Solstices and equinoxes: the reasons for the seasons

21 June 2018

For most of Australia, weather at the start and end of each year is generally warmer, and the middle of the year is cooler. Days are longer at the start and end of the year and shorter in the middle of the year. But why?

Australia's seasons: how many and when?

Four seasons?

Australia's weather year is typically divided into four seasons—based on the European model. Australian summer, autumn, winter and spring are defined in the following way:

- summer—the warmest three months: December, January and February;

- winter—the coolest three months: June, July and August; and

- spring and autumn—the three-month transition periods between summer and winter.

You can view maps of average daily maximum temperature for winter, spring, summer and autumn across Australia here.

Two seasons?

However, for Australia's northern tropics, there is little difference between average temperatures in 'winter' and 'summer', so the European four-season model isn't relevant there. In the tropics, each year is divided based on rainfall patterns:

- wet season—the months that generally include the heaviest rainfall (October–April); and

- dry season—the months that generally see less rain (May–September).

When the heavy rains arrive varies by year and location. For guidance on the timing of enough rainfall to stimulate plant growth after the dry season, check our Northern Rainfall Onset tool.

Three, five or six seasons?

Over thousands of years, Indigenous Australians have maintained local calendars that divide each year into seasons based on prevailing weather patterns and phenology (the annual phenomena of animal and plant life). You can see some of these calendars of our Indigenous Weather Knowledge website.

Solstices and equinoxes

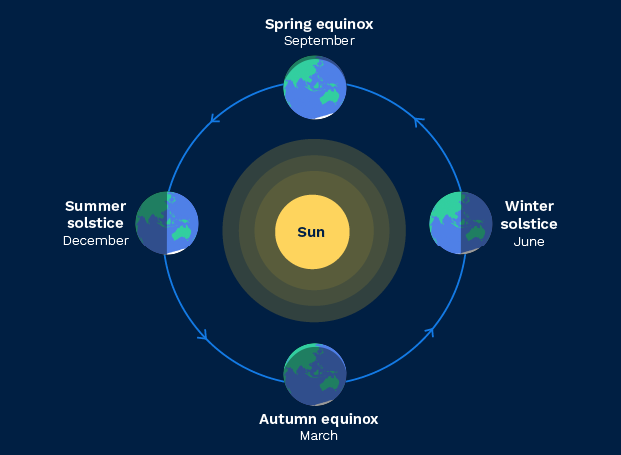

The annual variation in temperatures that is felt in the south of Australia is a result of the tilt of the Earth's rotation axis. We rotate around an 'axis'—a line from the north pole to the south pole, through the centre of the Earth—once every 24 hours, and we orbit the Sun once every year. Our rotation axis is tilted relative to the plane of our orbit around the Sun.

As we orbit the Sun, this tilt angles the southern hemisphere towards or away from the Sun at different times of the year.

Diagram: Earth has seasons because its axis is tilted. Earth rotates on its axis as it orbits the Sun, but the axis always points in the same direction.

From the surface of the Earth, this means the midday Sun appears further north or south in the sky depending on the time of year. It also means that each 24-hour rotation of Earth leaves Australia in daylight for more or less time, depending on where we are in our orbit around the Sun.

The solstices are the two times each year when the tilt in Earth's axis lines up most with the direction of the Sun, creating the maximum difference between daylight and nighttime hours.

The two equinoxes, in between, are when the tilt of Earth's axis is side-on to the Sun, so that our north and south poles are the same distance from the Sun. On those dates, the Sun appears directly above Earth's equator.

Spring equinox

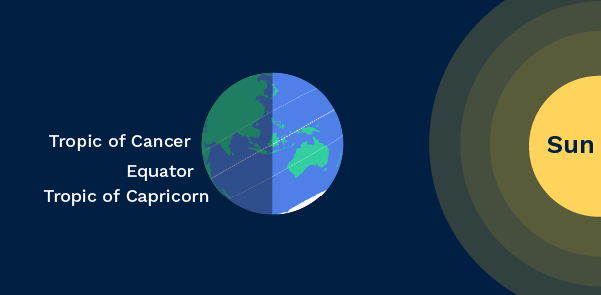

The date and time at which the centre of the Sun is directly over the equator in late September is called the equinox—from the Latin for 'equal night'. In the southern hemisphere, this marks the tipping point from days being shorter than nights, to days becoming longer than nights.

In fact, days and nights are equal in length (each 12 h) for the southern hemisphere two or three days before the technical spring equinox and most of Australia sees about 12 h 8 min. of daylight on the spring equinox itself. This is because our atmosphere refracts (bends) sunlight so that we can see the Sun just before it's risen in line with the horizon and just after it's passed below the level of the horizon at sunset.

Summer solstice

After the September equinox, the tilt of Earth's axis increasingly angles our south pole towards the Sun, so the Sun appears further south in the sky each day until it's over the Tropic of Capricorn around 22 December. This is the southern hemisphere's summer solstice.

The word 'solstice' comes from the Latin for 'sun-stopping'. At this point, the Sun stops appearing to move south each day. After this point, it appears further and further north in the sky each day.

Autumn equinox

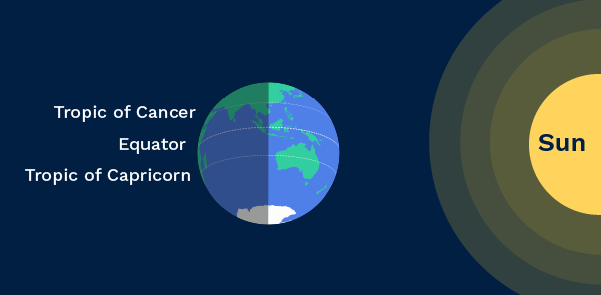

The Sun crosses over the equator again in late March, and days and nights are again the same length.

Winter solstice

After the March equinox, the tilt of Earth's axis angles the southern hemisphere further away from the Sun, so days in Australia become shorter than nights. The Sun continues to move north in the sky until it's over the Tropic of Cancer in late June—the southern hemisphere's winter solstice.

At the winter solstice, days are at their shortest. How many hours of daylight you'll see depends on your latitude (how far north or south you are). Hobart, for example, only sees around 9 hours of daylight at the winter solstice—but 15 hours of daylight at the summer solstice. Darwin, meanwhile, only varies between about 11½ hours of daylight at the winter solstice and about 12½ hours of daylight at the summer solstice. You can find sunrise and sunset times for your location for any date on the Geoscience Australia website.

The difference in average temperatures between December and June is also more pronounced in the 'temperate' south of Australia than in the tropical north. Southern parts of Australia therefore have distinct seasons—warmer, longer days in summer and colder, shorter days in winter. See our #AskBOM video on climate zones for more detail.

Lagging the solstice: when does the temperature change?

Our winter solstice is when we have the shortest days, and the least direct sunlight. During our winter, sunlight strikes the southern hemisphere at a steeper angle, spreading it over a larger area, meaning the ground receives less heat during winter than during summer. However, the winter solstice is not quite the coldest part of the year for Australia as a whole. The high 'heat capacity' of the oceans around us keeps us warm a little while longer. Likewise, the warmest part of the year for most of Australia lags behind the summer solstice. For much of southern Australia where the influence of the oceans is greatest, the coldest week of the year typically happens in July and the warmest week in late January or early February, some weeks after the solstice.

While some people and countries use the equinoxes and solstices to define the start of each season, for Australia it's a better fit to our temperatures to use 1 March, 1 June, 1 September and 1 December. Defining each season as a set of three whole calendar months is also convenient for compiling and presenting climate-based statistics.

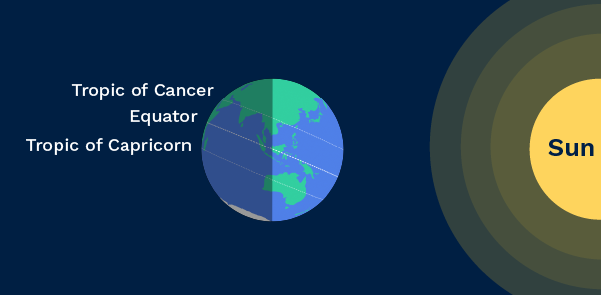

Subsolar point: the time of shortest shadows

As the Earth moves around the Sun, one side is always in daylight and there's always a location where the Sun is directly overhead.

This is known as the subsolar point – when the Sun's rays are perpendicular, or exactly 90°, to the ground. At this point in time the shadows of trees, buildings, people – any object – are at their shortest.

If you live in northern Australia (or any tropical area), your shadow almost disappears. But why does this only affect the tropical regions of the world?

As the Earth tilts, it also moves the subsolar point on the Earth's surface. This varies its position with the seasons, reaching north–south as far as the Tropic of Cancer (~23.5°N) in the north and the Tropic of Capricorn (~23.5°S) in the south. Tropical regions have two days per year where the sun is overhead. But you'll have a better chance at casting a (short) shadow in the generally sunnier conditions before Christmas.

Do you want to know when the subsolar point will be reached at your (tropical) location? You can find it on Time and Date:

- Search for your (tropical) location in the top search bar.

- Select 'Sun and moon'.

- Select 'See full month's sun'.

- Check the 'Solar noon' column. You're looking for the angle (shown in brackets) to be close to 90°.

Those outside of the tropics in southern Australia experience their shortest shadows during the summer solstice.

Comment. Tell us what you think of this article.

Share. Tell others.