Bill Moir, chief brand and marketing officer, often recalls a story he was told about a man who simply revs his engine when he’s at a Tim Hortons drive-thru, and the employees inside know exactly who it is.

While researching the brand, I found this story referenced a half-dozen times.

So here are a couple of new stories for Moir: at a Tim Hortons in Borden, Ontario, a red pickup would drive into the lot, and before the driver, a painter who always seemed to wear a pound of paint and a giant smile, even got to the door, staff would have his large regular coffee waiting on the counter. He was in at least twice a day.

Or the one about a very proper elderly couple who would wander in after church each Sunday. Even though all the staff knew their order by heart, they would meander up to the counter and ask for tea, English breakfast (in a silver pot) with milk, two mugs and a biscuit to share. They’d sit next to a window and chat – often with the owner of the red pickup.

It’s been 10 years, and I still remember these orders, and more.

In high school, I manned the counter, sandwich bar and drive-thru at my local Tim Hortons, and can vouch that stories like Moir’s are true. In my community of about 3,000, Tims really was a hub of activity, a meeting place of the unlikeliest of minds. People knew the owner’s name. They knew the staff behind the counter. Some even brought us cookies at Christmas. It wasn’t unusual to see them three, four, even five times a day.

There wasn’t a nearby Starbucks, and boho coffee houses were non-existent, even in the nearby city of Barrie.

Competition was minimal, but that’s not why people stopped by for their morning cup of joe.

According to Johanna Faigelman, a cultural anthropologist and president of Human Branding, who has studied how coffee plays into Canadians’ lives, Tims’ success comes from a brilliant job reflecting Canadian values, which has imbued a sense of trust that few other brands have achieved.

“Many Canadians feel this connection to Tim Hortons because it has the values [humbleness, loyalty, perseverance] we do,” Faigelman says. “But a company like Starbucks – while I might drink their coffee – I feel like it’s foreign to me. It’s not who I am. It’s a bit too flashy, a bit too extreme. There’s something humble about Canadians. And there’s something humble about Tim Hortons.”

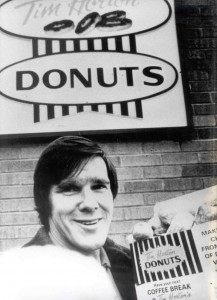

Tim Hortons was almost a steak house. The legend begins with Miles Gilbert (Tim) Horton, a defensive player for the Maple Leafs back when they stood a chance at winning the Stanley Cup.

With an annual salary hovering around $12,000, according to Douglas Hunter in his book Double Double: How Tim Hortons became a Canadian Way of Life, One Cup at a Time, Horton wasn’t pulling in nearly as much dough as his counterparts today. Nike and Gatorade weren’t signing hockey stars. Any lucrative sponsorship deal would have to be on his own terms.

And though additional revenue was a motivation, according to Hunter, Horton also just really loved the concept of owning his own restaurant.

Hence the steak house, which would have been located in Toronto in the early ’60s. Specifically, a drive-in steak house. But for reasons unknown, the resto never came to fruition, so the famous hockey player fell into another food venture shortly after – namely a burger joint that also bore his name or sometimes jersey number, which he invested in, but was owned by his brother. (After Horton’s death, it would be turned into a German food store. Horton’s brother apparently didn’t want to run the chain capitalizing on his brother’s legacy, according to Hunter.)

Hunter says there are some discrepancies in the story of how Horton came to decide on a donut shop next (and all parties who would have actually been involved in the decision – Horton, his wife and James Charade, who claimed to have had the idea in the first place – have all since died), but in 1964, Horton opened Tim Horton’s Donuts (with an apostrophe, which it would ditch in the early ’90s to comply with Quebec language laws) on Ottawa Street in Hamilton.

At the time, he was competing against 40 other chains in the city of steelworkers, and Hunter attributes early success to carrying quality products and being open 24 hours a day, drawing in the midnight shift-change at the factories.

Horton himself carried much of the advertising in the early days, mostly on in-store and POP. By tapping his hockey buddies to make guest appearances, they were able to draw in a crowd.

An early TV ad featured six donuts (including the “famous Tim Hortons Dutchie”) and the fresh coffee, but emphasized the best reason to come in was to meet the “happiest people,” featuring five very-’70s looking gentlemen leaning back from the counter, all smiles. Those guys? Horton himself, alongside fellow Leafs Pat Quinn and George Armstrong and Hamilton Tiger-Cats footballer Angelo Mosca, according to Ron Buist, the head of marketing from 1977 to 2001, in his memoir Tales from Under the Rim: The Marketing of Tim Hortons. The fifth man, Buist says, was apparently a mystery man pulled off the street, adding an air of intrigue against the familiar athletes. You never knew who you would run into at Tims.

