What's all the buzz about? Here's what to know about cicada swarms emerging this summer

After the recent winter weather, the warmth and light of summer days may be top of mind. But this summer in Missouri will not be like more recent ones — prepare for a cacophony.

This year, Missouri's largest brood of periodical cicadas, known as the "Great Southern Brood," will finally emerge after 13 years underground and result in periods of near-constant buzzing.

Get to know the insect

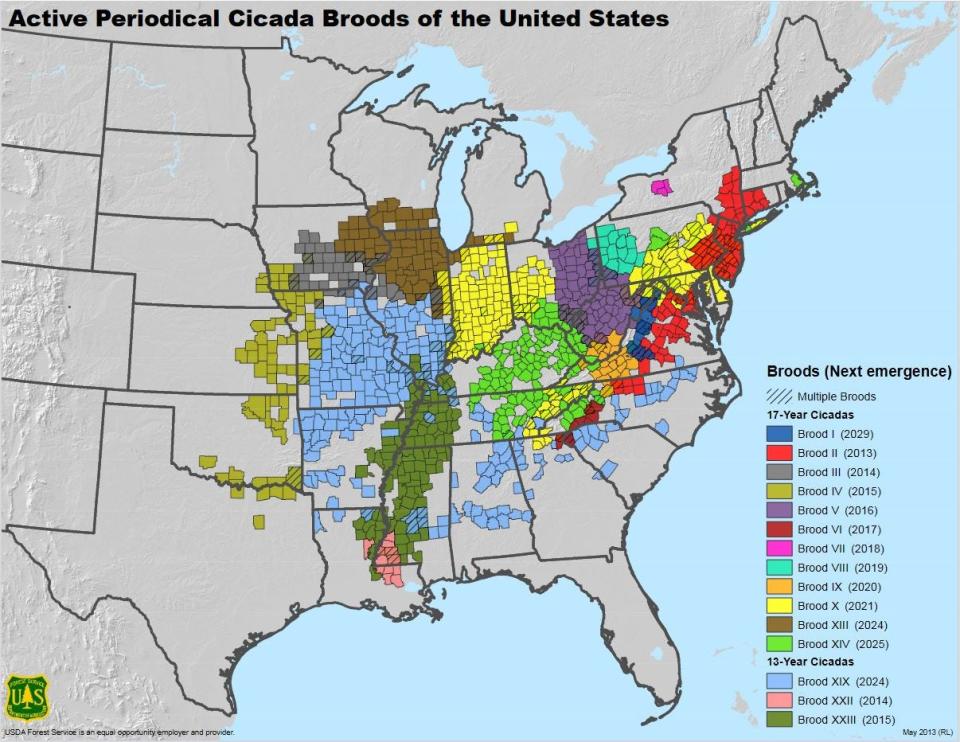

Periodical cicadas emerge in broods every 13 or 17 years. In total, there are 15 total broods of periodical cicadas that only occur in the eastern half of the United States — only four broods extend into Missouri. Periodical cicadas have a black body with orange markings and red eyes.

The brood emerging this years, Brood XIX, is a 13-year brood that stretches from southern Iowa to Oklahoma, through the southern coastal states and as far east as Washington D.C. After living in the ground, the brood will emerge in late May to mature into adults and remain above ground through June. Emergence is dependent on the warmth of the soil, which can advance or delay the event. Once the soil eight inches below ground reaches 64 degrees, the cicadas will start to emerge, roughly around the same time irises bloom.

Francis Skalicky, media specialist for the Southwest Region of the Missouri Department of Conservation, said that while being underground protects the insects from natural disasters, within 13 years the landscape above ground can change drastically and with it the habitat in which the cicada emerges into.

The swarm emergence overwhelms predators, meaning more cicadas can survive and lay eggs.

Where will they be and how will you know?

In places where the cicadas will emerge there may be thick clouds of them, Skalicky said, but the main indicator will be the sound.

"When there are a large number of them in an area, they can be very loud," he said. "This is one of nature's wonders, it really is."

At the core of the natural event is the cicadas' attempt to find mates. Emergence is part of their 13-year-long reproductive cycle, one that is longer than that of most organisms, Skalickly said.

The loud sounds associated with the presence of cicadas comes from adult males "singing" to attract females. They do so by flexing their tymbals, drum-like structures on their abdomens. Though the sound they make is large, they are relatively small themselves. An adult periodical cicada is about half the size of an adult pinky finger, according to the MDC website.

Because of their dependence on trees, cicadas will be harder to spot in less wooded areas. As cicadas shed their exoskeletons right after emerging from the ground, their "skins" can be spotted on or near tree trunks.

The current generation of cicadas will not return to the soil like their offspring will as their life cycle comes to a close. The younger cicadas themselves will burrow into the ground and emerge in another 13 years.

Concerns, importance of the insects

Periodical female cicadas lay their eggs in pencil-sized slits in tree twigs. While mature trees do not suffer significant effects, younger and smaller trees are at risk of dying but can be protected using netting with mesh smaller than 1/4 inch. Leaves on the damaged twigs will turn brown and the twigs may die.

"From the standpoint of habitat damage, this is a non-event," Skalicky said. "It's just merely an event where people can kind of sit back and say, 'Isn't nature cool?'"

Cicadas do not sting or bite and are not toxic for people or pets.

Despite these factors, cicadas help the ecosystem especially while in the ground. Their presence helps aerate and mix the soil, and their tunnels contribute to rainwater soaking into the ground. They also are a food source for birds and other organisms, and cicadas can be used as fishing bait.

When was the last, and when is the next, mass emergence?

In 2015 two broods emerged at the same time in Missouri but did not overlap geographically, with one brood bound to the very southeast region of the state and the other to the very west part. The most noticeable emergence would have been in 2011, when this same brood last emerged state-wide.

Forest Entomologist Robbie Doerhoff said there is not an official, scientific estimate of how many cicadas are expected to emerge across the entire brood. In Missouri alone, Doerhoff said it is likely that many millions of cicadas will emerge, with higher densities in areas with high tree cover.

More: New multistate cycling trail to extend through the Ozarks, connect Louisiana to Minnesota

Elsewhere in the country there has been talk of "once in 200 years" event but this will not be the case for Missouri. Brood XIX will emerge at the same time as 17-year Brood XIII, which is a rare event. But Brood XIII does not extend into Missouri and will be mainly observed in northern Illinois.

The next time a periodical cicada will swarm parts of the state will be in 2028. That event will not be as impressive as this year's, bound mostly to the southeastern portion of Missouri.

And while most Missourians will have to wait until 2037 for the next big cicada show, annual cicadas will continue to share their song toward the end of each summer.

This article originally appeared on Springfield News-Leader: Cicadas will emerge across Missouri in 2024, here's what to know