Summary

Recurrent somatic ASXL1 mutations occur in patients with myelodysplasia (MDS), myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN), and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and are associated with adverse outcome. Despite the genetic and clinical data implicating ASXL1 mutations in myeloid malignancies, the mechanisms of transformation by ASXL1 mutations are not understood. Here we identify that ASXL1 mutations result in loss of PRC2-mediated histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27) tri-methylation. Through integration of microarray data with genome-wide histone modification ChIP-Seq data we identify targets of ASXL1 repression including the posterior HOXA cluster that is known to contribute to myeloid transformation. We demonstrate that ASXL1 associates with the Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), and that loss of ASXL1 in vivo collaborates with NRASG12D to promote myeloid leukemogenesis.

Introduction

Recent genome-wide and candidate-gene discovery efforts have identified a series of novel somatic genetic alterations in patients with myeloid malignancies with relevance to pathogenesis, prognostication, and/or therapy. Notably, these include mutations in genes with known or putative roles in the epigenetic regulation of gene transcription. One such example are mutations in the gene Addition of sex combs-like 1 (ASXL1), which is mutated in ≈15–25% of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and ≈10–15% of patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (Abdel-Wahab et al., 2011; Bejar et al., 2011; Gelsi-Boyer et al., 2009). Clinical studies have consistently indicated that mutations in ASXL1 are associated with adverse survival in MDS and AML (Bejar et al., 2011; Metzeler et al., 2011; Pratcorona et al., 2011; Thol et al., 2011).

ASXL1 is the human homologue of Drosophila Additional sex combs (Asx). Asx deletion results in a homeotic phenotype characteristic of both Polycomb (PcG) and Trithorax group (TxG) gene deletions (Gaebler et al., 1999) which led to the hypothesis that Asx has dual functions in silencing and activation of homeotic gene expression. In addition, functional studies in Drosophila suggested that Asx encodes a chromatin-associated protein with similarities to PcG proteins (Sinclair et al., 1998). More recently, it was demonstrated that Drosophila Asx forms a complex with the chromatin deubiquitinase Calypso to form the Polycomb-repressive deubiquitinase (PR-DUB) complex, which removes monoubiquitin from histone H2A at lysine 119. The mammalian homologue of Calypso, BAP1, directly associates with ASXL1, and the mammalian BAP1-ASXL1 complex was shown to possess deubiquitinase activity in vitro (Scheuermann et al., 2010).

The mechanisms by which ASXL1 mutations contribute to myeloid transformation have not been delineated. A series of in vitro studies in non-hematopoietic cells have suggested a variety of activities for ASXL1 including physical cooperativity with HP1a and LSD1 to repress retinoic acid-receptor activity and interaction with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARg) to suppress lipogenesis (Cho et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2010; Park et al., 2011). In addition, a recent study using a gene-trap model reported that constitutive disruption of Asxl1 results in significant perinatal lethality, however the authors did not note alterations in stem/progenitor numbers in surviving Asxl1 gene trap mice (Fisher et al., 2010; Fisher et al., 2009). Importantly, the majority of mutations in ASXL1 occur as nonsense mutations and insertions/deletions proximal or within the last exon prior to the highly conserved PHD domain. It is currently unknown whether mutations in ASXL1 might confer a gain-of-function due to expression of a truncated protein, or whether somatic loss of ASXL1 in hematopoietic cells leads to specific changes in epigenetic state, gene expression, or hematopoietic functional output. The goals of this study were to determine the effects of ASXL1 mutations on ASXL1 expression as well as the transcriptional and biological effects of perturbations in ASXL1 which might contribute towards myeloid transformation.

Results

ASXL1 mutations result in loss of ASXL1 expression

ASXL1 mutations in patients with MPN, MDS, and AML most commonly occur as somatic nonsense mutations and insertion/deletion mutations in a clustered region adjacent to the highly conserved PHD domain (Abdel-Wahab et al., 2011; Gelsi-Boyer et al., 2009). To assess whether these mutations result in loss of ASXL1 protein expression or in expression of a truncated isoform, we performed Western blots using N- and C-terminal anti-ASXL1 antibodies in a panel of human myeloid leukemia cell lines and primary AML samples which are wildtype or mutant for ASXL1. We found that myeloid leukemia cells with homozygous frameshift/nonsense mutations in ASXL1 (NOMO1 and KBM5) have no detectable ASXL1 protein expression (Figure 1A). Similarly, leukemia cells with heterozygous ASXL1 mutations have reduced or absent ASXL1 protein expression. Western blot analysis of ASXL1 using an N-terminal anti-ASXL1 antibody in primary AML samples wildtype and mutant for ASXL1 revealed reduced/absent full-length ASXL1 expression in samples with ASXL1 mutations compared to ASXL1 wildtype samples (Figure S1A). Importantly, we did not identify truncated ASXL1 protein products in mutant samples using N- or C-terminal directed antibodies in primary AML samples or leukemia cell lines. Moreover, expression of wildtype ASXL1 cDNA or cDNA constructs bearing leukemia-associated mutant forms of ASXL1 revealed reduced stability of mutant forms of ASXL1 relative to wildtype ASXL1, with more rapid degradation of mutant ASXL1 isoforms following cycloheximide exposure (Figure S1B). These data are consistent with ASXL1 functioning as a tumor suppressor with loss of ASXL1 protein expression in leukemia cells with mutant ASXL1 alleles.

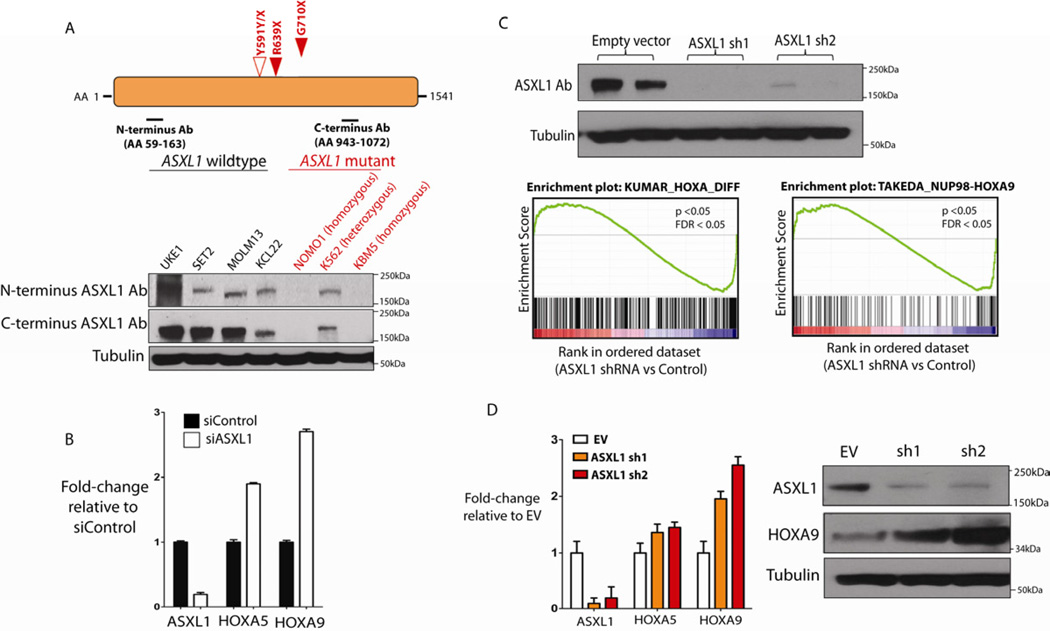

Figure 1. Leukemogeneic ASXL1 mutations are loss-of-function mutations and ASXL1 loss is associated with upregulation of HOXA gene expression.

