Magnetic interactions of fundamental importance for iron-based high-temperature superconductors

(Phys.org)—For a long time, scientists and engineers have longed for a material that would conduct electricity at room temperature without any losses. More than 25 years ago scientists first discovered materials that were superconducting at relatively high temperatures: the cuprate-superconductors (copper-based superconductors). Iron-based high-temperature superconductors – a new class of materials discovered only a few years ago – also have this property. Together with Chinese and German collaborators, scientists at the Paul Scherrer Institute in Villigen (Switzerland) have now gained new insights into these superconductors. The experimental results indicate that magnetic interactions are of fundamental importance in the phenomenon of high-temperature superconductivity. This knowledge could contribute to the development of superconductors with improved technical properties in the future.

The results have been published in Nature Communications.

Conventional superconductors need extremely low temperatures. Then, these materials can conduct electricity without any resistance, which is something that enables technical applications utilizing particularly high magnetic fields such as particle accelerators or medical equipment. In the past two decades, particular research attention has been directed towards high-temperature superconductors. Such superconductors conduct electricity without losses even at higher temperatures. Because of this, scientists are constantly looking for new materials that are superconducting at temperatures as high as possible. In 2008, new high-temperature iron based superconductors were discovered. These superconductors are found mainly among iron-arsenide, iron-phosphor and iron-selenide alloys.

Very similar magnetic properties

Scientists at the Paul Scherrer Institute are at the cutting edge when it comes to research on iron-based superconductors. Their recent results, obtained using X-ray spectroscopy, have contributed to a better understanding of these materials. In their studies, they compared a sample of a superconducting material with a sample of the parent material, which is non-superconducting. The base material – in this case a barium-iron-arsenide compound – turns superconducting when a defined quantity of potassium atoms is introduced into it. By inserting these foreign atoms, the base material is doped with holes. Hole doping with potassium creates sites with a reduced number of electrons in the material, which affects the crystal structure and electrical conductivity.

The research team was particularly interested in the dynamic magnetic properties of the base materials and superconductors. In order to investigate these properties, they excited magnetic fluctuations in the material samples. Magnetic fluctuations (also known as spin waves or magnons) are accompanied by a reorientation of the neighbouring electron spins, which extends in a wavelike manner through the sample. In the base material, spin waves are clearly detectable. The researchers wanted to know if this was also true for the doped material samples. At first sight, one might suspect that holes introduced by hole doping, breaking the long range magnetic order of spins, would constitute obstacles and thus strongly attenuate the spin waves. However, the researchers found something different: the spin waves were hardly attenuated at all in the superconductor, and moreover, they had almost the same intensity as for the base material. "We have learned that magnetic fluctuations in superconducting materials occur at almost the same strength as in the base material. Hole doping with potassium caused hardly any significant disturbance to the spin waves", said PSI-researcher Dr. Thorsten Schmitt, summarising the results.

Approach for understanding high-temperature superconductivity

The dynamic magnetic properties of the base material and optimally doped superconductors were very similar in the case of iron-based high-temperature superconductors. "Our interpretation of this intriguing fact is that the magnetic interaction may be involved in the transition to the superconducting phase. We are currently improving our technique even further, to be able to demonstrate even minute changes in magnetic properties that may arise during this transition to the superconducting phase", said Schmitt.

With their work, Schmitt and his research colleagues make important contributions to our understanding of high-temperature superconductivity. It is generally accepted that superconductivity arises through two electrons 'glued' together to form a so called "Cooper Pair". In a high temperature superconductor, magnetic interactions could potentially be responsible for binding the electron pairs. "Spin waves are the hottest candidates for this", said Thorsten Schmitt.

Investigations with X-ray light

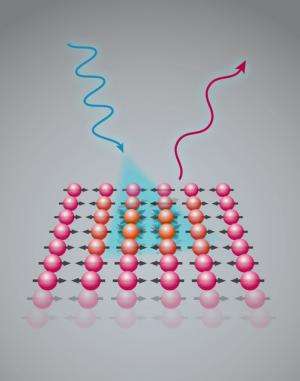

For their studies, the researchers used the ADRESS-beamline at the Swiss Light Source SLS, a large research installation at the Paul Scherrer Institute, which provides X-rays of very high intensity for scientific experiments. In the experiment, the dynamic magnetic properties of the base material and the superconductor were examined using Resonant Inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS). In this spectroscopic method, the material being investigated is irradiated with X-rays. The X-rays excite a spin wave in the sample – and thereby lose energy. "By comparing the energies of the incident and the outgoing light, one can deduce information on the properties of the spin waves", said Kejin Zhou, who conducted these measurements as part of his Post-Doctoral activities at PSI.

PSI-researchers want to deepen their understanding of high-temperature superconductors even further. This will include conducting experiments for different degrees of doping around the value at which superconductivity sets in. Studies on other classes of iron-based superconductors are also planned.

More information: Zhou, K. et al. Persistent high-energy spin excitations in iron pnictide superconductors, Nature Communications 12 February 2013 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms2428

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by Paul Scherrer Institute