1,200 ha) of Pelham Bay and Van Cortlandt Parks in their natural state, unlike some of the other parks closer to Manhattan, which were being extensively landscaped.[63]: PDF pp.442–443 None of the houses were rented in 1899,[64]: 23 but by 1900, thirty-six houses in the park were being used as private residences, comprising 75% of houses rented within parks in the Bronx.[65]: 20 This number dropped to thirty-three the next year.[66]: 65

In spring 1902, NYC Parks destroyed two houses in the park and used the remaining wood to build free bathhouses, which were used by about 700 bathers per day during that summer.[67]: 116 (PDF p.85) Around 1903, Hunter Island became a popular summer vacation destination.[68][69] Due to overcrowding on Hunter Island, NYC Parks opened a campsite two years later at Rodman's Neck on the south tip of the island, with 100 bathhouses.[69][46][54][70] Orchard Beach, at the time a tiny recreational area on the northeast tip of Rodman's Neck,[71] was expanded that year.[70] In 1904, an athletic field was opened within Pelham Bay Park.[72]

By 1917, Hunter Island saw half a million seasonal visitors.[69] Orchard Beach also became popular, with an average of 2,000 visitors on summer weekdays and 5,000 visitors on summer weekends in 1912.[46] However, the park's condition started to decline in the 1920s as the surrounding areas were developed. The park facilities were dirty and deteriorating due to overuse, and there was a lot of vandalism.[46][54] Hunter Island was closed and camping was banned, so some park patrons began camping illegally.[73]

1930s-1960s: Moses renovation projects

The current Orchard Beach recreational area and Split Rock golf course was created through the efforts of New York City park commissioner Robert Moses.[74][3][75] Immediately after assuming his position in 1934, Moses ordered engineers to inventory every park in the city to see what needed renovating.[76] He devised plans for a new Orchard Beach recreation area after he saw the popularity of the Hunter Island campsite.[69] On February 11, 1934, Moses announced a plan for the new golf course.[74] Two weeks later, he announced another plan for the upgraded beach, which had been inspired by the design of Jones Beach on Long Island.[77] The beach and existing golf course would be reconstructed through the Works Progress Administration (WPA) under the 1930s New Deal program.[3][78][74][79]

Moses canceled 625 leases for the project, and after campers unsuccessfully sued the city,[80] the site was cleared of campers in June.[81] Moses decided to connect Hunter Island and the Twin Islands to Rodman's Neck by filling in most of LeRoy's Bay.[71] The deteriorated Hunter Mansion was demolished with the construction of the beach.[82] The golf courses were reopened in June 1935, sixteen months after construction commenced. John van Kleek designed the brand-new Split Rock golf course as part of the city's program to upgrade or build ten golf courses around the city.[83][84]

A final design for the beach was unveiled in July 1935.[85][86][87] The beach project involved filling in approximately 110 acres (45 ha) of LeRoy's and Pelham Bays with landfill,[3] followed by a total of 4,000,000 cubic yards (3,100,000 m3) of sand.[88][89] Moses thought that waste from the New York City Department of Sanitation would be cheaper than sand.[88] In early 1935, workers began placing the garbage fill[90] around Rodman's Neck, Twin Island, and Hunter Island.[90][91] After the garbage began washing onto the beach, the rest of the site was filled-in using sand starting in 1936.[88][92] The beach, designed by Gilmore David Clarke and Aymar Embury II, was dedicated in July 1936[75][91] despite only being partially complete.[93][94] The beach officially opened on June 25, 1937.[95] Soon after Orchard Beach opened, it was expanded, starting with the southern locker room in 1939.[96][97] The water between Hunter and Twin Islands was filled in during 1946 and 1947, with new jetties at each end of the beach. The promenade was extended over the fill and opened in 1947,[98][73][69][99] Further improvements were made to the bathhouse pavilion in 1952 and to the northern jetty in 1955. A new concession stand was added north of the pavilion in 1962,[98] and a privately funded Golf driving range was also added that year.[100] The beach was renovated starting in 1964.[101]

In 1959, after the Rodman's Neck section of the park had been used for various purposes, the New York City Police Department used land from the park to create the Rodman's Neck Firing Range at the southern tip of the peninsula. Previously, the parkland at Rodman's Neck had been underused, with the NYPD and United States Army using the land at various times.[102][103]

1960s-present: Cleanup and restoration

The City began landfill operations on Tallapoosa Point in Pelham Bay Park in 1963.[104][105] Plans to expand the landfills in Pelham Bay Park in 1966, which would have created the City's second-largest refuse disposal site next to Fresh Kills in Staten Island, were met with widespread community opposition.[104] The landfill expansion was seen as a way to alleviate the city's accumulations of waste, and Tallapoosa was seen as the only suitable location to put the landfill.[106] The preservation effort was headed by Dr. Theodore Kazimiroff, a Bronx historian and head of The Bronx County Historical Society. It suffered setbacks in August 1967 when the New York City Board of Estimate voted against an initial effort to create to protected area in the proposed landfill expansion site.[107][108] However, the state and federal governments did not favor the landfill being located at Tallapoosa.[109] In October, Mayor John Lindsay signed a law authorizing in the creation of two wildlife refuges, the Thomas Pell Wildlife Sanctuary and the Hunter Island Marine Zoology and Geology Sanctuary, on the site where the landfill was planned to be expanded.[104] Tallapoosa West continued to be used as a landfill until May 1968, when the landfill permit was revoked.[106] In November of that year, Tallapoosa West was made a part of the Pell refuge.[110] The dump was still operating as late as 1975, when the garbage there was described as being ten stories high.[111] The landfill closed in 1978.[105] However, a report published in 1983 claimed that the Tallapoosa landfill, as well as five others throughout the city, was heavily contaminated with "toxic wastes" dumped from 1964 to 1979.[112][113] The waste from the landfill reportedly led to health problems for residents of nearby communities such as Country Club. The Tallapoosa landfill at Pelham Bay Park was designated a hazardous-waste site in 1988, and cleanup began in 1989.[105]

In 1983, the Theodore Kazimiroff Environmental Center was proposed for the park, alongside a nature trail that would wind through the park's terrain.[114] It would be named out of respect to the late historian,[114] who had died in 1980.[115] The Kazimiroff Nature Trail and the Pelham Bay Park Environmental Center opened in June 1986.[116][115][73] A $1 million renovation of the Orchard Beach pavilions (equivalent to $2,780,000 in 2023) was completed by 1986.[117] By the end of the decade, large numbers of human and animal remains were being dumped in Pelham Bay Park, including 65 human bodies that were dumped in the park from 1986 to 1995. Pelham Bay Park was also very dirty, and discarded trash from several decades prior was still visible.[118] NYPD officers on these cases theorized that the frequency of body dumpings might be attributable to two things: the park's remote location near highways, as well as a belief that the parkland is haunted by the remains of the Siwanoy buried there.[119]

