The regular arrangements of β-strands around a central axis in β-barrels and of α-helices in coiled coils contrasts with the irregular tertiary structures of most globular proteins, and have fascinated structural biologists since they were first discovered. Simple parametric models have been used to design a wide range of α-helical coiled coil structures, but to date there has been no success with β-barrels. Here we first show that accurate de novo design of β-barrels requires considerable symmetry breaking to achieve continuous hydrogen bond connectivity and eliminate backbone strain. We then build ensembles of β-barrel backbone structures with cavity shapes matched to the fluorogenic compound DFHBI, and use a hierarchical grid-based search method to simultaneously optimize the rigid body placement of DFHBI in these cavities and the identities of the surrounding amino acids for high shape and chemically complementary binding. The designs have high structural accuracy and bind and fluorescently activate DFHBI in vitro and in E. coli, yeast and mammalian cells. This de novo design of small molecule binding activity, using backbones custom built to bind the ligand, sets the stage for design of increasingly sophisticated ligand binding proteins, sensors, and catalysts not limited by the backbone geometries available in known protein structures.

There have been considerable recent advances in designing protein folds from scratch1,2, as well as redesigning already existing native scaffolds to bind small molecules3–5, but two outstanding unsolved challenges remain. The first is the de novo design of all-β proteins, which is complicated by the tendency of β-strands and sheets to associate intermolecularly to form amyloid like structures if their register is not perfectly controlled6. The second is the design of protein backbones customized to bind small molecules of interest, which requires precise control over both backbone and sidechain geometry5, as well as balancing the often opposing requirements of protein folding and function7. Success in developing such methods would reduce the longstanding dependency on natural proteins by enabling protein engineers to craft new proteins optimized to bind chosen small-molecule targets, and lay a foundation for de novo design of proteins customized to catalyze specific chemical reactions.

Principles for designing β-barrels

β-barrels are single β-sheets that twist to form a closed structure in which the first strand is hydrogen bonded to the last8. Anti-parallel β-barrels are excellent scaffolds for ligand binding, as the base of the barrel can accommodate a hydrophobic core to provide overall stability, and the top of the barrel can provide a recessed cavity for ligand binding9, often flanked by loops that can contribute further binding affinity and selectivity10. However β-sheet topologies are notoriously difficult to design from scratch, with no reported success to date, although several descriptive parametric models of β-barrels have been proposed11–13. We first set out to address this challenge by parametrically generating regular arrangements of 8 anti-parallel β-strands using the equations for an elliptic hyperboloid of revolution (adapted from14, Extended Data Fig. 1a). β-barrels are characterized by their shear number ‘S’ — the total shift in strand registry between the first and last strand — which determines the hydrophobic packing arrangement and the diameter of the barrel (Supplementary Methods)15,16. We selected a shear number of S=10 because it is difficult to achieve good core packing for S=8 (the barrel has a smaller diameter and the Cα-Cβ vectors point directly at each other), and S=12 results in a cavity too large to fill with sidechains (Extended Data Fig. 1b–d). We generated ensembles of hyperboloids by sampling the elliptical parameters and the tilt of the generating lines with respect to the central axis around ideal values computed for S=10, and then placed Cαs on the hyperboloid surface (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Methods). As found in earlier simulation work17, backbones generated with constant angles between strands could not achieve perfectly regular hydrogen bonding. To resolve this problem, we introduced force-field guided variation in local twist by gradient based minimization. We selected the backbones with the most extensive inter-strand hydrogen bonding, connected the strands with short loops and carried out combinatorial sequence optimization to obtain low energy sequences. Synthetic genes encoding 41 such designs were produced and the proteins expressed in E. coli. Almost all were found to be insoluble or oligomeric; none of this first set of 41 designs were monomeric with an all-β circular dichroism spectrum (Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 1: Principles for designing β-barrels.

(a and b) Two methods for β-barrel backbone generation. a, Parametric generation of 3D backbones based on the hyperboloid model. The cross-section of the barrel is controlled on the global level with parameters (r, rA and rB). b, Specification of residue connectivity in a 2D map followed by assembly of 3D backbones with Rosetta. The cross-section geometry is controlled on the local level with torsion angle bins specified for each residue. c, Incorporation of glycine kinks and β-bulges reduces Lennard Jones repulsive interactions in β-barrels. Full backbones are shown on the left and one Cβ-strip is shown on the right. (Top) No β-bulge, no glycine kink; (Middle) one glycine kink in the middle of each Cβ-strip, no β-bulge; (Bottom) one glycine kink in the middle of each Cβ-strip, and β-bulges placed near the β-turns. d, Blueprint used to generate a β-barrel of type (n=8;S=10) with a square cross-section suitable for ligand binding. The values of the barrel radius (r) and tilt of the strands (θ) used to place glycines are determined by the choice of n and S. The residues in the 2D blueprint (left) and the 3D structure (middle) are colored by backbone torsion bins (right, Rosetta’s ABEGO types nomenclature). Shaded and open circles represent residues facing the barrel interior and exterior, respectively. Glycine positions are shown as yellow circles and β-bulges as stars. The “corners” in the β-sheet resulting from the presence of glycine kinks are shown as vertical dashed lines. C: barrel circumference; D: distance between strands.

