Abstract

The existing shortage of therapists and caregivers assisting physically disabled individuals at home is expected to increase and become serious problem in the near future. The patient population needing physical rehabilitation of the upper extremity is also constantly increasing. Robotic devices have the potential to address this problem as noted by the results of recent research studies. However, the availability of these devices in clinical settings is limited, leaving plenty of room for improvement. The purpose of this paper is to document a review of robotic devices for upper limb rehabilitation including those in developing phase in order to provide a comprehensive reference about existing solutions and facilitate the development of new and improved devices. In particular the following issues are discussed: application field, target group, type of assistance, mechanical design, control strategy and clinical evaluation. This paper also includes a comprehensive, tabulated comparison of technical solutions implemented in various systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An individual’s capacity to move is necessary to perform basic activities of daily living (ADL). Movement disorders significantly reduce a patient’s quality of life. Disorders of the upper extremities specifically limit the independence of affected subjects. Fortunately, there are various approaches to restore the functionality of the upper extremity, e.g., orthoses, functional electrical stimulation, and physical therapy. Positive outcome of physical rehabilitation, in the case of neurologically based disorders, depends heavily on: onset, duration, intensity and task-orientation of the training [1, 2], as well as the patient’s health condition, attention and effort [3]. Intense repetitions of coordinated motor activities constitute a significant burden for the therapists assisting patients. In addition and due to economical reasons, the duration of primary rehabilitation is getting shorter and shorter [4]. These problems will probably exacerbate in the future as life expectancy continues to increase accompanied by the prevalence of both moderate and severe motor disabilities in the elderly population [5] and consequently increasing their need of physical assistance. To counteract these problems, prevailing research studies present a wide variety of devices specifically assisting physical rehabilitation. Robotic devices with the ability to perform repetitive tasks on patients are among these technically advanced devices. In fact, robotic devices are already used in clinical practice as well as clinical evaluation. However, considering the number of devices described in the literature, so far only a few of them have succeeded to target the subject group — for more details see Table 1. Furthermore, it seems that the outcome of the use of devices already in clinical practice is not as positive as expected [3]. New solutions are being considered. Most of the literature reviews on robotic devices for upper extremity rehabilitation (e.g. [6, 7]) concentrate on devices that have already undergone clinical evaluation. Gopura and Kiguchi [8] compared the mechanical design of selected robotic devices for upper extremity rehabilitation. However, no other publication presents a summary of different robotic solutions for upper extremity rehabilitation, including those being in the development phase. An assessment of different technical solutions would provide developers of robotic devices for upper limb rehabilitation an evaluation of solutions that have already been considered, and thus learn from successes as well as shortfalls from other research teams. Hence, a comparison of various robotic devices would facilitate the development of new and improved devices for robotic upper limb rehabilitation. The aim of this paper is to summarize existing technical solutions for physical therapy of the upper limb.

The survey of robotic devices is comprised of advanced technology systems. As defined in this report, the design of advance technology systems includes sensors, actuators, and control units; purely mechanical solutions are excluded from this survey. Although the research team made an effort to identify as many systems as possible, it is reasonable to acknowledge that many systems are left unmentioned. Nevertheless, this documentation is intended to be a valuable source of information for engineers, scientists and physiotherapists working on new solutions for physical rehabilitation.

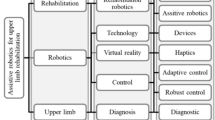

The survey

Scope of the survey

At the outset, the research team identified literature associated with the subject matter based on searches in PubMed, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), Science Direct and Google Scholar databases using various combinations of the following keywords: upper extremity, arm, hand, rehabilitation, therapy, training, movement, motion, assistance, support, robot, robotized, robotic, mechatronic, and motorized. Additionally, referenced literature from the selected publications was included in the survey as well. The information obtained from this literature compendium is supplemented with the data acquired from professional caregivers and manufacturers’ catalogs and websites, as well as direct communications with rehabilitation professionals, manufacturers and patients. Over 120 systems are summarized and compared in Table 1; this tabulated summary constitutes the reference for information provided in subsequent sections. As previously mentioned, the scope of this report is generally limited to the devices that support or retrain movement or manipulation abilities of disabled individuals. This survey excludes systems developed for movement assessment, occupational purposes or boosting physical abilities of healthy people. We however considered some academic, not yet specialized systems, supporting upper-extremity movements, especially if they have potential to be used for rehabilitation purposes (e.g. CADEN-7[97]). This survey also excludes devices that substitute movements of the disabled extremity but do not replace the movement itself (e.g. wheelchair mounted manipulators or autonomous robots). Although these devices improve the patient’s quality of life, they differ significantly from systems described in this survey and constitute a separate category of devices. Some companies (e.g. CSMi Computer Sports Medicine, Inc.; Biodex Medical Systems, Inc.; BTE Technologies, Inc.) manufacture sensorized equipment for rehabilitation of various joints and muscles and whose principle of operation often resembles that of exercising devices found at fitness centers. Those devices are used mainly to strengthen muscles and joints and provide some predefined resistance (e.g. isotonic, isometric or isokinetic exercises) or active force (e.g. continuous passive motion exercises). These devices also constitute a different category from the systems included in this survey because their functions are performed along a predefined operation pathway. Although difficult to clearly identify, the aforementioned were also excluded from this review.

Throughout this report, the term “number of degrees of freedom (DOF)” describes the sum of all independent movements (i.e. displacements or rotations) that can be performed in all the joints of the device. The number of DOF is defined in order to determine the exact position and orientation of all segments of the device. Also, some sections in this report are supplemented by an explanation of the most important terminology for readers who are not familiar with the technical vocabulary.

Application field and target group

A description of the specific field of application for upper limb rehabilitation devices often determines solutions for which the device itself may be applied. Upper-extremity rehabilitation involves actions that stimulate patients’ independence and quality of life. Two main application fields of robotic devices stand out: support to perform some ADLs (e.g. by power assistance or tremor suppression) and providing physical training (therapy). Although there is a significant need for powered devices supporting basic ADL at home, there are only a few of such devices proposed so far (see sixth column in Table 1). This is mainly due to technical and economical restrictions. Such devices should significantly improve the lives of their users, otherwise patients become dissatisfied and discontinue their use shortly after. They should be also safe, easily to handle and inexpensive. Portability is also often expected from devices assisting patients to perform basic ADL; in such cases the amount of available energy is limited by the capacity to store energy. Furthermore, if the device is supposed to support movements of multiple joints, the number of needed actuators increases as well as the weight of the device. Therefore, the number of portable actuated devices supporting upper extremity movements is typically low. Instead, purely mechanical solutions are used for that purpose. A few examples of portable powered devices for upper extremity assistance used in daily living are PowerGrip system (Broaden Horizons, Inc., USA) and a system proposed by Hasegawa, et al. [98] (both for grasp assistance), as well as WOTAS orthosis [99] and a system proposed by Loureiro, et al. [100] (both for tremor suppression). However, portability is not always necessary. Often, especially after a stroke or a spinal cord injury, disorders of the upper extremity are accompanied by lower extremity disabilities. These scenarios are typically characterized by immobilized conditions and require a wheelchair. Therefore, many systems assisting upper limb movements are installed close to the patient (e.g. modular wheelchair-mounted system MUNDUS[101]).

Another group of the robotic devices used for rehabilitation purposes, much bigger than the group of devices supporting basic ADLs, constitute devices providing physical therapy. These may be designed for either specialized therapeutic institutes or home-based conditions. A vast majority of these devices may be used only at therapeutic institutes since they require supervised assistance from qualified personnel. Their price is often prohibitive for personal use due to their complexity. The patient demand for home-based therapy is expected to increase. Along this context, the concept of the Gloreha system (Idrogenet srl) is provided in two versions: (1) a more complex and more adaptable professional version intended for use at hospitals and rehabilitation centers and (2) a simplified low-cost version intended for patient use at home. However, according to Dijkers, et al. [102], many therapists may stop using devices if set-up takes more than 5 minutes. Thus new developed devices for physical training should be intuitive, easy and fast to set-up and have a reasonable price.