In 1990, NYC Parks received a $6.3 million gift for improvements to Pelham Bay Park and twenty other parks around the city. NYC Parks used the money to renovate trails and clean up weeds.[120] A renovation of Orchard Beach started in 1995.[121] A water park for the beach was proposed, but ultimately canceled in 1999.[122] A few years later, as part of the city's ultimately unsuccessful bid for the 2012 Summer Olympics, several facilities in Pelham Bay Park were proposed for upgrades. The new facilities would have included a shooting center at Rodman's Neck; a 350-meter (1,150 ft) horseback riding track; and a fencing, swimming, and water polo facility in the Orchard Beach pavilion.[123] The bid ultimately was awarded to London instead.[124]

In 2010, construction began on extending the jetty at Orchard Beach at a cost of $13 million.[125][126] Soon after, work started on a $2.9 million project to restore Pelham Bay Park's shoreline, which entailed renovating the seawall, adding a dog run, and creating a new walking trail.[127] In 2012, Native American shell middens were found at Tallapoosa Point, prompting an archaeological investigation.[128] Further digs at the site uncovered more than a hundred artifacts, some of which dated to the third century CE. Work on the restoration project was paused in June 2015 as a result of the finds.[127][129] The restoration project was restarted in September 2015.[130]

Geography

At 2,772 acres (1,122 ha),[a] Pelham Bay Park is the city's largest,[5][131] being slightly more than three times the size of the 843-acre (341 ha) Central Park.[132][5] Pelham Bay Park includes 13 miles (21 km) of shoreline[132] as well as land on both sides of the Hutchinson River. Hunter Island, Twin Island, and Two-Trees Island, all formerly true islands in Pelham Bay, are now connected to the mainland by fill, and are part of the park.[2] Several islands in the Long Island Sound (including the Chimney Sweeps Islands),[133] as well as Goose Island in the Hutchinson River, are also part of Pelham Bay Park.[134] The park is divided into several sections, including two main sections roughly divided by Eastchester Bay.[135][136]

In the eastern section of Pelham Bay Park is Orchard Beach and its parking lot. The eastern section also contains the Hunter Island Wildlife Sanctuary on Twin and Hunter Islands. The Kazimiroff Nature Trail winds through this section.[136] The northwestern section, divided from the eastern section via the Lagoon. It contains both golf courses, as well as the Thomas Pell Sanctuary; the Bartow-Pell Woods; Goose Creek Marsh; and the Siwanoy, Bridle, and Split Rock Trails. The park is crossed by Amtrak's Northeast Corridor railroad at this location, as well as by the Hutchinson River Parkway and New England Thruway.[136] A central section contains a Central Woodland, where the Siwanoy Trail and Turtle Cove Driving Range is present. It also includes Rodman's Neck as well as a portion of the park known as "The Meadow".[136] The Pelham Bridge carries traffic across the Eastchester Bay between the southwest section and the rest of the park.[136]

The park contains many different habitats. The largest habitat is the 782-acre (316 ha) forests, followed by the 195-acre (79 ha) salt marshes, the 161-acre (65 ha) salt flats, the 83-acre (34 ha) meadows, the 751-acre (304 ha) mixed scrub, and the 3-acre (1.2 ha) fresh water marsh.[137] In total, about 67% of the park is estimated to be in its natural state, while 33% of the park is estimated to be developed.[138]: 129 In the latter half of the 20th century, Pelham Bay Park's biodiversity decreased: in that time, the park was observed to have lost 25% of its 569 native species of plants as well as 12.5% of its 321 non-native species.[138]: 132

Land features

Hunter Island

Hunter Island (40°52′36″N 73°47′24″W / 40.876773°N 73.789866°W) is a 166-acre (67 ha) peninsula filled with woodlands; it had previously been 215 acres (87 ha) until Robert Moses extended Orchard Beach in the 1930s.[82] A former island, it was part of the Pelham Islands, the historical name for a group of islands in western Long Island Sound that once belonged to Thomas Pell. The Siwanoy referred to the island as "Laap-Ha-Wach King", or "place of stringing beads".[82][139] The island was then renamed after John Hunter, a successful businessman and politician, who purchased the property in 1804[140] and moved his family to the island in 1813.[141] They built a mansion in the English Georgian style[139][142] at the highest point on the island (90 feet above sea level).[82] The mansion was destroyed in 1937 during the construction of Orchard Beach.[82][141] In 1967, the island became part of the Hunter Island Wildlife Sanctuary.[82]

Twin Island

Twin Island, at 40°52′16″N 73°47′04″W / 40.871186°N 73.784389°W, is wooded with exposed bedrock with glacial grooves. The East and West Twin Islands (or the "Twins") were once true islands in Pelham Bay but are now connected to each other and to Orchard Beach and nearby Rodman's Neck by a landfill created in 1937.[139][143][144] East Twin Island, a rocky formation with "ribbons of color" caused by sedimentary erosion, is connected to neighboring Two Trees Island via a thin mudflat land bridge. Two Trees Island itself consists of a rocky plateau upon which one can see Orchard Beach and the environmental center.[143] West Twin Island was at one time connected to neighboring Hunter Island via a man-made stone bridge,[145][146] which now lies in ruins in one of the city's last remaining salt marshes.[147]

The two islands that are now combined as Twin Island have been owned by NYC Parks since the 1888 acquisition of Pelham Bay Park.[146] A tennis court was built on the island in 1899.[64]: 26 Twin Island was restored in 1995 as part of the Twin Islands Salt Marsh Restoration Project, which cost $850,000.[147]

Rodman's Neck

Rodman's Neck is a peninsula located in the central section of the park (at 40°51′09″N 73°48′02″W / 40.852501°N 73.800556°W). The southern third of the peninsula is used as a firing range by the New York City Police Department (NYPD); the remaining wooded section is part of Pelham Bay Park.[136][148] The north side, which is joined to the rest of Pelham Bay Park near Orchard Beach, contains several baseball fields.[136][149] Two small land berms between Rodman's Neck and City Island consist of the island's only connecting road to the mainland.[2]

Rodman's Neck was part of the historic Pell property,[150] and since the city acquired the peninsula in 1888, it has been used for multiple purposes.[103] It was used as a United States Army training location during World War I,[102] and was converted to under-utilized parkland in the 1920s.[102][103] From 1930 to 1936, the peninsula was incorporated as part of Camp Mulrooney, a summer camp for the NYPD.[102][103] The Army used Rodman's Neck again in the 1950s during the Cold War.[102] and the NYPD built the current firing range at the peninsula's southern tip in 1959.[102]

Tallapoosa Point

Tallapoosa Point is located in the southwest of Pelham Bay Park, near the Pelham Bridge.[136] It used to be a separate island south of Eastchester Bay, having been private property, but was connected to the mainland during the colonial period. The point then became a popular fishing spot.[151] In 1879, the Tallapoosa Club political group started leasing part of the peninsula from the city during the summer, hosting activities there. The club's presence gave the peninsula its current name, and in turn, the club's name was derived from Tallapoosa, Georgia, where some of its members had fought during the American Civil War.[152] The Tallapoosa Club used a mansion originally built by the Lorillard family.[153] They used the mansion until October 1, 1895.[154]: 50 (PDF p.138)