In considering the possible reasons for the failure of the initial designs, we noted that many of the backbone hydrogen bond interactions on the top and bottom of the barrels were distorted or broken (Extended Data Fig. 1e,f). To investigate the origins of this distortion, we experimented with three alternative approaches to generating uniform β-barrel backbones lacking loops and with valine at every position as a place-holder (Supplementary Methods). In all cases, we observed breaking of hydrogen bond interactions following structure minimization with Rosetta relaxation protocol (Extended Data Fig. 2a), suggesting there is strain inherent to the closing of the curved β-sheet on itself. To identify the origin of this strain, we repeated the relaxation after imposing strong constraints on the hydrogen bond interactions to prevent them from breaking. As illustrated in Fig. 1c, the strain manifested in two places. First, steric clashes build up along strips of side-chains in the directions of the hydrogen bonds, perpendicularly to the direction of the β-strands (“Cβ-strips”, Fig.1c). Second, a number of residues acquired unfavorable left handed twist (Extended Data Fig. 2b,c; the chirality of the peptide backbone favors right handed twist). To reduce the strain arising from steric clashes between Cβ atoms, and from the local left handed twist, we replaced the central valine residue of each Cβ-strip with a glycine (which are normally disfavored in β-sheets18). The achiral glycine can have a left-hand twist without disrupting the β-sheet hydrogen bond pattern15,19 and lacks a Cβ atom, reducing the steric clashes within Cβ-strips (Fig. 1c, middle). The backbones of most of these glycine residues shifted to the positive Φ torsion bin after minimization to form torsional irregularities in the β-sheet (“glycine kinks”15, Extended Data Fig. 2d–e).

Based on these observations, we hypothesized that large local deviations in ideal β-strand twist are necessary to maintain continuous hydrogen bond interactions between strands in a closed β-barrel, and hence that a parametric approach assuming uniform geometry was not well suited to building such structures. Therefore, we chose to build β-barrel backbones starting from a 2D map specifying the peptide bonds, the backbone torsion angle bins20, and the backbone hydrogen bonds (Fig. 1b). In contrast to parametric backbone design, which may be viewed as “3D to 2D” approach as a 3D surface is generated and then populated with residues, this alternative strategy proceeds from 2D to 3D and can readily incorporate local torsional deviation. We generated 3D protein backbones using Rosetta Monte Carlo structure generation calculations starting from an extended peptide chain21, guided by torsional and distance constraints from the 2D map.

We found that we could control the volume and the 3D shape of the β-barrel cavity by altering the placement of glycine kinks in the 2D map. Such kinks dramatically increase local β-sheet curvature, forming corners in an otherwise roughly circular cross-section (Extended Data Fig. 2f,g). We chose to design a square barrel shape and created four corners in the β-sheet by placing five glycine kinks to un-strain the five Cβ-strips and one glycine kink to correct the twist of the longest hairpin (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Methods & Extended Data Fig. 3a). With this choice, the resulting 3D backbones have a large interior volume suitable for a ligand-binding cavity. When such backbones were built with canonical type I’ β-turns connecting each β-hairpin, we observed steric strain at the extremities of the Cβ-strips (Fig. 1c, bottom) and disruption of hydrogen bond interactions following structure relaxation (Extended Data Fig. 3e). This likely arises because the considerable curvature at the glycine kinks requires that the β-hairpins paired with it (dashed vertical line in Extended Data Fig. 3b) must have greater right handed twist than can be achieved with canonical β-hairpins. We reasoned that accentuated right-handed twist could be achieved by incorporating β-bulges — disruptions of the regular hydrogen bonding pattern of a β-sheet2,22,23. Indeed, we found that strategic placement of β-bulges on the bottom of the barrel (defined as the side of the N- and C- termini) and bulge-containing β-turns22 on the top of the barrel eliminated steric strain and stabilized the hydrogen bonds between the β-strand residues flanking the turns (Extended Data Fig. 3e,f). To tie together the bottom of the barrel, we introduced a “tryptophan corner”24,25 by placing a short 3–10 helix followed by a glycine kink and a Trp at the beginning of the barrel, and an interacting Arg at the C-terminus (Extended Data Fig. 3g–j).