Characterization of ASXL1 expression in leukemia cells with nonsense mutations in ASXL1 reveals loss of ASXL1 expression at the protein level in cells with homozygous ASXL1 mutations as shown by Western blotting using N- and C-terminal anti-ASXL1 antibodies (A). Displayed are the ASXL1-mutant cell line lines NOMO1 (homozygous ASXL1 R639X), K562 (heterozygous ASXL1 Y591Y/X), and KBM5 (heterozygous ASXL1 G710X) and a panel of ASXL1-wildtype cell lines. ASXL1 siRNA in human primary CD34+ cells form cord blood results in upregulation of HOXA5 and HOXA9 with ASXL1 knockdown (KD) as revealed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR analysis) (B). Stable KD of ASXL1 in ASXL1-wildype transformed human myeloid leukemia UKE1 cells (as shown by Western Blot) followed by Gene Set Enrichment Analysis reveals significant enrichment of gene sets characterized by upregulation of 5’ HOXA genes (C) as was confirmed by qRT-PCR (D). Statistical significance is indicated by the p-value and false-discovery rate (FDR). Similar upregulation of HOXA9 is seen by Western Blot following stable ASXL1 knockdown in the ASXL1-wildtype human leukemia SET2 cells (D). Error bars represent standard deviation of expression relative to control. See also Figure S1, Table S1, and Table S2.

ASXL1 knockdown in hematopoietic cells results in upregulated HOXA gene expression

Given that ASXL1 mutations result in loss of ASXL1 expression we investigated the effects of ASXL1 knockdown in primary hematopoietic cells. We used a pool of small interfering RNAs (siRNA) to perform knockdown (KD) of ASXL1 in primary human CD34+ cells isolated from umbilical cord blood. ASXL1 KD was performed in triplicate and confirmed by qRT-PCR analysis (Figure 1B), followed by gene-expression microarray analysis. Gene-set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of this microarray data revealed a significant enrichment of genes found in a previously described gene expression signature of leukemic cells from bone marrow of MLL-AF9 knock-in mice (Kumar et al., 2009) as well as highly significant enrichment of a gene signature found in primary human cord blood CD34+ cells expressing NUP98-HOXA9 (Figure S1C and Table S1) (Takeda et al., 2006). Specifically, we found that ASXL1 knockdown in human primary CD34+ cells resulted in increased expression of 145 genes out of the 279 genes which are overexpressed in the MLL-AF9 gene expression signature (p<0.05, FDR<0.05). These gene expression signatures are characterized by increased expression of posterior HOXA cluster genes, including HOXA5-9.

In order to ascertain whether loss of ASXL1 was associated with similar transcriptional effects in leukemia cells, we performed shRNA-mediated stable knockdown of ASXL1 in the ASXL1-wildtype human leukemia cell lines UKE1 (Figure 1C and Figure 1D) and SET2 (Figure 1D) followed by microarray and qRT-PCR analysis. Gene expression analysis in UKE-1 cells expressing ASXL1 shRNA compared to control cells revealed significant enrichment of the same HOXA gene expression signatures as were seen with ASXL1 KD in CD34+ cells (Figure 1C and Table S2). Upregulation of 5’ HOXA genes was confirmed by qRT-PCR in UKE1 (Figure 1D) cells and by Western blot analysis (Figure 1D) in SET2 cells expressing ASXL1 shRNA compared to control. Quantitative mRNA profiling (Nanostring nCounter) of the entire HOXA cluster revealed upregulation of multiple HOXA members, including HOXA5, 7, 9, and 10, in SET2 cells with ASXL1 KD compared to control cells (Figure S1D). These results indicate consistent upregulation of HOXA gene expression following ASXL1 loss in multiple hematopoietic contexts.

ASXL1 forms a complex with BAP1 in leukemia cells, but BAP1 loss does not upregulate HoxA gene expression in hematopoietic cells

Mammalian ASXL1 forms a protein complex in vitro with the chromatin deubiquitinase BAP1, which removes monoubiquitin from histone H2A at lysine 119 (H2AK119) (Scheuermann et al., 2010). In Drosophila loss of either Asx or Calypso resulted in similar effects on genome-wide H2AK119 ubiquitin levels and on target gene expression. Recent studies have revealed recurrent germline and somatic loss-of-function BAP1 mutations in mesothelioma and uveal melanoma (Bott et al., 2011; Harbour et al., 2010; Testa et al., 2011). However we have not identified BAP1 mutations in MPN or AML patients (OAW, JP and RLL unpublished data). Co-immunopreciptation (co-IP) studies revealed an association between ASXL1 and BAP1 in human myeloid leukemia cells wildtype for ASXL1 but not in those cells mutant for ASXL1 due to reduced/absent ASXL1 expression (Figure 2A). Immunoprecipitation of FLAG-tagged wildtype ASXL1 and FLAG-tagged leukemia-associated mutant forms of ASXL1 revealed reduced interaction between mutant forms of ASXL1 and endogenous BAP1 (Figure S2A). Despite these findings, BAP1 knockdown did not result in upregulation of HOXA5 and HOXA9 in UKE1 cells, although a similar extent of ASXL1 knockdown in the same cells reproducibly increased HOXA5 and HOXA9 expression (Figure 2B). We obtained similar results with knockdown of Asxl1 or Bap1 in the Ba/F3 murine hematopoietic cell line (Figure 2C). In Ba/F3 cells, KD of Asxl1 resulted in upregulated Hoxa9 gene expression commensurate with the level of Asxl1 downregulation whereas knockdown of Bap1 not impact Hoxa expression (Figure 2C). ASXL1 KD in SET-2 cells failed to reveal an effect of ASXL1 loss on H2AK119Ub levels as assessed by Western blot of purified histones from shRNA control and ASXL1 KD cells (Figure S2B). By contrast SET2 cells treated with MG132 (25uM) had a marked decrease in H2AK119Ub, as has been previously described (Dantuma et al., 2006). These data suggest ASXL1 loss contributes to myeloid transformation through a BAP1-independent mechanism.

Figure 2. ASXL1 and BAP1 physically interact in human hematopoietic cells but BAP1 loss does not result in increased HoxA gene expression.

Immunoprecipitation of BAP1 in a panel of ASXL1-wildtype and mutant human myeloid leukemia cells reveals co-association of ASXL1 and BAP1 (A). Cells with heterozygous or homozygous mutations in ASXL1 with reduced or absent ASXL1 expression have minimal interaction with BAP1 in vitro. BAP1 knockdown in the ASXL1/BAP1 wildtype human leukemia cell line UKE1 fails to alter HOXA gene expression (B). In contrast, stable knockdown of ASXL1 in the same cell type results in a significant upregulation of HOXA9. Similar results are seen with knockdown of Asxl1 or Bap1 in murine precursor-B lymphoid Ba/F3 cells (C). Error bars represent standard deviation of expression relative to control. See also Figure S2.

Loss of ASXL1 is associated with global loss of H3K27me3

The results described above led us to hypothesize that ASXL1 loss leads to BAP1-independent effects on chromatin state and on target gene expression. To assess the genome-wide effects of ASXL1 loss on chromatin state we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by next generation sequencing (CHIP-seq) for histone modifications known to be associated with PcG (histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3)) or TxG activity (histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3)) in UKE1 cells expressing empty vector (EV) or 2 independent validated shRNAs for ASXL1. ChIP-Seq data analysis revealed a significant reduction in genome-wide H3K27me3 transcriptional start site (TSS) occupancy with ASXL1 KD compared to EV (p=2.2 × 10−16 Figure 3A). Approximately 20% of genes (n= 4686) were marked by the H3K27me3 modification in their promoter regions (defined as 1.5 kb downstream and 0.5 kb upstream of the TSS). Among H3K27me3 marked genes, 27% had a 2-fold reduction in H3K27me3 (n=1309) and 66% had a 1.5 fold reduction in H3K27me3 (n=3,092) respectively, upon ASXL1 KD. No significant effect was seen on H3K4me3 TSS occupancy with ASXL1 depletion (Figure 3A). We next evaluated whether loss of ASXL1 might be associated with loss of H3K27me3 globally by performing Western blot analysis on purified histones from UKE1 cells transduced with EV or shRNAs for ASXL1 KD. This analysis revealed a significant decrease in global H3K27me3 with ASXL1 loss (Figure 3B) despite preserved expression of the core PRC2 members EZH2, SUZ12, and EED. Similar effects on total H3K27me3 levels were seen following Asxl1 KD in Ba/F3 cells (Figure S3A). These results demonstrate that ASXL1 depletion leads to a marked reduction in genome-wide H3K27me3 in hematopoietic cells.