Tallapoosa Point was used as a dump from 1963[104] until 1968, when landfill operations ceased[106] and it became a part of the Wildlife Refuge.[110] Since then it has been a part of the park, but there was an obscure proposal in the 1970s to make Tallapoosa into a ski slope.[151] Tallapoosa Point was later re-planted and serves as a bird habitat.[155]

Waterways

Pelham Bay

Between City Island and Orchard Beach is a sound named Pelham Bay (40°51′59″N 73°47′25″W / 40.866335°N 73.790321°W), but contrary to its name, it is not a bay, but rather a sound since it is open to larger bodies of water at both ends. It connects to Eastchester Bay at the south, and opens onto Long Island Sound and City Island Harbor at the east.[136] Approximately one third of the original bay was filled in to create Orchard Beach from 1934 to 1938.[3]

Eastchester Bay

Eastchester Bay is a body of water that separates City Island and most of the park from the park's southwest portion and the rest of the Bronx.[136][156] It is crossed by the Pelham Bridge, which connects the two parts of the park.[156] It is technically also a sound, and the northern end connects via a narrow channel to Pelham Bay. The Hutchinson River empties into Eastchester Bay near the northern end. The lower portion of the bay opens onto the East River, Little Neck Bay, and Long Island Sound.[157]

Lagoon

A lagoon within the park was once part of Pelham Bay, separating Hunter and Twin Islands from the mainland, and was called LeRoy's Bay until the mid-20th century. It was popular for rowing regattas,[158] but could not be used for regulation rowing races as it was blocked by the causeway to Hunter Island.[159] By 1902, there were calls to remove the causeway so LeRoy's Bay could be used as a raceway.[159] The New York City Department of Public Parks decided to create a "temporary" wooden bridge and remove the causeway to allow the bay's tides to flow freely.[160]

Most of the lagoon was filled in during the mid-1930s reconstruction of Orchard Beach, and the bay became known as the "Orchard Beach Lagoon", or the Lagoon for short.[92][161] The lagoon between Orchard Beach and the Westchester border had been popular for regattas, or boat races, for decades, but it was neglected through the 1940s and 1950s. Rocks, weeds, and unwanted cars were tossed into the lagoon regularly.[162]

The lagoon was chosen as the site of the 1964 Summer Olympics rowing trials,[2] at which point it was widened and dredged, becoming a four-lane, 2,000-meter (6,600 ft) rowing track.[163][164][165] The track, which cost $630,000,[163] was hosted jointly by the city and the organizers of the 1964 New York World's Fair. New York City hosted several of the 1964 Olympic trials at various locations as part of the World's Fair the same year.[164] Afterward, the now-unnamed lagoon was used by New York-area colleges for boating regattas, since it had been determined to be one of the most suitable locations for boat racing in the United States. Multiple colleges, including Columbia, Manhattan, St. John's, Fordham, Iona, and Yale, utilized the lagoon for collegiate rowing practice.[162]

Turtle Cove

Turtle Cove is a small cove along the north side of City Island Road west of Orchard Beach Road.[136] Around the early 1900s, a land berm was created across Turtle Cove for rails for horsecars. This berm caused the north end of Turtle Cove to become mostly freshwater, which attracted freshwater drinking rare birds in the meadow. A 3-foot (0.91 m) diameter concrete culvert was placed across the berm to allow salt water from Eastchester Bay, but leaves and vegetation blocked this culvert.[134] Starting in June 2009, NYC Parks started a restoration project for the cove, removing the old culvert and digging a canal to flood the north end of the cove with salt water. NYC Parks then placed a foot bridge across the canal. Some 11 acres (4.5 ha) of forest were also restored, with 10,000 trees being replaced.[166] The cove also contains a batting cage and a golf center with miniature golf, PGA simulators, and grass tees.[167]

Notable natural features

Glover's Rock

Glover's Rock (40°51′54″N 73°48′19″W / 40.86507°N 73.805244°W), a giant granite glacial erratic, has a bronze plaque commemorating the Battle of Pell's Point.[20] However, contrary to popular belief, the rock had nothing to do with the battle.[168] In their respective books, Henry B. Dawson (1886) and William Abbatt (1901) both wrote that Colonel John Glover reputedly stood on the rock and watched the British forces land during the battle.[169][30]: 255 This claim is erroneous, as these distances were computed based on an inaccurate map using estimates recorded by Glover in his "Letter from Mile Square" on October 24, 1776.[168] The actual location where Glover watched British forces land is closer to the second tee of the current Split Rock Golf Course.[168] The rock is only known as such today because Abbatt includes a labeled photograph of it in his book.[30]: 4

Split Rock

Split Rock (40°53′11″N 73°48′54″W / 40.88648°N 73.81492°W), a large dome-shaped granite boulder measuring approximately 25 feet (7.6 m) from north to south and 15 feet (4.6 m) from east to west, is located at the intersection of the New England Thruway and Hutchinson River Parkway, on a triangular parcel of land formed by these roads and a ramp that leads from the northbound Parkway to the northbound Thruway.[170] The only public access to the rock is by a pedestrian trail that begins on Eastchester Place, outside the park. The Bridle Trail passes close to the rock, but is separated from the rock by the parkway's exit ramp.[136] Another park trail, called the Split Rock Trail, leads from the Bartow Circle to the rock.[171]

The Split Rock Golf Course was named after the rock.[2] Split Rock also gives its name to Split Rock Road in Pelham Manor,[172] which used to extend into the park itself.[173] The rock appears to be a glacial erratic and derives its name from a large crevice dividing the stone into two half domes. The huge rock broke in half about 10,000 years ago under the stress of glacial movements.[174][175]

Split Rock is also the location near where, in 1643, Anne Hutchinson and members of her family were massacred by Native Americans of the Siwanoy Tribe. Her daughter, Susanna, the only member of the family to survive the massacre, was at the rock during the time of the attack, which took place at the house, a distance away.[16]: 237 In 1904, the New York State Legislature approved the placement of a bronze tablet on Split Rock in honor of Anne Hutchinson.[176] The tablet was installed in 1911 by the Colonial Dames of New York.[177][178] However, it was stolen in 1914.[179][180] The plaque reads:[180][181]

ANNE HUTCHINSON

Banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1638[b]

Because of her Devotion to Religious Liberty This Courageous Woman

Sought Freedom from Persecution in New Netherland

Near this Rock in 1643 She and her Household

were Massacred by Indians

This Tablet is placed here by the Colonial Dames of the State of New York

ANNO DOMINI MCMXI Virtutes Majorum Filiae Conservant[181]

The boulder is of enough historic importance that in the 1950s, Theodore Kazimiroff of the Bronx Historical Society convinced officials to move the planned Interstate 95 (New England Thruway) a few feet north to save Split Rock from being dynamited.[182][183]

Treaty Oak

Treaty Oak (40°52′16″N 73°48′14″W / 40.871°N 73.804°W) is located on the Pell estate near the Bartow-Pell Mansion. It was said that under this oak tree, a treaty was signed between Thomas Pell and Siwanoy Chief Wampage, selling Pell all land east of the Bronx River in what was then Westchester.[13][184] The Society of the Daughters of the Revolution erected a protective fence and a plaque near the tree, but it was destroyed by lightning in 1906[185][13] and toppled in a storm in March 1909.[186] Parts of the original tree were donated to museums and historical societies.[187]