Success and growth was a slow but natural progression, opening stores when the funds were available, with everyone involved pitching in to help bake or market the brand. Franchisees started coming on board, and the brand began to take off.

As far as marketing is concerned, much of the brand’s efforts before the ’90s weren’t particularly memorable. Moir admits he can’t even recall a single campaign created before his arrival at the brand.

Some notable shifts did occur, of course. In 1965, Ron Joyce, a former Hamilton police officer, came on board as a franchisee (and later, partner and owner), and convinced Horton to step away from using his celeb status to drive sales.

As they moved into the ’70s, focus shifted instead onto the “Always Fresh” tag and emphasis was placed on high-quality food. And when Horton died in 1974, the brand moved away from hockey-related ads, focusing its involvement with the sport on local leagues like the Timbits hockey programs.

Most marketing focused on the food, with a return to television in the early ’80s. Spots used products, not actors, allowing the brand to repurpose most assets for both French and English Canada. By the ’80s, Tims had also dropped

“Donut” from its name.

And while its TV-centric method had success (commercials usually meant a big increase in sales, Buist says, pointing to a strawberry tart campaign that caused a run on the new product, forcing the company to buy every single flat of strawberries in Newfoundland), the bulk of the brand’s growth came down to selling sought-after products, lucking out with real estate and truly understanding the commuting culture.

The ’70s through to the ’80s were a time when commuting became the norm and Canadians began to eat out en masse. According to Hunter, one Dominion Institute report conservatively estimated Canadians spent $1.2 billion on food out of the home heading into 1970. That number only climbed.

And while brands like McDonald’s, Arby’s and Harvey’s were thriving, Tim Hortons succeeded by being a niche player. It didn’t compete against the burger joints – and could indeed survive right next door – instead playing in the pure-play donut and coffee space. Competitors were only regional in nature and it wasn’t far-fetched for someone to run to McDonald’s for a burger, and then head right next door for a coffee and cruller (or, by this point, croissant or cake, new menu items introduced along the baked goods line).

Though Tim Hortons didn’t carry much of a brand identity in its early years – not compared to its uber-successful branding today – much of its success stemmed from the fact that it retained a very small-town feel, says Alan Middleton, professor of marketing at the Schulich School of Business, who has also researched the brand.

Franchisees were from the community. Employees knew the patrons. People were encouraged to loiter. And unlike a McDonald’s, which had a bit of a “big corporate chain” feel to it, Tim Hortons continued to scream “hometown.”

When the brand hired Enterprise (which later merged with sister agency JWT Canada) as its AOR in December 1989 (following a partnership with Saatchi & Saatchi Compton Hayhurst), the entire ad budget was a measly $2 million for less than 300 locations.

“We were brought in specifically to help raise Tim Hortons above the donut genre,” says Doug Poad, VP of strategic planning on Tim Hortons for JWT Canada, who has been on the account since 1990 (with a brief period away in the early 2000s). By this time, the donut and coffee space had become crowded, with brands like Dunkin’ Donuts, Coffee Time, Country Style and Robin’s Donuts all competing regionally.

The first TV spot from the agency, in 1994, featured a pair of women in a Tims with a snowstorm blowing outside, waiting and worried for a customer, unsure if he could navigate the snow. The women put on a fresh pot of coffee for him anyway. He later arrives – driving a snowplow – followed by a handful of new customers. It was the commercial that launched the jingle “You’ve always got time for Tim Hortons.”

“That still has a lot of residual awareness,” says Poad.

Go ahead, try saying it without singing it.

And this is where the brand was truly successful, integrating itself into the day-to-day of Canadians, setting the stage for its future icon status, Middleton says.

People didn’t just order coffee, they ordered Double-Doubles (since introduced as a word in the Oxford Canadian Dictionary). Donut holes were called Timbits (invented, apparently, by Layton Coulter, who was not on the marketing team at the time, but rather part of the construction department) and are on par with Kleenex and Band-Aids becoming generic names for a product, even in other donut shops in Canada. Roll up the Rim to Win, introduced in 1987, holds the status as one of the country’s most iconic contests.

This all played into the mythology of the brand, Middleton says.

Though no one spoken to for this article can really recall the early ads, everything feeling a bit “forgettable,” the brand had been ingratiated into the country’s collective consciousness, he says.

Though Tims faced competition in its first three decades, the other donut shops proved to be small potatoes compared to what was coming.