500 backbones were generated from the 2D map incorporating the above features (see Methods), and Rosetta flexible backbone sequence design calculations were carried out to identify low energy sequences for each backbone. Four designs with low energy and backbone hydrogen bonding throughout the barrel were selected for experimental characterization (Extended Data Fig. 4a). The sequences of these designs are not related to those of known native proteins with BLAST E-values > 0.1, and fold into the designed structure in silico (Fig. 2a). Synthetic genes encoding the designs were expressed in E. coli. Three of the designs were expressed in the soluble fraction and purified; two had characteristic β-sheet far-UV circular dichroism (CD) signal (Fig. 2; Extended Data Fig. 4b). Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) coupled with multi-angle light scattering (MALS) showed that one was a stable monomer (BB1) and the other (BB2) a soluble tetramer (Extended Data Fig. 4c).

Figure 2: Folding, stability and structure of design BB1.

a, In silico folding energy landscape. Each grey dot indicates the result of an independent ab initio folding calculation; black dots show results of refinement trajectories starting from design model and dark grey dots from lowest energy ab initio models. b, Size-exclusion chromatogram of the purified monomer (14 kD). c, Far-UV CD spectra at 25°C (grey line), 95°C (black dashed line) and cooled back to 25°C (black dotted line). d, Near-UV CD spectra in Tris buffer (grey line) and 7M GuHCl (black line). e, Cooperative unfolding in GuHCl monitored by near-UV CD signal at 285 nm (grey line) and tryptophan fluorescence (black line). f-j, Superpositions of the crystal structure (grey) and the design model (pink): overall backbone superposition(f); section along the β-barrel axis showing the rotameric states of core residues(g); one of the top loop with a G1 β-bulge(h); and equatorial cross-section of the β-barrel, showing the geometry of the interior volume (i) . The glycine kinks are shown as sticks. The bottom of the panel shows the cross-section of the three closest native β-barrel structures based on TM-score33 (PDB IDs: 1JMX (0.77); 4IL6(chain O) (0.73); 1PBY (0.71)). (j) One of the bottom loops with a classic β-bulge. (k) Crystal structure and 2mFo − DFc electron density of the tryptophan corner, contoured at 1.5σ.

BB1 exhibited a strong near-UV signature suggesting an organized tertiary structure (Fig. 2d). The design was stable at 95°C, and cooperatively unfolded in guanidine denaturation experiments (Fig. 2e). The crystal structure of BB1 solved at 1.6Å resolution was very close to the design model (1.4Å backbone RMSD over 99 of 109 residues; Extended Data Fig. 4d–f). Essentially all of the key features of the design model are found in the crystal structure (Fig. 2f–k). The barrel cross-section in the crystal structure is very similar to that of the design model, with an overall square shape with corners at the glycine kinks. Natural β-barrel crystal structures do not have this shape; the cross section of the closest structure match in the PDB is shown in Fig. 2i. All 7 designed β-turns and β-bulges are correctly recapitulated in the crystal structure (Fig. 2h, j), along with the 3–10 helix and tryptophan corner (Fig. 2k).

Design of small-molecule binding β-barrels

Having determined principles for de novo design of β-barrels, we next sought to design functional β-barrels with binding sites tailored for a small molecule of interest. We chose DFHBI (Fig.3a, left, green), a derivative of the intrinsic chromophore of GFP, to test the computational design methods. Due to its internal torsional flexibility in solution, DFHBI does not fluoresce unless it is constrained in the planar Z conformation26,27. We sought to design protein sequences that fold into a stable β-barrel structure with a recessed cavity lined with side-chains to constrain DFHBI in its fluorescent planar conformation. We chose to take a three step approach: (1) de novo construction of β-barrel backbones, (2) placement of DFHBI in a dedicated pocket, and (3) energy-based sequence design. For the first step, we stochastically generated 200 β-barrel backbones based on the 2D map described above (Extended Data Fig. 5b–d).

Figure 3: Computational design and structural validation of β-barrels with recessed cavities for ligand binding.

a, (Left) Ensembles of side chains generated by the RIF docking method making hydrogen bonding (upper left) and hydrophobic interactions (lower left) with DFHBI (green); pre-generated interacting rotamers are shown in grey with backbone Cα highlighted by magenta spheres. (Right) Ensemble of 200 β-barrel backbones, with Cα atoms surrounding the binding cleft indicated by magenta spheres. b, Each ligand/scaffold pair (left) with multiple ligand-coordinating interactions from RIF docking is subjected to Rosetta energy-based sequence design calculations (right): positions around the ligand (light purple, above the dashed line) are optimized for ligand binding; the bottom of the barrel (dark grey, below the dashed line), for protein stability. c, (Left) Crystal structure (cyan cartoon with grey surface) of b10 with a recessed binding pocket filled with water molecules (red spheres). (Middle) b10 design model backbone (silver) superimposed on the crystal structure (cyan). (Right) Comparison of crystal structure and design model for two different barrel cross sections (indicated by dashed lines); glycine Cα atoms are indicated by spheres in the upper layer.