A replacement tree was planted in 1915,[188] and the current tree at the location is an elm.[189]

Wildlife sanctuaries

Thomas Pell Wildlife Sanctuary and the Hunter Island Marine Zoology and Geology Sanctuary consist of a total of 489 acres (1.98 km2) of marshes and forests within Pelham Bay Park. They were created in 1967 as a result to opposition to a planned landfill on the site of the current sanctuaries.[190] Much of the forests in these sanctuaries are estimated to be at least three centuries old, dating to colonial times.[191] The park also has two nature centers at Orchard Beach and in the southwestern section of the park.[134][192]

Thomas Pell Wildlife Sanctuary

The Thomas Pell Wildlife Sanctuary, named for Thomas Pell, makes up the westerly part of Pelham Bay Park.[193] Included within its bounds are Goose Creek Marsh and the saltwater wetlands adjoining the Hutchinson River[136] as well as Goose Island, Split Rock, and the oak–hickory forests in tidal marshes bordering the Split Rock Golf Course.[194] The area is home to a variety of wildlife including raccoon, egrets, hawks, and coyotes.[134]

Hunter Island Marine Zoology and Geology Sanctuary

Located north of Orchard Beach, the Hunter Island Marine Zoology and Geology Sanctuary encompasses all of Twin Islands, Cat Briar Island, Two Trees Island, and the northeastern shoreline of Hunter Island.[195][196] It contains many glacial erratics, large boulders that were deposited during the last ice age,[195][194] as well as the largest continuous oak forest in Pelham Bay Park. The sanctuary supports a unique intertidal marine ecosystem that is rare in New York State.[134][82][147]

Wildlife-related activities

The park is a popular spot for bird watching, with up to 264 species having been spotted. Common bird species observed within the park include great horned owl, northern saw-whet owl, barn owl, red-tailed hawk, and warblers on Hunter Island;[197] American woodcock, willow flycatcher, northern harrier, woodpeckers, black-capped chickadee, tufted titmouse, and white-breasted nuthatch in the meadow west of Orchard Beach;[198] and various songbirds and sparrows north of the Pelham Bay Golf Course.[199] Birds in the park's waters include loons, grebes, cormorants, anseriformes, and gulls from the Twin Island coasts;[200] greater yellowlegs, lesser yellowlegs, loons, hooded merganser, Canada goose, mallard, and egrets in Eastchester Bay and Turtle Cove;[199] and osprey and waterbirds in the lagoon.[201] This is a result of Pelham Bay Park's location within one of the major seasonal bird migration corridors. The National Audubon Society has designated the park as one of four "Important Bird Areas" within the city.[202][203]

Saltwater fishing is also popular within the park, but is prohibited on Orchard Beach when the beach is open during the summer.[203] There are two major areas where fishing is allowed: in the southern part of Pelham Bay Park near Eastchester Bay; and in the northern part near the Lagoon, Turtle Cove, and northern beach jetty.[204]

South of Orchard Beach is a 25-acre (10 ha) meadow that hosts the only known population of the moth species Amphipoea erepta ryensis.[134][205][206] Another population used to exist in Rye, Westchester County.[207][208]

Surroundings

Pelham Bay Park is bounded by the town of Pelham, New York, to the north; City Island and Long Island Sound to the east; Watt Avenue and Bruckner Expressway to the south; and the Hutchinson River Parkway to the west.[2][136]

North of the park is the village of Pelham Manor in Westchester County, and a 250-foot-wide (76 m) strip of land that is part of New York City due to a boundary error. Owners of the several dozen houses on the strip have a Pelham Manor zip code and phone numbers and their children attend Pelham public schools, but as Bronx residents pay much lower property taxes than their Westchester County neighbors.[209]

To the southeast, the City Island Bridge connects the park to City Island.[210][211]

Landmarks, attractions, and recreational features

Orchard Beach

Orchard Beach (40°52′02″N 73°47′45″W / 40.867304°N 73.795946°W), a public beach, is part of Pelham Bay Park[69] and comprises the borough's only beach.[93] The 1.1-mile-long (1.8 km), 115-acre (47 ha)[212] beach faces the Long Island Sound and is laid out in a crescent shape with a width of 200 feet (61 m) during high tide.[213] An icon of the Bronx, Orchard Beach is sometimes called the Bronx Riviera,[93][214][215][216] the Riviera of New York City,[217] Hood Beach,[216] or the Working Class Riviera.[218] It contains a set of twin pavilions, which were both landmarked by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2006.[219]

Bronx Victory Column & Memorial Grove

The Bronx Victory Column & Memorial Grove is a 70-foot-tall (21 m) limestone column that supports a bronze statue of Winged Victory on Crimi Road in the park. The grove of trees that surround the statue were originally planted on the Grand Concourse in 1921 by the American Legion;[220] they were removed in 1928 when construction began on the IND Concourse Line (B and D trains).[221] In 1930, the American Legion revealed plans to relocate the grove to Pelham Bay Park, where there would be a new monument to honor Bronx servicemen. The monument was designed by John J. Sheridan and sculpted by Belle Kinney and Leopold Scholz.[221][220] On September 24, 1933, the monument and grove was dedicated to the 947 Bronxites who died in World War I.[221][222] The column is supported by a 18-foot-tall (5.5 m) pedestal. The statue itself is 18 feet tall and 3,700 pounds (1,700 kg), located atop a series of 14 discs. This brings the monument's aggregate height to more than 120 feet (37 m).[222] While officially a memorial to servicemen from the Bronx,[221] it is also a favorite location for wedding photography.[223]

Bartow-Pell Mansion

A 19th-century plantation-style mansion called the Bartow–Pell Mansion (located at 40°52′18″N 73°48′21″W / 40.871611°N 73.805944°W) is a colonial remnant done in Greek revival style.[224][32] The mansion, originally built in 1842, was sold to the city in 1880, which maintained it until 1914, when the city and International Garden Club assumed joint maintenance of the building.[32][33] Since 1975, it has been a National Historic Landmark.[225][33]

Pelham Bay and Split Rock Golf Courses

The Pelham Bay Golf Course opened in 1901, followed by the Split Rock Golf Course in 1935.[84] The courses, consisting of eighteen holes each, share an Art Deco clubhouse (located at 40°52′30″N 73°48′35″W / 40.874967°N 73.80972°W).[226] The courses are separated by the Northeast Corridor railroad tracks, with the Split Rock course to the northwest and the Pelham Bay course to the southeast.[136]

Plans for a golf course in Pelham Bay Park have existed since soon after the park was founded. In 1899, the New York Athletic Club approached Lawrence Van Etten, an architect renowned for designing golf courses, for a request to construct an 18-hole course within the park.[84] The proposed course would be bounded by Pelham Manor to the north; the Harlem River and Port Chester Railroad (now Northeast Corridor) tracks to the west; and Shore Road to the southeast. The city was building Van Cortlandt Park's golf course at the time, but the Bronx district parks commissioner approved Van Etten's plan. Originally, the club wanted to construct a park on Hunter Island, but Van Etten felt that the island was too small for a full 18-hole course.[227] Once the Van Cortlandt Park course was opened, city officials started focusing on plans for the Pelham course.[228]

