Abstract

Axons of cerebellar molecular layer interneurones (MLIs) bear ionotropic glutamate receptors. Here, we show that these receptors elicit cytosolic [Ca2+] transients in axonal varicosities following glutamate spillover induced by stimulation of parallel fibres (PFs). A spatial profile analysis indicates that these transients occur at the same locations when induced by PF stimulation or trains of action potentials. They are not affected by the NMDAR antagonist AP-V, but are abolished by the AMPAR inhibitor GYKI-53655. Mimicking glutamate spillover by a puff of AMPA triggers axonal [Ca2+]i transients even in the presence of TTX. Addition of specific voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel (VDCC) blockers such as ω-AGAIVA and ω-conotoxin GVIA or broad range inhibitors such as Cd2+ did not significantly inhibit the signal indicating the involvement of Ca2+-permeable AMPARs. This hypothesis is further supported by the finding that the subunit specific AMPAR antagonist IEM-1460 blocks 75% of the signal. Bath application of AMPA increases the frequency and mean peak amplitude of GABAergic mIPSCs, an effect that is blocked by philanthotoxin-433 (PhTx) and reinforced by facilitating concentrations of ryanodine. By contrast, a high concentration of ryanodine or dantrolene reduced the effects of AMPA on mIPSCs. Single-cell RT-PCR experiments show that all GluR1–4 subunits are potentially expressed in MLI. Taken together, the results suggest that Ca2+-permeable AMPARs are colocalized with VDCCs in axonal varicosities and can be activated by glutamate spillover through PF stimulation. The AMPAR-mediated Ca2+ signal is amplified by Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, leading to GABA release by MLIs.

Recent studies have demonstrated the importance of presynaptic ionotropic glutamate receptors in modulating neurotransmitter release (reviewed in Engelman & MacDermott, 2004; Schenk & Matteoli, 2004; Rusakov, 2006). In the cerebellum, molecular layer interneurones (MLIs) possess a variety of glutamate receptors, including mGluRs (Baude et al. 1993; Karakossian & Otis, 2004), AMPARs (Barbour et al. 1994), NMDARs (Monyer et al. 1994) and KARs (Bahn et al. 1994). Exogenous activation of either AMPARs or NMDARs increases the frequency of IPSCs in MLIs in the absence of presynaptic action potential firing (Bureau & Mulle, 1998; Glitsch & Marty, 1999). Moreover, activation of presynaptic NMDARs promotes the spontaneous release of Ca2+ from presynaptic ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ stores (RyCSs) thus enhancing the release of GABA at the MLI-Purkinje cell synapse (Duguid & Smart, 2004) and activation of extrasynaptic NMDARs induces a switch in synaptic receptor subtypes under PKC control (Sun & Liu, 2007). Finally, it has been demonstrated in cerebellar cultures that AMPARs are present in developing GABAergic terminals and their activation affects the size of GABAergic terminals and spontaneous GABA release (Fiszman et al. 2007).

Activation of presynaptic receptors is often ascribed to spillover of neurotransmitter. Several lines of evidence indicate that stimulation of parallel fibres (PFs) can lead to substantial build-up of glutamate concentration in the molecular layer and to consequent activation of ionotropic glutamate receptors. Carter & Regehr (2000) examined the activation of ionotropic glutamate receptors at the PF to stellate cell synapse as a function of presynaptic stimulation patterns. Stimulus trains, but not single stimuli, generate a prolonged EPSC mediated mostly by activation of AMPARs, reflecting glutamate spillover. Recent evidence indicates that spilled-over glutamate released from PFs can activate NMDARs located in axons of stellate cells inducing a long-lasting enhancement of GABA release (Liu & Lachamp, 2006). Liu (2007) found that PF stimulation activates axonal AMPARs and transiently suppresses autoreceptor and autaptic GABAergic currents in stellate cells. On the other hand, the Konishi laboratory has shown that glutamate released from climbing fibres (CFs), but not from PFs, activates presynaptic AMPARs suppressing evoked GABA release from basket cells onto Purkinje cells. This input-specific modulation has been attributed to the close proximity of CFs to the axons of the basket cells (Satake et al. 2000).

In light of these data, it appears of primary importance to elucidate the specific location and the subunit composition of axonal AMPARs, as well as the signalling pathways that they activate. The subunits forming AMPARs (GluR1–4) assemble as homo- or heterotetramers, the functional properties of which are dictated by their subunit composition. Tetramers that lack the GluR2 subunit are permeable to Ca2+ ions (Cull-Candy et al. 2006; Isaac et al. 2007) and are likely to activate specific Ca2+-dependent signalling pathways.

In this work, we study the axonal [Ca2+]i rise induced by AMPA puffs or by brief stimulus trains applied to PFs. Using pharmacological and molecular tools, we find that Ca2+-permeable AMPARs are located at the same hot spots where action potentials evoke [Ca2+]i transients, and that these receptors are activated by glutamate spillover. Furthermore, we demonstrate that AMPA increases synaptic activity at MLI–MLI synapses in a PhTx-dependent manner, an effect that is amplified by RyCSs mobilization. By contrast, AMPA effects at MLI–Purkinje cell synapses are not sensitive to PhTx. Altogether, our results demonstrate the presence of Ca2+-permeable AMPARs in MLI–MLI terminals and indicate that MLI axons are able to express different subtypes of AMPARs depending on the type of postsynaptic cell they contact.

Methods

Slice preparation

Sprague–Dawley rats 2–21 days old were anaesthetized with halothane and decapitated, as approved by the University Paris V Institutional Animal Care Committee. Parasagittal (180 μm) or coronal/transverse (180 μm) cerebellar slices were cut with a vibroslicer (Leica VT 1200S, Leica Microsystems, France) in ice-cold bicarbonate buffered saline (BBS) solution containing the following (in mm): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26.2 NaHCO3 and 10 glucose (saturated with 95% O2–5% CO2), pH 7.3. The slices were incubated at ∼34°C for 30 min and were then stored at room temperature. During recordings, the slices were superfused with the above solution (1–1.5 ml min−1) at room temperature (20–23°C) or at near physiological temperature (35°C) when indicated.

Stellate and basket cells

In the present report, the same results were found in all interneurones tested irrespective of their location in the molecular layer, and we therefore refer collectively to stellate and basket cells as MLIs.

Recording and analysis of IPSCs

MLIs were maintained under voltage clamp in the whole-cell recording (WCR) configuration at a holding potential of −70 mV. The intracellular solution contained (in mm): 150 KCl, 4.6 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 10 Hepes-K, 1 mm EGTA-K, 0.4 Na-GTP and 4 Na-ATP, pH 7.3. Tight-seal WCRs were obtained with borosilicate pipettes (4–6 MΩ) from superficial somata using an EPC-9 amplifier (HEKA Electronik, Darmstadt, Germany). Series resistance values ranged from 15 to 25 MΩ and were compensated for by 60%. Currents were filtered at 1.3 kHz and sampled at a rate of 250 μs per point. α-Amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoazol-4-propionate (AMPA) was eventually added to the bath at 0.5–1 μm. Detection and analysis of IPSCs were performed off-line with routines written in the IGOR Pro programming environment (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, USA). Note that in MLIs, most spontaneous synaptic currents were blocked by bicuculline (20–50 μm) and were therefore mediated by activation of GABAA receptors. IPSCs and EPSCs could be distinguished based on the decay kinetics of the two currents as reported (Llano & Gerschenfeld, 1993).

Calcium imaging

Interneurones in the molecular layer were identified using an upright microscope (Axioscop, Zeiss, Germany) with Nomarski differential interference contrast (DIC) optics, a 60× Olympus objective, 0.90 NA water immersion objective, and a 0.63 NA condenser. WCR pipettes were filled with (in mm): 140 potassium gluconate (or caesium gluconate when indicated), 5.4 KCl, 4.1 MgCl2, 9.9 Hepes-K, 0.36 Na-GTP, 4 Na-ATP and 0.1 Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1 (Molecular Probes Europe, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Digital fluorescence images were obtained using an excitation-acquisition system from T.I.L.L. Photonics (Gräfelfing, Germany). Briefly, to excite fluorescence of the Ca2+ dye OG1, light from a 75 W Xe lamp was focused on a scanning monochromator set at 488 nm and coupled, by a quartz fibre and a lens, to the microscope, equipped with a dichroic mirror and a high-pass emission filter centred at 505 and 507 nm, respectively. Images were acquired by a Peltier-cooled CCD camera (IMAGO QE; 1376 × 1040 pixels; pixel size: 244 nm after 53× magnification and 2 × 2 binning). To induce axonal [Ca2+]i rises, trains of APs (two or four APs at 20 ms intervals) were produced by depolarizing the cell for 3 ms to 0 mV from a holding value of −70 mV which induces a propagated action potential (Tan & Llano, 1999). Extracellular stimulation of PFs was performed by applying voltage pulses (100–200 μs duration; 6–60 V amplitude) between a reference platinum electrode in the bath and another platinum wire in a pipette filled with a solution containing (in mm): 145 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2 and 10 Hepes-Na (input resistance, 2–3 MΩ). This pipette was displaced in the molecular layer until a stable synaptic response was evoked. For focal application of AMPA, a patch pipette filled with a solution containing AMPA was coupled to a Picospritzer II (Intracel, UK) system. It was placed above the slice surface, at roughly 40 μm from the recorded MLI cell body. Analysis was performed by calculating the average fluorescence in regions of interest (ROIs) as a function of time as detailed before (Collin et al. 2005). Additional experiments (see text) were performed on a home-made two-photon fast laser-scanning system based on the design of Tan & Llano, 1999), with some modifications. Briefly, two-photon excitation was performed with a MaiTai Ti-Sapphire laser (Spectra-Physics France) set at an excitation wavelength of 820 nm; the average power at the specimen plane was kept below 10 mW. Axonal subregions were scanned by displacing the laser beam in the x–y direction with two galvanometers, using scanning and signal acquisition procedures as previously described (Tan et al. 1999). The effective pixel size was set at 250 nm. The emitted light was focused on the active surface of a photon-counting avalanche photodiode (SPCM-AQR-13; PerkinElmer Optoelectronics, Fremont, CA, USA) and sampled at 10 μs point−1 as detailed by Tan et al. (1999). For most experiments, images were acquired with a dwell time of 50–100 ms per image.

During recording, the BBS was sometimes supplemented with 1-(4-aminophenyl)-3-methylcarbamyl-4-methyl-3,4-dihydro-7,8-(methylenedioxy)-5H-2,3-benzodiazepine (GYKI 53655); 1-trimethylammonio-5-(1-adamantane-methylammoniopentane) dibromide (IEM 1460); dl-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP-V); bicuculline or cyclothiazide (CTZ). All these chemicals were purchased at Tocris (Bristol, UK) except GYKI 53655, a kind gift of Dr M. Spedding (Servier, France). Other chemicals were purchased from Sigma.

Single-cell reverse transcription-PCR

We studied the expression patterns of four genes encoding AMPA receptor subunits GluR1–4 by single-cell reverse transcription (RT)-multiplex PCR (RT-mPCR) (Christophe et al. 2005). All MLIs used for this analysis were recorded in acute slices. At the end of the experiment, the content of the cell was aspirated under visual control into the recording pipette. This operation was halted either before or as soon as the seal was lost. Patch pipettes were filled with 10 μl of a sterile-filtered and autoclaved solution containing the following (in mm): 140 KCl, 5 Hepes, 3 MgCl2 and 5 EGTA, pH 7.3. The content of the pipette was expelled into a sterile 0.2 ml test tube for reverse transcription reactions by breaking the very tip of the pipette into the tube and simultaneously applying positive pressure to the pipette. The usual volume recovered was ∼5 μl. To perform the one-step RT-PCR, this volume was brought to 50 μl with the following components at final concentrations, as follows: 0.5 μm forward primers, 0.5 μm reverse primers, 25 μl of 2× buffer of the SuperScript III One-Step RT-PCR System (containing 0.2 mm each of the four deoxyribonucleotide trisphosphate and 1.2 mm MgCl2 final concentration; Invitrogen) and 2 μl of the enzyme mixture (Superscript III RNaseH– reverse transcriptase and Platinum Taq Polymerase). The resulting 50 μl mix was incubated for 45 min at 55°C and then submitted to 40 PCR cycles (15 s at 94°C, 30 s at 56°C, 60 s at 68°C) with an initial denaturation period of 2 min at 94°C and a final elongation of 5 min at 68°C. The PCR products were re-amplified in simplex mode with a unique pair of primers. The reaction was set up as follows: 2 μl of 10× reaction buffer (yielding to 1.5 mm MgCl2 final concentration; Qiagen), 0.5 μm forward primers, 0.5 μm reverse primers, 0.2 mm each of the four deoxyribonucleotide trisphosphate, 2.5 U of Taq Polymerase and water up to 20 μl. Thirty PCR cycles (45 s at 94°C, 60 s at 56°C, 60 s at 72°C) were then performed with an initial denaturation period of 3 min at 94°C and a final elongation of 10 min at 72°C. The primers used have the following sequence and are listed in the forward and reverse order: GluR1: 5′-TTACCACAGAGGAAGG-CATGATC-3′ and 5′-CAGTCC CAGCCCACCAATC-3′; GluR2: 5′-TGTGTTTGTGAGGACTACCGCA-3′ and 5′-GGATTCTTTGCCACCTTCATTC-3′; GluR3: 5′-GCAGAGCCATCTGTGTTTACCA-3′ and 5′-AGTTTTGGGTGTTCTTTGTGAGTT-3′; GluR4: 5′-GCAGAGCCGTCTGTGTTCACTAG-3′ and 5′-TTTCTTTCTTGTGGCTTCGGA-3′.

The result of the PCR for each tested gene in all experiments was taken into account when the positive control reaction demonstrated a single major band of correct size, whereas the negative control reaction (without reverse transcriptase) generated no detectable products other than primer dimers. As a control, harvesting pipettes were briefly brushed on the slice surface, and the amplification procedure was repeated as for whole-cell recordings. All of the PCR fragments amplified from mRNA spanned at least one intron to prevent or at least identify amplification of genomic DNA.

Statistical analysis

The coefficient of variation (CV) of the IPSC amplitude was calculated as the ratio between the s.d. and the mean amplitude evaluated for groups of 20 consecutive sweeps. Data were considered significantly different when P < 0.05 and indicate by a star (*) on the figures. Mean values are given with s.e.m.

Results

PF stimulation triggers [Ca2+]i transients in MLIs axons

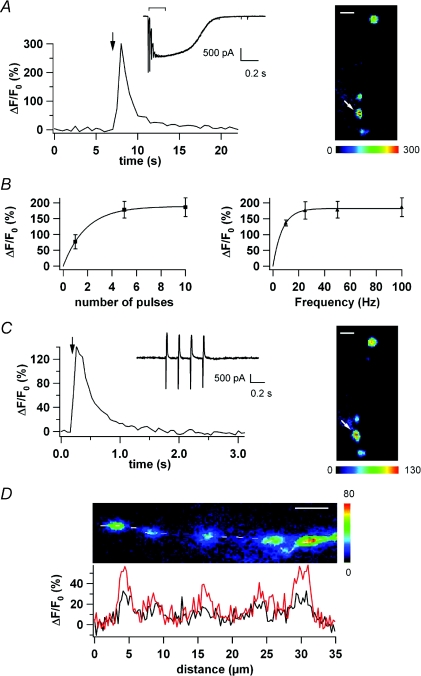

Brief stimulus trains of 10 pulses at 50 Hz in the molecular layer induced [Ca2+]i transients that were heterogeneously distributed along MLI axons (Fig. 1A; ΔF/F0 image in the right panel), with the largest and fastest responses appearing in hot spots on average ∼5 μm apart. Simultaneously, the train stimulation of PFs generates a complex synaptic response (Fig. 1A, inset). The peak EPSCs of this response increased during the train, reflecting an augmentation in the probability of release caused by facilitation as reported (Atluri & Regehr, 1998; Carter & Regehr, 2000). Moreover, this EPSC had a prolonged component that has been attributed to NMDA and AMPA receptor activation by glutamate spillover (Carter & Regehr, 2000). After a PF train (10 pulses at 50 Hz), ΔF/F0 increases of 168 ± 30% (n= 8) were measured in axonal hot spots, corresponding approximately to a 2.5-fold [Ca2+]i rise. The fluorescence signals decayed back to baseline within a few seconds (Fig. 1A). These [Ca2+]i transients are likely to result from glutamate spillover reaching the axons and activating clusters of ionotropic receptors. Nevertheless, one could propose an indirect effect via activation of somatodendritic AMPARs since recent work has revealed extensive electrical coupling between soma and axon in MLIs (Mejia-Gervacio et al. 2007). This seems rather unlikely here because the soma was voltage clamped and depolarization through recording pipette Rs is less than that necessary to activate Na+ channels. We nevertheless verified the contribution of TTX-sensitive Na+ channels to the PF-induced [Ca2+]i transients by using an internal solution containing the lidocaine derivative QX-314. MLIs were dialysed with the same internal solution as above complemented with QX-314 (6 mm, final concentration). After a PF train (10 pulses at 50 Hz), ΔF/F0 increases of 75 ± 9% (n= 9; not illustrated) were measured in axonal hot spots indicating that the response does not rely on TTX-sensitive Na+ channels. In these experiments, however, the increase in ΔF/F0 was smaller than in control conditions (P < 0.02, Student's t test). This is likely to result from the fact that in the presence of QX-314, the standard procedure to identify hot spots (i.e. maximal [Ca2+]i in response to propagated APs) could not be followed. Thus, we had to rely exclusively on visual criteria and our data contain a mixture of hot spots and less responsive regions. Increasing the number of PF stimulations and/or their frequency results in an infra-linear increase of the peak ΔF/F0 value as illustrated (Fig. 1B). Such variation in the signal amplitude parallels that of the PF-evoked EPSC that plateaus when the number of pulses is increased from 1 to 5 or when the frequency of a five pulse train is increased from 10 to 100 Hz (Carter & Regehr, 2000). Figure 1C shows an AP-evoked [Ca2+]i transient occurring in the same axonal location where the PF-evoked fluorescence changes had been recorded (APs were induced by somatic depolarization, see Methods). To assess the respective location of PF- and AP-driven [Ca2+]i signals, we compared the distribution of the respective fluorescence levels along a line drawn on the axon (Fig. 1D). This mode of analysis allows characterization of the spatio-temporal profile of Ca2+-dependent fluorescence changes and therefore provision of information about the axonal localization of the molecules responsible for the transients (Forti et al. 2000). Figure 1D shows that the AP-evoked [Ca2+]i transients occur exactly at the same locations as the PF-evoked signals (n= 5). Finally, it is known that performing experiments at room temperature will result in more prolonged glutamate transients as glutamate uptake by transporters is highly temperature dependent. Thus, our central findings needed to be confirmed at near-physiological temperature. Carter & Regehr (2000) showed that the glutamate spillover obtained by PF stimulation is still present at physiological temperature. Moreover, Liu (2007) shows that at 34°C, spillover is able to activate presynaptic glutamate receptors in MLIs. In line with these earlier publications, we found that stimulating PFs at 35°C gave rise to ΔF/F0 increases of 117 ± 38% (n= 3) in axonal hot spots, indicating that the phenomenon we observe happens at near physiological temperature.

Figure 1. Stimulation of PFs evokes intracellular [Ca2+]i transients in MLI axons.

A, left panel, time course of ΔF/F0 in an axonal hot spot following PF stimulation (arrow; 10 pulses, 50 Hz); simultaneous current recording (inset; stimulation duration indicated by the bar above the current trace). Note the glutamate spillover recognizable by the slow current component. Right panel, ΔF/F0 image at the peak of the response; the analysed region (hot spot) is indicated by a white arrow. B, left panel, averaged peak ΔF/F0 is plotted versus number of PF stimulations (N= 3 cells; multiple stimulations have been performed at a frequency of 50 Hz). Right panel, peak ΔF/F0 is plotted versus the frequency for 5 PF stimulations (N= 3 cells). C, left panel, time course of ΔF/F0 evoked by a 4AP train in the same hot spot as in A; simultaneous current recording (inset). Right panel, ΔF/F0 image at the peak of the response; the analysed region (hot spot) is indicated by a white arrow. D, ΔF/F0 image of the same axon as in A (90 deg inclination, top image). A dotted line running along the axon is superimposed. ΔF/F0 analysis was performed along the dotted line (see Methods). ΔF/F0 values corresponding to a 4-AP train (black trace) or PF stimulation (red trace) are plotted versus axonal distance (bottom graph). All pseudocolour calibration bars in this and in the following figures indicate ΔF/F0 as a percentage. Space calibration bar for the images in A, C and D: 5 μm.

Presynaptic AMPARs are activated by PF stimulation

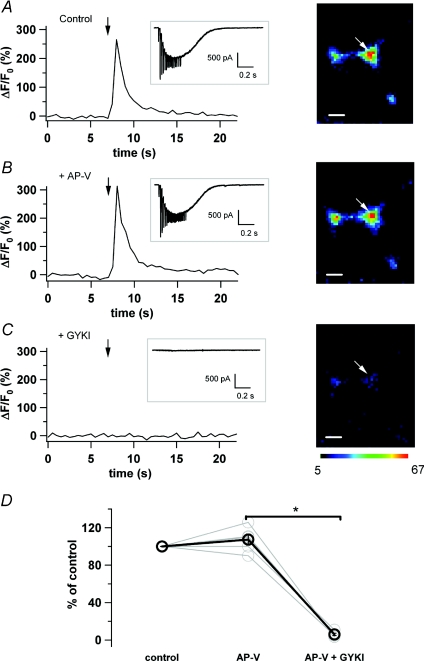

Figure 2A and B shows that both the current and [Ca2+]i signal elicited by PF stimulation are unaffected by the NMDAR antagonist AP-V (50 μm, ΔF/F0= 107.29 ± 5.92% of control; n= 5; P > 0.05, Student's paired t test). In contrast, fluorescence and current responses to PF stimulations totally disappeared after bath perfusion of the specific blocker of AMPARs GYKI 53655 (40 μm, ΔF/F0= 6.03 ± 1.26% of control, n= 5; P < 0.05, paired t test; Fig. 2C). The pharmacological results summarized in Fig. 2D indicate that NMDARs are not involved in the axonal [Ca2+]i response to glutamate spillover in our conditions and that the [Ca2+]i transients recorded in response to PF stimulation rely on AMPAR activation. These results are in keeping with Carter & Regehr (2000) who established that although glutamate spillover can activate both NMDARs and AMPARs at the PF-MLI synapse, the NMDA component is minor at a holding potential of −70 mV and in the presence of external Mg2+. In this context, activation of AMPARs by spilled-over glutamate could depolarize the terminal leading to a VDCC-driven Ca2+ increase at the hot spot. An alternative explanation is that Ca2+ could directly enter through AMPAR-associated channels if these channels are Ca2+ permeable.

Figure 2. AMPARs mediate the axonal [Ca2+]i transients evoked by PF stimulation.

A, left panel, ΔF/F0 time course in a MLI axon and corresponding current recording (inset) during PF stimulation (10 pulses, 100 Hz at the time indicated by the arrow). Right panel, ΔF/F0 image at the peak of the response of the recorded axon (hot spot of interest indicated by the white arrow). B, same as in A in the presence of the specific NMDAR antagonist AP-V (50 μm). C, same as A in the presence of AP-V (50 μm) and of the specific GluR2-lacking AMPAR antagonist GYKI 53655 (40 μm). D, summary plot of pooled data. Space calibration bar for the images in A, B and C: 2 μm.

Axons contain Ca2+ permeable AMPARs

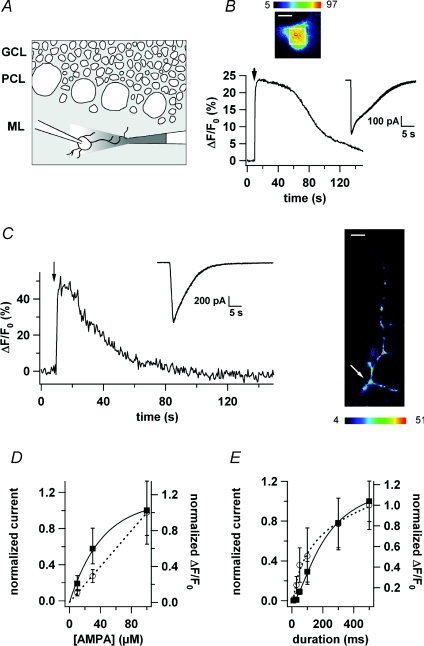

The question arises as to whether presynaptic AMPARs are permeable to Ca2+ ions or whether their activation just leads to depolarization in the axon thereby opening VDCCs in hot spots. To address this question, we set up a protocol to simulate glutamate spillover by a puff of AMPA on voltage-clamped interneurones (Fig. 3A). Figure 3B illustrates the current trace as well as the [Ca2+]i transient elicited by a puff of AMPA (100 μm; 500 ms) in the soma of a stellate cell bathed in normal BBS. Note that puffing AMPA onto the MLI gives rise to a significant somatic Ca2+ signal (ΔF/F0= 33 ± 7%, n= 5) which was about half of the somatic signal obtained with PF stimulation (10 pulses at 50 Hz; ΔF/F0= 65 ± 11%, n= 6; not illustrated). MLI axons were also examined during AMPA puffs. Figure 3C (right panel) shows a ΔF/F0 image of a MLI axon at the peak response to a puff of AMPA. As in PF stimulation experiments, the [Ca2+]i rise was restricted to hot spots. The results illustrated in Fig. 3D and E show that both the current amplitude and the ΔF/F0 recorded in the axonal hot spots increased with puff duration and with AMPA concentration. In view of these data, we chose to perform the pharmacological experiments below with a puff length of 500 ms and an AMPA concentration of 100 μm.

Figure 3. A puff of AMPA mimicks glutamate spillover.

A, illustration of the AMPA puff protocol. GCL: granular cell layer; PCL: Purkinje cell layer; ML: molecular layer. B, upper panel, ΔF/F0 image of a MLI soma at the peak of the response to a puff of AMPA (100 μm, 500 ms). Lower panel, time course of ΔF/F0 for the somatic region of interest delimited by the white square on the upper panel and simultaneous current recording (inset). C, left panel, time course of ΔF/F0 for an axonal hot spot and simultaneous current recording (inset) during an AMPA puff. Right panel, ΔF/F0 image of the axon at the peak of the response to the puff. The hot spot analysed is indicated by the white arrow. Same cell as in B. D, normalized current peak amplitude and peak ΔF/F0 increase as a function of AMPA concentration (▪: current; ◯: ΔF/F0; n= 3). E, normalized current peak amplitude and peak ΔF/F0 increase as a function of puff duration (▪: current; ◯: ΔF/F0; n= 3). Space calibration bar for the images in B and C: 5 μm.

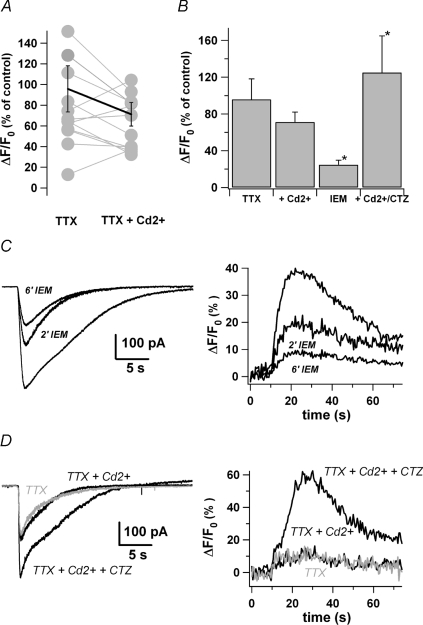

To further characterize the axonal AMPA response, we added TTX (0.5 μm) to the bath before applying the agonist. Under these conditions, the [Ca2+]i signal was not significantly different from the control in the hot spots (96 ± 22% of control, n= 15; P > 0.05, paired t test; Fig. 4B) indicating that the signal did not depend on APs. The next question is whether a fraction of the axonal AMPARs are Ca2+ permeable. When Cd2+ (50 μm, final concentration), a well known VDCC blocker, was added to the perfusate in the presence of TTX, the signal was not significantly modified (71 ± 11%versus 96 ± 22% of control, n= 15; P > 0.3, paired t test; Fig. 4A and B) and the [Ca2+]i rises were still restricted to hot spots (n= 15). These results indicate that MLI axons contain Ca2+-permeable AMPARs colocalized with the VDCCs in the varicosities. The concentration of Cd2+ used in this study is clearly sufficient to block axonal VDCCs since 10 μm achieved a 50−80% reduction of AP-evoked [Ca2+]i transients (Forti et al. 2000) and nearly totally blocked the whole cell current elicited by a depolarization from −70 to 0 mV (n= 4; see online supplemental material, Supplementary Fig. 1B). To confirm these results, we performed additional experiments with a cocktail of toxins (ω-agatoxin IVA +ω-conotoxin GVIA) directed against the VDCCs identified in axonal varicosities by Forti et al. (2000). These experiments were done with a Cs+-based internal solution to measure the contribution of Ca2+ entry through Ca2+-permeable AMPARs in varicosities with sufficient accuracy. However, the kinetic of action of the toxins is relatively slow (around 10 min) in slices and concentrations as high as 500 nm are required. Such kinetics lead to long lasting experiments that may be biased by photodamage if carried out on a classical CCD-based imaging set-up. We therefore chose to perform the experiments on a two photon set-up as mentioned in Methods. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 2, 79 ± 15% (n= 3) of the signal triggered by a puff of AMPA was maintained after a 10 min perfusion of a mixture containing 200 nmω-agatoxin IVA and 500 nmω-conotoxin GVIA for 10 min. Since Ca2+ permeable AMPARs lack the GluR2 subunit, the results indicate that GluR2-lacking AMPARs are present in the axons and mediate the Cd2+-resistant Ca2+ entry. Extracellularly applied dicationic adamantine derivatives selectively block inward currents through GluR2-lacking AMPAR channels (Herlitze et al. 1993; Magazanik et al. 1997; Washburn et al. 1997; Tikhonov et al. 2000). We checked the axonal AMPAR sensitivity to IEM-1460, which selectively blocks GluR2-lacking receptors in a use-dependent manner (Magazanik et al. 1997). Figure 4C shows that both the AMPAR-mediated current and the associated Ca2+ signal were progressively inhibited by application of 40 μm IEM-1460 (after 6 min, peak current: 35 ± 3% of control and peak ΔF/F0: 24 ± 4% of control, n= 4, Fig. 4C). When cyclothiazide (CTZ; 40 μm), which reduces AMPAR desensitization (Partin et al. 1993; Yamada & Tang, 1993), and increases the apparent affinity of AMPARs for glutamate (Trussell et al. 1993; Partin et al. 1996) was added to the superfusate in the presence of TTX and Cd2+, the Ca2+ response reached 125 ± 40% of control (n= 7; summary in Fig. 4B). Since the response amplitude under TTX/Cd2+ conditions was only 71% of control (see above), the CTZ-driven increase was of about a factor of 2 (125 versus 71% of control). At the current level, however, the increase was smaller since the peak amplitude reached 140 ± 34% of control (n= 7; Fig. 4D). Since CTZ is known to reduce AMPARs desensitization, it seems warranted to analyse the currents in terms of integral versus time (∫Idt). In this case, the calculated area displayed a 2.7-fold increase in the presence of CTZ versus Cd2+ (271 ± 64% of control, n= 5) thus reducing the difference between current and Ca2+ data. CTZ effects are known to depend on the subunit isoforms involved in AMPAR formation. The effects of CTZ are more pronounced at synapses that have rapidly desensitizing AMPA receptors like GluR2-lacking receptors. For instance in MLIs, Liu & Cull-Candy (2002) demonstrated that CTZ induces a large increase in the amplitude of synaptic currents mediated by a mixed receptor population and little change in the current mediated by GluR2-containing receptors. In conclusion, the pharmacological properties of the axonal AMPAR-mediated Ca2+ signals suggest that axonal AMPARs lack the GluR2 subunit.

Figure 4. Presynaptic AMPARs are calcium permeable and colocalize with VDCC in defined hot spots.

A, peak ΔF/F0 of hot spots in MLI axons during puffs of AMPA (100 μm, 500 ms; n= 15) recorded in TTX (500 nm). Pairs of circles joined by a line represent one cell. B, summary plot of the relative peak ΔF/F0 of the hot spots during a puff of AMPA in different conditions (500 nm TTX, n= 15; 500 nm TTX + 50 μm Cd2+, n= 15; 500 nm TTX + 50 μm Cd2++ 40 μm CTZ, n= 7; 500 nm TTX + 40 μm IEM 1460, n= 4). C, left panel, typical current recording of a MLI during a puff of AMPA in control condition, after 2 min and 6 min of bath applied IEM 1460. Right panel, corresponding ΔF/F0 time courses (averages of 2 or 3 trials). D, left panel, typical current recording of a MLI during a puff of AMPA in the presence of 500 nm TTX, after addition of 50 μm Cd2+ and CTZ (50 μm). Right panel, corresponding ΔF/F0 time courses.

We have also performed the puff experiments at 35°C to verify the functionality of the Ca2+-permeable AMPARs at near-physiological temperature. Under these conditions, 66 ± 18% (n= 6) of the puff-evoked Ca2+ rise remained when Cd2+ (50 μm) was added to the TTX-containing superfusate (not illustrated). These results are similar to those obtained at room temperature.

Bureau & Mulle (1998) reported that low concentrations of domoate failed to enhance the frequency of mIPSCs of MLIs recorded on mature animals indicating that the modulation of mIPSCs by AMPA decreases with age. These authors discussed the possibility that the developmental switch could be due to a displacement of AMPARs from the axonal to the somato-dendritic compartment. To resolve this issue, we performed the same Ca2+ imaging experiments with older animals (PN 19–21). Under these conditions, when Cd2+ (50 μm) was added to the TTX-containing extracellular solution, only 34 ± 9% (n= 5; not illustrated) of the AMPA puff-evoked Ca2+ response remained whereas more than 67% of the response was still present with the same protocol and PN 12–15 animals. This clearly indicates that the Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptor tends to disappear from the axon when the animals get older. It seems likely that the activation of Ca2+-permeable AMPARs represents a developmental state that does not persist in mature neurons.

AMPAR activation leads to an increase in the frequency of mIPSCs in MLIs

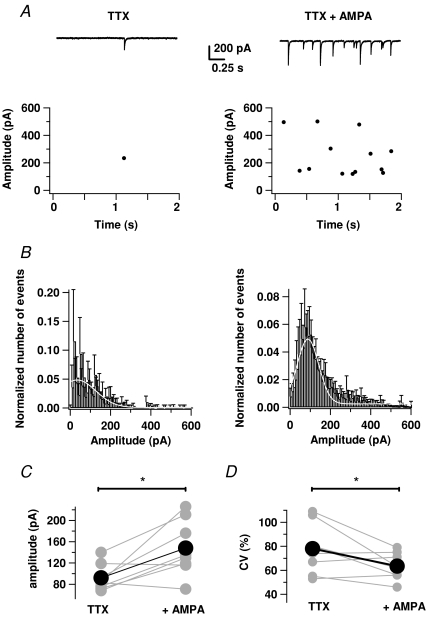

In the presence of TTX (0.5–1 μm) IPSCs displayed a frequency of 0.38 ± 0.08 Hz (n= 12; Fig. 5A) and an amplitude of 99.76 ± 11.23 pA (n= 12). Application of AMPA at low concentrations (0.5–1 μm) in the presence of TTX caused a sharp increase in the frequency of miniature GABAergic synaptic currents in MLIs (8.00 ± 2.26 versus 0.38 ± 0.08 Hz, n= 12; P < 0.01, paired t test; Fig. 5A and B). Note that the peak inward current was always under −100 pA in these experiments (−74 ± 12 pA, n= 16). On average, AMPA led to a 24-fold increase in mIPSC frequency (n= 12). These results extend those obtained with mice by using either AMPA or domoate, a low affinity agonist of KA and AMPA receptors (Bureau & Mulle, 1998). Figure 5B depicts the average amplitude distributions of mIPSCs in TTX and TTX + AMPA conditions. In TTX, the distribution was highly skewed toward large values and had a high average CV (78 ± 7%, n= 8) as previously reported (Auger & Marty, 1997). In the presence of AMPA, however, the distribution was closer to a normal profile and the CV was smaller (64 ± 4 versus 78 ± 7%, n= 8; P < 0.05, paired t test). In addition, AMPA generated a significant increase in mIPSC amplitude (148 ± 19 versus 92 ± 9 pA in TTX; n= 8; P < 0.02, paired t test; Fig. 5C). Figure 5D shows the individual changes in the CV for the eight cells averaged in the histograms. The presence of AMPA in the bath clearly induces a diminution of the CV. Altogether, these data reveal a potent and complex presynaptic modulation of synaptic transmission by AMPAR activation in the absence of action potential firing.

Figure 5. AMPA increases the frequency and mean peak amplitude of GABAergic mIPSCs.

A, upper panels, samples of a continuous current recording of mPSCs in a MLI before (left trace) and during (right trace) the application of AMPA (0.5 μm). Lower panels, plots for the same cell of the amplitude of GABAergic mIPSCs before (left graph) and after (right graph) the application of AMPA. The points joined by a black line (panel C) correspond to the mean ±s.e.m. for this dataset. B, histograms of GABAergic mIPSC peak amplitudes in control (left) and in the presence of AMPA (right) averaged from 8 cells. The white curves corresponds to the best approximation of the data by a Gaussian function. C, mean amplitude values are shown for n= 8 cells in both conditions. D, CV for mIPSC amplitude values are shown for n= 8 cells in both conditions.

MLI axons express different subtypes of AMPARs

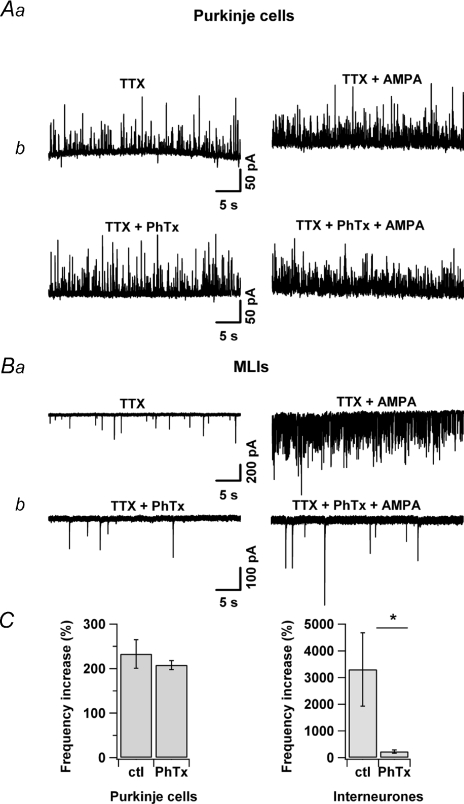

Taken together, our data differ from the findings of Rusakov et al. (2005) and Satake et al. (2004, 2006) who reported that the AMPA receptors in basket cell terminals were not Ca2+ permeable, and went on to describe an unconventional inhibitory mechanism mediated by an interaction between AMPA receptors and G proteins in these terminals. We therefore performed a series of experiments with the aim to clarify the source of these discrepancies. Following the protocol used by the Konishi laboratory (Satake et al. 2006), Purkinje cells were dialysed with a Cs+-based internal solution and voltage clamped at −30 mV, and TTX-insensitive mIPSCs were recorded. Under these conditions, AMPA modestly increased the frequency of mIPSCs (233 ± 32%, n= 3; Fig. 6Aa and C) and these responses were not affected by PhTx (1 μm; 208 ± 10 versus 233 ± 32, n= 3; see Fig. 6Ab and C), a specific blocker of Ca2+-permeable AMPARs (Tóth & McBain, 1998). These results are in total agreement with those reported by Satake et al. (2006) and suggest that Ca2+-permeable AMPARs do not contribute to the AMPA-mediated regulation of mIPSCs frequency at the basket cell–PC terminals. But when the mIPSCs were recorded in MLIs, following our experimental protocol (no Cs+, and potential held at −70 mV), the effects of AMPA were much more pronounced, and PhTx (1 μm) now strongly inhibited the AMPA (0.5 μm)-induced increase of mIPSCs frequency as depicted in Fig. 6Ba and b and summarized in Fig. 6C (229 ± 62%, n= 7 versus 3304 ± 1374%, n= 12; see Fig. 6Ab and C). These results confirm the presence of Ca2+-permeable AMPARs in MLI–MLI terminals and they suggest that MLI axons are able to express different subtypes of AMPARs, which are engaged in very different signalling pathways, depending on the type of postsynaptic cell they contact.

Figure 6. Ca2-permeable AMPARs in MLI-MLI terminals.

Aa, increase in the frequency of mIPSCs (upward deflections) in a PC held at +30 mV following application of AMPA (0.5 μm). Ab, the same result is observed in the presence of PhTx (1 μm). Ba, increase in the frequency of mIPSCs (downward deflections) in a MLI held at −70 mV following application of AMPA (0.5 μm). Bb, this effect is blocked in the presence of PhTx (1 μm). C, effects of PhTx (1 μm) on the AMPA (0.5 μm)-induced increases of frequency of mIPSCs recorded either from Purkinje cells (n= 3) or from MLIs (control: n= 12; PhTx: n= 7) as indicated underneath the graphs. Each column represents the mean ±s.e.m.

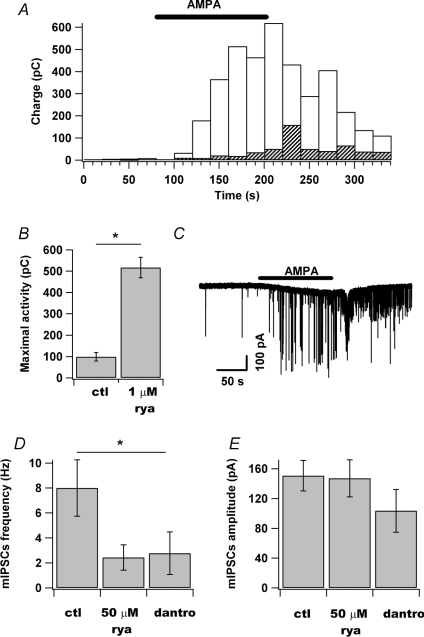

Ryanodine affects AMPA effects on mIPSCs

Presynaptic terminals of MLIs are known to contain ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ stores (RyCSs) that control the frequency and amplitude of miniature synaptic currents recorded in Purkinje cells (Llano et al. 2000; Conti et al. 2004). We therefore compared the response to 2 min bath application of AMPA (1 μm) in the presence of TTX in control conditions and after pretreatment with an excitatory concentration of ryanodine. In a first step, the effects of 1 μm ryanodine on MLI mIPSCs were examined in nine cells. The results show that ryanodine enhances mIPSC frequency (mean ratio to control, 1.30 ± 0.13, n= 9; not illustrated) but does not affect mIPSC amplitude (98 ± 20 versus 83 ± 16 pA, n= 9; P > 0.2 paired t test; not illustrated). These results confirm those obtained from MLI synaptic activity recorded in Purkinje cells under the same conditions (Llano et al. 2000). Altogether, the presence of ryanodine alone did not significantly modify the synaptic activity of MLI (16 ± 12 versus 25 ± 9 pC, n= 9; P > 0.05 paired t test). However, the response to AMPA was dramatically increased when cells were preincubated with ryanodine (517 ± 48 versus 99 ± 20 pC, n= 3; P < 0.05 t test; Fig. 7A and B). Interestingly, in the presence of ryanodine, application of AMPA produced high-frequency volleys of mEPSCs, that we refer to as a bursts, where maximal mEPSC frequency reached 21.4 ± 1.0 Hz (n= 4; Fig. 7C). These results suggest that Ca2+ flux through presynaptic AMPARs receptors leads to mobilization of store Ca2+ by Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) as was demonstrated in the case of neuronal nicotinic receptors (Sharma & Vijayaraghavan, 2003). We then tried to inhibit the Ca2+ release from Ca2+ stores with a high concentration of ryanodine (50 μm). The frequency of mIPSCs recorded in 50 μm ryanodine was 0.34 ± 0.10 Hz (n= 6) versus 0.34 ± 0.08 Hz (n= 12) in control conditions and the amplitude was 130 ± 13 versus 116 ± 17 pA (n= 6 and n= 12 respectively). When AMPA was added to the superfusate, the frequency of the mIPSCs reached 2.43 ± 1.02 Hz (n= 4), which is significantly lower than in control conditions (2.43 ± 1.02 versus 8.00 ± 2.26 Hz; n= 4, m= 12; P < 0.01 Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 7E). No gain in amplitude was observed when AMPA was added on top of a high concentration of ryanodine (147 ± 25 pA; n= 4). These data indicate that a high concentration of ryanodine limits the increase in mIPSC frequency triggered by AMPA. To confirm these results, we performed the same experiments with 10 μm dantrolene, a drug known to interact with RyR. It has been reported to reduce the proportion of time during which RyRs are open and thereby inhibit CICR (Ohta et al. 1990). Moreover, dantrolene can be considered as a better reagent than ryanodine for inhibiting purposes because it does not have a dual effect. The presence of dantrolene for more than 5 min did not significantly alter the frequency and the amplitude of mIPSCs in MLIs: 0.34 ± 0.16 Hz (n= 5) and 130 ± 13 pA (n= 6). In the presence of AMPA, the frequency of mIPSCs reached 2.78 ± 1.71 (n= 4) and the amplitude stayed at 104 ± 29 pA (n= 4). Altogether, our data summarized in Fig. 7E and F demonstrate that inhibiting Ca2+ release from Ca2+ stores diminishes the ability of AMPA to increase the frequency of the synaptic events. They confirm the involvement of Ca2+ stores in the presynaptic AMPA signalling. Finally, Ca2+ imaging experiments were performed in the presence of dantrolene (10 μm). AMPA puff experiments performed as explained earlier indicate that the peak Ca2+ signals recorded in axonal varicosities were inhibited by 38 ± 9% (n= 5) when dantrolene had been present for at least 5 min (not illustrated).

Figure 7. Ryanodine (1 μm) amplifies AMPA effects on GABAergic mIPSCs.

A, plot of the sum of the amplitude of all GABAergic synaptic events detected during 20 s sample intervals in control conditions (grey) or in the presence of ryanodine (1 μm; blank). The bar indicates the duration of AMPA (1 μm) application to the bath. B, summary of three experiments in control and in the presence of 1 μm ryanodine. C, typical recording of synaptic currents in the presence of ryanodine (1 μm) and AMPA (indicated by the bar above the current recording). Note the presence of a burst. D, effects of ryanodine (50 μm; n= 4) and dantrolene (10 μm; n= 4) on the AMPA (0.5 μm)-induced increases of mIPSC frequency recorded from MLIs (control: n= 12). E, effects of ryanodine (50 μm; rya 50; n= 4) and dantrolene (10 μm; dantro; n= 4) on the amplitude of mIPSCs in the presence of AMPA (0.5 μm; control: n= 12). For D and E, each column represents the mean ±s.e.m.

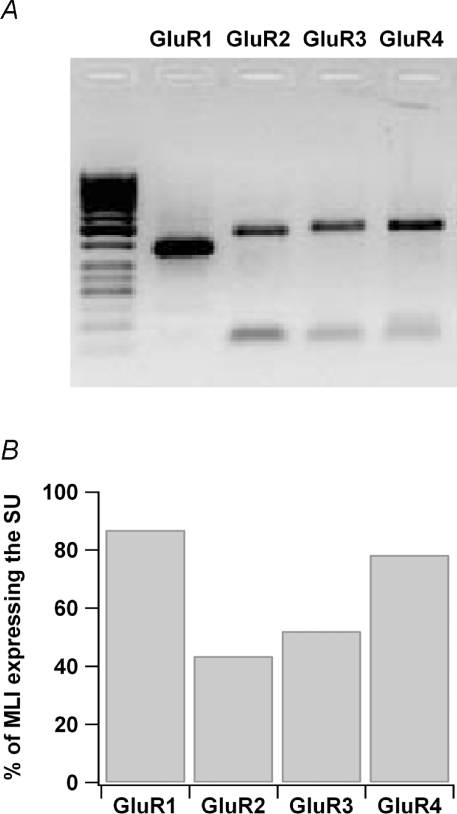

Expression of GluR1–4 subunits in MLIs

There are conflicting molecular biological and immunocytochemical results on the expression of AMPAR subunits in MLIs. Immunolabelling and electron microscopy studies concluded that the GluR1 and GluR4 subunits are not expressed in the interneurones (Petralia & Wenthold, 1992; Baude et al. 1994). The GluR3 subunit has been detected by in situ hybridization (Keinanen et al. 1990; Sato et al. 1993) and by the use of a common GluR2/3 antibody (Petralia & Wenthold, 1992) although a later report using the same antibody failed to detect it (Hafidi & Hillman, 1997). The only study carried out with a specific antibody against the GluR2 subunit did not reveal a labelling of the interneurones, but the authors mention that the quantity of protein might have been under the detection threshold (Petralia et al. 1997). Finally, the presence of the GluR4 subunit has been functionally deduced from studies using GluR4(–/–) mice (Gardner et al. 2005). In view of these fragmentary and partially contradictory results, we decided to re-examine the distribution of GluR subunits using single-cell RT-multiplex PCR. Such an experiment is depicted in Fig. 8A. In this example the mRNA for all the GluR1–4 subunits were detected, a result found in 9 out of 23 cells tested. In the other cells, either one or two GluR subunits were lacking. This is the first time that the GluR1 subunit has been detected in MLIs. Pooled results from the 23 cells are depicted on Fig. 8B. GluR2 was the least frequently expressed subunit. Thus our RT-PCR results concur with the earlier results obtained with immunolabelling to conclude that GluR2 is particularly weakly expressed in MLIs.

Figure 8. All AMPAR subunits are expressed in MLIs.

A, result of a RT-PCR experiment showing all subunits GluR1–4 expressed in a single MLI. B, summary of 23 RT-PCR experiments: percentage of MLIs expressing GluR1–4 subunits.

Discussion

This work indicates that AMPARs are present in axonal varicosities of MLIs and that they can be physiologically activated by glutamate liberated from PFs. Activation of these receptors induces Ca2+ entry both directly through the channel associated with the receptors, and indirectly, through depolarization-induced activation of VDCCs. By these two mechanisms, AMPARs support a powerful potentiation of GABAergic synaptic transmission between cerebellar interneurones that does not require AP firing.

Ca2+-permeable AMPARs are located in axonal varicosities

The experiments reported here demonstrate that AMPARs are present in the axonal varicosities which sustain large [Ca2+]i during AP firing, since the [Ca2+]i signals elicited by AMPA puffs in the presence of the broad range VDCC blocker Cd2+ are strictly colocalized with the AP-evoked [Ca2+]i signals. The use of Cd2+ allowed us also to assess the Ca2+ permeability of the AMPARs located in the varicosities and the contribution of VDCCs in AMPAR-mediated [Ca2+]i transients. The presence of Ca2+-permeable (GluR2-lacking) AMPARs in the axon was further confirmed by (i) the blocking effect of IEM 1460, (ii) the potentiating effect of CTZ, which significantly increased the Ca2+ response in the presence of Cd2+, and (iii) the blocking effect of PhTx on the AMPA-evoked increase in mIPSC frequency. The presence of GluR2 subunits on AMPAR confers minimal Ca2+-permeability (Dingledine et al. 1999; Isaac et al. 2007) and low sensitivity to block by IEM-1460 (Magazanik et al. 1997; Tikhonov et al. 2000). Finding that IEM-1460 inhibits both the AMPA-activated current and the ensuing [Ca2+]i signal reinforces our conclusion that some of the axonal AMPARs lack the GluR2 subunit.

AMPAR-mediated modulation of cerebellar inhibitory synapses

Our results on the increase in mIPSC frequency by AMPA in young rats are in accord with the initial observations of Bureau & Mulle (1998) who found a presynaptic modulation of mIPSCs in stellate cells from immature mice (PN 11–13) and with the report for a similar effect in young mice (Liu, 2007). Our Ca2+ imaging experiments with (PN 19–21) animals confirm the hypothesis of a developmental switch (Bureau & Mulle, 1998) that could correspond to a displacement of AMPARs from the axonal to the somato-dendritic compartment. Interestingly, it has been reported that presynaptic ionotropic glutamate receptors promote the maturation of GABAergic basket/stellate interneurones and increase the size of their axonal terminals thus enhancing GABA release (Fiszman et al. 2005, 2007). It seems likely that activation of presynaptic Ca2+-permeable AMPARs represents an important step in the developing cerebellum.

Recent evidence indicates that AP-induced transmitter release at central synapses can be modulated by ionotropic receptors. In the cerebellum, activation of presynaptic AMPARs leads to an inhibition of AP-dependent IPSCs. This inhibition was initially reported as a climbing fibre-induced modulation of the basket cell–PC synapse (Satake et al. 2000) and more recently it has been extended to a parallel fibre-mediated inhibition of the autaptic IPSCs recorded from stellate cells (Liu, 2007). In the case of the basket cell–PC synapse, the AMPA-induced inhibition is unaffected by PhTx, a blocker of Ca2+-permeable AMPARs (Tóth & McBain, 1998) and AMPA puffs lead to a decrease in AP-evoked [Ca2+]i signals at basket cell boutons onto PC somata (Rusakov et al. 2005). Liu (2007) claims that the difference between the regulation of spontaneous and evoked GABA release from MLI does not arise from the activation of distinct subtypes of AMPARs because both responses involve activation of Ca2+-impermeable AMPARs. This is not true. The potentiation of the spontaneous release of GABA from MLI has never been demonstrated to rely on Ca2+-impermeable AMPARs. The results we present here show that PhTx strongly inhibits the AMPA-induced increase of mIPSC frequency and confirm the presence of Ca2+-permeable AMPARs in MLI–MLI terminals. The question is now whether MLI axons are able to express different subtypes of AMPARs depending on the type of postsynaptic cell they contact. Rusakov et al. (2005) propose a mechanism underlying the reduction of Ca2+ entry through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels by a G-protein-coupled signalling involving AMPARs: this mechanism is still unknown. Metabotropic properties of AMPARs have been largely described (for review see Schenk & Matteoli, 2004) but they involve either an inhibition of PKA or an activation of MAPK, two pathways that cannot explain the suppression of evoked GABA release.

The Ca2+ permeability of GluR2-lacking AMPARs described here offers a route for Ca2+ entry independent of NMDARs or VDCCs (Isaac et al. 2007). One possible consequence of Ca2+ entry through presynaptic AMPARs could be PKC activation as recently reported for extrasynaptic NMDARs (Sun & Liu, 2007). Another possibility could be a sensitization of the presynaptic Ca2+ stores and a subsequent CICR process as was found with presynaptic NMDAR activation at the basket cell–Purkinje cell synapse (Duguid & Smart, 2004). In the hippocampus, presynaptic nicotinic receptor activation also elicits a CICR process at the mossy fibre–CA3 pyramidal neuron synapse (Sharma et al. 2003).

An amplification of the initial Ca2+ rise by Ca2+ stores is first suggested by the fact that the [Ca2+]i signals obtained by PF stimulation last longer than the evoked AMPA current (see Fig. 1). Second, the amplitude distribution of the mIPSCs became more homogeneous in the presence of low concentrations of AMPA. This effect was accompanied by an increase in the mIPSCs amplitude (Fig. 5C) together with a reduction in the CV values (Fig. 5D). In stellate cells, the IPSC amplitude distribution is skewed towards large events in control and TTX conditions, as observed for several synapses in the central nervous system (Edwards, 1995; Auger & Marty, 1997). A likely interpretation for the change in the shape of the distribution arises from the fact that in MLIs presynaptic Ca2+ stores sustaining CICR have been shown to generate multivesicular GABA release (Llano et al. 2000). We thus propose that Ca2+ influx through AMPARs and subsequent sensitization of the CICR process is responsible for the change in mIPSCs amplitude distribution. This type of amplification can explain that the dramatic effects of AMPA in terms of frequency and amplitude distribution are only accompanied by a small inward current, as mentioned by Bureau & Mulle (1998). A further piece of evidence supporting this hypothesis is that sensitization of RyCSs by a low concentration of ryanodine amplifies the effects of AMPA on the synaptic activity of MLIs (Fig. 6). RyCSs have been shown to be present in presynaptic terminals of MLIs where they control the frequency of miniature synaptic currents in the absence of spiking (Llano et al. 2000; Conti et al. 2004). Spontaneous release of Ca2+ from these RyCSs has been shown to be promoted by presynaptic NMDAR activation (Duguid & Smart, 2004). In the light of these data, the AMPA-mediated Ca2+ signal is likely to be amplified by CICR from RyCSs as it has been proposed at the synapse between rod bipolar cells and A17 amacrine cells (Chavez et al. 2006). Consequently, such a sustained increase in [Ca2+]i might lead to VDCC inactivation as proposed (Rusakov, 2006), which could at least partially explain the inhibitory effect of presynaptic AMPAR activation on evoked GABA release (Rusakov et al. 2005; Liu, 2007).

Expression of AMPARs subunit in MLIs

While activation of postsynaptic AMPARs or extrasynaptic NMDARs can induce a switch in synaptic AMPARs from GluR2-lacking (Ca2+-permeable) to GluR2-containing (Ca2+-impermeable) receptors (Liu & Cull-Candy, 2000, 2002, 2005; Sun & Liu, 2007), the subunit composition of the presynaptic AMPARs remains unknown. Previous studies concerning the expression of GluR(1–4) subunits in MLIs were based on in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry, and gave incomplete and apparently conflicting results. To summarize, MLIs were known to express GluR2/3/4 subunits and therefore Ca2+-permeable (GluR2-lacking) receptors were supposed to be formed as GluR2/4 hetero-oligomers (Keinanen et al. 1990; Sato et al. 1993; Baude et al. 1994; Hafidi & Hillman, 1997; Petralia et al. 1997; Gardner et al. 2005). Here we used a new approach (single-cell RT-PCR) and found that all of the GluR subunits are expressed. Among the four subunits tested, GluR2 was the least detected. This molecular study was carried out at PN 11–15 and the time window could be responsible for the low probability of GluR2 expression according to previous studies (Liu & Cull-Candy, 2002) that detailed the postsynaptic expression of GluR2. Finally, the presence of this subunit does not contradict our electrophysiological and imaging experiments since they concentrate on the presynaptic side of MLIs. The new single cell RT-PCR findings suggest that Ca2+-permeable receptors are likely to contain GluR1/3/4 subunits and our functional and pharmacological analysis further suggests that such channels predominate in the axons.

AMPARs activation increases the frequency and amplitude of mIPSCs

Additionally, we observe a change in the amplitude distribution of mIPSCs. In stellate cells, the IPSC amplitude distribution is skewed towards large events in control and TTX conditions, as observed for several synapses in the central nervous system (Edwards, 1995; Auger & Marty, 1997). Nevertheless, the amplitude distribution of the mIPSCs became more homogeneous in the presence of low concentrations of AMPA. This effect was accompanied by an increase in the mIPSC amplitude (Fig. 5C) together with a reduction in the CV values (Fig. 5D). A likely interpretation for the change in the shape of the distribution arises from the fact that in MLIs presynaptic Ca2+ stores sustaining CICR have been shown to generate multivesicular GABA release (Llano et al. 2000). We thus propose that Ca2+ influx through AMPARs and subsequent sensitization of the CICR process is responsible for the change in mIPSC amplitude distribution. This type of amplification can explain that the dramatic effects of AMPA in terms of frequency and amplitude distribution are only accompanied by a small inward current, as mentioned by Bureau & Mulle (1998). A further piece of evidence supporting this hypothesis is that sensitization of RyCSs by a low concentration of ryanodine amplifies the effects of AMPA the synaptic activity of MLIs (Fig. 6). RyCSs have been shown to be present in presynaptic terminals of MLIs where they control the frequency of miniature synaptic currents in the absence of spiking (Llano et al. 2000; Conti et al. 2004). Spontaneous release of Ca2+ from these RyCSs has been shown to be promoted by presynaptic NMDAR activation (Duguid & Smart, 2004). In the light of these data, the AMPA-mediated Ca2+ signal is likely to be amplified by CICR from RyCSs as it has been proposed at the synapse between rod bipolar cells and A17 amacrine cells (Chavez et al. 2006).

What physiological roles for presynaptic AMPARs at inhibitory central synapses?

The shape of the presynaptic AP is of fundamental importance in controlling the opening of VDCCs and consequently the Ca2+ signal that is available to trigger vesicle fusion (for review see Debanne, 2004). Therefore, the random nature of AP-independent transmitter release has resulted in the assumption that this process might not play a significant role in impulse propagation across synapses. However, it has been demonstrated at the hippocampal CA3–mossy fibre synapses that the Ca2+ released from intracellular stores, through a CICR process initiated by presynaptic a7-nAChRs, can lead to bursts of glutamate release in the absence of APs. These bursts of transmitter release being sufficient to drive the postsynaptic cell above threshold provide an AP-independent timing mechanism for impulse propagation (Sharma et al. 2003,08). The present results indicate that, at least in the GABAergic synapses investigated here, AMPARs are able to control the gain of the synaptic transmission. Burst activity in granule cells as recorded in response to sensory stimuli in vivo (Chadderton et al. 2004; Jörntell & Ekerot, 2006) is likely to activates presynaptic glutamate receptors on MLIs leading to an alteration of the presynaptic Ca2+ level. Such an alteration could modify the level of Ca2+ loading of Ca2+ stores making them prone to initiate CICR. Altogether, presynaptic AMPARs introduce an amplification step in the control of neurotransmitter release and provide new targets for regulations by surrounding glutamate sources.

Acknowledgments

We thank Isabel Llano and Alain Marty for their help throughout this work and their critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Gaëlle Revet for help with preparing the figures, the Centre National pour la Recherche Scientifique and the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche. B.R. is supported by a fellowship from the French Ministry for Research. We also like to thank Dr Michael Spedding for the kind gift of GYKI-53655.

Supplemental material

Online supplemental material for this paper can be accessed at:

http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2008.159921/DC1

References

- Atluri PP, Regehr WG. Delayed release of neurotransmitter from cerebellar granule cells. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8214–8227. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08214.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger C, Marty A. Heterogeneity of functional synaptic parameters among single release sites. Neuron. 1997;19:139–150. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahn S, Volk B, Wisden W. Kainate receptor gene expression in the developing rat brain. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5525–5547. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05525.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour B, Keller BU, Llano I, Marty A. Prolonged presence of glutamate during excitatory synaptic transmission to cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neuron. 1994;12:1331–1343. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baude A, Molnar E, Latawiec D, McIlhinney RA, Somogyi P. Synaptic and nonsynaptic localization of the GluR1 subunit of the AMPA-type excitatory amino acid receptor in the rat cerebellum. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2830–2843. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-02830.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baude A, Nusser Z, Roberts JD, Mulvihill E, McIlhinney RA, Somogyi P. The metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR1 alpha) is concentrated at perisynaptic membrane of neuronal subpopulations as detected by immunogold reaction. Neuron. 1993;11:771–787. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau I, Mulle C. Potentiation of GABAergic synaptic transmission by AMPA receptors in mouse cerebellar stellate cells: changes during development. J Physiol. 1998;509:817–831. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.817bm.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AG, Regehr WG. Prolonged synaptic currents and glutamate spillover at the parallel fiber to stellate cell synapse. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4423–4434. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04423.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadderton P, Margrie TW, Hausser M. Integration of quanta in cerebellar granule cells during sensory processing. Nature. 2004;428:856–860. doi: 10.1038/nature02442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez AE, Singer JH, Diamond JS. Fast neurotransmitter release triggered by Ca influx through AMPA-type glutamate receptors. Nature. 2006;12:705–708. doi: 10.1038/nature05123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophe E, Doerflinger N, Lavery DJ, Molnar Z, Charpak S, Audinat E. Two populations of layer v pyramidal cells of the mouse neocortex: development and sensitivity to anaesthetics. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:3357–3367. doi: 10.1152/jn.00076.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin T, Chat M, Lucas MG, Moreno H, Racay P, Schwaller B, Marty A, Llano I. Developmental changes in parvalbumin regulate presynaptic Ca2+ signaling. J Neurosci. 2005;25:96–107. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3748-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti R, Tan YP, Llano I. Action potential-evoked and ryanodine-sensitive spontaneous Ca2+ transients at the presynaptic terminal of a developing CNS inhibitory synapse. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6946–6957. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1397-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cull-Candy S, Kelly L, Farrant M. Regulation of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors: synaptic plasticity and beyond. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D. Information processing in the axon. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:304–316. doi: 10.1038/nrn1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duguid IC, Smart TG. Retrograde activation of presynaptic NMDA receptors enhances GABA release at cerebellar interneurone-Purkinje cell synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:525–533. doi: 10.1038/nn1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FA. Anatomy and electrophysiology of fast central synapses lead to a structural model for long-term potentiation. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:759–787. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.4.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman HS, MacDermott AB. Presynaptic ionotropic receptors and control of transmitter release. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:135–145. doi: 10.1038/nrn1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiszman ML, Barberis A, Lu C, Fu Z, Erdélyi F, Szabó G, Vicini S. NMDA receptors increase the size of GABAergic terminals and enhance GABA release. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2024–2031. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4980-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiszman ML, Erdélyi F, Szabó G, Vicini S. Presynaptic AMPA and kainate receptors increase the size of GABAergic terminals and enhance GABA release. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:1631–1640. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forti L, Pouzat C, Llano I. Action potential-evoked Ca2+ signals and calcium channels in axons of developing rat cerebellar interneurones. J Physiol. 2000;527:33–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner SM, Takamiya K, Xia J, Suh JG, Johnson R, Yu S, Huganir RL. Calcium-permeable AMPA receptor plasticity is mediated by subunit-specific interactions with PICK1 and NSF. Neuron. 2005;45:903–915. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glitsch M, Marty A. Presynaptic effects of NMDA in cerebellar Purkinje cells and interneurones. J Neurosci. 1999;19:511–519. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00511.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafidi A, Hillman DE. Distribution of glutamate receptors GluR 2/3 and NR1 in the developing rat cerebellum. Neuroscience. 1997;81:427–436. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlitze S, Raditsch M, Ruppersberg JP, Jahn W, Monyer H, Schoepfer R, Witzemann V. Argiotoxin detects molecular differences in AMPA receptor channels. Neuron. 1993;10:1131–1140. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90061-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac JT, Ashby M, McBain CJ. The role of the GluR2 subunit in AMPA receptor function and synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2007;54:859–871. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jörntell H, Ekerot CF. Properties of somatosensory synaptic integration in cerebellar granule cells in vivo. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11786–11797. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2939-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakossian MH, Otis TS. Excitation of cerebellar interneurones by group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:1558–1565. doi: 10.1152/jn.00300.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keinanen K, Wisden W, Sommer B, Werner P, Herb A, Verdoorn TA, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH. A family of AMPA-selective glutamate receptors. Science. 1990;249:556–560. doi: 10.1126/science.2166337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SJ. Biphasic modulation of GABA release from stellate cells by glutamatergic receptor subtypes. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:550–556. doi: 10.1152/jn.00352.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SQ, Cull-Candy SG. Synaptic activity at calcium-permeable AMPA receptors induces a switch in receptor subtype. Nature. 2000;405:454–458. doi: 10.1038/35013064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SJ, Cull-Candy SG. Activity-dependent change in AMPA receptor properties in cerebellar stellate cells. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3881–3889. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-10-03881.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SJ, Cull-Candy SG. Subunit interaction with PICK and GRIP controls Ca2+ permeability of AMPARs at cerebellar synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:768–775. doi: 10.1038/nn1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SJ, Lachamp P. The activation of excitatory glutamate receptors evokes a long-lasting increase in the release of GABA from cerebellar stellate cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9332–9339. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2929-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano I, Gerschenfeld HM. Inhibitory synaptic currents in stellate cells of rat cerebellar slices. J Physiol. 1993;468:177–200. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano I, Gonzalez J, Caputo C, Lai FA, Blayney LM, Tan YP, Marty A. Presynaptic calcium stores underlie large-amplitude miniature IPSCs and spontaneous calcium transients. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1256–1265. doi: 10.1038/81781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magazanik LG, Buldakova SL, Samoilova MV, Gmiro VE, Mellor IR, Usherwood PN. Block of open channels of recombinant AMPA receptors and native AMPA/kainite receptors by adamantane derivatives. J Physiol. 1997;505:655–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.655ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejia-Gervacio S, Collin T, Pouzat C, Tan YP, Llano I, Marty A. Axonal speeding: shaping synaptic potentials in small neurons by the axonal membrane compartment. Neuron. 2007;53:843–855. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monyer H, Burnashev N, Laurie DJ, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH. Developmental and regional expression in the rat brain and functional properties of four NMDA receptors. Neuron. 1994;12:529–540. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta T, Ito S, Ohga A. Inhibitory action of dantrolene on Ca-induced Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum in guinea pig skeletal muscle. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990;178:11–19. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)94788-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partin KM, Fleck MW, Mayer ML. AMPA receptor flip/flop mutants affecting deactivation, desensitization, and modulation by cyclothiazide, aniracetam, and thiocyanate. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6634–6647. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-06634.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partin KM, Patneau DK, Winters CA, Mayer ML, Buonanno A. Selective modulation of desensitization at AMPA versus kainate receptors by cyclothiazide and concanavalin A. Neuron. 1993;11:1069–1082. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90220-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petralia RS, Wang YX, Mayat E, Wenthold RJ. Glutamate receptor subunit 2-selective antibody shows a differential distribution of calcium-impermeable AMPA receptors among populations of neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1997;385:456–476. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970901)385:3<456::aid-cne9>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petralia RS, Wenthold RJ. Light and electron immunocytochemical localization of AMPA-selective glutamate receptors in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1992;318:329–354. doi: 10.1002/cne.903180309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusakov DA. Ca2+-dependent mechanisms of presynaptic control at central synapses. Neuroscientist. 2006;12:317–326. doi: 10.1177/1073858405284672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusakov DA, Saitow F, Lehre KP, Konishi S. Modulation of presynaptic Ca2+ entry by AMPA receptors at individual GABAergic synapses in the cerebellum. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4930–4940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0338-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satake S, Saitow F, Yamada J, Konishi S. Synaptic activation of AMPA receptors inhibits GABA release from cerebellar interneurones. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:551–558. doi: 10.1038/75718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satake S, Saitow F, Rusakov D, Konishi S. AMPA receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition at cerebellar GABAergic synapses: a characterization of molecular mechanisms. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:2464–2474. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satake S, Song SY, Cao Q, Satoh H, Rusakov DA, Yanagawa Y, Ling EA, Imoto K, Konishi S. Characterization of AMPA receptors targeted by the climbing fiber transmitter mediating presynaptic inhibition of GABAergic transmission at cerebellar interneurone-Purkinje cell synapses. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2278–2289. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4894-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Kiyama H, Tohyama M. The differential expression patterns of messenger RNAs encoding non-N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptor subunits (GluR1–4) in the rat brain. Neuroscience. 1993;52:515–539. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90403-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk U, Matteoli M. Presynaptic AMPA receptors: more than just ion channels? Biol Cell. 2004;96:257–260. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma G, Vijayaraghavan S. Modulation of presynaptic store calcium induces release of glutamate and postsynaptic firing. Neuron. 2003;38:929–939. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00322-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Liu SJ. Activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors induces a PKC-dependent switch in AMPA receptor subtypes in mouse cerebellar stellate cells. J Physiol. 2007;583:537–553. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.136788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan YP, Llano I. Modulation by K+ channels of action potential-evoked intracellular Ca2+ concentration rises in rat cerebellar basket cell axons. J Physiol. 1999;520:65–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonov DB, Samoilova MV, Buldakova SL, Gmiro VE, Magazanik LG. Voltage-dependent block of native AMPA receptor channels by dicationic compounds. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:265–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth K, McBain CJ. Afferent-specific innervation of two distinct AMPA receptor subtypes on single hippocampal interneurones. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:572–578. doi: 10.1038/2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trussell LO, Zhang S, Raman IM. Desensitization of AMPA receptors upon multiquantal neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1993;10:1185–1196. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90066-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn MS, Numberger M, Zhang S, Dingledine R. Differential dependence on GluR2 expression of three characteristic features of AMPA receptors. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9393–9406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-24-09393.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada KA, Tang CM. Benzothiadiazides inhibit rapid glutamate receptor desensitization and enhance glutamatergic synaptic currents. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3904–3915. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-09-03904.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.