Stroke is the most common cause among diseases and injuries for upper limb movement disorders. It is estimated that by 2030, stroke will be the fourth leading cause of reduced disability-adjusted life-years (DALY) in western countries. DALY takes into account years of life lost due to premature death as wells as years of life lived in less than full health [103]. Other causes include traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury and injuries to motoneurons, as well as certain neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, Guillain-Barre syndrome, essential tremor and Parkinson’s disease. Currently proposed robotic systems for upper limb rehabilitation are typically tested on stroke patients. Only a fraction of these systems are investigated on subjects suffering from other diseases (see last column of Table 1).

Type of assistance

The most important terminology introduced in this section is explained in Table 2. Devices for upper limb rehabilitation may provide different types of motion assistance: active, passive, haptic and coaching. Active devices provide active motion assistance and possess at least one actuator, thus they are able to produce movement of the upper-extremity. Most of the devices discussed in this survey are active (see Table 1). Such assistance of movements is required if patient is too weak to perform specific exercises. However, even with active devices, an exercise is considered passive when a patient’s effort is not required. For example, devices providing continuous passive motion exercises are active, but those exercises are categorized as passive because the subject remains inactive while the device actively moves the joint through a controlled range of motion. It is not necessary to apply active assistance to resist patient’s movement, to increase patient’s force or to ensure the patient is following the desired trajectory. Instead, passive devices may be applied that are equipped with actuators providing resistive force only (i.e. brakes). Such actuators consume less energy and are cheaper than the heavier actuators for active assistance. Devices using only resistive actuators include both devices for physical therapy, e.g. MEM-MRB[104] and PLEMO[105], and systems for tremor suppression, e.g. WOTAS[99] orthosis and a system proposed by Loureiro, et al. [100].

Haptic devices constitute another group of systems interacting with the user through the sense of touch. Haptic devices are similarly classified as either active or passive, depending on their type of actuator. In this report, haptic devices are independently categorized because their main function is not to cause or resist movement but rather to provide tactile sensation to the user. Other non-actuated devices for upper limb rehabilitation do not generate any forces but provide different feedback. These systems are labeled coaching devices throughout this report. Because coaching devices are sensorized, they serve as input interface for interaction with therapeutic games in virtual reality (VR) (e.g. T-WREX[106], ArmeoSpring from Hocoma AG) or for telerehabilitation (i.e. remotely supervised therapy). Coaching systems using video-based motion recognition (e.g. Microsoft Kinect) would also belong to this category if it were not for their lack of any mechanical part in contact with the patient. Therefore, these systems will not be further discussed in this survey.

Passive and non-actuated systems are less complex, safer and cheaper than their active counterparts. However, they are often modified in the development process with more active characteristics. Still, the main characteristic that identifies a non-actuated or passive device is the lack of the ability to perform movement; they may be an option for continuation of the rehabilitation process, rather than for training of people with significant movement disorders at an early stage of rehabilitation.

Mechanical design

The most important terminology introduced in this section is explained in Table 3. When comparing the mechanical structure of robotic devices for movement rehabilitation often two categories of devices are considered: end-effector-based and exoskeleton-based. The difference between the two categories is how the movement is transferred from the device to the patient’s upper extremity. End-effector-based devices contact the patient’s limb only at its most distal part that is attached to patient’s upper extremity (i.e. end effector). Movements of the end effector change the position of the upper limb to which it is attached. However, segments of the upper extremity create a mechanical chain. Thus, movements of the end effector also indirectly change the position of other segments of the patient’s body as well. Compared to end effectors, exoskeleton-based devices have a mechanical structure that mirrors the skeletal structure of patient’s limb. Therefore movement in the particular joint of the device directly produces a movement of the specific joint of the limb.

The advantage of the end-effector-based systems is their simpler structure and thus less complicated control algorithms. However, it is difficult to isolate specific movements of a particular joint because these systems produce complex movements. The manipulator allows up to six unique movements (i.e. 3 rotations and 3 translations). Control of the movements of the patients upper limb is possible only if the sum of possible anatomical movements of patient arm in all assisted joints is limited to six. Increasing the number of defined movements for the same position of the end-point of the manipulator results in redundant configurations of the patient’s arm, thus inducing risk of injuries and complicated control algorithms.

The typical end-effector-based systems include serial manipulators (e.g. MIT Manus[107] - Figure 1B, ACRE[108]), parallel (e.g. CRAMER[109] and a system proposed by Takaiwa and Noritsugu [110], both for wrist rehabilitation), and cable-driven robots (e.g. NeReBot[111] - Figure 1C, MACARM[112]). The mechanical structure of HandCARE[113] may be also recognized as the series of end-effector-based cable-driven robots, each of which induce movement of one finger. In this system a clutch system allows independent movement of each finger using only one actuator.

Examples of mechanical structures of robotic devices for upper limb rehabilitation. A: ARM Guide - simple system using linear bearing to modify orientation [136]; B: InMotion ARM - end-effector-based commercial system [133]; C: NeReBot - cable-driven robot, Ⓒ2007 IEEE. Reprinted, with permission, from [111]; D: ArmeoPower - exoskeleton-based commercial system (courtesy of Hocoma AG).

Application of the exoskeleton-based approach allows for independent and concurrent control of particular movement of patient’s arm in many joints, even if the overall number of assisted movements is higher than six. However, in order to avoid patient injury, it is necessary to adjust lengths of particular segments of the manipulator to the lengths of the segments of the patient arm. Therefore setting-up such device for a particular patient, especially if the device has many segments, may take a significant amount of time. Furthermore, the position of the center of rotation of many joints of human body, especially of the shoulder complex [114], may change significantly during movement. Special mechanisms are necessary to ensure patient safety and comfort when an exoskeleton-based robot assists the movements of these joints [114]. For this reason, the mechanical and control algorithm complexity of such devices is usually significantly higher than of the end-effector-based devices. The complexity escalates as the number of DOF increases.

In case of systems for the rehabilitation of the whole limb the number of DOF reaches nine (ESTEC exoskeleton[115]) or ten (IntelliArm[116]). Some systems for fingers or hand rehabilitation have an even higher number of DOF. Examples include the system proposed by Hasegawa, et al. with eleven DOF [98] and the hand exoskeleton developed at the Technical University (TU) of Berlin with twenty DOF [117]. Even at such a high number of DOF some of these devices still remain wearable (i.e. the user is able to walk within a limited area due to connections to power source and control unit, e.g. ESTEC and hand exoskeleton developed at the TU Berlin) or portable (i.e. the area within which the user may walk is not limited, e.g. the system proposed by Hasegawa).

Apart from purely exoskeleton- or end-effector-based devices, there are many systems combining a few approaches. In the ArmeoSpring system (Hocoma AG) for example, only the distal part – comprising the elbow, forearm and wrist – is designed as an exoskeleton. Therefore the limb posture is statically fully determined (as in exoskeleton-based systems) and the shoulder joint is not constrained, allowing easy individual system adaptation to different patients. A similar concept was applied in Biomimetic Orthosis for the Neurorehabilitation of the Elbow and Shoulder – BONES[118]. In that case, a parallel robot consisting of passive sliding rods pivoting with respect to a fixed frame provides shoulder movements. Such application of sliding rods allows internal/external rotation of the arm without any circular bearing element. The distal part allowing for flexing/extending the elbow resembles the exoskeleton structure. In the MIME-RiceWrist rehabilitation system [119] the end-effector-based MIME[120] system for shoulder and elbow rehabilitation is integrated with the parallel wrist mechanism used in the MAHI exoskeleton (known as RiceWrist[119]).

Another example is the 6 DOF Gentle/S[121] system allowing for relatively large reaching movements (three actuated DOF of the end-effector-based commercial haptic interface HapticMaster, Moog in the Netherlands BV [122]) and arbitrary positioning of the hand (connection mechanism with three passive DOF). The Gentle/S system was further supplemented with a three-active-DOF hand exoskeleton to allow grasp and release movements. This new nine DOF system is known as Gentle/G[123].

The HEnRiE[124] is a similar system based on the Gentle/S system. In addition to the three active DOF of HapticMaster, HEnRiE includes a connection mechanism with two passive DOF for positioning of the hand and grasping device (two parallelogram mechanisms allowing parallel opening and closing of fingers attachments) with only one active DOF.