The placement of ligand in the binding pocket requires sampling of both the rigid body degrees of freedom of the ligand, and the sequence identities of the surrounding amino acids that form the binding site. Because of the dual challenges associated with optimization of structure and sequence simultaneously, most approaches to designing ligand-binding site to date have separated sampling into two steps: rigid body placement of the target ligand in the protein binding pocket followed by design of the surrounding sequence4,5,28. This two-step approach has the limitation that optimal rigid body placement cannot be determined independently of knowledge of the possible interactions with the surrounding amino acids. The RosettaMatch method29 can identify rigid body and interacting residue placements simultaneously, but is limited to a small number of pre-defined ligand interacting residues3. We addressed these challenges with a new “Rotamer Interaction Field (RIF)” docking method that simultaneously samples over rigid body and sequence degrees of freedom. RIF docking first generates an ensemble of billions of discrete amino acid side chains that make hydrogen-bonding and non-polar hydrophobic interactions with the target ligand (Fig. 3a, right). Then, scaffolds are docked into this pre-generated interacting ensemble using a grid-based hierarchical search algorithm (Extended Data Fig. 5a). We used RIF docking to place DFHBI into the upper half of the β-barrel scaffolds, resulting in 2,102 different ligand/scaffold pairs with at least four hydrogen bonding and two hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 3a).

To identify protein sequences that not only buttress the ligand-coordinating residues from the RIF docking but also have low intra-protein energies to drive protein folding, we developed and applied a Monte Carlo-based sequence design protocol that iterates between 1) fixed-backbone design around the ligand-binding site to optimize ligand interacting energy and 2) flexible-backbone design for the rest of protein optimizing the total complex energy (Fig. 3b). Forty-two designs with large computed folding energy gaps and low energy intra-protein and protein-ligand interactions were selected for experimental characterization, plus an additional 14 disulfide bonded variants (Extended Data Fig. 5e). Ligand docking simulations following extensive structure refinement revealed that due to the approximate symmetry of the hydrogen bonding pattern of DFHBI, many of the designed binding pockets could accommodate the ligand in two equally-favorable orientations (Extended Data Fig. 5f).

Synthetic genes encoding the 56 designs were obtained and the proteins expressed in E. coli. Thirty-eight of the proteins were well expressed and soluble; SEC and far-UV CD spectroscopy showed that 20 were monomeric β-sheet proteins (Supplementary Table 3). Four of the oligomer-forming designs became monomeric upon incorporation of a disulfide bond between the N-terminal 3–10 helix and the barrel β-strands. The crystal structure of one of the monomeric designs (b10) was solved to 2.1Å, and was found to be very close to the design model (0.57Å backbone RMSD, Fig. 3c). The upper barrel of the crystal structure maintains the designed pocket, which is filled with multiple water molecules (Fig. 3c, & Extended Data Fig. 6b). Thus, the design principles described above are sufficiently robust to allow the accurate design of potential small molecule binding pockets.

Two of the 20 monomeric designs — b11 and b32 — were found to activate DFHBI fluorescence by 12- and 8- fold with binding dissociation constants (KD) values of 12.8 and 49.8 μM, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 6f). Knockout of interacting residues in the designed binding pocket eliminated fluorescence (Extended Data Fig. 6g). The ligand-binding activity comes at a substantial stability cost as almost half of the barrel is carved out to form the binding site: while the nonfunctional BB1 design does not temperature denature, both b11 and b32 undergo reversible thermal melting transitions (Extended Data Fig. 6e). b11 contains a disulfide bond while the parent design lacking the disulfide (b38) is not a monomer (Extended Data Fig. 6c,d). We sought to improve the binding interactions by redesigning β-turns around the ligand binding site (Supplementary Table 6). b11L5F with a 5-residue fifth turn activated DFHBI fluorescence by 18-fold with a KD value of 7.5 μM (Extended Data Fig. 6f, h).

The sequence determinants of b11L5F fold and function were investigated by assaying the effect of each single amino acid substitution (19*110 = 2,090 in total) on both protein stability30 and DFHBI activation on the yeast cell surface. The function (fluorescence activation) and stability (proteolysis resistance) landscapes have similar overall features consistent with the design model, with residues buried in the designed β-barrel geometry much more conserved than surface exposed residues (Fig. 4a & Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). The function landscape suggests the geometry of the designed cavity is critical to activating DFHBI fluorescence: the key sequence features that specify the geometry of the cavity - the glycine kinks and the tryptophan corner - are strictly conserved (Fig. 4a). Among the seven coordinating residues from RIF docking, only a single substitution (V103L) increased fluorescence (Fig. 4c, upper panel). Whereas the structure and function landscapes were very similar at the bottom of the barrel (Fig. 4b), there was a striking trade-off between stability and function at the top of the barrel around the designed binding site (Fig. 4c): many substitutions that stabilize the protein drastically reduce fluorescence activation (Fig. 4c, right). This bottom/top contrast indicates that success in de novo design of fold and function requires a substantial portion of the protein (in our case, the bottom of the barrel) to provide the driving force for folding as the functional site will likely be destabilizing.

Figure 4: Sequence dependence of fold and function.

Each position was mutated one at a time to each of the other 19 amino acids, and the resulting library subjected to selection for fluorescence or stability to proteases. a, (Upper) b11L5F backbone model colored by relative fluorescence activation score at each position. Blue positions are strongly conserved during yeast selection; red positions are frequently substituted by other amino acids. Residues buried in the design model are much more conserved than solvent exposed residues. (Lower) All the mutations to the glycine kinks (spheres in the upper model) and tryptophan (W) corner considerably reduced fluorescence; the shape of the designed structure is critical for the designed function. b & c, Bottom (b) and top (c) comparisons of b11L5F side chains colored by relative fluorescence activation scores (upper row) and stability scores (lower row). In the bottom of the barrel, core residues were strongly conserved in both the function and stability selections (b); in the top barrel there is a clear function-stability trade-off with the key DFHBI interacting residues critical for function but far from optimal for stability (c, substitution patterns at these positions are shown on the right). Fluorescence activation and stability scores were derived from n=2 biologically independent experiments with >10-fold sequencing coverage. Standard deviation and confidence interval are provided in Extended Data Fig. 7.

Guided by the comprehensive protein stability and fluorescence activation maps, we combined substitutions at three positions that improved function without compromising stability (V103L, V95AG and V83ILM; Extended Data Fig. 8a,b), and obtained variants with 10-fold higher DFHBI fluorescence that form stable monomers without a disulfide bond (b11L5F.1; Extended Data Fig. 8c). The crystal structure of one of the improved variants (b11L5F_LGL; mutant 83L/95G/103L in Extended Data Fig. 8b) was solved to 2.2Å and was very close to the design model with the majority of the buried side chains adopting the designed conformation (Extended Data Fig. 9a–d). However, the electron density in the binding site could not be resolved, consistent with the multiple DFHBI binding modes suggested by the docking calculations (Extended Data Fig. 9e–g; docking calculations in Extended Data Fig. 5f). A second round of computational design calculations was carried out to favor a specific binding mode by optimizing the protein-ligand interactions in the lowest energy docked conformation, and to rearrange the hydrophobic packing interactions in the bottom of the barrel now freed from the disulfide bond. Five designs predicted by ligand docking calculations to have a single ligand binding conformation were experimentally tested and three showed increased fluorescence activity, the best of which increased the fluorescence by approximately 1.4-fold (b11L5F.2; Extended Data Fig. 8d–e). Screening of two combinatorial libraries (based on b11L5F.1 and b11L5F.2) incorporating additional beneficial substitutions identified in the b11L5F stability and function maps yielded variants with another 1.5-to-2 fold increased fluorescence and improved protein stability (Extended Data Fig. 8f–h & 10a,b). We refer to these mini- fluorescence-activating proteins as mFAPs in the remainder of the text; mFAP0 and mFAP1 are variants of b11L5F.2, and mFAP2 of b11L5F.1. mFAP1 and mFAP2 activate 0.5 μM DFHBI fluorescence by 80- and 60- fold with KD values of 0.56 μM and 0.18 μM, respectively (Fig. 5d).

Figure 5: Structure and function of mFAPs.

a & b, 2Fo − Fc omit electron density in the mFAP1-DFHBI complex crystal structure contoured at 1.0σ. DFHBI is clearly in the planar Z conformation rather than the non-fluorescent twisted conformations (a). The planar conformation is stabilized by closely interacting residues (b). c, Superposition of mFAP1 design model (silver) and the crystal structure (green). Hydrogen bonds coordinating DFHBI are indicated with dashed lines. d, Fluorescence emission spectra of 0.5µM DFHBI with or without 5µM mFAPs, excited at 467nm. e & f, Confocal micrographs of E.coli cells expressing mFAP2 in the presence of DFHBI (e) and yeast cells displaying Aga2p-mFAP2 fusion proteins on the cell surface (f). Scale bars: 20 μm(e), 10 μm(f). g & h, Overlay of widefield epifluorescence (green) and brightfield (gray) images of fixed COS-7 cells expressing sec61β-mFAP1 (g) and mito-mFAP2 (h, mito- = mitochondrial targeting sequence) with zoomed-in views of the fluorescence in the boxed regions. Scale bars: 20 μm (g&h), 3 μm (zoomed-in views). n=2 biological replicates were performed with similar observation.