Figure 3. ASXL1 loss is associated with loss of H3K27me3 and with increased expression of genes poised for transcription.

ASXL1 loss is associated with a significant genome-wide decrease in H3K27me3 as illustrated by box plot showing the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles for H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 enrichment at transcription start sites in UKE1 cells treated with an empty vector or shRNAs directed against ASXL1 (A). The whiskers indicate the most extreme data point less than 1.5 interquartile range from box and red bar represents the median. Loss of ASXL1 is associated with a global loss of H3K27me3 without affecting PRC2 component expression as shown by Western blot of purified histones from cells with UKE1 knockdown and Western blot for core PRC2 component in whole cell lysates from ASXL1 knockdown UKE1 cells (B). Loss of H3K27me3 is evident at the HOXA locus as shown by ChIP-Seq promoter track signals across the HOXA locus in UKE1 cells treated with an EV or shRNA knockdown of ASXL1 (C). H3K27me3 ChIP-Seq promoter track signals from HOXA5 to HOXA13 in UKE1 cells treated with shRNA control or one of 2 anti-ASXL1 shRNAs is shown in (D) with location of primers used in ChIP-quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR) validation. ChIP for H3K27me3 and H2AK119Ub followed by ChIP-qPCR in cells treated with control or ASXL1 knockdown confirms a significant decrease in H3K27me3 at the HOXA locus with ASXL1 KD but minimal effects of ASXL1 KD on H2AK119Ub levels at the same primer locations (D). Integrating gene-expression data with H3K27me3/H3K4me3 ChIP-Seq identifies a significant correlation between alterations in chromatin state and increases in gene expression following ASXL1 loss at loci normally marked by the simultaneous presence of H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 in control cells (E). Loss of H3K27me3 is seen at promoters normally marked by the presence of H3K27me3 alone or at promoters co-occupied by H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 in the control state (F). See also Figure S3.

Detailed analysis of CHIP-seq data revealed that genomic regions marked by large H3K27me3 domains in control cells displayed more profound loss of H3K27me3 upon loss of ASXL1. Genome-wide analysis of the ChIP-Seq data from control and ASXL1 shRNA treated cells revealed that the sites that lose H3K27me3 in the ASXL1 KD cells were on average 6,591 nucleotides in length, while the sites that maintained H3K27me3 were on average 3,123 nucleotides in length (p<10−16) (Figure S3B). This is visually illustrated by the reduction in H3K27me3 at the posterior HOXA cluster (Figure 3C) and at the HOXB and HOXC loci (Figure S3C). The association of ASXL1 loss with loss of H3K27me3 abundance at the HOXA locus was confirmed by ChIP for H3K27me3 in control and ASXL1 KD cells followed by qPCR (ChIP-qPCR) across the HOXA locus (Figure 3D). ChIP-qPCR in control and KD cells revealed a modest increase in H2AK119Ub with ASXL1 loss at the HOXA locus (Figure 3D), in contrast to the more significant reduction in H3K27me3. In contrast to the large decrease in H3K27me3 levels at the HOXA locus with ASXL1 KD, a subset of loci had much less significant reduction in H3K27me3, in particular at loci whose promoters were marked by sharp peaks of H3K27me3 (Figure S3D). Intersection of gene expression and ChIP-Seq data revealed that genes overexpressed in ASXL1 KD cells were simultaneously marked with both activating (H3K4me3) and repressive (H3K27me3) domains in control cells (Figures 3E and 3F). This finding suggests that the transcriptional repression mediated by ASXL1 in myeloid cells is most apparent at loci poised for transcription with bivalent chromatin domains. Indeed, the effects of ASXL1 loss on H3K27me3 occupancy were most apparent at genes whose promoters were marked by the dual presence of H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 (Figure 3F). We cannot exclude the possibility that H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 exist in different populations within the homogeneous cell lines being studied, but the chromatin and gene expression data are consistent with an effect of ASXL1 loss on loci with bivalent chromatin domains (Bernstein et al., 2006; Mikkelsen et al., 2007).

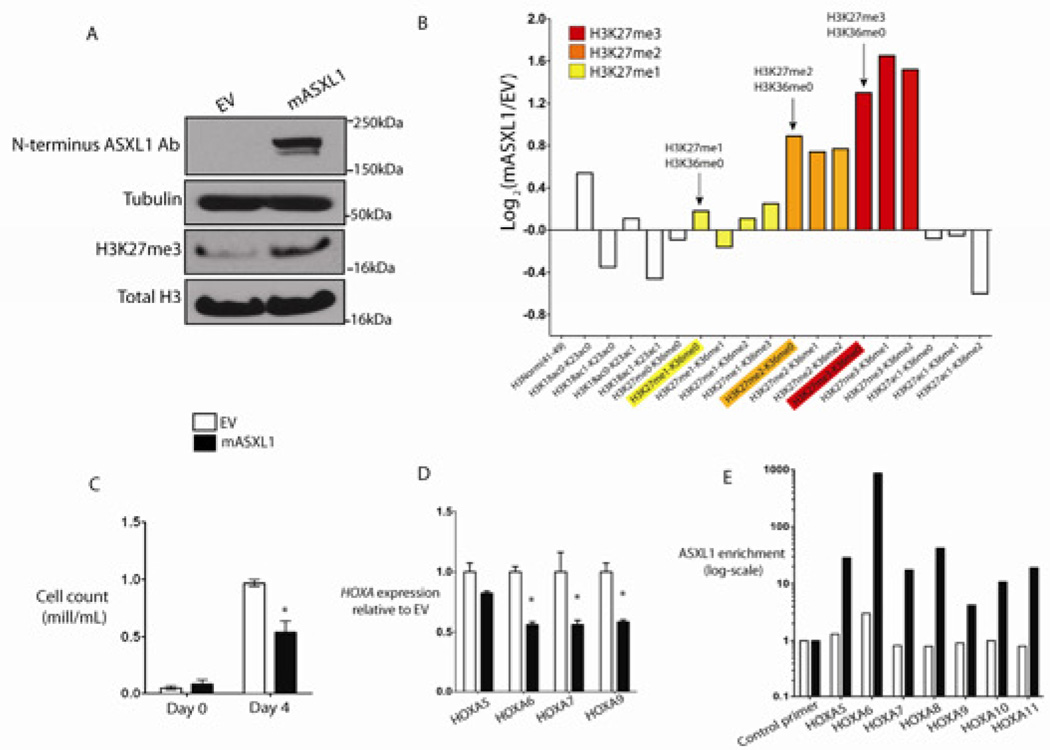

Enforced expression of ASXL1 in leukemic cells results in suppression of HOXA gene expression, a global increase in H3K27me3, and growth suppression

We next investigated whether reintroduction of wildtype ASXL1 protein could restore H3K27me3 levels in ASXL1-mutant leukemia cells. We stably expressed wild-type ASXL1 in NOMO1 and KBM5 cells, homozygous ASXL1-mutant human leukemia cell lines which do not express ASXL1 protein (Figure 4A and Figure S4A). ASXL1 expression resulted in a global increase in H3K27me3 as assessed by histone Western blot analysis (Figure 4A). Liquid-chromotography/mass spectrometry of purified histones in NOMO1 cells expressing ASXL1 confirmed a ~2.5-fold increase in trimethylated H3K27 peptide and significant increases in mono- and dimethylated H3K27 in NOMO1 cells expressing ASXL1 compared to EV control. (Figure 4B). ASXL1 add-back resulted in growth suppression (Figure 4C) and in decreased HOXA gene expression in NOMO1 cells (Figure 4D). ASXL1 add-back similarly resulted in decreased expression of HOXA target genes in KBM5 cells (Figure S4A and S4B). CHIP-qPCR revealed a strong enrichment in ASXL1 binding at the HOXA locus in NOMO1 cells expressing ASXL1, demonstrating that the HOXA locus is a direct target of ASXL1 in hematopoietic cells (Figure 4E).

Figure 4. Expression of ASXL1 in ASXL1-null leukemic cells results in global increase in H3K27me2/3, growth suppression, and suppression of HoxA gene expression.

ASXL1 expression in ASXL1-null NOMO1 cells is associated with a global increase in H3K27me3 as detected by Western blot of purified histones (A) as well as by quantitative liquid-chromatography/mass spectrometry of H3 peptides from amino acids 18–40 (B) (arrows indicate quantification of H3K27me1/2/3). ASXL1 overexpression results in growth suppression in 7-day growth assay performed in triplicate (C). Overexpression of ASXL1 was associated with a decrement in posterior HoxA gene expression in NOMO1 cells as shown by qRT-PCR for HOXA5, 6, 7, and 9 (D). This downregulation in HOXA gene expression was concomitant with a strong enrichment of ASXL1 at the loci of these genes as shown by chromatin immunoprecipitation of ASXL1 followed by quantitative PCR with BCRRP1 as a control locus. (E). Error bars represent standard deviation of target gene expression relative to control. See also Figure S4.

ASXL1 loss leads to exclusion of H3K27me3 and EZH2 from the HoxA cluster consistent with a direct effect of ASXL1 on PRC2 recruitment

We next investigated whether the effects of ASXL1 loss on H3K27me3 was due to inhibition of PRC2 recruitment to specific target loci. ChIP-qPCR for H3K27me3 in SET2 cells with ASXL1 knockdown or control revealed a loss of H3K27me3 enrichment at the posterior HoxA locus with ASXL1 knockdown (Figures 5A and 5B). We observed a modest, variable increase in H3K4me3 enrichment at the HOXA locus with ASXL1 depletion in SET2 cells (Figure 5C). We similarly assessed H3K27me3 enrichment in primary bone marrow leukemic cells from AML patients wildtype and mutant for ASXL1 which likewise revealed decreased H3K27me3 enrichment across the HOXA cluster in primary AML samples with ASXL1 mutations compared to ASXL1-wildtype AML samples (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. ASXL1 loss is associated with loss of PRC2 recruitment at the HOXA locus.

Chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP) for H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 followed by next-generation sequencing reveals the abundance and localization of H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 at the HoxA locus in SET2 cells (A). ChIP for H3K27me3 (B) and H3K4me3 (C) followed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) across the 5’ HOXA locus in SET2 cells treated with an empty vector or stable knockdown of ASXL1 reveals a consistent downregulation of H3K27me3 across the 5’ HOXA locus following ASXL1 loss and a modest increase in H3K4me3 at the promoters of 5’ HOXA genes with ASXL1 loss (primer locations are shown in A). Similar ChIP for H3K27me3 followed by qPCR across the HOXA locus in primary leukemic blasts from 2 patients with ASXL1 mutations versus 2 without ASXL1 mutations reveals H3K27me3 loss across the HOXA locus in ASXL1 mutant cells (D). ChIP for EZH2 followed by qPCR at the 5’ end of HOXA locus in SET2 cells reveals loss of EZH2 enrichment with ASXL1 loss in SET2 cells (E). CHIP-qPCR was performed in biologic duplicates and ChIP-qPCR data is displayed as enrichment relative to input. qPCR at the gene body of RRP1, a region devoid of H3K4me3 or H3K27me3, is utilized as a control locus. The error bars represent standard deviation.

Given the consistent effects of ASXL1 depletion on H3K27me3 abundance at the HOXA locus, we then evaluated the occupancy of EZH2, a core PRC2 member, at the HoxA locus. ChIP-Seq for H3K27me3 in native SET2 and UKE1 cells identified that H3K27me3 is present with a dome-like enrichment pattern at the 5’ end of the posterior HOXA cluster (Figure 5A); CHIP-qPCR revealed that EZH2 is prominently enriched in this same region in parental SET2 cells (Figure 5E). Importantly, ASXL1 depletion resulted in loss of EZH2 enrichment at the HOXA locus (Figure 5E), suggesting that ASXL1 is required for EZH2 occupancy and for PRC2-mediated repression of the posterior HOXA locus.

ASXL1 physically interacts with members of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) in human myeloid leukemic cells

Given that ASXL1 localizes to PRC2 target loci and ASXL1 depletion leads to loss of PRC2 occupancy and H3K27me2, we investigated whether ASXL1 might physically interact with the PRC2 complex in hematopoietic cells. Co-IP studies using an anti-FLAG antibody in HEK293T cells expressing empty vector, hASXL1-FLAG alone, or hASXL1-FLAG plus hEZH2 cDNA revealed a clear co-IP of FLAG-ASXL1 with endogenous EZH2 and with ectopically expressed EZH2 (Figure 6A). Similarly, co-IP of FLAGASXL1 revealed physical association between ASXL1 and endogenous SUZ12 in 293T cells (Figure 6A). IPs were performed in the presence of benzonase to ensure that the protein-protein interactions observed were DNA-independent (Figure 6B) (Muntean et al., 2010). We then assessed whether endogenous ASXL1 formed a complex with PRC2 members in hematopoietic cells. We performed IP for EZH2 or ASXL1 followed by Western blotting for partner proteins in SET2 and UKE1 cells, which are wildtype for ASXL1, SUZ12, EZH2, and EED. These co-IP assays all revealed a physical association between ASXL1 and EZH2 in SET2 (Figure 6B) and UKE1 cells (Figure S5). By contrast, IP of endogenous ASXL1 did not reveal evidence of protein-protein interactions between ASXL1 and BMI1 (Figure S5). Likewise, IP of BMI1 enriched for PRC1 member RING1A but failed to enrich for ASXL1, suggesting a lack of interaction between ASXL1 and the PRC1 repressive complex (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. ASXL1 interacts with the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) in hematopoietic cells.

Physical interaction between ASXL1 and EZH2 is demonstrated by transient transfection of HEK 293T cells with FLAG-hASXL1 cDNA with or without hEZH2 cDNA followed by immunoprecipitation (IP) of FLAG epitope and Western blotting for EZH2 and ASXL1 (A). HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with FLAG-hASXL1 cDNA followed by IP of FLAG epitope and Western blotting for SUZ12 and ASXL1. Endogenous interaction of ASXL1 with PRC2 members was also demonstrated by IP of endogenous EZH2 and ASXL1 followed by Western blotting of the other proteins in whole cell lysates from SET2 cells (B). Lysates from the experiment shown in Figure 6B were treated with benzonase to ensure nucleic acid free conditions in the lysates prior to IP as shown by ethidium bromide staining of an agarose gel before and after benzonase treatment. IP of endogenous EZH2 and EED in a panel of ASXL-wildtype and mutant human leukemia cells reveals a specific interaction between ASXL1 and PRC2 members in ASXL1-wildype human myeloid leukemia cells (C). In contrast, IP of the PRC1 member BMI1 failed to pulldown ASXL1. See also Figure S5.

ASXL1 loss collaborates with NRasG12D in vivo

We and others previously reported ASXL1 mutations are most common in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) and frequently co-occur with N/K-Ras mutations in CMML (Abdel-Wahab et al., 2011; Patel, 2010). We therefore investigated the effects of combined NRasG12D expression and Asxl1 loss in vivo. To do this, we expressed NRasG12D in combination with an empty vector expressing GFP alone or one of two different Asxl1 shRNA constructs in whole bone marrow cells and transplanted these cells into lethally irradiated recipient mice. We validated our ability to effectively knock down ASXL1 in vivo by performing qRT-PCR in hematopoietic cells from recipient mice (Figure 7A and Figure S6A). Consistent with our in vitro data implicating the HoxA cluster as an ASXL1 target locus, we noted a marked increase in HoxA9 and HoxA10 expression in bone marrow nucleated cells from mice expressing NRasG12D in combination with Asxl1 shRNA compared to mice expressing NRasG12D alone (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Asxl1 silencing cooperates with NRasG12D in vivo.