It wasn’t until Tim Hortons faced a serious challenger that it pulled ahead of the pack to become a Canadian icon, ironically coming on the heels of the brand’s purchase by American company Wendy’s in 1995, which allowed the QSR to open co-branded locations alongside the burger joint, expanding its footprint.

Starbucks had promised to enter the market, bringing with it the perception of higher quality coffee. Despite having never tasted a cup, in 1995, 20% of Canadians believed Starbucks had superior brew compared to Tim Hortons, says Poad.

Alongside efforts to break into new day-parts with the introduction of bagels in ’96, followed by sandwiches and soups a few years later, Tims needed to refocus its marketing efforts on its bread-and-butter item: coffee. But how do you galvanize people to buy a product they can make in their own home?

“We’d done a lot of research around Canadian values – what Canadians find important,” he says. “Things like personal friendships, loyalty and perseverance.” Our greatest heroes were not the larger-than-life athletes or superstars, like our American counterparts, the Tims researchers learned. It was our parents, who had “made something of themselves,” Poad says.

Culling through information from focus groups, they stumbled across the story of Lillian, a little old lady who lived in Nova Scotia, who would trek up and down a steep hill each day so she could enjoy a cup of coffee at Tims. And they used the actual Lillian in the spot – making it a documentary of sorts, launched in 1996. Thus the Tims “True Stories” were born. What would follow included ads about “Sammy,” the dog who would bring his owner a cup of coffee, or a group of horseback riders out in Squamish B.C., who were such frequent Tims visitors, the store owner put a hitching post outside.

These are the most memorable and effective commercials the brand has made, Middleton says. Just look at the lengths people would go to get a cup of Tims – it must be a superb experience.

The secret to the brand’s success was that the spots represented attributes held dear to Canadians, says Paul Wales, EVP and ECD at JWT, who has worked on Tim Hortons since 1999. Lillian was all about perseverance; Sammy, about friendship.

Canadians, Poad says, were becoming a more prideful people – finding their own identity and finding honour in their nationality, and campaigns began to reflect that – with tales of expats recreating Canadianess in their homes away from home (including the requisite cup of Tims) or Tims travel mugs worn as a badge of honour while travelling abroad.

And towards the mid-2000s, it became less about the lengths people would go to get a cup of coffee, but rather the role Tims played in Canadians’ lives.

New spots focused on how a cup of coffee helped bridge a generational gap (“Proud Fathers,” showing an immigrant dad who reconnects with his son over a cup of coffee at the grandson’s hockey practice), or how a cup of coffee could welcome new immigrants to Canada (“Welcome Home,” featuring another immigrant father gathering supplies for his incoming family, unfamiliar with Canadian winters), tugging at heartstrings.

New spots focused on how a cup of coffee helped bridge a generational gap (“Proud Fathers,” showing an immigrant dad who reconnects with his son over a cup of coffee at the grandson’s hockey practice), or how a cup of coffee could welcome new immigrants to Canada (“Welcome Home,” featuring another immigrant father gathering supplies for his incoming family, unfamiliar with Canadian winters), tugging at heartstrings.

The brand grew immensely during this time, benefiting from the new Wendy’s ownership, as well as a more robust 52-weeks-a-year media buy (today handled by Mindshare) focused on new product offerings. But the Tims “True Stories” are what elevated the brand, making it something relatable to Canadians, Middleton says. What’s more, the characters looked like people you might pass on the street, he adds. “Everyone” was Tim Hortons’ target, so Tims targeted everyone.

“People in the commercials have never been heroes, always people like me. People related to [Tims ‘True Stories’] because it was an evocation of their relationship with the community,” Middleton says. “It was the way we wanted our lives to be.”

Cultural sociologist Patricia Cormack, professor at St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia, says these spots were so successful, they have become part of Canadians’ self-image.

In other words, Tims got us because Tims was us.

The ’00s could be considered the golden years for the chain, quietly pulling ahead of McDonald’s as the most successful and profitable Canadian QSR. The brand opened its 2,000th location in 2000, politicians began actively seeking out the “Tim Hortons” voter, making frequent pit stops on campaign trails at nearby shops. Prime Minister Stephen Harper held a special event honouring the repatriation of Tim Hortons when it split from Wendy’s in 2009 for tax purposes. The Royal Canadian Mint chose the restaurant to be the exclusive distribution partner for special commemorative poppy coins, and here at strategy, we named it one of our Brands of the Decade.

But once you’re on top, where can you go?

From 2010 onwards, there was a sea change in the QSR space. Starbucks – with its higher price point – wasn’t the main competition anymore.