Some systems combine more than one robot at the same time. This approach may be considered as the combination of end-effector-approach, where only the most distal parts of robots are attached to the patient’s upper limb, with the exoskeleton-based approach, where movements of few segments are directly controlled at the same time. Use of two robots to control the movements of the limb may allow for mimicking the operations performed by therapist using two hands. Examples of systems using two-robot-concept include REHAROB[125] (using two six-DOF manipulators), iPAM[126] and UMH[127] (both having six DOF in total). Researchers at the University of Twente, in Enschede, Netherlands, made an attempt to use two HapticMaster systems to provide coordinated bilateral arm training, but limitations in hardware and software caused the virtual exercise to behave differently to the real-life [128]. In some cases industrial robots have also been used. The REHAROB uses IRB 140 and IRB 1400H from ABB Ltd., while MIME[120] uses PUMA 560 robot. In general, industrial robots reduce costs; however, such robots have significantly higher impedance than the human upper limb and, according to Krebs, et al. [129], should not be in close physical contact with patients. Therefore most of the robots used for the rehabilitation of the upper limb are designed with a low intrinsic impedance. Some of those devices are also back drivable (e.g. HWARD[130] and RehabExos[131]), meaning that the patient’s force is able to cause movement of those devices when they are in passive state. Back-drivability further increases safety of the patient because the device does not constrain patient movements. It also allows for using the device as an assessment tool to measure patient’s range of motion.

The majority of the devices presented in Table 1 allow movements in three dimensions; however there are also planar robots, i.e., systems allowing movements only on a specified plane (e.g. MEMOS[132] and PLEMO[105]). Also the MIT Manus system initially allowed movements only on one plane [107]. Subsequently, an anti-gravity module added possibility to perform vertical movements [133] (Figure 1B). Designing the device as a planar robot reduces the range of movements that can be exercised for particular joint. It also reduces the cost of the device. Furthermore, when the working plane is well selected, the range of training motion may suffice in most of therapeutic scenarios. Some of such planar devices allow changes in the working space between horizontal and vertical (Braccio di Ferro[134]) or even almost freely selecting the working plane (e.g. PLEMO and Hybrid-PLEMO[135]). It further increases the range of possible exercise scenarios while keeping the cost of the device at a minimum.

In the ARM Guide[136] (Figure 1A) and ARC-MIME[137] systems, with which patients practice reaching movements, the working space is limited to linear movements because the forearm typically follows a straight-line trajectory. However the orientation of the slide that assists forearm movements can be adjusted to reach multiple workspace regions and fit different scenarios.

Modularity and reconfigurability are concepts that could reduce therapy costs by adopting therapeutic devices for various disabilities or stages in patient recovery. However there are still only a few systems using these concepts. For example, InMotion ARM robot (the commercial version of MIT Manus, previously called InMotion 2.0) from Interactive Motion Technologies, Inc., may be extended by InMotion WRIST robot (previously InMotion 3.0), developed at MIT [138] as a stand-alone system, and InMotion HAND add-on module (previously InMotion 5.0) for grasp and release training. Another example of modular system is MUNDUS[101], consisting of various modules that may be included depending on the patient condition, starting from muscle weakness to complete lost of residual muscle function. For example as command input residual voluntary muscular activation, head/eye motion, or brain signals may be used. However, this system’s complexity might make commercialization of the device very difficult.

A very interesting solution was implemented in the Universal Haptic Drive (UHD)[139]. It has only two DOF and, depending on the chosen configuration, it can train either shoulder and elbow during reaching tasks or forearm (flexion/extension) and wrist. For the latter setting option, it is also possible to select a flexion/extension or pronation/supination training for the wrist. See Figure 2 for an explanation of anatomical terms used for description of upper limb motion.

Main movements (degrees of freedom) of the upper extremity. 1: arm flexion/extension; 2: arm adduction/abduction; 3: arm internal(medial)/external(lateral) rotation; 4: elbow flexion/extension; 5: forearm pronation/supination; 6: wrist flexion/extension; 7: wrist adduction(ulnar deviation)/abduction(radial deviation); 8: hand grasp/release.

Actuation and power transmission

The most important terminology introduced in this section is explained in Table 4. Traditionally, energy to the actuators is provided in three forms: electric current, hydraulic fluid or pneumatic pressure. The selection of the energy source determines the type of actuators used in the system. Most of the devices for upper extremity rehabilitation use electric actuators but there are also other systems with pneumatic and hydraulic actuators. The electric actuators are most common because of their ease to provide and store electrical energy as well as their relatively higher power. Various types and sizes of electrical motors and servomotors are currently commercially available. Some authors (e.g. Caldwell and Tsagarakis [140]) argue that electric actuators are too heavy, compared to their pneumatic counterparts, and their impedance is too high to be used in rehabilitation applications. However, the relatively high power-to-weight ratio of pneumatic actuators is achieved by neglecting the weight of the power source. Adding an elastic element in series with the actuator may also mitigate the high impedance of electric motors. This concept lead to the development of the so called Series Elastic Actuators (SEAs). SEAs decrease inertia and user interface impedance to provide an accurate and stable force control [141], thus increasing the safety of the patient. The disadvantage of application with an elastic element is the lower functional bandwidth. Still, the field of rehabilitation does not usually require high bandwidths. SEAs with electric motors are investigated in MARIONET[142] and UHD[139] systems, as well as in systems proposed by Vanderniepen, et al. (referred to as MACCEPA actuators) [143] and Rosati, et al. [144].

A few systems use pneumatic actuators. Pneumatic actuators are lighter and have lower inherent impedance than the electric counterparts. Because such actuators require pneumatic pressure, the system is generally either stationary (e.g. Pneu-WREX[145]), its service area is limited (e.g. ASSIST[146]) or the compressor is installed on the patient’s wheelchair (e.g. system proposed by Lucas, et al. [147]). Special type of pneumatic actuators, called Pneumatic Artificial Muscles (PAMs), Pneumatic Muscle Actuators or McKibben type actuators are often used in rehabilitation robotics (e.g. Salford Arm Rehabilitation Exoskeleton[148] or system proposed by Kobayashi and Nozaki [149]). Such actuators consist of an internal bladder surrounded by braided mesh shell with flexible, but non-extensible, threads. When the bladder is pressurized, the actuator increases its diameter and shortens according to its volume, thus providing tension at its ends [150]. Due to such physical configuration, PAMs’ weight is generally light compared to other actuators, but also have slow and non-linear dynamic response (especially large PAMs), in consequence they are not practical for clinical rehabilitation scenarios [131, 151]. In addition, at least two actuators are necessary in order to provide antagonistic movements due to the unidirectional contracting. The ASSIST system has a special type of PAM with rotary pneumatic actuators that allows bending movements [146].

A total of four systems using hydraulic actuators were identified in this survey. All four of them are not standard and use actuators developed specially for that purpose. Reasons to evade industrial hydraulic actuators include weight, impedance, fluid leakages and difficulties to provide fluid. Large, noisy systems are usually necessary for that purpose. Mono-and bi-articular types of Hydraulic Bilateral Servo Actuators (HBSAs) are used in the wheelchair-mounted exoskeleton proposed by Umemura, et al. [152]. Miniaturized and flexible fluidic actuators (FFA) were applied in the elbow orthosis proposed by Pylatiuk, et al. [153]. Hydraulic SEAs are used in two other systems: the Dampace system [154] is equipped with powered hydraulic disk brakes; the Limpact system [155], developed by the same group, uses an active rotational Hydro-Elastic Actuator (rHEA).

In passive systems, it is often desired to modify the amount of resistance during the exercise. This modification increases the resistance when the patient departs from the desired trajectory or to provide haptic feedback for VR interactions. In existing systems, different solutions for provision of adjustable resistive force have been implemented. Powered hydraulic brakes, for example, controlled by electromotors in a SEA are used in Dampace system [154]. Magnetic particle brakes are used in ARM Guide[136] (Figure 1A), in its successor ARC-MIME[137] to resist other than longitudinal movements of the forearm, and in the device for training of multi-finger twist motion proposed by Scherer, et al. [156]. A few groups have also investigated the application of brakes incorporating magnetorheological (MRF brakes) and electrorheological fluids (ERF brakes). These fluids change their rheological properties (i.e. viscosity) depending on the applied magnetic or electric field, respectively. Thanks to those properties it is possible to achieve brakes with high-performance (with rapid and repeatable brake torque) [105]. MRF brakes are used in MRAGES[157] and MEM-MRB[104] systems. ERF brakes are used in PLEMO[105] and MR_CHIROD v.2[158] systems. The same group that developed the PLEMO also proposed ERF clutches to control the force provided by an electric motor in active systems. Such an actuation system was implemented in EMUL[159], Robotherapist[160] and Hybrid-PLEMO[135] devices.

The natural actuators of body muscles can be used instead of external actuators. For this purpose, an electrical stimulation of the muscles leading to their contraction can be applied. This specific electrical stimulation is known as Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES). FES significantly reduces the weight of the device. From a therapeutic point of view, FES allows patients to exercise muscles, improving muscle bulk and strength and preventing muscular atrophy [161]. It has been also shown that FES, complemented by conventional physiotherapy, may enhance the rehabilitation outcome [162]. However, FES may cause strong involuntary muscle contractions and can be painful for patient. Furthermore, it is difficult to control movements using FES because of the non-linear force characteristic of contracting muscles, muscles fatigue and dependency of the achieved contraction on the quality of the contact between stimulating electrodes and the body tissue. There are two commercial systems using FES for upper limb rehabilitation: Ness H200 (Bioness, Inc., US) and NeuroMove (Zynex Medical, Inc., US). Two other systems combining FES with assistive force were proposed by Freeman, et al. [163] and Li, et al. [164].

When selecting actuators, it is also important to consider their location, especially with exoskeleton-based mechanical structures. The actuators can be placed distally, close to the joints on which they actuate (e.g. ArmeoPower system, Figure 1D). This specification simplifies the power transmission by using direct drives. However, it increases the weight of the distal part of the device and inertia and makes it more difficult to control the system. On the other hand, locating the actuators in the proximal part of the device, often in the part that remains constrained, reduces the weight and inertia of the distal part. However, a power transmission mechanism complicates the mechanical structure and may lead to difficulties with control due to friction. For example, the same group who developed InMotion HAND system proposed an earlier prototype of the hand module with eight active DOF and cable-driven mechanism for power transmission. The friction in that mechanism and its level of complexity was too high for clinical scenarios [165]. Nevertheless, there are systems, in which power transmission using cables and gear drives was successfully applied, like for example CADEN-7[97] and SUEFUL-7[166].

Control signals

The most important terminology introduced in this section is explained in Table 5. Various signals may be used as control input of the device. Switches are often used to simplify design. Examples include the PowerGrip system from Broaden Horizons, Inc., hand held triggers (e.g. FES based system for grasp assistance proposed by Nathan, et al. [167]) and a joystick (e.g.MULOS[168]). Most of the systems having more complex control strategies use either kinematic, dynamic or a mix of both input signals (see Table 1 for a comparison). The type of the signal used as control input is partially determined by the low-level control strategy and vice-versa. In some cases, signals provided by actuator encoders (concerning position or torque) may be directly used for control purposes. However, usually torque measured by the encoder is a sum of the torque exerted by the user on device and internal torques in the device. Therefore, for better control of forces between patient and device, it is useful to apply additional sensors that will measure those forces directly.

Some systems use surface electromyography (sEMG) as an input signal, which provides information about intention of the person to perform particular movement. Therefore it is possible to detect and support it. Most of such systems support elbow movements, as sEMG signals from muscles controlling this joints (i.e. biceps brachii or triceps brachii) are relatively easily measured. Among proposed solutions are both stationary (e.g. systems proposed by Rosen, et al. [169] and Kiguchi, et al. [170]) and portable systems (e.g. systems proposed by Ögce and Özyalçin [171] and Pylatiuk, et al. [153]). So far the most successful of those systems is the one DOF portable orthosis developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, US [172]. The system successfully sustained clinical trials, received FDA approval and was commercialized as Myomo e100 system (Myomo, Inc.) [173]. Examples of sEMG-controlled systems supporting movements of other joints include those proposed by Kiguchi, et al. [114] for shoulder rehabilitation, W-EXOS[174] for forearm and wrist rehabilitation, PolyJbot[175] for wrist rehabilitation, SUEFUL-7[166] exoskeleton for whole limb (excluding fingers) movement assistance, TU Berlin Hand Exoskeleton[117] for fingers rehabilitation, as well as 11-DOF portable orthosis for grasp assistance proposed by Hasegawa, et al. [98]. The sEMG signals from the contralateral healthy limb have been also used to control movements of the affected one (see system proposed by Li, et al. [176]). The concept of using movements of the not affected limb to control motion of the affected one has been also implemented in Bi-Manu-Track system (Reha-Stim, Germany), ARMOR exoskeleton [177] and device proposed by Kawasaki, et al. [178]. Using the other limb to control the affected one is especially useful during rehabilitation after stroke. In cases of hemiparesis (or hemiplegia), often only one side of the body is affected.

In some systems also contact-less movement detection methods have been used. For example, Ding, et al. [179] proposed a system to assist the load of arbitrary selected muscles using motion capture systems in order to calculate the actual muscle force.

Feedback to the user

Different types of feedback may be provided to the user, among them: visual, tactile, audio and in the form of electrical stimulation. Some systems, for example those proposed by Lam, et al. [180] and Nathan, et al. [167], use vibrational stimulation of the muscle tendons to support their contraction. It was also suggested that providing tactile feedback to flexor and extensor surfaces of the skin at the appropriate location could produce more naturalistic movements and improve clinical outcomes [3]. Some other systems combine other types of the feedback, for example system proposed by Casellato, et al. [181] combines visual and haptic feedback to improve motor performance of children with dystonia.

A significant number of systems provide training in virtual reality (VR) scenarios. VR provides a much more interesting training surrounding to the patient, compared to the typically available conditions presented in therapeutic units. Furthermore, it allows for fast modification of training scenarios, increasing patient attention and motivation to perform the exercise. Therefore it may also improve positive outcome of the therapy. It also adapts the system for various patients in a very short time frame and restarts the task if the object was dropped or misplaced. Haptic devices are especially well suited for provision of therapy in VR because they provide an impression of manipulating the virtual objects. Some groups developed own versions of haptic systems. For example Takahashi, et al. [182] proposed haptic device for arm rehabilitation, which can apply multiple types of force including resistance, assistance, elasticity, viscosity and friction. Other examples are: a two DOF Haptic Interface for Finger Exercise (HAFI), which provides rehabilitation of only one finger at a time [183]; a force reflecting glove, named MRAGES, using magneto-rheological fluid [157]; MR_CHIROD v.2, a one DOF grasp exercise device for functional magnetic resonance imaging [158] and force-feedback glove Rutgers Master II-ND[184], developed at the Rutgers University (Piscataway, US) and used in hand therapy scenarios (e.g. [185–187]).

Many groups have investigated application of a few of commercial haptic devices for rehabilitation of upper extremity. Among such haptic interfaces are: - HapticMaster incorporated for example in Gentle/S[121] (for other examples see Table 1),- in-parallel robots Phantom Omni and Premium (Geomagic, Inc., US) - used e.g. in experiments performed by Casellato, et al. [181], Brewer, et al. [188], and Xydas and Louca [189], - parallel robot Falcon (Novint Technology, Inc., US) - used in My Scrivener system for hand writing training (Obslap Research LLC, US) [190],- force-feedback glove CyberGrasp (CyberGlove Systems LLC,US) - used among others in therapeutic scenarios investigated by Adamovich, et al. [191, 192].

Because the entertainment industry have recently introduced many new devices to capture motion of the healthy people for interaction with VR-based games, it may be expected that soon some of those devices will be also adapted for rehabilitation purposes, providing so called “serious games”.

Control strategy

The most important terminology introduced in this section is explained in Table 6. Following the example of Marchal-Crespo and Reinkensmeyer [193] we will consider “high-” and “low-level” control strategies used by rehabilitation robots. “High-level” control algorithms are explicitly designed to provoke motor plasticity whereas “low-level” strategies control the force, position, impedance or admittance factors of the “high-level” control strategies.

“High-level” control strategies

There is a myriad of “high-level” control strategies for robotic movement training. This section briefly summarizes the classification of those strategies presented by Marchal-Crespo and Reinkensmeyer [193]. They identify four categorizes of control strategies: (a) assistive control, (b) challenge-based control, (c) haptic stimulation, and (d) non-contacting coaching. Although some systems may fall into a few of these categorizes, this classification well illustrates main notions in the “high-level” control of robotic devices for upper limb rehabilitation. Those control strategies in most cases correspond also to active, passive, haptic and coaching types of motion assistance described before.

The assistive control strategy makes tasks safer and easier to accomplish, allowing more repetitions. There are four types of assistive strategies: impedance-based, counterbalance-based, EMG-based and performance-based adaptive control. In the impedance-based strategy, the patient follows a particular trajectory. The device does not intervene as long as the patient follows this trajectory. However, as the patient leaves the trajectory, the device produces a restoring force that increases along with the deviation from the desired trajectory. Often some margin of deviation from allowed trajectory is accepted before restoring force is provided. Counterbalance-based strategies provide a partial, passive or active weight counterbalance to a limb, those making the exercises easier, as the amount of force needed to move the limb against the gravity may be significantly reduced. EMG-based approach uses the patient’s own sEMG signals to either trigger or proportionally control the assistance. Both of those approaches encourage patients’ effort. However, the triggered method is more susceptible to slacking, as the patient may learn to provide only the amount of force needed to trigger the assistance. Finally, the performance-based adaptive control strategies monitor the performance of the patient and adapt some aspects of the assistance (e.g. force, stiffness, time, path) according to the current performance of the patient, as well as performance during particular number of preceding task repetitions.

Challenge-based control strategies

fall into three groups: resistive, amplifying error and constraint-induced. The resistive strategies resist the desired movements, those increasing the effort and attention of the patient. The error amplifying strategies are based on the theory that faster improvements are achieved when error is increased [194]. Therefore they track the deviations from the desired trajectories and either increase the observed kinematic error or amplify its visual representation on the screen. The constraint-induced robotic rehabilitation strategy, similarly to conventional constraint-induced therapy, promotes the use of the affected limb by constraining the not affected one.

Haptic stimulation strategies

make use of haptic devices described above, providing tactile sensation for interactions with virtual reality objects. These strategies support training of basic ADLs in safe conditions and without long set-up. They provide alternate tasks in various environments, attracting attention and providing conditions for implicit learning.

Non-contacting coaching strategy

is applied in systems that do not contact participants but rather monitor their activity and provide instructions to the patient. Instructions indicate how to perform particular activities or what should be improved. Since such devices do not contact the patient, they are not applicable for systems described herein. However, this category may be extended to include also some sensorized, but not-actuated exoskeletons, such as the gravity balancing orthosis T-WREX[106].

“Low-level” control strategies

Different “low-level” control strategies are combined to develop “high-level” rehabilitation strategies. Many “low-level” control strategies may be proposed during following stages of development of a robotic rehabilitation device. This report provides a short description of basic approaches and does not include a comprehensive comparison of “low-level” control strategies. General books on control engineering provide a more detailed description, in addition to articles referenced in Table 1.

As the rehabilitation robots interact with human body, it is necessary to consider the manipulator and patient as a coupled mechanical system. The application of force or position control is not enough to ensure appropriate and safe dynamic interaction between human and robot [195]. Other control strategies, such as impedance or admittance control are implemented in most of the robots for upper limb rehabilitation. In the impedance control approach the motion of the limb is measured and the robot provides the corresponding force feedback, whereas in the admittance control approach the force exerted by the user is measured, and the device generates the corresponding displacement. The advantages and disadvantages of the impedance and admittance control systems are complementary [196]. In general, robots with impedance control have stable interaction but poor accuracy in free-space due to friction. This low accuracy can be improved using inner loop torque sensors and low-friction joints or direct drives. Admittance control in contrast compensates the mass and friction of the device and provides higher accuracy in non-contact tasks, but can be unstable during dynamic interactions. This problem is eliminated using SEAs. Devices using admittance control require also high transmission ratios (e.g. harmonic drives) for precise motion control [196]. In some cases both of theses approaches may be combined together. Impedance control strategy has been implemented for example in MIT Manus[107] (Figure 1B) and L-Exos exoskeleton [197], admittance control is found in MEMOS[132] and iPAM[126].

Clinical evidence

Clinical studies

As previously discussed, there has been a significant effort during last two decades to improve the design and control strategy of robotic rehabilitation devices. Yet, less has been done to prove the efficacy of such systems in rehabilitation settings. Although the results of clinical evaluation of therapy applying robots are still sparse, the problem is slowly being recognized. The focus in rehabilitation robotics is starting to move from technical laboratories to clinics. References to clinical trials in which robotic rehabilitation devices have been used are provided in the last column of Table 1. The classification of clinical trials used in this review is summarized in Table 7.

From the developer and manufacturer’s point of view, there may be at least three objectives in performing clinical trials. The first one is to address regulatory requirements. The devices described in this review are considered medical devices in most countries and as such the studies proving device efficacy and safety may be required before they are authorized for distribution. Although in some cases the exemption from providing the clinical data may be granted, e.g. if the device is recognized as low risk (Class 1 device in the European Union and the USA) or if equivalent device has been already approved for commercialization, the clinical data may be required by health insurance authorities in order to provide reimbursement. In this case the objective of the trial is to obtain a proof of clinical or financial benefit of the use of the device as compared to the existing modes of therapy. The third objective of clinical trials is to provide the professional community with the clinical evidence of device’s efficacy. Although, the three objectives may seem to be similar, the requirements are not the same, therefore when designing a clinical trial it should be considered if the obtained results will allow to satisfy requirements of those three objectives. For the study design requirements to satisfy the marketing and reimbursement objectives, we refer the readers to the legal regulations in the country of interest. Whereas, for a review on the process to design a clinical train with sound scientific results we refer to Lo [198].

From the clinical point of view, the objective of the clinical study may be different than to validate a particular device. For therapists the robotic device is a tool that provides a therapy protocol rather than an end product [198], thus they are rather interested in responses to questions concerning optimal training intensity, disorders for which such form of training may be beneficial, and whether robotic therapy should substitute or complement other forms of therapy.

This survey includes a search into the US Clinical Trials database (http://clinicaltrials.gov/) from October 2013 using a combination of keywords: robotic, robot, therapy and rehabilitation. This is an web-based database existing since 1997 and maintained by the US National Library of Medicine at the National Institutes of Health. Under the American Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA) of 2007 all the applicable clinical trials (what concerns category II and III/IV studies in our survey) performed in the USA and starting after 2007 have to be registered in this database. However, it includes also some category I studies and many other studies performed in other countries. Results of this search identified 197 clinical trials out of which 62 are relevant to this survey. The selected trials are divided into two categories. The main objective of the first category is to proof the efficacy or safety of the device, therefore there was either no control group or a control group was undergoing the standard form of the therapy. The main objective of the second category is to determine a more efficient form of the therapy. In the latter category, the participants were assigned to groups undergoing similar forms of therapy, but at different intensities, using various devices or undergoing various forms of therapy in different order. A total of 31 studies aim at device safety or efficacy validation while 27 address better forms of therapy. A total of four trials were excluded. The objective of these trials was to validate other forms of therapy; devices described in this review have only been used as a reference. As indicated in Figure 3, the number of participants enrolled in studies for therapy improvement significantly increased during last three years compared to the number of participants in the device safety/efficacy validation studies. This suggests that the objective of the studies changes from validating forms of therapy to finding optimal applications methods. This survey identified a total of 21 devices out of the 58 clinical studies. However, it was not possible to determine the robotic device in 11 studies. Surprisingly, almost only stroke survivors (54 studies) were enrolled. In the remaining four studies subjects with cerebral palsy, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury and rotator cuff tear were involved.

Outcomes of clinical studies

Many questions concerning effective robotic upper-limb rehabilitation still remain unanswered. One of the most important reasons is that the most effective interventions to optimize neural plasticity are still not clear and it is not possible to implement them in rehabilitation robotics [7]. The other is that the results of the clinical controlled trials remains limited and those already available are difficult to compare with each other [7, 193]. It is also questionable which measures should be used to evaluate the effects of therapy and which outcome should be compared: short-term or long-term. Scales based on evaluation of abilities influencing the quality of life are often not objective enough, since they rely on therapist expertise.

Although it is not possible to indicate the best control strategy for the rehabilitation, there is already some evidence showing that some strategies are producing better outcomes, whereas some can even decrease recovery time compared to possible non-robotic strategies [193].

