They survived a ‘pogrom.’ Now Palestinians in Hawara fear life will only get worse

‘Next year, Hawara will be a real disaster,’ said Ziyad Abdullah, the owner of a struggling auto parts store in the West Bank town

An Israeli soldier stands guard in the Israeli-occupied West Bank city of Hawara in December. The town became notorious for settler violence after a February riot. Photo by Getty Images

HAWARA, West Bank — The only pool in this Palestinian town is ready for swimmers, but no one is slipping down either of its two water slides or enjoying any of the other attractions at “Howwara Country,” a sprawling complex also featuring steam baths, an event hall and two Ferris wheels. The resort sits just below a ring of Israeli settlements whose residents are considered among the most violent in the region by their Palestinian neighbors.

“Step-by-step, the people become afraid,” said Abu Assad, who built the complex nearly 15 years ago and wonders, with so few customers, if he can afford to keep it open.

In February, Hawara became shorthand for settler violence after hundreds of Israelis poured into the town from the surrounding hills and burned down four homes, torched hundreds of vehicles and destroyed dozens of olive trees. One Palestinian was killed by gunfire during the riot. Both Palestinians and Jews understood the violence as revenge for the killing of two Israeli brothers who were shot as they drove through Hawara the day before.

Several senior Israeli officials described the rampage as a pogrom, invoking the attacks on Jewish villages in Eastern Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries. And after Israel’s far-right finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, called for Hawara to be “wiped out” days after the riot, a host of leading American Jewish organizations announced they would boycott his March visit to the United States.

The scale of the February violence also stunned many of the 15,000 Palestinians who live in Hawara and the surrounding villages, despite the fact they had grown accustomed to stone throwing and similar provocations from the Israelis who live nearby.

Listen to That Jewish News Show, a smart and thoughtful look at the week in Jewish news from the journalists at the Forward, now available on Apple and Spotify:

Tensions have subsided some in the two months since the riot. A handful of buildings are still blackened from the arson and some thick store windows show marks from the stones and hatchets that settlers smashed them with. But other damage has been cleaned up and businesses have reopened.

Inhabitants say they hope to return to more peaceful times, although many anticipate a bleaker future — and not only because they expect more violence. They also expect a road, now under construction by the Israeli government, that will bypass their town. Those afraid of visiting today will have even more incentive to drive around its dozens of family-run shops and restaurants, and “Howwara Country” too.

“Next year, Hawara will be a real disaster,” said Ziyad Abdullah, the owner of a struggling auto parts store there.

The road ahead

Running a business in Hawara has not been easy for a long time. Assad, who opened his resort in 2009, said from almost the beginning vandals targeted it with tire slashings and racist graffiti. In recent years, drones began dumping bags of sewage into the swimming pool and settlement security guards arrived to detain guests for hours at a time. During the February riot, Assad said settlers lit vehicles on fire outside the hotel and cracked its water tanks with stones before descending on the houses and businesses below.

Almost as bad as the physical destruction from the riot was the damage to Hawara’s reputation, residents said. The town was first settled by Muslims centuries ago and an 1882 British survey of the region described it as “a straggling village of stone and mud” with “an appearance of antiquity.” The ruins of some stone buildings are still perched on the hillside above town, but these days Hawara is a major commercial district on the West Bank’s Route 60, which funnels both Israelis and Palestinians from the area around Jenin in the north to Hebron in the south.

The road, four lanes wide, cuts through the center of town, and is lined for 2 miles with restaurants hawking takeout, butchers with animal carcasses hanging from hooks and candy shops that draw on the reputation of nearby Nablus, which is known as “Palestine’s capital of sweet treats.” Houses, many of unfinished concrete, spread up the mountainside and down across the valley floor and the West Bank’s ubiquitous olive trees grow in the rocky soil behind many of the homes.

At Abdullah’s auto parts store, customers can purchase a truck battery for $30 that would cost $100 in Jerusalem. But Abdullah, who opened the shop 30 years ago, said his business tanked after the February riot.

Palestinians are afraid of stopping in Hawara and falling victim to violence from settlers. But they also cut down on travel along Route 60 after the Israeli army began more aggressively enforcing the local checkpoint, stopping some visitors from returning to other parts of the West Bank and forcing them to pile into crowded hotels in Nablus.

And then there’s the new bypass road being built by Israelis on land confiscated from Hawara and three other Palestinian villages in the area. Abdullah worries that the bypass road may spell the end for businesses like his, which rely on customers rolling past the commercial strip.

In the meantime, the 60-year-old busies himself with drawings. Pencil portraits, including one of Shireen Abu Akleh, the Palestinian journalist killed by an Israeli soldier last year, cover the walls of his garage, and among the piles of invoices and phones and cigarette packs piled on his desk is a sketchbook filled with more art.