The peaceful coexistence of the niche donut shop and nearby burger joints was over. With much richer lunchtime and breakfast offerings, McDonald’s and Subway were the new entrants. In 2008, McDonald’s began making an aggressive play for the breakfast segment – and to win at breakfast you need to win at coffee, Middleton says – launching McCafé, hoping to entice Canadian coffee drinkers away from Tims. It began actively promoting with free coffee giveaways, coinciding with Tim Hortons’ very successful (and still dominating) Roll up the Rim promotion.

And it had some success. Though Tim Hortons still maintains a 70-to-80% share (depending on the source) of the coffee market, by its own count McDonald’s estimates its coffee share has jumped to 10.3%, doubling in four years.

At the same time, the new millennial and gen Z demos were growing up, and they weren’t as enamoured with the brand as their predecessors, preferring to go for wraps (a market both McDonald’s and Subway compete in), or local, non-chain options, says Middleton.

Tims’ same-store sales have slowed over the past few years and it’s had a very public defeat in its attempts to enter certain U.S. markets. Sales growth has hinged on its footprint growing, but the brand has nearly reached capacity, blanketing the Canadian landscape with the brown and red locales. A 2009 partnership with Cold Stone Creamery, rolling out 100 branded locations of the ice cream parlour within Tim Hortons across Canada, flopped, falling victim to Canada’s long, cold winters.

To combat the decline, the QSR has started quietly renovating its locations with plush chairs, exposed bricks and Wi-Fi, encouraging people to once again sit for a while. TimsTV is being rolled out across the country to offer a proprietary entertainment network, and a new loyalty program and co-branded credit card with CIBC launched in February 2014, designed to encourage more frequent visits (offering 1% cash back redeemable at Tim Hortons).

New foods have been slowly introduced, including panini sandwiches, wraps and dark roast coffee.

The brand has also shuttered a number of its underperforming U.S. locations and has stepped away from the partnership with Cold Stone Creamery.

And while the brand has moved away from the quiet, unassuming approach evident in the early “True Stories” years, that may actually be best for the brand, reflecting the new Canadian mentality.

According to internal research, Tim Hortons has found Canadians are a more prideful, celebratory people who aren’t afraid to boast a bit. (Faigelman agrees based on her own research, noting the change among Canadians in their cultural habits.) As a result, there’s been a shift in marketing efforts to be a bit bigger, bolder, and yes, celebratory.

“Jump the Boards,” for example, features hockey prodigy Sidney Crosby and a stadium full of people taking to the ice to compete, declaring hockey is “our game,” in advance of the Sochi 2014 Olympics.

The brand has also been active in the digital space, working with digital AOR OgilvyOne. And Tims is jumping on opportunities to align itself with other Canadian icons on social media, such as a creating a special donut-Timbit concoction for Jason Priestley after his appearance on How I Met Your Mother, a special mug of Ryan Gosling’s mug, or a Deadmau5-inspired treat.

The brand has also been active in the digital space, working with digital AOR OgilvyOne. And Tims is jumping on opportunities to align itself with other Canadian icons on social media, such as a creating a special donut-Timbit concoction for Jason Priestley after his appearance on How I Met Your Mother, a special mug of Ryan Gosling’s mug, or a Deadmau5-inspired treat.

It’s the approach the brand took for its 50th anniversary campaign as well, which features three friends walking through the decades, reminiscing about past cups of coffee. It’s not the heartstrings-tugging ad of say “Proud Father” or “Welcome Home,” or the true story of “Lillian.” It pokes fun at the past five decades with overemphasized cultural icons in a whimsical way, but it’s something Canadians want to see, says Glenn Hollis, VP brand strategy, marketing, digital and experience at Tim Hortons. It’s geared at the loyal fans, he says, those who grew up with the brand. The anniversary campaign also features special packaging from design firm Pigeon.

“[Tim Hortons] evolved with us,” says Middleton of the brand’s continued success. “It evolved from coffee and donuts, gradually over the years into different day-parts. It started very modestly.” Much like Canadians.

And it’s that slow-building embodiment of consumers’ values that has given us the sense of trust in the brand, says Faigelman, and one of the reasons we flock to it for our morning cup of joe, afternoon donut or evening sandwich. “The entire brand identity has been humanized into standing for ‘being Canadian,'” she adds. “And that’s a really formidable task.”

As Canadians shifted from small-town roots to suburban car culture to a more boastful nation, the brand ingratiated itself into our collective conscious. It wasn’t for us, it was of us, and that’s perhaps been its greatest marketing tool to date.

Walk through memory lane with these iconic Tim Horton’s ads.