Most accepted theories about robotic rehabilitation

are clear: The goal of the rehabilitation training is not only to maximize the number of repetition but to maximize the patients attention and effort as well [3]. The monotonous exercises provide worse retention of a skill compared with alternate training [7]. Adaptive therapy and assistance as needed provide better results as fixed pattern therapy [193]. Robotic therapy can possibly decrease recovery if it encourages slacking since the patient may decrease effort and attention due to the use of adaptive algorithm [193]. Because learning is error based, faster improvement may be achieved when error is increased [194]. Implicit learning, allowing patients to learn skills without awareness, may result in greater learning effect [7]. Many functional gains are more dependent on wrist and hand movements than on the mobility of shoulder and elbow [7]. It is not the maximal voluntary contraction (strength of the muscles) but appropriately timed activity of agonist and antagonist (coordination of the movements) that significantly improve the rehabilitation [3].

As previously stated, the objective of this report is not to review the results of clinical studies performed so far. A detailed review of clinical studies is referenced in other publications [7, 198–202]. The most important results are still worth mentioning. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the trials performed in stroke patients suggest that robotic training improves motor impairment and strength but do not improve ability to perform ADLs [199, 200]. The results of the first large randomized multicenter study in which training with MIT-Manus robotic system have been compared with intensive therapist-provided therapy and usual care have revealed that there is no significant difference in the outcomes of the two intensive forms of the therapy [203]. Thus the most important advantage of robotic systems is their ability to provide intensive repetitive training without over-burdening therapists [204]. Another advantage is the ability to provide more motivating training context, by means of a computer gaming environment with quantitative feedback to motivate practice [205]. Concerning cost-effectiveness of robotic rehabilitation, the results of the previously mentioned multicenter trial have shown that when the total cost of the therapy is compared, i.e. the cost of the therapy plus the cost of all the other health care use, the costs of the two forms of the intensive therapy (i.e. robot-assisted and therapist-provided) are similar [203]. However, the cost of technology is expected to decrease, as opposed to the cost of human labor. Therefore cost-effective advantage toward robot-therapy may be expected [198].

Conclusions

Due to population changes, shortage of professional therapists, and the increasing scientific and technical potential, many research groups have proposed devices with the potential to facilitate the rehabilitation process. Many devices for upper limb rehabilitation have already been proposed. A vast majority of these proposed devices are technically advanced and are designed for clinical settings. However, there is still significant need to improve efficiency and reduce cost of home-based devices for therapy and ADLs assistance. The effectiveness of robotic over conventional therapy is arguable and the best therapy strategy is still not clear. The situation may change soon, because more and more devices are being commercialized and more scientific results will be available. It may encourage next groups to propose their own solutions. Developing new devices and improving those already in the market will be easier, when taking advantage from the already existing solutions. We hope that this survey will help to navigate between those solutions and select best of them, thus facilitating development of new and better systems for robotic upper limb rehabilitation. We also hope that it will be a valuable source of information for all the professionals looking for a comprehensive reference.

References

Platz T: Evidenzbasierte Armrehabilitation: Eine systematische Literaturübersicht [Evidence-based arm rehabilitation–a systematic review of the literature]. Nervenarzt 2003,74(10):841-849. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00115-003-1549-7] [] 10.1007/s00115-003-1549-7

Feys H, Weerdt WD, Verbeke G, Steck GC, Capiau C, Kiekens C, Dejaeger E, Hoydonck GV, Vermeersch G, Cras P: Early and repetitive stimulation of the arm can substantially improve the long-term outcome after stroke: a 5-year follow-up study of a randomized trial. Stroke 2004,35(4):924-929. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000121645.44752.f7] [] 10.1161/01.STR.0000121645.44752.f7

Patton J, Small SL, Rymer WZ: Functional restoration for the stroke survivor: informing the efforts of engineers. Top Stroke Rehabil 2008,15(6):521-541. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1310/tsr1506-521] [] 10.1310/tsr1506-521

Richards L, Hanson C, Wellborn M, Sethi A: Driving motor recovery after stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil 2008,15(5):397-411. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1310/tsr1505-397] [] 10.1310/tsr1505-397

WHO: The global burden of disease: 2004 Update. World Health Organization (WHO). 2008. [http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GBD_report_2004update_full.pdf] []

Riener R, Nef T, Colombo G: Robot-aided neurorehabilitation of the upper extremities. Med Biol Eng Comput 2005, 43: 2-10. 10.1007/BF02345116

Brewer BR, McDowell SK, Worthen-Chaudhari LC: Poststroke upper extremity rehabilitation: a review of robotic systems and clinical results. Top Stroke Rehabil 2007,14(6):22-44. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1310/tsr1406-22] [] 10.1310/tsr1406-22

Gopura RARC, Kiguchi K: Mechanical designs of active upper-limb exoskeleton robots: State-of-the-art and design difficulties. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics ICORR. Kyoto, Japan; 2009:178-187.

Cheng HS, Ju MS, Lin CCK: Improving elbow torque output of stroke patients with assistive torque controlled by EMG signals. J Biomech Eng 2003,125(6):881-886. 10.1115/1.1634284

Cozens JA: Robotic assistance of an active upper limb exercise in neurologically impaired patients. Rehabil Eng, IEEE Trans 1999,7(2):254-256. 10.1109/86.769416

Mavroidis C, Nikitczuk J, Weinberg B, Danaher G, Jensen K, Pelletier P, Prugnarola J, Stuart R, Arango R, Leahey M, Pavone R, Provo A, Yasevac D: Smart portable rehabilitation devices. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2005, 2: 18. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1743-0003-2-18] []

Song R, yu Tong K, Hu X, Li L: Assistive control system using continuous myoelectric signal in robot-aided arm training for patients after stroke. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 2008,16(4):371-379. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2008.926707] []

Hu X, Tong KY, Song R, Tsang VS, Leung PO, Li L: Variation of muscle coactivation patterns in chronic stroke during robot-assisted elbow training. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007,88(8):1022-1029. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2007.05.006] [] 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.05.006

Song R, Tong KY, Hu XL, Tsang SF, Li L: The therapeutic effects of myoelectrically controlled robotic system for persons after stroke–a pilot study. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2006, 1: 4945-4948. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/IEMBS.2006.260186] []

Kung PC, Ju MS, Lin CCK: Design of a forearm rehabilitation robot. In Proc. IEEE 10th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics ICORR. Noordwijk, Netherlands; 2007:228-233.

Kung PC, Lin CCK, Ju MS, Chen SM: Time course of abnormal synergies of stroke patients treated and assessed by a neuro-rehabilitation robot. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics ICORR. Kyoto, Japan; 2009:12-17.

Colombo R, Pisano F, Mazzone A, Delconte C, Micera S, Carrozza MC, Dario P, Minuco G: Design strategies to improve patient motivation during robot-aided rehabilitation. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2007, 4: 3. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1743-0003-4-3] []

Hu XL, Tong KY, Song R, Zheng XJ, Lui KH, Leung WWF, Ng S, Au-Yeung SSY: Quantitative evaluation of motor functional recovery process in chronic stroke patients during robot-assisted wrist training. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2009,19(4):639-650. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jelekin.2008.04.002] [] 10.1016/j.jelekin.2008.04.002

Hu XL, Tong KY, Song R, Zheng XJ, Leung WWF: A comparison between electromyography-driven robot and passive motion device on wrist rehabilitation for chronic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2009,23(8):837-846. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1545968309338191] [] 10.1177/1545968309338191

Sale P, Lombardi V, Franceschini M: Hand robotics rehabilitation: feasibility and preliminary results of a robotic treatment in patients with hemiparesis. Stroke Res Treat 2012, 2012: 820931. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/820931] []

Chen M, Ho SK, Zhou HF, Pang PMK, Hu XL, Ng DTW, Tong KY: Interactive rehabilitation robot for hand function training. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics ICORR. Kyoto, Japan; 2009:777-780.

Turner M, Gomez D, Tremblay M, Cutkosky M: Preliminary tests of an arm-grounded haptic feedback device in telemanipulation. In Proc. of the ASME Dynamic Systems and Control Division. Anaheim, CA; 1998:145-149.