The bypass road was announced three years ago at an estimated cost of $70 million. It’s meant to end the town’s notorious traffic jams, which have periodically exposed both Israelis and Palestinians to violence, as it is one of the few stretches where both groups are in close proximity in the northern West Bank. For years, many have considered the journey through the town dangerous, although Israelis and Palestinians disagree over the cause of some past incidents. In May of 2017, for example, two Israeli settlers driving by protests in Hawara opened fire on Palestinians, including shooting one in the back. Palestinians said the settlers tried to plow through protesters, while the settlers claimed they were thwarting an attempted lynching.

“I saw death in their eyes,” one of the settlers told The Times of Israel.

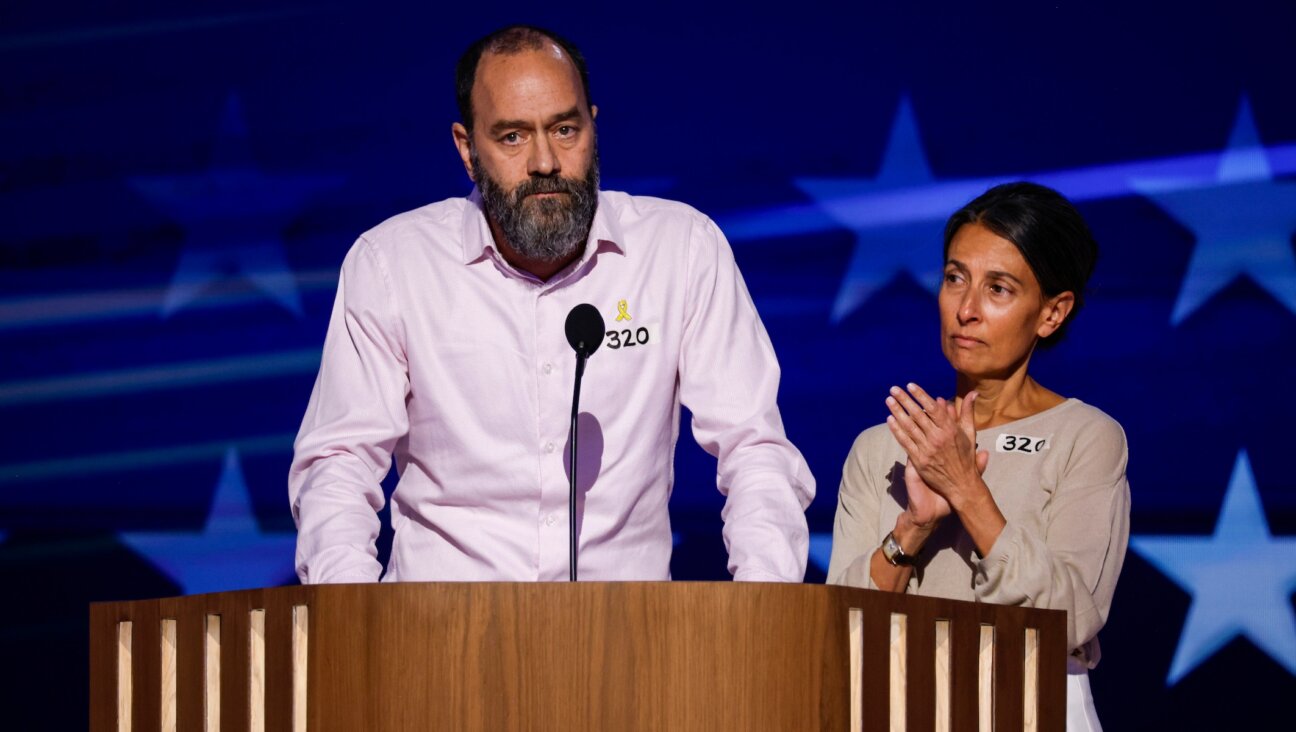

There was less disagreement over what preceded the riots this year. During a traffic slowdown on Feb. 26, an unidentified Palestinian shot and killed Hallel Yaniv, 21, and his brother Yagel, 19. The assailant waited by the side of the road before charging into traffic and shooting the brothers, who lived in the settlement of Har Brakha, just north of Hawara.

Abdullah, who speaks Hebrew from his days working as a bartender in Tel Aviv, said he knew the brothers as occasional customers and had been on friendly terms with them. “But this is a war,” he said.

(B'Tselem, an Israeli human rights organization, arranged this reporter's trip to Hawara, and translated most interviews from Arabic to English.)

Since February, the citizens of Hawara have suffered more abuse.

Abdullah’s adult son Hamed pulled out an old laptop with a video from March which shows settlers jogging by his shop, wearing masks, the fringes of their tallit hanging out. One at the back of the pack stops to light an old car on fire.

