|

| Jenni Fagan |

21 Books You Should Read This July

PART ONE

We Asked Lit Hub Contributors About What They're Looking Forward To

JULY 1, 2016

Pond, Claire-Louise Bennet (Riverhead Books)

Pond, Claire-Louise Bennet (Riverhead Books)

Claire-Louise Bennett’s debut novel captures our attention in whispers more than it does with bells or whistles. It’s not a “loud” novel. It doesn’t explain or announce itself. What action there is, is retold from the distance that memory provides—a distance bridged by way of second-guesses and digressions. Pond is the expression of a delightfully melancholic voice, as serious as it is funny, strange yet so very familiar. Readers will rush to find suitable comparisons—mine was Samuel Beckett—but Bennett successfully squirms away at every turn, and achieves something singularly her own. It’s a funny, smart book, that will relocate you for a time in the rural headspace of Bennett’s unnamed narrator, where you too will find yourself diving into the grimy ground of the everyday.

–Brad Johnson (Co-Manager Diesel Bookstore)

You Will Know Me, Megan Abbot (Little, Brown & Co)

You Will Know Me, Megan Abbot (Little, Brown & Co)

The Olympics start the first Friday in August, which means gymnastics will soon play an inexplicably prominent role in my life. I can’t say that I’ve ever watched a set of parents watching their daughter watch herself on the balance beam and thought, “somebody should set a murder mystery in that world,” but now that Megan Abbott has, with You Will Know Me, it strikes me as the best decision any writer has made in quite some time. Abbott is the author of The Fever and Dare Me, two favorites of literary-mystery lovers. Nobody captures the tortured relations between teens and adults quite like her. The high-tension world of competitive tumbling ought to be a perfect muse. And in any case this is the book that will help us all steel ourselves for that terrible, shimmering moment when the Károlyis first step onto the mat.

–Dwyer Murphy (Lit Hub contributor)

The Sunlight Pilgrims, Jenni Fagan (Hogarth)

The Sunlight Pilgrims, Jenni Fagan (Hogarth)

I can’t wait for Jenni Fagan’s The Sunlight Pilgrims. The Scottish author’s debut novel, The Panopticon, gave us a world in which the most destitute among us were forced into imprisonment. With this new work, Fagan once again offers a critique of our planet, this time from a more geological perspective. Different regions of the world are experiencing the worst winter on record. Our most vital social systems—economic exchange, healthcare—are barely in operation, and people are dying in the streets from the cold. It’s against this setting that Dylan, a refugee from London, must determine the best way to survive. If this book is as good as her first, we’re in for a thrilling and elegant work of post-apocalyptic fiction.

–Amy Brady (Lit Hub contributor)

Vaseline Buddha, Jung Young Moon (Deep Vellum, trans. Jung Yewon)

Vaseline Buddha, Jung Young Moon (Deep Vellum, trans. Jung Yewon)

Jung Young Moon’s Vaseline Buddha is a book about the act of writing. It opens with the narrator “unable to sleep, thinking vaguely that [he] would write a story.” In that first scene, he startles a would-be thief who is climbing up the gas pipes toward his bedroom window. The narrator wonders if it is his fault that the thief fell, wonders if there are some things in the world for which there is no fault. This opening “trivial” happening sets off a series of discursions, which some might disparage as literary navel-gazing or recollective free association, but which I found utterly fascinating and driven by an engaging voice. The book plays directly to the central questions of the act of writing: Should writing be driven by order or chaos? Should it structure the universe or reflect its seeming randomness? Is the imposition of form a virtue of a vice? On that front, it feels akin to writers like Gombrowicz and Beckett. Or maybe I’m just free associating? (Which I think the narrator of Vaseline Buddha would appreciate…)

–Tyler Malone (Lit Hub Contributing Editor,

The Scofield founder & Editor-in-Chief)

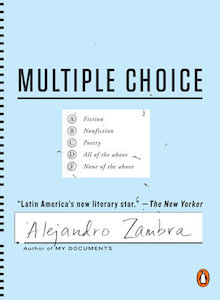

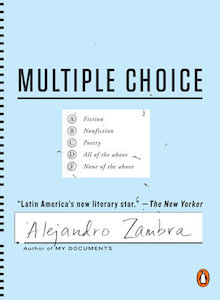

Multiple Choice, Alejandro Zambra (Penguin Books, trans. Megan McDowell)

I’ve never seen a writer attempt to structure a novel as a multiple choice test. Maybe it’s been done, or maybe Chilean author Alejandro Zambra is the first. Either way, it seems the perfect next step for an author who has always specialized in short, lyric works and who has increasingly embraced a hybrid genre of fiction that sort of acts like a novel but kind of looks like a short story collection. So, yes, he should further muddy the waters by turning this latest book into a standardized test that is made up of multiple choice questions that are in fact tiny, deconstructed narratives.

–Scott Esposito (Lit Hub contributor)

https://lithub.com/21-books-you-should-read-this-july/