How Indians made London, a new book has the story

From the mid 16th-century, Indians in London were not only building the city, but also shaping the course of the nationalist movement in India.

Chatterjee’s book traces the presence of Indians in London back to the mid-16th century, when a number of them travelled to the city as servants or by accident as part of Britain’s seafaring exploits.

Chatterjee’s book traces the presence of Indians in London back to the mid-16th century, when a number of them travelled to the city as servants or by accident as part of Britain’s seafaring exploits.In 2015, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Wembley Stadium in London, his counterpart David Cameron made a powerful statement: “One day, not far, a British Indian prime minister would have his shack at 10 Downing Street”.

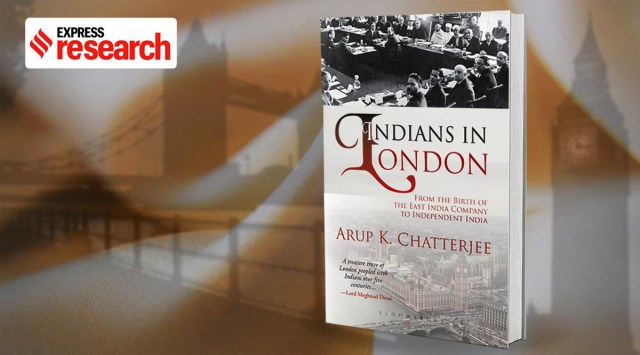

Cameron’s statement was noteworthy, given the significant presence of Indians in British society and politics today. “Britain today has over forty members in the House of Commons and the House of Lords from its South Asian community- a staggering figure by any standards,” writes Dr. Arup Chatterjee in his latest book, ‘Indians in London: From the birth of East India Company to Independent India’, published by Bloomsbury. He then moves five centuries back to comment on how most of London’s homes, its transport service, postal service, national insurance and a lot more were built by South Asian and Caribbean migrants. To document the presence of Indians in London, he says, is necessary to dismantle the myth of the city being white and impervious.

Chatterjee’s book traces the presence of Indians in London back to the mid-16th century, when a number of them travelled to the city as servants or by accident as part of Britain’s seafaring exploits. In the course of the next few centuries, Indians in London were not only building the city, but also shaping the course of the nationalist movement in India. In an interview with Indianexpress.com, Chatterjee spoke at length about the different categories of Indians in London and their experiences, the kind of gaze that the British had towards Indians, and how the city shaped the minds of the likes of Gandhi and Jinnah.

Excerpts from the interview:

Who were the Indians in London in the mid-16th century period, that is before the British empire in India was officially formed?

Dr. Arup Chatterjee: A majority of Indians in eighteenth-century London were lascars, or seafarers. Roughly three-fourth of Indians in sixteenth-century London were in the pre-lascar stage or the stage of servitude. It was not exactly slavery but somewhere between slavery and professional labour. England was never comfortable acknowledging itself as a slave-owning nation. Therefore, visible instutionalised slavery in England was lesser than in America. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Indian servants in London were practically slaves, for the lack of a better word. The remaining were explorers, or servants of European explorers. Many Indians in London were also part of England’s evangelical mission, which became the keystone of the seventeenth-century British Empire. Many Indians landed up in Britain because of the seafaring exploits that started in the 15th century with the ilk of Columbus and Vasco Da Gama. Many such Indians married Irish women or Britons of the lowest social category. Numerically, there were probably not more than a 1,000 Indians in seventeenth-century Britain. However, the number grew to over 10,000 in nineteenth-century Britain.

You write that a large number of servants went to London after the Battle of Plassey and the subsequent expansion of the British Empire as well. Why was this not called slavery? How was it different?

Dr. Arup Chatterjee: Britain was averse to acknowledging its informal institutions of slavery, such as household labour. Many Indians in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century London, and Indian ayahs in Victorian London, were household labourers or servants. Until the formation of institutions like Ayah’s Home (founded in the nineteenth century) or lascar welfare acts and policies, poor Indians in London had minimal rights. Early Indian servants practically owed their lives to their employers without whose permission they could not move.

‘George Clive and his Family with an Indian Maid.’ Painted by Joshua Reynolds, in 1765. Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. (Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

‘George Clive and his Family with an Indian Maid.’ Painted by Joshua Reynolds, in 1765. Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. (Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

An Indian called Julian was hanged at Tyburn, in the 1720s, for stealing 30 guineas from his employer. Julian had tried running away, like many Indian servants used to. These Indians had landed in London on the Company’s passes, either as lascars or indentured servants. Usually, the servants would make an attempt to return to India, after running away from London households. If caught, they were subjected to harsh punishments.

Those who managed to reach the dockyards were charged hefty sums of money to purchase their return to India. They would either sell off something very precious; at times, they perished on the streets of London. Since the late nineteenth century, many lascars and runaway servants became absorbed in the emerging Indian catering industry.

Why did you stick to just London and not all of Britain?

Dr. Arup Chatterjee: London is, of course, the economic, cultural and social capital of Britain. Nineteenth century-London was produced and reproduced as an imperial space and as a virtual commodity. The British empire wanted to trade this city as a global idea. That way, the world would be attracted to London, physically or virtually. Indians in London shows that this myth of the great hegemony of British imperialism and industry that sprung up around the City of London had been, nevertheless, penetrated by Indians. It is not realistic to decolonise Britain, but to say that London is a white city or purely an imperial centre, and that is how it is going to be imagined in centuries to come is also a ridiculous statement. The idea was to demonstrate that London can be decolonised from the mythology of an impenetrable, a myth that was promulgated largely during the Victorian regime.

I have plotted a map of about 200 Indian characters (historical protagonists) and their establishments to give readers a sample of the strength of the Indian settlement in London alone, until about the beginning of the twentieth century. If people from the Caribbean Islands, South America, Easter Europe and others start plotting their respective cultural presence in Victorian London, this entire hegemonic structure will effectively collapse.

‘Three Lascars of the “Viceroy of India,” standing Behind the Wheel of one of the Ship’s Tenders.’ Created by Marine Photo Service, in 1930s. Courtesy: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. (Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

‘Three Lascars of the “Viceroy of India,” standing Behind the Wheel of one of the Ship’s Tenders.’ Created by Marine Photo Service, in 1930s. Courtesy: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. (Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)We often create divisions between the external world and ourselves, say, between London and Mumbai. But these divisions are very arbitrary. The idea of a new India was midwifed by the consciousness of Indians in London. The London that we are talking about was rebuilt after 1666 when most of its buildings were mutilated in the great fire. £37 billion were spent in reconstructing London. This money came from the taxes that the East India Company was paying to the Crown. It came not only from India but several other colonies. However, by the end of the 18th century India was giving Britain £43.2 million every year. And in 1813, the EIC’s assets in India were evaluated at £300 billion (in today’s value). London was practically rebuilt with Indian money. The city was and remains a non-physical extension of India.

What is the kind of gaze that the British had towards the Indians?

Dr. Arup Chatterjee: Between 1550 and the 1750s, the gaze was often similar to that of watching an animal being slaughtered or being sanctified before the slaughter. Indian offenders were often hanged at the Tyburn, for petty offences. The story of the baptism of Peter Pope is a classic example that was unearthed in the 19th century. From the Victorian descriptions of Peter Pope’s baptism, that happened in December 1616, it is clear that he was treated like Shakespeare’s character Caliban. There was a very sharp division between the people who gazed at this Caliban-like-Indian and the more sophisticated people like the chaplains of the East India Company, the Archbishop of Canterbury. The ones gazing at Peter Pope were very numerous. London was going through a huge demographic shift in the early 16th century. A large part of the city’s population comprised Eastern Europeans, Dutch, French and German races, Latin Americans, Africans and Indians. These people constituted the crowd of traders, wanderers, bakers, ironsmiths, gunmakers, tailors, and so on, that would gaze on the likes of Peter Pope.

In the early 1700s, the East India Company started trading aggressively in Indian goods, bringing back a lot of costly wares such as hookahs, porcelain wares and chinaware. Trading with Mughal India, and Calcutta’s becoming the Company’s headquarter, facilitated greater interaction with Indian culture. By the 1750s, the colonial gaze became less crude. It was a culturally condescending gaze. After the Carnatic wars, and the Battles of Plassey and Buxar, Britons (and the French knew) had established, to themselves, their cultural superiority in India. Earlier they were traders and they were quite happy to trade with Mughal India. As a consequence, Calcutta was seen as a British invention. The fact that Calcutta’s foundations were laid down by the Portuguese and Armenians in the 1640s gets overshadowed. After 1764, when the Diwani of Bengal was transferred to the British, Company Nabobs (nawabs) started looking at themselves as more Mughal than the Mughals. Since they felt they could adopt Mughal culture better than Indians, they believed themselves to be racially superior. Subsequently, the colonial gaze became increasingly malignant.

You write that from sometime in the mid-19th century, the Little Bengal in London began shaping the empire in ways that have gone largely unacknowledged. Why do you say so?

Dr. Arup Chatterjee: Since the 1780s, the area around Bayswater, Baker Street, South Kensington and Holborn was concentrated with Indian immigrants. These areas were pejoratively called Asia Minor and Little Bengal. After the Battle of Seringapatam in 1799, many Britons returned to London as ‘nabobs’, a pejorative term for people who smoked hookahs, munched curries, were generally very rich and much hated in Britain. These people sought to recreate Bengal in London. The Victorian era began with the wrong decision of Britain going to war with Afghanistan in 1838. In 1839, Britain went to war with China over opium. Combined with the horrors of the Great Rebellion of 1857, the British public would be haunted by the memories of imperial bloodshed in the East. Seen psychologically, these informal districts named as Asia Minor or Little Bengal was an effort to marginalise the dark Easterly elements lurking in the epicentre of the Empire, in London.