In April 1900, surveyors began studying part of the park as a possible location for a golf course.[229][228] Later that month, workers began construction at the northwest course location. It was expected that the course would open in June or July of that year,[229][230] but that the work would not be fully complete until September.[228] New York City greenskeeper Val Flood later stated that he thought the course would open by August; however, by September 1900, work on the course had hardly started due to a lack of workers.[231] By the end of 1900, NYC Parks reported that seeds had been planted for nine greens, and two bunkers and one hazard had been created.[65]: 23 The course opened in 1901,[66]: 69 but did not gain popularity until 1903 when overcrowding at the Van Cortlandt course drove players to use the less crowded Pelham Bay course instead.[232]

In 1934, a new 18-hole course was announced for the north side of the park, along with a renovation to the Pelham Bay course under the WPA.[74][233] It was part of the rebuilding of 10 golf courses in the city.[234] The new course brought the total number of holes in the park's courses to 36, with each course being between 3,000 and 3,300 feet (910 and 1,010 m) between the first and last tees. This comprised two 18-hole courses or four 9-hole courses. There was also a new two-story brick Greek Revival clubhouse adjacent to both of the 18-hole courses, with a golf store, Pro Shop, cafeteria, lockers, restrooms, and showers. Construction started on the new course and clubhouse in September 1934.[235] The new Split Rock course, based on a plan from John van Kleek, opened in 1935[84] along with the rebuilt Pelham Bay course.[83]

Bronx Equestrian Center

The northern section of Pelham Bay Park is the home of the Bronx Equestrian Center on Shore Road, where visitors can ride horses and ponies through the parks' trails or obtain riding lessons.[236][132] The Bronx Equestrian Center also provides wagon rides and hosts wedding events.[132]

Southwestern section

The southwestern part of Pelham Bay Park contains several recreational facilities, but unlike the rest of the park, the southwestern section mainly serves the nearby neighborhoods.[4][237] The southwest park's largest point of interest is the Aileen B. Ryan Recreational Complex, which contains a running track, two baseball fields, and the Playground for All Children, a play area with special features for physically handicapped children.[238] Another playground, the Sweetgum Playground, is located near Bruckner Boulevard. The 0.25-mile (0.40 km) Pelham Track and Field includes an artificial turf football field as well as long jumping.[220] The southwest park also contains a dog run, four more baseball fields (for a total of six), two bocce courts, several basketball courts, and nine tennis courts.[239] This section of the park also includes the Pelham Bay Nature Center.[220] The neighborhood of Pelham Bay is across the Bruckner Expressway from this section of the park.[4]

A long and narrow 41-acre (17 ha) woodland called Huntington Woods, located on the southern border of this park, is named after the tract's last owners. Archer Milton Huntington, the founder of the Hispanic Society of America, and his wife, sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington, had acquired the property in 1896 after the park had been established. The city added 31.6 acres (12.8 ha) of Huntington's estate to the park in 1925 and annexed the remaining land in 1933.[240]

The southwestern park also contains two monuments. American Boy was commissioned in 1923 by French sculptor Louis St. Lannes and carved from one block of Indiana Limestone.[238] A tribute to the athletic body, it once stood outside the Rice Stadium and Recreation Building; the stadium, named and funded by the widow of Isaac Leopold Rice, stood at the site from the 1920s until 1989. The former stadium site is now the Pelham Track and Field.[238][241] The other is the Bronx Victory Column & Memorial Grove.[220][222][221]

Management

A nonprofit organization called Friends of Pelham Bay Park (founded in 1992) manages the park, while NYC Parks owns and operates the land and facilities.[242] Compared to the Central Park Conservancy, Friends of Pelham Bay Park does not receive as much funding.[243] Before 1992, there was no private maintenance of the park;[244] the earliest efforts for such a thing date to 1983, when an administrator was appointed to oversee both Van Cortlandt and Pelham Bay Parks.[245]

Transportation

Bridges

As part of the city's acquisition of Pelham Bay Park in 1888, NYC Parks claimed responsibility for maintenance over the western end of the City Island Bridge, which was within the park.[246]: 433 (PDF p.502) [52]: 695 The City Island Bridge had been built by the 1870s.[247] By 1892, the bridge was in need of maintenance,[61]: PDF p.114 and a proposal for a replacement bridge was approved in 1895.[63]: 41 (PDF p.115) The replacement bridge started construction in late 1898 and was completed in 1901.[248]

The Pelham Bridge, which had opened in 1871 on the site of two previous bridges,[249] was also incorporated into the park.[63]: PDF p.443 [52]: 695 Planning for a new bridge started in 1901,[66]: 64 and NYC Parks transferred the responsibility for constructing the new bridge to the Department of Bridges in 1902.[67]: 117 (PDF p.86) A new stone bridge was opened in 1908 to accommodate higher volumes of traffic.[250][251]

The century-old City Island Bridge was subsequently replaced again in the 2010s. Planning for the new bridge started in 2005,[252] though a lack of funding delayed the start of construction to 2012.[253] The new bridge was completed in 2015, and the old one was demolished soon after.[254]

Roads

The park is traversed by the Hutchinson River Parkway on its west side.[3] The New England Thruway (I-95), a partial toll road, also has a short highway section in the park's northwest corner.[210][136] A partial interchange between the two roads is located within the park.[210] To the south, an exit from the Hutchinson River Parkway provides direct access to the park, Orchard Beach, and City Island. The exit and entrance ramps lead east to the Bartow Circle, where the ramps intersect with Shore Road, which runs roughly southwest-northeast, and with Orchard Beach Road, which leads southeast to the Orchard Beach parking lot.[210] Slightly to the southwest of Bartow Circle is the T intersection of Shore Road and City Island Road, which marks the northwest terminus of the latter road. Shore Road continues across the Pelham Bridge to the southwest corner of the park, then turns west and continues onto Pelham Parkway.[210] Meanwhile, City Island Road continues southeast to City Island Circle, where it intersects with Park Drive, a road that connects to Orchard Beach Road in the north and Rodman's Neck in the south. City Island Road then continues southeast across the City Island Bridge to the eponymous island.[210]

NYC Parks assumed responsibility for the park's roads in 1888 and gradually paved and expanded them over the following decades.[52]: 695 An expansion of Eastern Boulevard (later Shore Road) began in 1895.[63]: PDF p.175 In 1897, the city started extending Pelham Parkway through to Eastern Boulevard.[255]: 258 (PDF p.328) By 1902, Eastern Boulevard was referred to as "the Shore drive" since it ran close to the LeRoy's Bay shore. The same year, NYC Parks built a 4,230-foot (1,290 m) dirt path, which connected Glover's Rock to Shore Road. Another 4,870-foot-long (1,480 m) dirt road to Pelham Bridge was also built, and a 6,485-foot (1,977 m) pedestrian path from City Island Bridge to Bartow Station was built.[67]: 116–117 (PDF pp.85–86)