Also in March, two Israeli soldiers were wounded during a drive-by shooting in Hawara.

The riot and the protests

February’s riot struck a nerve among both Israeli and American Jewish leaders, inspiring levels of outrage seldom reached in response to settler violence in the past.

The events in Hawara took place at a watershed moment in Israel, during the first weeks of massive anti-government protests in which hundreds of thousands of Israelis, almost entirely Jews, took to the streets over a proposal to strip power from the Israeli Supreme Court. The country seemed to be falling apart, not along the seam that separates Jews from Palestinians, but over a continuing drama that pits right-wing and conservative Jewish voters against those who accuse them of trying to subvert democracy.

American Jewish leaders in March took the unusual step of traveling to Israel in order to share concerns about the legislation. Many American rabbis, from their pulpits and in stateside demonstrations, warned that the Knesset was poised to trample on the rights of everyone from LGBTQ Jews to diaspora Jews to Palestinians.

The images from Hawara also shocked Jews who saw other Jews terrorizing an entire town, which seemed disturbingly like the pogroms many of their ancestors had fled.

“How could it come to this, that Jewish young men should ransack and burn homes and cars?” said Moshe Hauser, the rabbinic leader of the New York-based Orthodox Union, in a statement.

The Israeli army responded to the riot by closing Hawara’s businesses for five days and soldiers are now posted along the main road with guns trained on motorists.

Days after the riot in Hawara, anti-government protesters in Tel Aviv, who have often avoided focusing on the Palestinians, shouted “Where were you in Hawara?” at Israeli police, suggesting their crowd control methods, which included water canons, would have been better applied to the rampaging settlers.

Inshrah Khmous, who lives at the edge of the road into Hawara, said she appreciated the sentiment but that the protesters’ question missed the point: Law enforcement was present in Hawara that night. Khmous hid inside her house for five hours during the February riot with seven of her female relatives. Settlers, she said, jumped over the fence into her courtyard, set cars on fire and hurled rocks through her windows. Soldiers stood on the street but came to the family’s aide only when the flames threatened to enter the house.

A photo of Israeli soldiers rescuing Khmous from the fire subsequently circulated on social media as an example of the army’s humanity. “They observed everything,” she said of the soldiers.

The Israeli military acknowledged in a statement to the Forward that the riot in Hawara "was extremely severe and should have been prevented."

"The violent riots instigated by Israeli civilians against the Israeli security forces and the Palestinians are being investigated by the Israel Police to the fullest extent of the law," a military spokesperson said.

You will not see this on the mainstream media ‼️

Israeli soldiers rescued a Palestinian woman from extremists who attacked Huwara town as a reaction to the terror attack earlier today.

I condemn terrorists, but I also condemn violence. It will not bring peace. pic.twitter.com/vcYMSr1d0u

— Hananya Naftali (@HananyaNaftali) February 26, 2023

Khmous, 76, was born in Jaffa, just south of Tel Aviv. Her family relocated to the West Bank following the 1948 war that led to the creation of Israel, and Khmous moved to Hawara, her husband’s hometown, in 1963.

“It’s a very sweet town,” she said. During Ramadan, her family used to sit in the courtyard until 2 a.m. But February’s violence left her fearful, so this year during the holiday, which fell in March and April, she hurried her nieces and other family members inside in the early afternoon.

Khmous is adamant she will stay in Hawara. The broken window panes have already been replaced and she has plans to clear the shattered glass and charred furniture from her courtyard. She wants to build a taller fence and a stronger gate.

“The land is ours, the house is ours, the sky is ours,” she said. “They can’t kick us out from here.”

But the younger generation is less certain about the future of Palestinian life in Hawara.

Sadin, a 16-year-old relative who lives in the house with Khmous, has trouble sleeping through the night now and is scared to walk along the streets of Hawara. She wants to join her father in Ohio.

“Before I didn’t accept the idea of leaving,” she said, fidgeting with her hands, which were decorated with blue henna. “But what happened pushed me to make a decision.”

Hamed Abdullah is having similar thoughts. For now he still works at his father’s battery shop. But if the bypass road bankrupts the business, he may reapply for a visa to join his sister in the U.S., where he could put his computer science degree to use.

Abu Assad, who runs the hilltop resort, said that if the situation doesn’t improve, he may have no choice but to leave with his children, who range in age from 4 to 27. He might move to Venezuela, where his mother is from and much of his family has citizenship. The entrepreneur, who previously ran a car business, never worried that Smotrich was literally going to send bulldozers into Hawara and raze the town. That, he said, wasn’t necessary.

“I don’t think they will come and throw us out,” Assad said as he smoked a cigarette in the resort office. “But they’re encouraging the settlers to attack, and do what they want, so that we leave on our own.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO