Streaming Server-Side Rendering and Caching

Feb 07, 2018

2,322 views

This essay is archived

This essay might contain outdated information. I've preserved it for historical accuracy, but it might not be relevant anymore.

Originally published on the Zeit blog

React 16 introduced streaming server-side rendering, which allows you to send down HTML in chunks in parallel to rendering it. This enables a faster time to first byte and first meaningful paint for your users since the initial markup arrives in the browser sooner.

Streams are also asynchronous, contrary to renderToString, and handle backpressure well. This enables your Node.js server to render multiple requests at the same time and stay responsive in challenging conditions. It can pause React’s rendering if the network is saturated, and makes it so heavier requests doesn’t block lighter requests for a prolonged period of time. Since we were having some performance issues in our server-side rendering worker for Spectrum we recently implemented streaming, which turned out to have an interesting impact on our HTML caching.

Using renderToNodeStream

The API for streaming server-side rendering isn’t all that different from the standard renderToString API. Here’s what it looks like:

import { renderToNodeStream } from 'react-dom/server'

import Frontend from '../client'

app.use('*', (request, response) => {

// Send the start of your HTML to the browser

response.write('<html><head><title>Page</title></head><body><div id="root">')

// Render your frontend to a stream and pipe it to the response

const stream = renderToNodeStream(<Frontend />)

stream.pipe(response, { end: 'false' })

// When React finishes rendering send the rest of your HTML to the browser

stream.on('end', () => {

response.end('</div></body></html>')

})

})

An example of a streaming server-side rendering route When I first saw a similar piece of code in the React docs, it was pretty confusing because I’d never worked with Node.js streams before. Let’s dig into those for a second.

How Streams Work

renderToNodeStream returns a readable stream, which I imagine as a faucet: it has an underlying source of data (the tank holding the water) that’s waiting to be read by a consumer (waiting for the valve to be opened). To consume a readable stream (open the valve), we would listen to its “data” event, which is triggered whenever there is a new chunk of data to be read. In our case, the source is React rendering our frontend:

import { renderToNodeStream } from 'react-dom/server'

const stream = renderToNodeStream(<Frontend />)

stream.on('data', (data) => {

console.log(JSON.stringify(data))

})

Listening to a rendering stream’s data event

Not too complex, eh? Try running that in your app and you’ll see chunks of HTML being logged to the console one after the other. Looking at our rendering code above though, we’re obviously not listening to the data event manually. Instead, we’re piping the stream into the response object. What?!The response object in Node.js is a writable stream, which I imagine as a drain. When piped into each other, a readable stream essentially passes data in small chunks to the writable stream (imagine attaching a faucet directly to a drain, which itself connects to wherever you want the water to go). Writable streams can then do whatever they want with those chunks of data. In our case, we’re piping the React renderer (which outputs HTML) into the response writable stream, which will send the chunks to the requesting client in parallel to waiting for more:

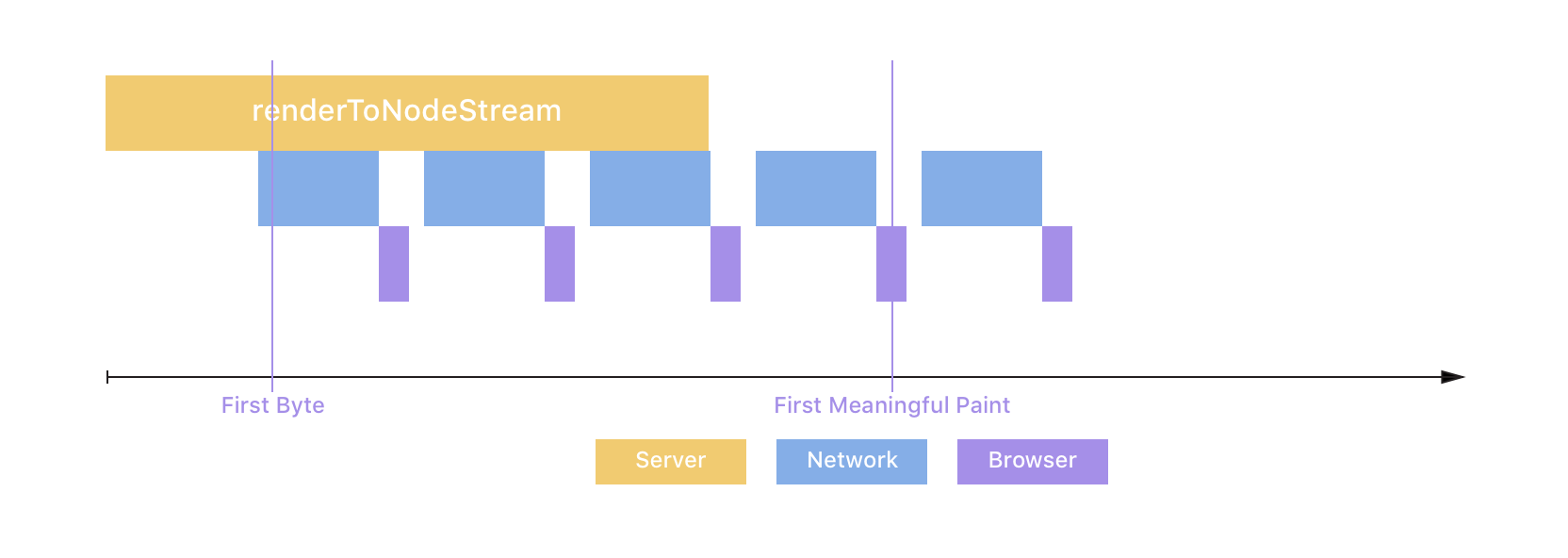

As you can see above, streaming decreases the Time-To-First-Byte, because the server sends the first bit of HTML sooner, and the Time-To-First-Meaningful-Paint, because the critical markup arrives at the browser earlier due to parallelization. Jackpot! 🏆

Caching HTML in Node.js

For Spectrum, we cache public pages in Redis to avoid React rendering them a million times over even though it’s always the same HTML in the end. We don’t cache anything for authenticated users because we install a ServiceWorker on first load, which serves an app shell locally on subsequent page visits, and this app shell fetches data from our API directly—no more server rendering! For public pages we previously monkey-patched response.send to cache them before responding to the user:

const originalSend = response.send

response.send = (html, ...other) => {

// Make sure not to cache (possibly temporary) error states

if (response.statusCode > 100 && response.statusCode < 300)

cache.put(request.path, html)

originalSend(html, ...other)

}

Monkey-patching response.send to cache the rendered HTML before returning it to the client Combined with a tiny Express middleware this allowed us to cache across many instances of our rendering worker:

app.use('*', (request, response, next) => {

if (cache.has(request.path)) {

// Return the HTML for this path from the cache if it exists

cache.get(request.path).then((html) => response.send(html))

} else {

// Otherwise go on and render it

next()

}

})

A tiny middleware for serving cached files

The million dollar question at this point is of course “How do you cache HTML when you’re streaming the response?“. Apart from the obvious issue that response.send isn’t called anymore you also never have access to the entire HTML document. By the time the renderer finishes rendering most of it will long have been sent to the user!

Caching Streamed HTML

Since I wasn’t very familiar with streams I turned to the Node.js community and asked them how to do this (shoutout to @mafintosh and @xander76 who patiently explained it all). It turns out there’s a third class of streams which allows us to cache the HTML: transform streams. Continuing the faucet analogy, a transform stream could, for example, be a water filter. You pass data (water) to the transform stream, which can transform it (clean it from gunk) before passing it on to the next stream. In our case, we don’t actually want to transform the data. Instead, we want to buffer all the HTML chunks of a single request in memory as they come along, then concatenate them together once we’re all done, and store the entire HTML document in the cache (imagine a water filter that duplicates each atom and stores it in a tank until all the water has flown). Here’s our tiny utility function for creating a caching transform stream:

import { Transform } from 'stream'

const createCacheStream = (key) => {

const bufferedChunks = []

return new Transform({

// transform() is called with each chunk of data

transform(data, enc, cb) {

// We store the chunk of data (which is a Buffer) in memory

bufferedChunks.push(data)

// Then pass the data unchanged onwards to the next stream

cb(null, data)

},

// flush() is called when everything is done

flush(cb) {

// We concatenate all the buffered chunks of HTML to get the full HTML

// then cache it at "key"

cache.set(key, Buffer.concat(bufferedChunks))

cb()

},

})

}

Usage: createCacheStream(request.path) to cache keyed by the request’s path

Now we can use that in our server-side rendering code:

app.use('*', (request, response) => {

// Create the cache stream and pipe it into the response

let cacheStream = createCacheStream(request.path)

cacheStream.pipe(response)

// Write the first bit of HTML into it

cacheStream.write(

'<html><head><title>Page</title></head><body><div id="root">'

)

// Create the rendering stream and pipe it into the cache stream

const renderStream = renderToNodeStream(<Frontend />)

renderStream.pipe(cacheStream, { end: false })

renderStream.on('end', () => {

// Once it's done rendering write the rest of the HTML

cacheStream.end('</div></body></html>')

})

})

An example of how to use the createCacheStream util to cache HTML

As you can see, we’re piping the rendering stream (faucet) into the cache stream (duplicating water filter) which passes the HTML on to the response (drain). Also note how we write the beginnging and the end of the HTML to the cacheStream instead of directly to the response to make sure our caching layer is aware of those bits of markup. That’s all there is to it, that’s how we cache the streamed HTML at Spectrum! As always, there’s things to improve in any code (this doesn’t handle cache stampedes, for example), but it’s serving us alright in production today.