Retroviral bone marrow transplantation of NRasG12D with or without an shRNA for Asxl1 resulted in decreased Asxl1 mRNA expression as shown by qRT-PCR results in nucleated peripheral blood cells from transplanted mice at 14 days following transplant (A). qRT-PCR revealed an increased expression of HOXA9 and HOXA10 but not MEIS1 in the bone marrow of mice sacrificed 19 days following transplantation (B). Transplantation of bone marrow cells bearing overexpression of NRasG12D in combination with downregulation of Asxl1 led to a significant hastening of death compared to mice transplanted with NRasG12D/EV (C). Mice transplanted with NRasG12D/ASXL1 shRNA experienced increased splenomegaly (D) and hepatomegaly (E), and progressive anemia (F) compared with mice transplanted with NRasG12D + an empty vector (EV). Bone marrow cells from mice with combined NRasG12D overexpression/Asxl1 knockdown revealed increased serial replating compared with cells from NRasG12D/EV mice (G). Error bars represent standard deviation relative to control. Asterisk indicates p<0.05 (two-tailed, Mann Whitney U test). See also Figure S6.

Expression of oncogenic NRasG12D and an empty shRNA vector control led to a progressive myeloproliferative disorder as previously described (MacKenzie et al., 1999). In contrast, expression of NRasG12D in combination with validated mASXL1 knockdown vectors resulted in accelerated myeloproliferation and impaired survival compared with mice transplanted with NRasG12D/EV (median survival 0.8 months for ASXL1 shRNA vs. 3 months for control shRNA vector: p<0.005; Figure 7C) We also noted impaired survival with an independent mASXL1 shRNA construct, (p<0.01; Figure S6B) Mice transplanted with NRasG12D/Asxl1 shRNA had increased splenomegaly and hepatomegaly compared with NRasG12D/EV transplanted mice (Figure 7D and 7E and Figure S6C). Histological analysis revealed a significant increase in myeloid infiltration of the spleen and livers of mice transplanted with NRasG12D/Asxl1 shRNA (Figure S6D).

Mice transplanted with NRasG12D/Asxl1 shRNA, but not NRasG12D/EV, experienced progressive, severe anemia (Figure 7F). It has previously been identified that expression of oncogenic K/N-Ras in multiple models of human/murine hematopoietic systems results in alterations in the erythroid compartment (Braun et al., 2006; Darley et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 2003). We noted an expansion of CD71high/Ter119high erythroblasts in the bone marrow of mice transplanted with NRasG12D/Asxl1 shRNA compared with NRasG12D/EV mice (Figure S6E). We also noted increased granulocytic expansion in mice engrafted with NRasG12D/Asxl1 shRNA positive cells, as shown by the presence of increased neutrophils in the peripheral blood (Figure S6D) and the expansion of Gr1/Mac1 double-positive cells in the bone marrow by flow cytometry (Figure S6F).

Previous studies have shown that hematopoietic cells from mice expressing oncogenic Ras alleles or other mutations which activate kinase signaling pathways do not exhibit increased self-renewal in colony replating assays (Braun et al., 2004; MacKenzie et al., 1999). This is in contrast to the immortalization of hematopoietic cells in vitro seen with expression of MLL-AF9 (Somervaille and Cleary, 2006) or deletion of Tet2 (Moran-Crusio et al., 2011). Bone marrow cells from mice with combined overexpression of NRasG12D plus Asxl1 knockdown had increased serial replating (to 5 passages) compared to bone marrow cells from mice engrafted with NRasG12D/EV cells (Figure 7G). These studies demonstrate Asxl1 loss cooperates with oncogenic NRasG12D in vivo.

Discussion

The data presented here identifies that ASXL1 loss in hematopoietic cells results in reduced H3K27me3 occupancy through inhibition of PRC2 recruitment to specific oncogenic target loci. Recent studies have demonstrated that genetic alterations in the PRC2 complex occur in a spectrum of human malignancies (Bracken and Helin, 2009; Margueron and Reinberg, 2011; Sauvageau and Sauvageau, 2010). Activating mutations and overexpression of EZH2 occur most commonly in epithelial malignancies and in lymphoid malignancies (Morin et al., 2010; Varambally et al., 2002). However there is increasing genetic data implicating mutations that impair PRC2 function in the pathogenesis of myeloid malignancies. These include the loss-of-function mutations in EZH2 (Abdel-Wahab et al., 2011; Ernst et al., 2010; Nikoloski et al., 2010) and less common somatic loss-of-function mutations in SUZ12, EED, and JARID2 (Score et al., 2011) in patients with MPN, MDS, and CMML. The data from genetically-engineered mice also supports this concept with Ezh2 overexpression models revealing evidence of promotion of malignant transformation (Herrera-Merchan et al., 2012) and recent studies demonstrate a role for Ezh2 loss in leukemogenesis (Simon et al., 2012). Thus, it appears that alterations in normal PRC2 activity and/or H3K27me3 abundance in either direction may promote malignant transformation. Our data implicate ASXL1 mutations as an additional genetic alteration which lead to impaired PRC2 function in patients with myeloid malignancies. In many cases patients present with concomitant heterozygous mutations in multiple PRC2 members or in EZH2 and ASXL1; these data suggest that haploinsufficiency for multiple genes that regulate PRC2 function can cooperate in hematopoietic transformation through additive alterations in PRC2 function.

Many studies have investigated how mammalian PcG proteins are recruited to chromatin in order to repress gene transcription and specify cell fate in different tissue contexts. Recent in silico analysis suggested that ASXL proteins found in animals contain a number of domains which likely serve in the recruitment of chromatin modulators and transcriptional effectors to DNA (Aravind and Iyer, 2012). Data from ChIP and coimmunoprecipitation experiments presented here suggest a specific role for ASXL1 in epigenetic regulation of gene expression by facilitating PRC2-mediated transcriptional repression of known leukemic oncogenes. Thus ASXL1 may serve as a scaffold for recruitment of the PRC2 complex to specific loci in hematopoietic cells, as has been demonstrated for JARID2 in embryonic stem cells (Landeira et al., 2010; Pasini et al., 2010; Peng et al., 2009; Shen et al., 2009).

Recent data suggested that ASXL1 might interact with BAP1 to form a H2AK119 deubiquitanase (Scheuermann et al., 2010) however our data suggests ASXL1 loss leads to BAP1-independent alterations in chromatin state and gene expression in hematopoietic cells. These data are consonant with recent genetic studies, which have shown that germline loss of BAP1 increases susceptibility to uveal melanoma and mesothelioma (Testa et al., 2011; Wiesner et al., 2011). In contrast, germline loss of ASXL1 is seen in the developmental disorder Bohring-Opitz Syndrome (Hoischen et al., 2011), but has not to date been observed as a germline solid tumor susceptibility locus. Whether alterations in H2AK119 deubiquitanase function due to alterations in BAP1 and/or ASXL1 can contribute to leukemogenesis or to the pathogenesis of other malignancies remains to be delineated.

Integration of gene expression and chromatin state data following ASXL1 loss identified specific loci with a known role in leukemogenesis that are altered in the setting of ASXL1 mutations. These include the posterior HOXA cluster, including HOXA9, which has a known role in hematopoietic transformation. We demonstrate ASXL1 normally serves to tightly regulate HOXA gene expression in hematopoietic cells, and that loss of ASXL1 leads to disordered HOXA gene expression in vitro and in vivo. Overexpression of 5’ HOXA genes are well known proto-oncogenes in hematopoietic malignancies (Lawrence et al., 1996) and previous studies have shown that HOXA9 overexpression leads to transformation in vitro and in vivo when co-expressed with MEIS1 (Kroon et al., 1998). Interestingly, ASXL1 loss was not associated with an increase in MEIS1 expression, suggesting that transformation by ASXL1 mutations requires the co-occurrence of oncogenic disease alleles which dysregulate additional target loci. These data and our in vivo studies suggest that ASXL1 loss, in combination with co-occurring oncogenes can lead to hematopoietic transformation and increased self-renewal. Further studies in mice expressing ASXL1 shRNA or with conditional deletion of Asxl1 alone and in concert with leukemogeneic disease alleles will provide additional insight into the role of ASXL1 loss in hematopoietic stem/progenitor function and in leukemogenesis.

Given that somatic mutations in chromatin modifying enzymes (Dalgliesh et al., 2010), DNA methyltransferases (Ley et al., 2010), and in other genes implicated in epigenetic regulation occur commonly in human cancers, it will be important to use epigenomic platforms to elucidate how these disease alleles contribute to oncogenesis in different contexts. The data here demonstrate how integrated epigenetic and functional studies can be used to elucidate the function of somatic mutations in epigenetic modifiers. In addition, it is likely that many known oncogenes and tumor suppressors contribute, at least in part, to transformation through direct or indirect alterations in the epigenetic state (Dawson et al., 2009). Subsequent epigenomic studies of human malignancies will likely uncover novel routes to malignant transformation in different malignancies, and therapeutic strategies which reverse epigenetic alterations may be of specific benefit in patients with mutations in epigenetic modifiers.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture

HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and nonessential amino acids. Human leukemia cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS+1mM hydrocortisone+10% horse serum (UKE1 cells), RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS (K562, MOLM13, KCL22, KU812 cells), RPMI-1640 supplemented with 20% FBS (SET2, NOMO1, Monomac-6 cells), or IMDM + 20% FBS (KBM5 cells). For proliferation studies, 1x103 cells were seeded in 1mL volume of media in triplicate and cell number was counted manually daily for 7 days by Trypan blue exclusion.

Plasmid constructs, mutagenesis protocol, Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) and small interfering RNA (siRNA)

Primary AML patient samples and ASXL1, BAP1, EZH2, SUZ12, and EED genomic DNA sequencing analysis

Approval was obtained from the institutional review boards at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania for these studies, and informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Please see Supplemental Information for details on DNA sequence analysis.

Western Blot and Immunoprecipitation Analysis

Western blots were carried out using the following antibodies: ASXL1 (Clone N-13; Santa Cruz (sc-85283); N-terminus directed), ASXL1 (Clone 2049C2a; Santa Cruz (sc-81053); C-terminus directed), BAP1 (clone 3C11; Santa Cruz (sc-13576)), BMI1 (Abcam ab14389), EED (Abcam ab4469), EZH2 (Active Motif 39933 or Millipore 07-689), FLAG (M2 FLAG; Sigma A2220), Histone H3 lysine 27 trimethyl (Abcam ab6002), Histone H2A Antibody II (Cell Signaling Technologies 2578), Ubiquityl-Histone H2AK119 (Clone D27C4; Cell Signaling Technologies 8240), RING1A (Abcam ab32807), SUZ12 (Abcam ab12073), and total histone H3 (Abcam ab1791), and tubulin (Sigma, T9026). Antibodies different from the above used for immunoprecipitation include: ASXL1 (clone H105X; Santa Cruz (sc- 98302)), FLAG (Novus Biological Products; NBP1-06712), and EZH2 (Active Motif 39901). IP and pull-down reactions were performed in IP buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20mM Tris (pH 7.4–7.5), 5mM EDTA, 1% Triton, 100mM sodium orthovanadate, protease arrest (Genotec), 1mM PMSF, and phenylarsene oxide). To ensure nuclease-free IP conditions, IP’s were also performed using the following methodology (Muntean et al., 2010): cells were lysed in BC-300 buffer (20mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10% glycerol, 300mM KCl, 0.1% NP-40) and the cleared lysate was separated from the insoluble pellet and treated with MgCl2 to 2.5mM and benzonase (EMD) at a concentration of 1250 U/ml. The lysate was then incubated for 1–1.5 hours at 4 degrees. The reaction was then stopped with addition of 5mM EDTA. DNA digestion in confirmed on an ethidium bromide agarose gel. We then set up our IP by incubating our lysate overnight at 4 degrees.

Histone Extraction and Histone LC/MS analysis

Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells using Qiagen’s RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Valencia, CA). cDNA synthesis, labeling, hybridization and quality control were carried out as previously described (Figueroa et al., 2008). Ten micrograms of RNA was then used for generation of labeled cRNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Hybridization of the labeled cRNA fragments and washing, staining, and scanning of the arrays were carried out as per instructions of the manufacturer. Labeled cRNA from CD34+ cells treated with either ASXL1 siRNA or controls were analyzed using the Affymetrix HG-U133-Plus2.0 platform and from UKE1 cells using the Illumina Href8 array. All expression profile experiments were carried out using biological duplicates. Raw expression values from the Affymetrix platform were pre-processed using the MAS 5.0 algorithm where probeset values having "Present" calls in >=80% of samples were captured and quantile normalized across all samples on a per-chip basis. Raw expression values generated by Genome Studio (Illumina) were filtered to exclude probesets having expression values below negative background in >=80% of samples. Probesets remaining after background filtering were log-2 transformed and quantile normalized on a per-chip basis. qRT-PCR was performed on cDNA using SYBR green quantification in an ABI 7500 sequence detection system. The sequences of all qRT-PCR primers are listed in the Supplemental Information.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation and Antibodies

ChIP experiments for H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K36me3 were carried out as described previously (Bernstein et al., 2006; Mikkelsen et al., 2007). Cells were crosslinked in 1% formaldehyde, lysed and sonicated with a Branson 250 Sonifier to obtain chromatin fragments in a size range between 200 and 700 bp. Solubilized chromatin was diluted in ChIP dilution buffer (1:10) and incubated with antibody overnight at 4°C. Protein A sepharose beads (Sigma) were used to capture the antibody-chromatin complex and washed with low salt, LiCl, as well as TE (pH 8.0) wash buffers. Enriched chromatin fragments were eluted at 65°C for 10 min, subjected to crosslink reversal at 65°C for 5 hrs, and treated with Proteinase K (1 mg/ml), before being extracted by phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol, and ethanol precipitated. ChIP DNA was then quantified by QuantiT Picogreen dsDNA Assay kit (Invitrogen). ChIP experiments for ASXL1 were carried out on nuclear preps. Crosslinked cells were incubated in swelling buffer (0.1 M Tris pH 7.6, 10 mM KOAc, 15 mM MgOAc, 1% NP40), on ice for twenty minutes, passed through a 16G needle 20 times and centrifuged to collect nuclei. Isolated nuclei were then lysed, sonicated and immunoprecipitated as described above. Antibodies used for ChIP include anti-H3K4me3 (Abcam ab8580), anti-H3K27me3 (Upstate 07-449), anti-H3K36me3 (Abcam ab9050), and anti-ASXL1 (clone H105X; Santa Cruz (sc-98302)), and Ubiquityl-Histone H2AK119 (Clone D27C4; Cell Signaling Technologies 8240),

Sequencing Library Preparation, Illumina/Solexa Sequencing, and Read Alignment and Generation of Density Maps

HOXA Nanostring nCounter Gene Expression CodeSet

Direct digital mRNA analysis of HOXA cluster gene expression was performed using a Custom CodeSet including each HOXA gene (NanoString Technologies). Synthesis of the oligonucleotides was done by NanoString Technologies, and hybridization and analysis was done using the Prep Station and Digital Analyzer purchased from the company.

Animal Use, Retroviral Bone Marrow Transplantation, Flow Cytometry and Colony Assays

Animal care was in strict compliance with institutional guidelines established by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, the National Academy of Sciences Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. See Supplemental Information for more details on animal experiments.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was determined by Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher’s exact test using Prism GraphPad software; Significance of survival differences was calculated using Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Normalized expression data from CD34+ cord blood was used as a Gene Set Enrichment Analysis query of the C2 database (MSig DB) where 1,000 permutations of the genes was used to generate a null distribution. A pre-ranked gene list, containing genes up-regulated at least log2 0.5-fold where the highest ranked genes corresponds to the genes, with the largest fold-difference between Asxl1 hairpin treated UKE1 cells and those treated with empty vector was used to query the C2 MSig DB as described above.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Mutations in genes involved in modification of chromatin have recently been identified in patients with leukemias and other malignancies. Here we demonstrate a specific role for ASXL1, a putative epigenetic modifier frequently mutated in myeloid malignancies, in PRC2-mediated transcriptional repression in hematopoietic cells. ASXL1 loss-of-function mutations in myeloid malignancies result in loss of PRC2-mediated gene repression of known leukemogenic target genes. Our data provide insight into how ASXL1 mutations contribute to myeloid transformation through dysregulation of Polycomb-mediated gene silencing. This approach also demonstrates how epigenomic and functional studies can be used to elucidate the function of mutations in epigenetic modifiers in malignant transformation.

Highlights.

ASXL1 mutations are loss-of-function mutations.

ASXL1 loss results in a genome-wide reduction in H3K27me3 occupancy

ASXL1 interacts with the PRC2 complex and is important for PRC2 recruitment.

ASXL1 collaborates with co-occurring oncogenes in vivo to promote leukemogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Starr Cancer Consortium to RLL and BEB, by grants from the Gabrielle’s Angel Fund to RLL and OAW, and by a grant from the Anna Fuller Fund to RL. IA and BEB are Howard Hughes Medical Institute Early Career Scientists. AM is a Burroughs Wellcome Clinical Translational Scholar and Scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. XZ and SDN are supported by a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society SCOR award and FP by an American Italian Cancer Foundation award. OAW is an American Society of Hematology Basic Research Fellow and is supported by a grant from the NIH K08 Clinical Investigator Award (1K08CA160647-01). JPP is supported by an American Society of Hematology Trainee Research Award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Accession number: all microarray data used in this manuscript are deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under GEO accession number GSE38692. The ChIP-Seq data are deposited under GEO accession number GSE38861.

References

- Abdel-Wahab O, Pardanani A, Patel J, Wadleigh M, Lasho T, Heguy A, Beran M, Gilliland DG, Levine RL, Tefferi A. Concomitant analysis of EZH2 and ASXL1 mutations in myelofibrosis, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and blastphase myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2011;25:1200–1202. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L, Iyer LM. The HARE-HTH and associated domains: Novel modules in the coordination of epigenetic DNA and protein modifications. Cell Cycle. 2012;11 doi: 10.4161/cc.11.1.18475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejar R, Stevenson K, Abdel-Wahab O, Galili N, Nilsson B, Garcia-Manero G, Kantarjian H, Raza A, Levine RL, Neuberg D, Ebert BL. Clinical effect of point mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2496–2506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bott M, Brevet M, Taylor BS, Shimizu S, Ito T, Wang L, Creaney J, Lake RA, Zakowski MF, Reva B, et al. The nuclear deubiquitinase BAP1 is commonly inactivated by somatic mutations and 3p21.1 losses in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Nature genetics. 2011;43:668–672. doi: 10.1038/ng.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken AP, Helin K. Polycomb group proteins: navigators of lineage pathways led astray in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:773–784. doi: 10.1038/nrc2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun BS, Archard JA, Van Ziffle JA, Tuveson DA, Jacks TE, Shannon K. Somatic activation of a conditional KrasG12D allele causes ineffective erythropoiesis in vivo. Blood. 2006;108:2041–2044. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-013490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun BS, Tuveson DA, Kong N, Le DT, Kogan SC, Rozmus J, Le Beau MM, Jacks TE, Shannon KM. Somatic activation of oncogenic Kras in hematopoietic cells initiates a rapidly fatal myeloproliferative disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:597–602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307203101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YS, Kim EJ, Park UH, Sin HS, Um SJ. Additional sex comblike 1 (ASXL1), in cooperation with SRC-1, acts as a ligand-dependent coactivator for retinoic acid receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17588–17598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512616200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgliesh GL, Furge K, Greenman C, Chen L, Bignell G, Butler A, Davies H, Edkins S, Hardy C, Latimer C, et al. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature. 2010;463:360–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantuma NP, Groothuis TA, Salomons FA, Neefjes J. A dynamic ubiquitin equilibrium couples proteasomal activity to chromatin remodeling. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:19–26. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darley RL, Hoy TG, Baines P, Padua RA, Burnett AK. Mutant NRAS induces erythroid lineage dysplasia in human CD34+ cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1337–1347. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson MA, Bannister AJ, Gottgens B, Foster SD, Bartke T, Green AR, Kouzarides T. JAK2 phosphorylates histone H3Y41 and excludes HP1alpha from chromatin. Nature. 2009;461:819–822. doi: 10.1038/nature08448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst T, Chase AJ, Score J, Hidalgo-Curtis CE, Bryant C, Jones AV, Waghorn K, Zoi K, Ross FM, Reiter A, et al. Inactivating mutations of the histone methyltransferase gene EZH2 in myeloid disorders. Nat Genet. 2010;42:722–726. doi: 10.1038/ng.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa ME, Reimers M, Thompson RF, Ye K, Li Y, Selzer RR, Fridriksson J, Paietta E, Wiernik P, Green RD, et al. An integrative genomic and epigenomic approach for the study of transcriptional regulation. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CL, Lee I, Bloyer S, Bozza S, Chevalier J, Dahl A, Bodner C, Helgason CD, Hess JL, Humphries RK, Brock HW. Additional sex combs-like 1 belongs to the enhancer of trithorax and polycomb group and genetically interacts with Cbx2 in mice. Dev Biol. 2010;337:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CL, Pineault N, Brookes C, Helgason CD, Ohta H, Bodner C, Hess JL, Humphries RK, Brock HW. Loss-of-function Additional sex combslike1 mutations disrupt hematopoiesis but do not cause severe myelodysplasia or leukemia. Blood. 2009 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-230698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaebler C, Stanzl-Tschegg S, Heinze G, Holper B, Milne T, Berger G, Vecsei V. Fatigue strength of locking screws and prototypes used in smalldiameter tibial nails: a biomechanical study. J Trauma. 1999;47:379–384. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199908000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelsi-Boyer V, Trouplin V, Adelaide J, Bonansea J, Cervera N, Carbuccia N, Lagarde A, Prebet T, Nezri M, Sainty D, et al. Mutations of polycombassociated gene ASXL1 in myelodysplastic syndromes and chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:788–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbour JW, Onken MD, Roberson ED, Duan S, Cao L, Worley LA, Council ML, Matatall KA, Helms C, Bowcock AM. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas. Science. 2010;330:1410–1413. doi: 10.1126/science.1194472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Merchan A, Arranz L, Ligos JM, de Molina A, Dominguez O, Gonzalez S. Ectopic expression of the histone methyltransferase Ezh2 in haematopoietic stem cells causes myeloproliferative disease. Nat Commun. 2012;3:623. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoischen A, van Bon BW, Rodriguez-Santiago B, Gilissen C, Vissers LE, de Vries P, Janssen I, van Lier B, Hastings R, Smithson SF, et al. De novo nonsense mutations in ASXL1 cause Bohring-Opitz syndrome. Nat Genet. 2011;43:729–731. doi: 10.1038/ng.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon E, Krosl J, Thorsteinsdottir U, Baban S, Buchberg AM, Sauvageau G. Hoxa9 transforms primary bone marrow cells through specific collaboration with Meis1a but not Pbx1b. EMBO J. 1998;17:3714–3725. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar AR, Li Q, Hudson WA, Chen W, Sam T, Yao Q, Lund EA, Wu B, Kowal BJ, Kersey JH. A role for MEIS1 in MLL-fusion gene leukemia. Blood. 2009;113:1756–1758. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-163287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landeira D, Sauer S, Poot R, Dvorkina M, Mazzarella L, Jorgensen HF, Pereira CF, Leleu M, Piccolo FM, Spivakov M, et al. Jarid2 is a PRC2 component in embryonic stem cells required for multi-lineage differentiation and recruitment of PRC1 and RNA Polymerase II to developmental regulators. Nature cell biology. 2010;12:618–624. doi: 10.1038/ncb2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence HJ, Sauvageau G, Humphries RK, Largman C. The role of HOX homeobox genes in normal and leukemic hematopoiesis. Stem Cells. 1996;14:281–291. doi: 10.1002/stem.140281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SW, Cho YS, Na JM, Park UH, Kang M, Kim EJ, Um SJ. ASXL1 represses retinoic acid receptor-mediated transcription through associating with HP1 and LSD1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18–29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Ley TJ, Ding L, Walter MJ, McLellan MD, Lamprecht T, Larson DE, Kandoth C, Payton JE, Baty J, Welch J, et al. DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363:2424–2433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie KL, Dolnikov A, Millington M, Shounan Y, Symonds G. Mutant N-ras induces myeloproliferative disorders and apoptosis in bone marrow repopulated mice. Blood. 1999;93:2043–2056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margueron R, Reinberg D. The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature. 2011;469:343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature09784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzeler KH, Becker H, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, Kohlschmidt J, Mrozek K, Nicolet D, Whitman SP, Wu YZ, Schwind S, et al. ASXL1 mutations identify a high-risk subgroup of older patients with primary cytogenetically normal AML within the ELN "favorable" genetic category. Blood. 2011 doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-368225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen TS, Ku M, Jaffe DB, Issac B, Lieberman E, Giannoukos G, Alvarez P, Brockman W, Kim TK, Koche RP, et al. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature. 2007;448:553–560. doi: 10.1038/nature06008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran-Crusio K, Reavie L, Shih A, Abdel-Wahab O, Ndiaye-Lobry D, Lobry C, Figueroa ME, Vasanthakumar A, Patel J, Zhao X, et al. Tet2 loss leads to increased hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and myeloid transformation. Cancer cell. 2011;20:11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin RD, Johnson NA, Severson TM, Mungall AJ, An J, Goya R, Paul JE, Boyle M, Woolcock BW, Kuchenbauer F, et al. Somatic mutations altering EZH2 (Tyr641) in follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of germinalcenter origin. Nat Genet. 2010;42:181–185. doi: 10.1038/ng.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntean AG, Tan J, Sitwala K, Huang Y, Bronstein J, Connelly JA, Basrur V, Elenitoba-Johnson KS, Hess JL. The PAF complex synergizes with MLL fusion proteins at HOX loci to promote leukemogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:609–621. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoloski G, Langemeijer SM, Kuiper RP, Knops R, Massop M, Tonnissen ER, van der Heijden A, Scheele TN, Vandenberghe P, de Witte T, et al. Somatic mutations of the histone methyltransferase gene EZH2 in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Genet. 2010;42:665–667. doi: 10.1038/ng.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park UH, Yoon SK, Park T, Kim EJ, Um SJ. Additional sex comblike (ASXL) proteins 1 and 2 play opposite roles in adipogenesis via reciprocal regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor {gamma} J Biol Chem. 2011;286:1354–1363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.177816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasini D, Cloos PA, Walfridsson J, Olsson L, Bukowski JP, Johansen JV, Bak M, Tommerup N, Rappsilber J, Helin K. JARID2 regulates binding of the Polycomb repressive complex 2 to target genes in ES cells. Nature. 2010;464:306–310. doi: 10.1038/nature08788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel J, Abdel-Wahab O, Gonen M, Figueroa ME, Fernandez HF, Sun Z, Racevskis J, Van Vlierberghe P, Dolgalev I, Cheng J, Viale A, Socci N, Heguy A, Ketterling R, Gallagher RE, Litzow MR, Rowe JM, Ferrando AF, Paietta E, Tallman MS, Melnick AM, Levine RL. High-Throughput Mutational Profiling In AML: Mutational Analysis of the ECOG E1900 Trial (Abstract) Blood. 2010;116 [Google Scholar]