Ertas IH, Hocaoglu E, Barkana DE, Patoglu V: Finger exoskeleton for treatment of tendon injuries. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics ICORR. Kyoto, Japan; 2009:194-201.

Fuxiang Z: An Embedded Control Platform of a Continuous Passive Motion Machine for Injured Fingers. In Rehabilitation Robotics. Edited by: Kommu SS. Vienna, Austria: I-Tech Education Publishing; 2007:579-606.

Vanoglio F, Luisa A, Garofali F, Mora C: Evaluation of the effectiveness of Gloreha (Hand Rehabilitation Glove) on hemiplegic patients. Pilot study. In XIII Congress of Italian Society of Neurorehabilitation, 18-20 April. Italy: Bari; 2013.

Parrinello I, Faletti S, Santus G: Use of a continuous passive motion device for hand rehabilitation: clinical trial on neurological patients. In 41 National Congress of Italian Society of Medicine and Physical Rehabilitation, 14-16 October. Rome, Italy; 2013.

Varalta V, Smania N, Geroin C, Fonte C, Gandolfi M, Picelli A, Munari D, Ianes P, Montemezzi G, La Marchina E: Effects of passive rehabilitation of the upper limb with robotic device Gloreha on visual-spatial and attentive exploration capacities of patients with stroke issues. In XIII Congress of Italian Society of Neurorehabilitation, 18-20 April. Bari, Italy; 2013.

Ho NSK, Tong KY, Hu XL, Fung KL, Wei XJ, Rong W, Susanto EA: An EMG-driven exoskeleton hand robotic training device on chronic stroke subjects: task training system for stroke rehabilitation. IEEE Int Conf Rehabil Robot; Boston, MA 2011, 2011: 5975340. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ICORR.2011.5975340] []

Schabowsky CN, Godfrey SB, Holley RJ, Lum PS, Development and pilot testing of HEXORR: hand EXOskeleton rehabilitation robot. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2010, 7: 36. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1743-0003-7-36] []

Kline T, Kamper D, Schmit B: Control system for pneumatically controlled glove to assist in grasp activities. In Proc. 9th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics ICORR. Chicago, IL; 2005:78-81.

Mulas M, Folgheraiter M, Gini G: An EMG-controlled exoskeleton for hand rehabilitation. In Proc. 9th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics ICORR. Chicago, IL; 2005:371-374.

Hesse S, Kuhlmann H, Wilk J, Tomelleri C, Kirker SGB: A new electromechanical trainer for sensorimotor rehabilitation of paralysed fingers: a case series in chronic and acute stroke patients. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2008, 5: 21. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1743-0003-5-21] []

Rotella MF, Reuther KE, Hofmann CL, Hage EB, BuSha BF: An Orthotic Hand-Assistive Exoskeleton for Actuated Pinch and Grasp. In Bioengineering Conference, IEEE 35th Annual Northeast. Boston, MA; 2009:1-2. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/NEBC.2009.4967693] []

Sarakoglou I, Tsagarakis NG, Caldwell DG: Occupational and physical therapy using a hand exoskeleton based exerciser. In Proc. IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). Sendai, Japan; 2004:2973-2978.

Tong KY, Ho SK, Pang PK, Hu XL, Tam WK, Fung KL, Wei XJ, Chen PN, Chen M: An intention driven hand functions task training robotic system. In Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. Buenos Aires, Argentina; 2010:3406-3409. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/IEMBS.2010.5627930] []

Wege A, Hommel G: Development and control of a hand exoskeleton for rehabilitation of hand injuries. In Intelligent Robots and Systems, (IROS 2005). 2005 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on. Edmonton, Canada; 2005:3046-3051.

Worsnopp TT, Peshkin MA, Colgate JE, Kamper DG: An Actuated Finger Exoskeleton for Hand Rehabilitation Following Stroke. In Proc. IEEE 10th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics ICORR. Noordwijk, Netherlands; 2007:896-901.

Xing K, Xu Q, He J, Wang Y, Liu Z, Huang X: A wearable device for repetitive hand therapy. In Proc. 2nd IEEE RAS & EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics BioRob. Scottsdale, AZ; 2008:919-923.

Ellis MD, Sukal T, DeMott T, Dewald JPA: ACT 3D exercise targets gravity-induced discoordination and improves reaching work area in individuals with stroke. In Proc. IEEE 10th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics ICORR. Noordwijk, Netherlands; 2007:890-895.

Kahn LE, Lum PS, Rymer WZ, Reinkensmeyer DJ: Robot-assisted movement training for the stroke-impaired arm: Does it matter what the robot does? J Rehabil Res Dev 2006,43(5):619-630. 10.1682/JRRD.2005.03.0056

Chang JJ, Tung WL, Wu WL, Huang MH, Su FC: Effects of robot-aided bilateral force-induced isokinetic arm training combined with conventional rehabilitation on arm motor function in patients with chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007,88(10):1332-1338. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2007.07.016] [] 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.07.016

Volpe BT, Krebs HI, Hogan N, OTR LE, Diels C, Aisen M: A novel approach to stroke rehabilitation: robot-aided sensorimotor stimulation. Neurology 2000,54(10):1938-1944. 10.1212/WNL.54.10.1938

Rabadi M, Galgano M, Lynch D, Akerman M, Lesser M, Volpe B: A pilot study of activity-based therapy in the arm motor recovery post stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2008,22(12):1071-1082. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0269215508095358] [] 10.1177/0269215508095358

Ju MS, Lin CCK, Lin DH, Hwang IS, Chen SM: A rehabilitation robot with force-position hybrid fuzzy controller: hybrid fuzzy control of rehabilitation robot. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 2005,13(3):349-358. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2005.847354] [] 10.1109/TNSRE.2005.847354

Kiguchi K, Rahman MH, Sasaki M, Teramoto K: Development of a 3DOF mobile exoskeleton robot for human upper-limb motion assist. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2008,56(8):678-691. [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6V16-4R8MDRP-1/2/7d307e7bbef3e5958a6960e3da652723] [] 10.1016/j.robot.2007.11.007

Rosati G, Gallina P, Masiero S, Rossi A: Design of a new 5 d.o.f. wire-based robot for rehabilitation. In Proc. 9th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics ICORR. Chicago, IL; 2005:430-433.

Colombo R, Sterpi I, Mazzone A, Delconte C, Minuco G, Pisano F: Measuring changes of movement dynamics during robot-aided neurorehabilitation of stroke patients. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 2010, 18: 75-85. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2009.2028831] []

Lum PS, Burgar CG, Shor PC, Majmundar M, der Loos MV: Robot-assisted movement training compared with conventional therapy techniques for the rehabilitation of upper-limb motor function after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002,83(7):952-959. 10.1053/apmr.2001.33101

Lum PS, Burgar CG, der Loos MV, Shor PC, Majmundar M, Yap R: MIME robotic device for upper-limb neurorehabilitation in subacute stroke subjects: A follow-up study. J Rehabil Res Dev 2006,43(5):631-642. 10.1682/JRRD.2005.02.0044

Lum PS, Burgar CG, Shor PC: Evidence for improved muscle activation patterns after retraining of reaching movements with the MIME robotic system in subjects with post-stroke hemiparesis. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 2004,12(2):186-194. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2004.827225] [] 10.1109/TNSRE.2004.827225

Moubarak S, Pham M, Pajdla T, Redarce T: Design Results of an Upper Extremity Exoskeleton. In Proc. 4th European Conference of the International Federation for Medical and Biological Engineering. Antwerp, Belgium; 2008.

