By Julian French.

The Battle of the Somme

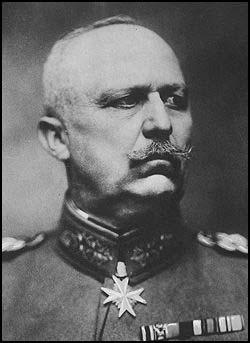

“The English generals are wanting in strategy. We should have no chance if they possessed as much science as their officers and men had of courage and bravery. They are lions led by donkeys”.

General Erich Ludendorff.

1 July, 2016. Zero Hour One Hundred Years plus Two. It was the bloodiest day ever for the British Army. A century ago some 300 kilometres/190 miles to the south of me the “big push” was underway. Twenty-nine British Army divisions were advancing across no man’s land in the face of heavy machine gun, mortar, infantry and artillery fire laid down by seven defending German divisions across a 50 km/30 mile front. By Zero plus Five the British had taken some 55,000 casualties, of whom 20,000 were dead.

The reason for the Battle of the Somme was the Battle of Verdun. By 1 July, 1916 the French Army had already been fighting on the charnel fields of Verdun for 134 days. German commander General Erich von Falkenhayn reportedly said his aim at Verdun was to bleed France white. Between February and December 2016 the French Army would suffer up to 540,000 casualties, of whom some 150,000 would be killed.

The French commander-in-chief Marshal Joffre pleaded with the British to launch a major offensive in the west to ease the pressure on French lines at Verdun. Crucially, British commander-in-chief General Sir Douglas Haig believed German forces had suffered sufficient attrition at Verdun to believe a combined Anglo-French assault on the German lines would succeed. Haig even believed it might be possible to enact a complete breakthrough of German defences and commence a rout. The Somme area was chosen for the offensive because it was where British and French forces stood alongside each other.

Five days prior to the offensive the British started an enormous artillery barrage that saw over one million shells fired at the German defences right up until the commencement of the advance. The fact that such a barrage could be mounted was proof the British had overcome the crippling shortage of artillery shells from which the British Army had suffered since the outbreak of war in August 1914.

The British offensive should have succeeded, at least on paper. British forces enjoyed more than a three-to-one superiority in men and materiel. However, the offensive failed. The reasons for failure are manifold. However, in the intervening century the myth of the Somme has become overpowering and made it hard to discern fact from fiction.

The British Army at the Somme included in its ranks a significant number of Kitchener’s New Army. This was a newly-formed, ‘green’ (inexperienced) ‘citizen army’, which included the Sheffield City Battalion, from my own home town, and which fought with distinction on 1 July at Serre. However, there were also a large number of battle-hardened British, Australian, Canadian, New Zealand and other forces committed to the Somme offensive.

Marshal Joffre had promised the British that the French force on Haig’s right flank would be equal in size to that that of the British. However, by late June the French Army was simply unable to put such a force into the line such was the pressure being exerted on them by Falkenhayn at Verdun.

However, it was not green pal’s battalions or the French that did for Haig’s Somme offensive. It was Haig himself who doomed the Somme offensive to failure through bad strategy and over confidence. By committing to a front some 30 km/50 miles wide the British force was spread far too thinly. The artillery barrage whilst impressive did nothing like the damage expected to the well-engineered German trenches and forewarned the enemy as to the scale and location of the offensive. Cohesion between the British divisions, and communications between high command and operational commanders was via a rudimentary command chain that was unable to withstand the confusion of a dynamic offensive after so long having been committed to a relatively static defence.

By November 18, 1916, when Haig called off the offensive, the British had gained an area some 12 km/9 miles deep and some 25 km/20 miles wide, but had suffered 623,907 casualties at a rate of some 3000 casualties per day. However, German losses also numbered 465,000 casualties. Conscious that the German Army could not suffer such losses again over the winter of 1916/1917 the Germans engineered the fearsome Hindenburg line behind the Somme battlefield to which they retreated in February 2017. Crucially, the Somme offensive did indeed help relieve pressure on the French Army at Verdun.

Lessons were learned from the failed Somme offensive. In March 1918 Ludendorff launched Operation Michael, a last desperate attempt by the German High Command to split British and French forces which were being reinforced daily by the arrival of US forces. German Stormtroopers were unleashed across what had been the old Somme battlefield. At first the British reeled back but crucially did not break.

At the Battle of Amiens, which commenced on 8 August, 1918, on what Ludendorff called the “black day of the German Army”, an exhausted German force faced a new new All Arms assault by the British. Out of the mist an enormous artillery barrage was unleashed, but this time British, Australian, Canadian, Indian and New Zealand forces, supported by American and French forces, and all under a ‘supreme’ unified command, advanced right behind the barrage employing new flexible ‘grab and hold’ infantry tactics. The force was also supported by a large number of tanks and massive air power.

Crucially, the assault took place over a much narrower front than the Somme offensive enabling the British force to punch through German lines. The German Army true to its tradition fought bravely but as an offensive force it was broken at Amiens. German commanders of a later generation studied the All Arms Battle very closely, but they gave it another name – Blitzkrieg!

(1)

In memory of all the fallen on all sides at the Battle of the Somme which began one hundred years ago today.