The Hutchinson River Parkway in Pelham Bay Park replaced the old Split Rock Road in the park. The original roadway was an undivided, limited-access parkway, designed with gently sloping curves, stone arch bridges, and wooden lightposts. The original 11-mile (18 km) section included bridle paths along the right-of-way. There was also a riding academy where the public could rent horses.[256] The parkway is named for Anne Hutchinson and her family, and passes through the part of the park near where the Hutchinsons were killed by the Siwanoy.[256] The modern-day parkway was extended south from Westchester through Pelham Bay Park in December 1937.[257][173]

The second highway through the park, the New England Thruway, opened in its entirety in October 1958, connecting the Bruckner Expressway in the south with the Connecticut Turnpike in the northeast.[258]

Public transport

Pelham Bay Park is served by the New York City Subway at its eponymous station on the west side of the Bruckner Expressway,[259] which is served by the 6 and <6> trains.[260] The station is part of the former Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT)'s Pelham Line. The line's northern terminus is located at the southeast corner of Pelham Bay Park, and the IRT station there opened in December 1920.[261][262] An exit from the station leads onto a pedestrian bridge that crosses the expressway and leads directly to the park.[237][259]

MTA Regional Bus Operations' Bx29 route and Bee-Line Bus System's 45 route also stop at the park.[263] The southbound Bx29 makes three stops in the park: on Bruckner Boulevard near the subway station; at the intersection of Shore Road and City Island Road; and at City Island Circle.[264] Meanwhile, Bee-Line's 45 route stops near Bartow-Pell Mansion.[237] The Bx12 bus serves Orchard Beach during the summer only.[265]

Railroads

The Harlem River and Port Chester Railroad was chartered in 1866,[266] connecting the Harlem River in the south and Port Chester in the north. The railroad opened in 1873, with some portions passing through the current park.[267] The route, a branch of the New Haven Line operated by the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad, contained six stations. One of these stations, called alternatively City Island or Bartow, in Pelham (now part of the park).[268] In 1895, the railroad re-acquired some of the land from the park[154]: 205 (PDF p.297) In 1906, ownership of the Shore Road overpass over the Harlem and Port Chester railroad line was transferred to the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad.[269]

A railroad of some sort also connected City Island and Pelham Bay Park from 1887 to 1919. Originally composed of the separate Pelham Park Railroad Company and the City Island Railroad, the 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) narrow-gauge horsecar route was operated by the former of the two companies, which ran service between the Bartow station of the Harlem River and Port Chester Railroad and Brown's Hotel on City Island. The 3.2-mile (5.1 km) route was complete by 1892.[270] The IRT absorbed the two companies in 1902 and started designing its own monorail in 1908.[270][271] The monorail's first journey in July 1910 ended with the monorail toppling on its side,[272][273][271] and although service resumed in November 1910, the monorail went into receivership in December 1911.[274] The monorail ceased operation on April 3, 1914,[275][276][277] and was subsequently sold to the Third Avenue Railway,[278] which abandoned the line on August 9, 1919.[279]

The Harlem River and Port Chester tracks were maintained by the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad.[280]: 1092 New stations designed by Cass Gilbert were opened in 1908, but the line's stations were all closed by 1937, having suffered from low ridership.[277] During the late 20th century, the old Harlem River and Port Chester tracks went through a series of ownership changes, and in 1976, Amtrak bought the tracks and integrated the route into its Northeast Corridor.[280]: 81 The station house for the line's Bartow station still exists, albeit as a deteriorated shell;[281] the station's roof burned down after it was closed.[277] An overgrown path leads from the bridle trail to the former station site.[282]

The city renovated the Shore Road railroad overpass in the early 2000s. Citing the 1906 deed that transferred the bridge's maintenance to the company that owned the railroad below it, the city then filed a lawsuit to make Amtrak pay for the renovation. The United States District Court for the District of Columbia ruled in favor of Amtrak in 2013.[269][283]

Paths

Bicycle paths go to all parts of the park and west to Bronx Park, east to City Island, and north to Mount Vernon.[284] The bike trails within the park itself are of varying difficulties.[132]

Scenic trails

The Kazimiroff Nature Trail, a wildlife observation trail, opened in 1986.[116][115] It traverses 189 acres (76 ha) of Hunter Island. Much of the island's natural features are found along the trail.[285] It was opened in 1986[116] and comprises two overlapping lasso-shaped paths, one slightly longer than the other.[115][285]

The Siwanoy Trail consists of a trail system that originates in the Central Woodlands section of the park. Originating at City Island Road, it bears to the northeast before splitting into two spurs, one going east to the Rodman's Neck meadow and the other going north around Bartow Circle. At the circle's eastern side, the trail splits again. One spur goes northeast in a self-closing loop to the Bartow-Pell Mansion, and the other goes northwest to connect to Split Rock Trail before going around the Hutchinson River Parkway's interchange with Orchard Beach Road.[136]

Split Rock Trail originates at Bartow Circle and stretches for 1.5 miles (2.4 km) along the west side of the park.[136][171][195] First designated in 1938 along the path of the former Split Rock Road,[173] the path was renovated in summer 1987.[171]

The park is also traversed by a bridle path.[2] That path circumscribes both golf courses, with a spur to the Bronx Equestrian Center.[136]

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ a b c The exact size is disputed, with some sources giving 2,764 acres (1,119 ha),[1][2] 2,765 acres (1,119 ha),[3] or 2,772 acres (1,122 ha).[4] Recalculations of city park sizes in 2013 determined that Pelham Bay Park was 2,772 acres.[5]

- ^ The New York Times quotes this line as "Massachusetts Colonies" rather than "Massachusetts Bay Colony".[180]

References

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 2006, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jackson 2010, p. 986.

- ^ a b c d e f g Smith, Sarah Harrison (2013). "Exploring Sand and Architecture at Pelham Bay Park". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c Gregor, Alison (April 27, 2014). "Pelham Bay, the Bronx: A Blend of Urban and Suburban". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ a b c Foderaro, Lisa W. (May 31, 2013). "How Big Is That Park? City Now Has the Answer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 1, 2013. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- ^ O'Hea Anderson 1996, p. 4.

- ^ New York City Parks Department 1987, p. 2.

- ^ a b O'Hea Anderson 1996, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d "Pelham Bay Park Highlights : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. September 29, 2006. Archived from the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ "Siwanoy Trail". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. March 20, 1989. Archived from the original on October 1, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- ^ a b Leslie Day (May 10, 2013). "Chapter 2: The Bronx". Field Guide to the Natural World of New York City. JHU Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-1149-1.

- ^ a b c Stevens, J.A.; DeCosta, B.F.; Johnston, H.P.; Lamb, M.J.; Pond, N.G.; Abbatt, W. (1892). The Magazine of American History with Notes and Queries. A. S. Barnes. p. 408. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Twomey 2007, p. 212.

- ^ "Owen F. Dolen Park Monuments". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. April 30, 1926. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ a b Champlin, John Denison (1913). "The Tragedy of Anne Hutchinson". Journal of American History. 5 (3): 11.

- ^ a b c d LaPlante, Eve (2004). American Jezebel, the Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman who Defied the Puritans. San Francisco: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-056233-1. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- ^ Barr 1946, p. 5.