Masiero S, Celia A, Rosati G, Armani M: Robotic-assisted rehabilitation of the upper limb after acute stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007,88(2):142-149. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2006.10.032] [] 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.10.032

Masiero S, Armani M, Rosati G: Upper-limb robot-assisted therapy in rehabilitation of acute stroke patients: focused review and results of new randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Res Dev 2011,48(4):355-366. 10.1682/JRRD.2010.04.0063

Fazekas G, Horvath M, Troznai T, Toth A: Robot-mediated upper limb physiotherapy for patients with spastic hemiparesis: a preliminary study. J Rehabil Med 2007,39(7):580-582. [http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/mjl/sreh/2007/00000039/00000007/art00013] [] 10.2340/16501977-0087

Hesse S, Schulte-Tigges G, Konrad M, Bardeleben A, Werner C: Robot-assisted arm trainer for the passive and active practice of bilateral forearm and wrist movements in hemiparetic subjects. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003,84(6):915-920. 10.1016/S0003-9993(02)04954-7

Hesse S, Werner C, Pohl M, Rueckriem S, Mehrholz J, Lingnau ML: Computerized arm training improves the motor control of the severely affected arm after stroke: a single-blinded randomized trial in two centers. Stroke 2005,36(9):1960-1966. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000177865.37334.ce] [] 10.1161/01.STR.0000177865.37334.ce

Allington J, Spencer SJ, Klein J, Buell M, Reinkensmeyer DJ, Bobrow J: Supinator Extender (SUE): a pneumatically actuated robot for forearm/wrist rehabilitation after stroke. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2011, 2011: 1579-1582. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/IEMBS.2011.6090459] []

Cordo P, Lutsep H, Cordo L, Wright WG, Cacciatore T, Skoss R: Assisted movement with enhanced sensation (AMES): coupling motor and sensory to remediate motor deficits in chronic stroke patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2009, 23: 67-77. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1545968308317437] []

Koeneman EJ, Schultz RS, Wolf SL, Herring DE, Koeneman JB: A pneumatic muscle hand therapy device. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2004, 4: 2711-2713. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/IEMBS.2004.1403777] []

Kutner NG, Zhang R, Butler AJ, Wolf SL, Alberts JL: Quality-of-life change associated with robotic-assisted therapy to improve hand motor function in patients with subacute stroke: a randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther 2010,90(4):493-504. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20090160] [] 10.2522/ptj.20090160

Rosenstein L, Ridgel AL, Thota A, Samame B, Alberts JL: Effects of combined robotic therapy and repetitive-task practice on upper-extremity function in a patient with chronic stroke. Am J Occup Ther 2008, 62: 28-35. 10.5014/ajot.62.1.28

Frick EM, Alberts JL: Combined use of repetitive task practice and an assistive robotic device in a patient with subacute stroke. Phys Ther 2006,86(10):1378-1386. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20050149] [] 10.2522/ptj.20050149

Johnson M, Wisneski K, Anderson J, Nathan D, Smith R: Development of ADLER: The activities of daily living exercise robot. In 1st IEEE/RAS-EMBS Int. Conf. Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics, BioRob. Pisa, Italy; 2006:881-886.

Wisneski KJ, Johnson MJ: Quantifying kinematics of purposeful movements to real, imagined, or absent functional objects: implications for modelling trajectories for robot-assisted ADL tasks. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2007, 4: 7. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1743-0003-4-7] []

Pignolo L, Dolce G, Basta G, Lucca LF, Serra S, Sannita WG: Upper limb rehabilitation after stroke: ARAMIS a “robo-mechatronic” innovative approach and prototype. In 4th IEEE RAS & EMBS Int. Conf. Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob). Rome, Italy; 2012:1410-1414. [http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=6290868] []

Coote S, Murphy B, Harwin W, Stokes E: The effect of the GENTLE/s robot-mediated therapy system on arm function after stroke. Clin Rehabil 2008,22(5):395-405. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0269215507085060] [] 10.1177/0269215507085060

Culmer PR, Jackson AE, Makower SG, Cozens JA, Levesley MC, Mon-Williams M, Bhakta B: A novel robotic system for quantifying arm kinematics and kinetics: description and evaluation in therapist-assisted passive arm movements post-stroke. J Neurosci Methods 2011,197(2):259-269. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.03.004] [] 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.03.004

Kiguchi K, Kose Y, Hayashi Y: Task-oriented perception-assist for an upper-limb powerassist exoskeleton robot. In Proc. World Automation Congress (WAC). Kobe, Japan; 2010:1-6. [http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpls/abs_all.jsp?arnumber=5665314] []

Frisoli A, Bergamasco M, Borelli L, Montagner A, Greco G, Procopio C, Carboncini M, Rossi B: Robotic assisted rehabilitation in virtual reality with the L-EXOS. In Proc. of 7th ICDVRAT with ArtAbilitation. Maia, Portugal; 2008:253-260.

Carignan C, Tang J, Roderick S, Naylor M: A Configuration-Space Approach to Controlling a Rehabilitation Arm Exoskeleton. In Proc. IEEE 10th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics ICORR. Noordwijk, Netherlands; 2007:179-187.

Fluet GG, Qiu Q, Saleh S, Ramirez D, Adamovich S, Kelly D, Parikh H: Robot-assisted virtual rehabilitation (NJIT-RAVR) system for children with upper extremity hemiplegia. In Virtual Rehabilitation International Conference. Haifa, Israel; 2009:189-192.

Wolbrecht ET, Chan V, Reinkensmeyer DJ, Bobrow JE: Optimizing compliant, model-based robotic assistance to promote neurorehabilitation. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 2008,16(3):286-297. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2008.918389] []

Housman SJ, Le V, Rahman T, Sanchez RJ, Reinkensmeyer DJ: Arm-Training with T-WREX After Chronic Stroke: Preliminary Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. In Proc. IEEE 10th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics ICORR. Noordwijk, Netherlands; 2007:562-568.

Housman SJ, Scott KM, Reinkensmeyer DJ: A randomized controlled trial of gravity-supported, computer-enhanced arm exercise for individuals with severe hemiparesis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2009,23(5):505-514. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1545968308331148] [] 10.1177/1545968308331148

Sanchez RJ, Liu J, Rao S, Shah P, Smith R, Rahman T, Cramer SC, Bobrow JE, Reinkensmeyer DJ: Automating arm movement training following severe stroke: functional exercises with quantitative feedback in a gravity-reduced environment. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 2006,14(3):378-389. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2006.881553] []

Gupta A, O’Malley M: Design of a haptic arm exoskeleton for training and rehabilitation. IEEE ASME Trans Mechatronics 2006,11(3):280.

Lambercy O, Dovat L, Gassert R, Burdet E, Teo CL, Milner T: A haptic knob for rehabilitation of hand function. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 2007,15(3):356-366. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2007.903913] []

Casadio M, Giannoni P, Morasso P, Sanguineti V: A proof of concept study for the integration of robot therapy with physiotherapy in the treatment of stroke patients. Clin Rehabil 2009,23(3):217-228. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0269215508096759] [] 10.1177/0269215508096759

Carpinella I, Cattaneo D, Abuarqub S, Ferrarin M: Robot-based rehabilitation of the upper limbs in multiple sclerosis: feasibility and preliminary results. J Rehabil Med 2009,41(12):966-970. [http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/mjl/sreh/2009/00000041/00000012/art00004] [] 10.2340/16501977-0401

Casadio M, Sanguineti V, Solaro C, Morasso PG: A Haptic Robot Reveals the Adaptation Capability of Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis. Int J Rob Res 2007,26(11-12):1225-1233. 10.1177/0278364907084981

Vergaro E, Squeri V, Brichetto G, Casadio M, Morasso P, Solaro C, Sanguineti V: Adaptive robot training for the treatment of incoordination in Multiple Sclerosis. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2010, 7: 37. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1743-0003-7-37] []

Denève A, Moughamir S, Afilal L, Zaytoon J: Control system design of a 3-DOF upper limbs rehabilitation robot. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2008,89(2):202-214. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2007.07.006] [] 10.1016/j.cmpb.2007.07.006

Furuhashi Y, Nagasaki M, Aoki T, Morita Y, Ukai H, Matsui N: Development of rehabilitation support robot for personalized rehabilitation of upper limbs. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics ICORR. Kyoto, Japan; 2009:787-792.

Mathai A, Qiu Q: Incorporating Haptic Effects Into Three-Dimensional Virtual Environments to Train the Hemiparetic Upper Extremity. 2009. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2009.2028830] []

Ozawa T, Kikuchi T, Fukushima K, Akai H, Fukuda T, Tanida S, Fujikawa T, Kano S, Furusho J: Initial clinical tests for assessment models of synergy movements of stroke patients using PLEMO system with sensor grip device. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics ICORR. Kyoto, Japan; 2009:873-878.

Zhang H, Balasubramanian S, Wei R, Austin H, Buchanan S, Herman R, He J: RUPERT closed loop control design. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2010, 2010: 3686-3689. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/IEMBS.2010.5627647] []