The 1.8Å and 2.3Å crystal structures of mFAP0 and mFPA1 in complex with DFHBI were virtually identical to the design models with an overall backbone RMSD of 0.91Å and 0.64Å (Fig. 5a–c & Extended Data Fig. 9h,i). DFHBI is in the planar Z conformation with unambiguous electron density in both structures (Fig. 5a & Extended Data Fig. 9j). In addition to three designed hydrogen bonds, a water molecule was found to interact with the solvent exposed phenol group in DFHBI (Fig. 5b). The DFHBI binding modes in the crystal structures are nearly identical to the lowest-energy docked conformations used in the second round of design calculations, with all-atom RMSD of 0.12Å and 0.35Å respectively (Fig. 5c & Extended Data Fig. 9k). Three mutations shared by mFAP0 and mFAP1 in the bottom barrel (P62D, M65L and L86MorY, Extended Data Fig. 10b) likely stabilize the protein by helical capping and subtle hydrophobic rearrangements (Extended Data Fig. 9l). The M27W mutation in mFAP1 introduced an additional hydrogen bond to DFHBI that likely produces the 5nm red-shift in its fluorescence spectra (Fig. 5d; Extended Data Fig. 10c,e). mFAP2, based on b11L5F.1, has a 6-residue insertion in the seventh β-turn predicted to form multiple intra-loop hydrogen bonds (Extended Data Fig. 10b, right).

In vivo fluorescence activation

To determine whether the designed DFHBI-binding fluorescence-activating proteins function in living cells, we imaged mFAP1- and mFAP2-DFHBI complexes in E.coli, yeast, and mammalian cells by conventional wide field epifluorescence microscopy and confocal microscopy. Both mFAP1 and mFAP2 activated fluorescence in less than 5 minutes following addition of 20µM DFHBI. Cytosolic expression of mFAPs in E.coli and mammalian cells resulted in clear fluorescence throughout the cells (Fig. 5e & Extended Data Fig. 10f). Yeast cells with mFAPs targeted to the cell surface displayed fluorescence in a thin region outside of the plasma membrane (Fig. 5f & Extended Data Fig. 10g). Fusion of the mFAPs to a mitochondria-targeting signal peptide and to the ER localized protein sec61β resulted in fluorescence tightly localized to these organelles in both fixed (Fig. 5g&h) and living cells (Supplementary Videos) with a distribution comparable to that of sec61β-GFP. The quantum yields of mFAP1 and mFAP2 in complex with DFHBI are 2.0% and 2.1%, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 4g, comparable with Y-FAST:HBR31). The brightness of de novo mFAPs in complex with DFHBI is about 35-fold lower than that of eGFP; there is still considerable room for improving their fluorescence activity.

Conclusion

It is instructive to compare the structures of our designed fluorescence-activating proteins with those of natural fluorescent proteins (Fig. 6). Both are β-barrels, and have similar chromophores, but our designs have less than half the residues and narrower barrels connected with short β-turns (Fig. 6a). In both cases, specific protein-chromophore interactions reduce energy dissipation from intramolecular motions32, but the hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic packing around DFHBI is different from GFP and is tailored to the smaller and simpler β-barrel (Fig. 6b). The precise structural control enabled by computational design, together with the greater exposure of the chromophore, may prove useful for fluorescence-based imaging and sensing applications.

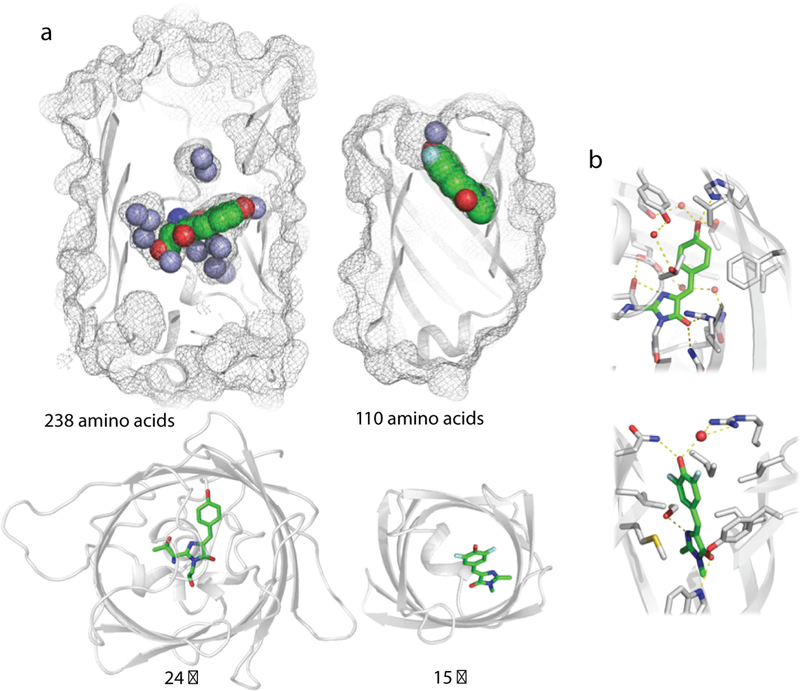

Figure 6: Comparison of structures of GFP and mFAP1.

a, Surface mesh and ribbon representations of structures of GFP (left, PDB ID: 1EMA) and the computationally designed mFAP1 (right) with the chromophores embedded in the protein (green spheres). GFP, a product of natural evolution, has more than twice the number of residues, and a taller (top panel) and wider (bottom panel) barrel. Resolved water molecules in the crystal structures are shown as light purple spheres. b, Close-up of chromophore binding interactions in GFP (left) and mFAP1 (right).