- ^ Anderson, Robert Charles (2003). The Great Migration, Immigrants to New England 1634–1635. Vol. III G-H. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. pp. 479–481. ISBN 0-88082-158-2.

- ^ Darlene R. Stille (August 2006). Anne Hutchinson: Puritan Protester. Capstone. pp. 85–88. ISBN 978-0-7565-1784-7.

- ^ a b c "War Record of Pelham Bay Park; War Record of Pelham Bay Park" (PDF). The New York Times. August 14, 1921. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c Pell 1917, p. 5.

- ^ a b Jenkins 2007, p. 35.

- ^ O'Hea Anderson 1996, p. 12.

- ^ Pell 1917, p. 12.

- ^ Pell 1917, p. 16.

- ^ ASHPS Annual Report 1909, p. 63.

- ^ Jenkins 2007, p. 313.

- ^ McCullough, David (2006). 1776. New York: Simon and Schuster Paperback. p. 209. ISBN 0-7432-2672-0.

- ^ a b Ward, Christopher (1952). The War of the Revolution, Volume 1. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- ^ a b c d Abbatt, William (1901). The Battle of Pell's Point. New York: University of California.

- ^ Jackson 2010, p. 161.

- ^ a b c d e Gray, Christopher (April 28, 2002). "STREETSCAPES / THE BARTOW-PELL MANSION IN THE BRONX; 1842 Home, Now a Museum, in City's Largest Park". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c Castellucci, John (March 18, 1977). "Garden club's mansion official landmark now" (PDF). The Daily News. Tarrytown, New York. p. A5. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ Olmsted, Frederick Law; Vaux, Calvert; Croes, John James Robertson (1968). Fein, Albert (ed.). Landscape into cityscape: Frederick Law Olmsted's plans for a greater New York City. Cornell University Press. p. 331. ISBN 9780442225391.

- ^ Gonzalez 2004, p. 47.

- ^ Golan, Michael (1975). "Bronx Parks: A Wonder From the Past". Bronx County Historical Society Journal. 12 (2). The Bronx County Historical Society: 32–41.

- ^ Gonzalez 2004, p. 49.

- ^ "THE NEED OF MORE PARKS; FIRST MEETING OF THE NEW-YORK PARK ASSOCIATION YESTERDAY" (PDF). The New York Times. November 27, 1881. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ New York City Parks Department & Storch Associates 1986a, p. 3.

- ^ a b "The Albany Legislators" (PDF). The New York Times. Albany, New York. March 25, 1884. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ a b New York City Parks Department & Storch Associates 1986a, p. 56.

- ^ Mullaly, John (1887). The New Parks Beyond the Harlem: With Thirty Illustrations and Map. Descriptions of Scenery. Nearly 4,000 Acres of Free Playground for the People. New York: Nabu Press. pp. 117–138. ISBN 978-1-141-64293-9.

- ^ "Bronx Park: History". New York City Parks Department. Archived from the original on January 13, 2022. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ "Proposed New Parks" (PDF). The New York Times. January 24, 1884. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ a b New York City Parks Department & Storch Associates 1986a, pp. 57–58.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landmarks Preservation Commission 2006, p. 3.

- ^ a b "Pelham as Sick of the Park as We Are". New York Sun. March 25, 1887. p. 4. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2017 – via Library of Congress.

- ^ "PELHAM IN DESPAIR.; FORESEEING BANKRUPTCY THROUGH THE PARK SCHEME" (PDF). The New York Times. February 5, 1888. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ "THE PELHAM PARK.; WESTCHESTER PEOPLE ASK MAYOR HEWITT'S AID TO KILL THE SCHEME" (PDF). The New York Times. March 25, 1887. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ "Rough on Pelham, but Must We Pay for It?". The Sun. February 5, 1888. p. 11. ISSN 1940-7831. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017 – via Library of Congress.

- ^ "TO TAX PELHAM BAY PARK — TRYING TO BLEED NEW-YORK HEAVILY — AN ALMOST USELESS PARK THAT MAY COME NIGH — TWO SIDES TO THE STORY". New York Tribune. February 5, 1888. ISSN 1941-0646. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017 – via Library of Congress.

- ^ a b c d e Laws of the State of New York: Passed at the Session of the Legislature. Laws of New York. New York State Legislature. 1888. pp. 693–696. hdl:2027/nyp.33433090742036. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2017 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ Jackson 2010, p. 987.

- ^ a b c d Pelham Bay Park: History (Report). New York City: City of New York. 1986. pp. 2, 11–12.

- ^ ASHPS Annual Report 1909, pp. 64–66.

- ^ "The Courts". New York Tribune. March 16, 1889. p. 4. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2017 – via Library of Congress.

- ^ "PELHAM BAY PARK" (PDF). The New York Times. August 30, 1889. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 3, 2017.

- ^ Bolotin, Norm; Laing, Christine (1992). The World's Coumbian Exposition: The Chicago World's Fair of 1893. University of Illinois Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780252070815.

- ^ "Board of Commissioners of the NYC Dept of Public Parks – Minutes and Documents: Minutes and Documents: May 8, 1889 – April 30, 1890" (PDF). New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. April 30, 1890. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ "Board of Commissioners of the NYC Dept of Public Parks – Minutes and Documents: May 13, 1891 – April 28, 1892" (PDF). New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. April 30, 1892. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ a b "Board of Commissioners of the NYC Dept of Public Parks – Minutes and Documents: May 4, 1892 – April 26, 1893" (PDF). New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. April 30, 1893. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ "Board of Commissioners of the NYC Dept of Public Parks – Minutes and Documents: May 1, 1893 – April 25, 1894" (PDF). New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. April 30, 1894. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Board of Commissioners of the NYC Dept of Public Parks – Minutes and Documents: May 2, 1894 – April 25, 1895" (PDF). New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. April 30, 1895. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ a b "1899 New York City Department of Public Parks Annual Report" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. December 31, 1899. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b "1900 New York City Department of Public Parks Annual Report" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. 1900. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ a b c "1901 New York City Department of Public Parks Annual Report" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. 1901. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ a b c "1902 New York City Department of Public Parks Annual Report (Part 2)" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. 1902. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 16, 2017. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ "1903 New York City Department of Public Parks Annual Report" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. 1903. pp. 88–89. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 16, 2017. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Orchard Beach". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on November 20, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b "1906 New York City Department of Public Parks Annual Report" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. 1906. pp. 87–88. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ a b Caro 1974, p. 366.

- ^ "PUBLIC ATHLETIC FIELD" (PDF). New York Evening Post. July 16, 1904. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ a b c Seitz & Miller 2011, p. 132.

- ^ a b c d "THE NEW DEAL FOR THE PARKS OUTLINED BY THEIR DIRECTOR; Commissioner Moses Would Develop the City's Recreation Areas And Then Coordinate Them With the State Park System By DOROTHY DUNBAR BROMLEY". The New York Times. February 11, 1934. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Forero, Juan (July 9, 2000). "Slice of the Riviera, With a Familiar Bronx Twist". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- ^ Caro 1974, p. 364.