This so-called Asia Minor was a threshold for modern Indians to enter London. Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Dwarkanath Tagore, Ardaseer Cursetji Wadia, followed by Indian barristers, civil servants, diplomats, students and many modern groups of Indians came to Victorian London. Their presence also determined what kind of policies were to take shape in India. Doubtless, the experiences of Indians in London between 1840 and 1900 would shape the future of the British in India and independent India itself.

Why did you choose to keep aside one segment specifically for the Armenians in a book on Indians in London?

Dr. Arup Chatterjee: India has always been multicultural. Yet, regrettably, we have given disproportionate importance to the British when it came to acknowledging and historicizing our so-called colonial masters. The enslavement of a particular variety of the Indian mind that wrote our older history textbooks is staggering. Why indeed do we lament—perhaps even unknowingly vindicate—our British colonisation alone, when there were the Dutch, the Danish, the Portuguese, and even Russians and Swedes trying to colonize India? Evidence suggests that it is far-fetched to think the British alone could have built Calcutta. The city was redeveloped by the British through indirect Dutch support, but all that was preceded by the Portuguese and the Armenians. The Armenians, were a remarkable group of people, very skilled in trade and unafraid to experiment with religious conversions. They lived in three principalities—Murshidabad, Surat and some Portuguese controlled areas in the south. Calcutta drew great benefits from their trade. Joseph Amin, one of the Indians in eighteenth-century London, came from Calcutta. He identified himself as an Armenian, an Indian and an Anglophile. He made a great impression on Edmund Burke, who would later lead the impeachment of Warren Hastings. When Emin visited London, in the mid-1750s, there were other Indian Armenians based there already. This history also needs to be told.

By the time nationalist leaders like Gandhi and Jinnah visited London, were Britons making distinctions between them and the stereotype of the Indians who were mostly servants in the city? Or what was the perception that Britons had towards Indian nationalist leaders?

Dr. Arup Chatterjee: By the 1880s and 90s, when Gandhi and Jinnah visited London, the city had seen the likes of Roy, the Wadia Brothers, Tagore (senior), Keshub Chunder Sen, and a whole host of barristers, civil servants and luminaries, that included Dadabhai Naoroji, Mancherji Bhownaggree, W.C. Bonnerjee and Romesh Chunder Dutt. Naoroji, a Liberal Party member, became the first Indian member of the House of Commons in 1892. Three years later, Bhownaggree, a Conservative candidate, became the second Indian to enter the House. The third was Shapurji Saklatwala, who entered the House in the early 1920s.

‘Gandhi Meets with Charlie Chaplin at the home of Dr. Kaitial in Canning Town, London (Sarojini Naidu on the right).’ From September 22, 1931. Photograph taken during Gandhi’s visit to the Second Rond Table Conference, in 1931. ( Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons).

‘Gandhi Meets with Charlie Chaplin at the home of Dr. Kaitial in Canning Town, London (Sarojini Naidu on the right).’ From September 22, 1931. Photograph taken during Gandhi’s visit to the Second Rond Table Conference, in 1931. ( Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons).

By the end of the nineteenth century, over two thousand Indian students were in London. The Inns of Court, in central London, were familiar destinations for Indians like Gandhi and Jinnah. Victorian London perceived India quite differently, and indeed with a great deal of respect. When we see the kind of respect with which Londoners listened to the speeches of Lalmohan Ghosh, the Liberal party candidate for Deptford in 1885, or the oratory of Swami Vivekananda, in 1895, it is evident that the city was rather welcoming towards Indians and Indian ideas.

After 1879, Edwin Arnold’s The Light of Asia and F. Max Muller’s Sacred Books of the East (which also featured the Upanishads) had created tremendous awareness about Indic spirituality. Bonnerjee’s palatial mansion at Croydon, named ‘Kidderpore’, Dutt’s scholarly contributions to the intellectual atmosphere of University College, and Naoroji’s fiery theses on the Indian ‘drain of wealth’ created a great stir in London’s social life.

Thus, when Gandhi or Jinnah imitated English manners, clothing and culture, in Victorian London, they were also imitating Indian precedents; and these hybrid idiosyncrasies that they picked up in London would distinguish them from the core ideologies of British imperialism. London did colonise their minds, but, eventually, empowered them to decolonise themselves and territories back home. For some, like Jinnah, that decolonisation was somewhat of a mirage or relegated to superficial things.

For others, like Gandhi, it was a sanatan and civilisational approach that, paradoxically, dawned on him in London. M.K. Gandhi and Subhas Bose, in particular—but also a whole host of Indian nationalists in London, including A.O. Hume, Annie Besant, V.K. Menon, Rabindranath Tagore and others I have mentioned—exposed to Indian eyes the many other Wests lurking within London. These people effectively mined the so-called imperial city to unearth a whole new cosmopolitan civilisation which they then enshrined as a new idea of India. As London remains in India’s debt, India too owes a few debts to that other London, which we rarely try to excavate from the archives of our collective memory.

Must Read

Buzzing Now

Mar 01: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05