The comparison in figure 6 highlights the two primary advances in this paper: the first successful de novo design of a β-barrel, and the first full de novo design of a small molecule binding protein. The first advance required the elucidation of general principles for designing β-barrels, notably the requirement for systematic symmetry breaking to enable hydrogen bonding throughout the barrel structure. These principles, identified by pure geometric considerations coupled with computer simulations following failure of the initial parametric design approach, are borne out by both the crystal structures and the sequence fitness landscapes. The second advance goes considerably beyond the design of ligand binding proteins and catalysts to date, which has relied on repurposing naturally occurring scaffolds. The three step approach described in this paper — first, identifying the basic principles required for specifying a general fold class, second, using these principles to generate a family of backbones with pocket geometries matched to the ligand or substrate of interest, and third, designing complementary binding pockets buttressed by a deeper hydrophobic core — provides a general solution to the problem of de novo design of ligand-binding proteins. This generative approach allows the exploration of an effectively unlimited set of backbone structures with shapes customized to the ligand or substrate of interest and, equally importantly, provides a critical test of our understanding of the determinants of folding and binding that goes well beyond descriptive analyses of existing protein structures.

Methods

Code availability.

The Rosetta macromolecular modelling suite (http://www.rosettacommons.org) is freely available to academic and non-commercial users. Commercial licenses for the suite are available via the University of Washington Technology Transfer Office. Design protocols and analysis scripts used in this paper are available in the Supplementary Information and on https://dx.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1216229. The source code for RIF docking implementation is freely available at https://github.com/rifdock/rifdock.

Data availability.

The atomic coordinates and experimental data of BB1, b10, b11L5F_LGL, mFAP0-DFHBI, and mFAP1-DFHBI crystal structures have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Database with the accession numbers of 6D0T, 6CZJ, 6CZG, 6CZH, and 6CZI respectively. All the design models, Illumina sequencing data, sequencing analysis and source data (Fig.2 &.4, Extended Data Fig. 6e, 7, 8a&h) are available on https://dx.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1216229.

Computational design of nonfunctional β-barrels.

De novo design of nonfunctional β-barrels can be divided into two main steps: backbone construction and sequence design. For backbone construction, two different approaches were presented: parametric backbone generation and fragment-based backbone assembly. Example scripts and command lines for each method are available in Supplementary Data.

Parametric backbone generation and sequence design based on hyperboloid models.

β-strand arrangements were generated using the equation of a hyperboloid of revolution with an elliptic cross-section, sampling the elliptic radii around the ideal value of β-barrel radius with number of strands ‘n’ and the shear number ‘S’ (see Supplementary Methods). Eight β-strands were arranged as equally spaced straight lines running along the surface of the hyperboloid. A reference Cα was defined as the intersection between the first strand and the cross-section ellipse. The other Cα were systematically populated along the 8 strands from this reference residue. The peptide backbone was generated from the Cα coordinates using the BBQ software38. The arrangements of discrete β-strands were minimized with geometric constraints to favor backbone hydrogen bonds. One round of fixed-backbone sequence design calculation was carried out to pack the barrel cavity with hydrophobic residues. The resulting β-strand arrangements with the best hydrogen bond connectivity and the tightest hydrophobic packing were selected to be connected by short (2 to 4 residues) β-turns. Two iterations of the loop hashing protocol implemented in RosettaRemodel39 were performed to close the strands and refine the turns. The sequence design of those β-turns was constrained to sequence profiles derived from natural proteins. Low energy amino acid sequences were obtained for the connected backbones using a flexible-backbone design protocol (see Supplementary Data). Designs with high sequence propensity for forming β-strands, reasonable peptide bond geometry, and tight-packed hydrophobic cores are selected for experimental test (see Supplementary Table 2).

Backbone assembly from fragments guided by a 2D map.