- ^ "NEW 'JONES BEACH' PLANNED IN BRONX; Moses Wants Model Resort at Pelham Bay Park -- Orders CWA Work Razed". The New York Times. February 28, 1934. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 2006, p. 2.

- ^ "WORK RELIEF BOOMS PARKS; Moses Pushes Program to Expand Greatly the Present Facilities for Recreation" (PDF). The New York Times. September 22, 1935. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "MOSES IS UPHELD IN PARK CAMP BAN; Court Refuses to Interfere in Razing of 625 Bungalows at Orchard Beach" (PDF). The New York Times. May 16, 1934. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "Moses Wins Again in Row Over Camps; Clearing of Orchard Beach Sites Is Begun" (PDF). The New York Times. June 12, 1934. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Hunter Island". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ a b Britton, A.D. (June 2, 1935). "TAKING MENTAL HAZARD OUT OF CITY GOLF; The Player on the Public Links Has a New Dispensation, for Old Courses Have Been Improved and Others Built" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Cornish, G.S.; Whitten, R.E. (1993). The architects of golf: a survey of golf course design from its beginnings to the present, with an encyclopedic listing of golf course architects and their courses. HarperCollins. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-06-270082-7. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 2006, p. 7.

- ^ Caro 1974, p. 367.

- ^ "TO EXHIBIT MODEL OF ORCHARD BEACH; Park Department Will Display Miniature Tomorrow at Bronx Court House". The New York Times. July 7, 1935. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 2006, p. 8.

- ^ "PARKS' OWN POLAR CIRCLE". The Daily Plant. New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. February 7, 2001. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b "REFUSE DUMPING OPPOSED; Bronx Civic Leaders Criticize Pelham Bay Park Project" (PDF). The New York Times. May 28, 1935. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ a b "TWO NEW BEACHES TO OPEN SATURDAY; Orchard, in Pelham Bay Park, Although Not Completed, Will Be Ready for Bathers" (PDF). The New York Times. June 13, 1937. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- ^ a b "Pelham Bay Dam Approved" (PDF). The New York Times. April 14, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ a b c Jackson 2010, p. 958.

- ^ "PUBLIC IS GREETED AT ORCHARD BEACH; Uncompleted Aquatic Center Dedicated -- Mayor, Moses Exchange Thrusts. FORMER DECRIES CENSURE Also Hails WPA as an 'American' Relief System -- Park Head Defends Criticism. PUBLIC IS GREETED AT ORCHARD BEACH" (PDF). The New York Times. July 26, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ "TWO CITY BEACHES OPEN FOR SEASON; Jacob Riis Park, on the Ocean, Attracts 2,500--Few Bathers Brave the Chilly Water 3,000 AT ORCHARD BEACH At Least 1,000 Try Swimming in Long Island Sound--Joint Capacity of 500,000 NEW YORK OPENS TWO NEW RECREATIONAL AREAS TO PUBLIC". The New York Times. June 26, 1937. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 2006, p. 9.

- ^ Historical and Modern Orchard Beach, with a Brief Resume of the Surrounding Territory (Report). 1960. pp. 17–19.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 2006, p. 10.

- ^ "ORCHARD BEACH OPENS SHORE LINE EXTENSION" (PDF). The New York Times. May 31, 1947. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ 30 Years of Progress: 1934–1965, p. 69.

- ^ 30 Years of Progress: 1934–1965, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d e f Twomey 2007, p. 103.

- ^ a b c d Jackson 2010, p. 1118.

- ^ a b c d New York City Parks Department 1987, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Lorch, Donatella (November 14, 1989). "Residents Force Start of Cleanup At Bronx Dump". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- ^ a b c "State Denies Permit For Landfill Project" (PDF). Riverdale Press. May 23, 1968. p. 12. Retrieved October 6, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ "Tallapoosa Landfill Is Partial Defeat" (PDF). Riverdale Press. August 3, 1967. p. 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ "Nature-Lovers Lose Park Area To Landfill Forces in the Bronx" (PDF). The New York Times. July 28, 1967. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ "STATE MAY OPPOSE BRONX PARK DUMP; Official Says He May Deny Permit for Pelham Landfill" (PDF). The New York Times. August 29, 1967. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ a b "Council Passes Bill to Protect Wildlife Park" (PDF). Riverdale Press. November 21, 1968. p. 8. Retrieved October 6, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ "The Mountains of Waste" (PDF). The New York Times. May 16, 1975. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Poust, Mary Ann (May 19, 1983). "Report: Pelham Bay landfill contaminated with 'waste oils'" (PDF). Yonkers Herald Statesman. p. 3. Retrieved September 16, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ Blumenthal, Ralph (May 19, 1983). "Toxic Dumping in City Landfills Cited in a Study". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 14, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ a b "Drive begins for Kazimiroff memorial that will preserve Pelham Bay Park" (PDF). Riverdale Press. November 11, 1983. p. 8. Retrieved October 6, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ a b c d Bryant, Nelson (June 19, 1986). "OUTDOORS; KAZIMIROFF TRAIL TO OPEN IN BRONX". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Outdoors" (PDF). Riverdale Press. June 19, 1986. p. 23. Retrieved October 6, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ Heller Anderson, Susan; Dunlap, David W. (July 10, 1986). "NEW YORK DAY BY DAY; At Orchard Beach, Updated Fare". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Fernandez, Manny (April 13, 2011). "In New York Area, No Shortage of Grisly Dumping Grounds". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Fisher, Ian (November 28, 1992). "In Isolated Bronx Park, Death Visits Frequently". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Teltsch, Kathleen (November 17, 1990). "Urban Gift: Wilderness Regained". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 6, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- ^ Walker, Andrea K. (March 30, 1997). "Orchard Beach May Be Getting Its Day in the Sun". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Siegal, Nina (April 11, 1999). "NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: ORCHARD BEACH -- UPDATE; Water Park Plan Isn't Gliding Forward Now". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Ingrassia, Michelle (June 30, 2002). "GOING FOR THE GOLD: CITY VISIONARIES HOPE THEIR OLYMPIAN DESIGNS BRING THE 2012 SUMMER GAMES TO NEW YORK". NY Daily News. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "London beats Paris to 2012 Games". BBC Sport. July 6, 2005. Archived from the original on February 13, 2007. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "NYC Parks And U.S. Army Corps Of Engineers Launch $13 Million Orchard Beach Shoreline Protection Project". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. October 29, 2010. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ "FACT SHEET-Orchard Beach > New York District > Fact Sheet Article View". New York District. United States Army Corps of Engineers. June 26, 2012. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Calder, Rich (July 20, 2015). "Waterfront construction unearths more than 100 ancient artifacts". New York Post. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- ^ Sandy, William; Saunders, Cece (October 2012). "Phase IB Archaeological Survey Reconstruction of the Pelham Bay Park South Waterfront, NYC Parks contract X039 – 507M" (PDF). nyc.gov. Historical Perspectives. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved October 3, 2017.

- ^ Goodstein, Steven (July 31, 2015). "Native American artifacts discovered in Pelham Bay Park". Bronx Times. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved October 9, 2017.