- Peng JC, Valouev A, Swigut T, Zhang J, Zhao Y, Sidow A, Wysocka J. Jarid2/Jumonji coordinates control of PRC2 enzymatic activity and target gene occupancy in pluripotent cells. Cell. 2009;139:1290–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratcorona M, Abbas S, Sanders M, Koenders J, Kavelaars F, Erpelinck-Verschueren C, Zeilemaker A, Lowenberg B, Valk P. Acquired mutations in ASXL1 in acute myeloid leukemia: prevalence and prognostic value. Haematologica. 2011 doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.051532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvageau M, Sauvageau G. Polycomb group proteins: multi-faceted regulators of somatic stem cells and cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuermann JC, de Ayala Alonso AG, Oktaba K, Ly-Hartig N, McGinty RK, Fraterman S, Wilm M, Muir TW, Muller J. Histone H2A deubiquitinase activity of the Polycomb repressive complex PR-DUB. Nature. 2010;465:243–247. doi: 10.1038/nature08966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Score J, Hidalgo-Curtis C, Jones AV, Winkelmann N, Skinner A, Ward D, Zoi K, Ernst T, Stegelmann F, Dohner K, et al. Inactivation of polycomb repressive complex 2 components in myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2011 doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-367243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Kim W, Fujiwara Y, Simon MD, Liu Y, Mysliwiec MR, Yuan GC, Lee Y, Orkin SH. Jumonji modulates polycomb activity and self-renewal versus differentiation of stem cells. Cell. 2009;139:1303–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon C, Chagraoui J, Krosl J, Gendron P, Wilhelm B, Lemieux S, Boucher G, Chagnon P, Drouin S, Lambert R, et al. A key role for EZH2 and associated genes in mouse and human adult T-cell acute leukemia. Genes Dev. 2012;26:651–656. doi: 10.1101/gad.186411.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair DA, Milne TA, Hodgson JW, Shellard J, Salinas CA, Kyba M, Randazzo F, Brock HW. The Additional sex combs gene of Drosophila encodes a chromatin protein that binds to shared and unique Polycomb group sites on polytene chromosomes. Development. 1998;125:1207–1216. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.7.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somervaille TC, Cleary ML. Identification and characterization of leukemia stem cells in murine MLL-AF9 acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda A, Goolsby C, Yaseen NR. NUP98-HOXA9 induces long-term proliferation and blocks differentiation of primary human CD34+ hematopoietic cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6628–6637. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa JR, Cheung M, Pei J, Below JE, Tan Y, Sementino E, Cox NJ, Dogan AU, Pass HI, Trusa S, et al. Germline BAP1 mutations predispose to malignant mesothelioma. Nature genetics. 2011;43:1022–1025. doi: 10.1038/ng.912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thol F, Friesen I, Damm F, Yun H, Weissinger EM, Krauter J, Wagner K, Chaturvedi A, Sharma A, Wichmann M, et al. Prognostic significance of ASXL1 mutations in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2499–2506. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varambally S, Dhanasekaran SM, Zhou M, Barrette TR, Kumar-Sinha C, Sanda MG, Ghosh D, Pienta KJ, Sewalt RG, Otte AP, et al. The polycomb group protein EZH2 is involved in progression of prostate cancer. Nature. 2002;419:624–629. doi: 10.1038/nature01075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner T, Obenauf AC, Murali R, Fried I, Griewank KG, Ulz P, Windpassinger C, Wackernagel W, Loy S, Wolf I, et al. Germline mutations in BAP1 predispose to melanocytic tumors. Nature genetics. 2011;43:1018–1021. doi: 10.1038/ng.910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Socolovsky M, Gross AW, Lodish HF. Role of Ras signaling in erythroid differentiation of mouse fetal liver cells: functional analysis by a flow cytometry-based novel culture system. Blood. 2003;102:3938–3946. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.