The presented 2D map (Fig. 1d) was designed with the longest strand length observed in soluble β-barrel structures to obtain a β-barrel tall enough for accommodating a hydrophobic core and a binding cavity. The length of each strand depends on its specific position and the shear number of the barrel (see Supplementary Methods). Glycine kinks and β-bulges were placed on the map as described in the main text. Specific β-turn types were used to connect the β-strands based on their relative positions to β-bulges (see Supplementary Methods). Based on this 2D map, we generated a constraint file and a blueprint file to guide the assembly of the barrel using peptide fragments from Rosetta fragments library. In the constraint file, each backbone hydrogen bond was described as a set of distance and angle constraints (Extended Data Fig. 5b). A set of distance and torsion constraints specific to the tryptophan corner were added to the constraint file (Extended Data Fig.3g–j, and Supplementary Methods). In the blueprint file, a torsion angle bin was attributed to every residue in the peptide chain, according to Rosetta’s ABEGO nomenclature. After minimizing the assembled backbones using Rosetta centroid scoring function with imposed constraints, our protocol output an ensemble of poly-valine β-barrel backbones with defined glycine kinks, β-bulges, β-turns and the backbone of the tryptophan corner. The main challenge in building scaffolds with this protocol is to achieve a good balance between the constraints weight, structure diversity and backbone torsion angles. For this work, we circumvented this problem by performing two additional rounds of sequence design calculation to regularize and prepare scaffolds for designing ligand binding β-barrels (Extended Data Fig. 5b–d and Supplementary Methods).

Sequence design of nonfunctional β-barrels.

500 poly-valine backbones with good hydrogen bonds and torsion angles were selected as input for Rosetta sequence design. Low energy sequences for the desired β-barrel fold were optimized over several rounds of flexible-backbone sequence design. We employed a genetic algorithm to effectively search the sequence space: each parent backbone was used as input to produce 10 designs through individual Monte Carlo searching trajectory. The best ~10% of the output designs were selected based on the evaluation for total energy, backbone hydrogen bonds, backbone omega and phi/psi torsion angles and hydrophobic packing interactions. The selected models were used as inputs for the next round of design calculation. After 12 rounds of design and selection, no more improvements on the backbone quality metrics were observed (an indication of searching convergence). We then performed a backbone refinement by minimization in Cartesian space and a final round of design calculation (backbone flexibility was limited in torsion space for all the design calculation). The final top designs converged to the offspring of 3 initial backbones, sharing 36% to 99% sequence identity. For every parent backbone, one or two designs with the best hydrophobic packing interactions were selected for experimental characterization. The four designs (BB1–4) share 46% to 72% sequence identity.

Computational design of DFHBI-binding fluorescence-activating β-barrels.

DFHBI is short for chemical name ((Z)-4-(3,5-difluoro-4-hydroxybenzylidene)-1,2-dimethyl-1H-imidazol-5(4H)-one). De novo design of DFHBI-binding β-barrels consists of three steps: 1) generation of ensembles β-barrel scaffolds (see above), 2) ligand placement by RIF docking and 3) sequence design. 200 input scaffolds were generated in step 1 and used in the following steps. Example scripts and command lines are available in Supplementary Data.

Rotamer Interaction Field (RIF) docking.

The Rotamer Interaction Field (RIF) docking method performs a simultaneous, high-resolution search of continuous rigid-body docking space as well as a discrete sequence design space. The search is highly optimized for speed and in many cases, including the application presented here, is exhaustive for given scaffold/ligand pair and design criteria. RIF docking comprises two steps. In the first step, ensembles of interacting discrete side chains (referred to as “rotamers”) tailored to the target are generated. Polar rotamers are placed based on hydrogen bond geometry while apolar rotamers are generated via a docking process and filtered by an energy threshold. All the RIF rotamers are stored in ~0.5Å sparse binning of the 6-dimensional rigid body space of their backbones, allowing extremely rapid lookup of rotamers that align with a given scaffold position. To facilitate the following docking step, RIF rotamers are further binned at 1.0Å, 2.0Å, 4.0Å, 8.0Å and 16.0Å resolutions. In the second step, a set of β-barrel scaffolds is docked into the produced rotamer ensembles, using a hierarchical branch-and-bound search strategy (see Extended Data Fig. 5a). Starting with the coarsest 16.0Å resolution, an enumerative search of scaffold positions is performed: the designable scaffold backbone positions are checked against the RIF to determine whether rotamers can be placed with favorable interacting scores. All acceptable scaffold positions (up to a configurable limit, typically 10 million) are ranked and promoted to the next search stage. Each promoted scaffold is split into 26 child positions in the 6D rigid body space, providing a finer sampling. The search is iterated at 8.0Å, 4.0Å, 2.0Å, 1.0Å and 0.5Å resolutions. A final Monte Carlo-based rotamer packing step is performed on the best 10% of rotamer placements to find compatible combinations.

Sequence design of DFHBI-binding β-barrels.

A total number of 2,102 DFHBI-scaffold pairs from RIF docking were continued for Rosetta sequence design. Our design protocol iterated between a fixed-backbone binding site design calculation and a flexible-backbone design for the rest of scaffold positions. Three variations of this design protocol were used during the sequence optimization. In the initial two rounds of design calculation, RIF rotamers (interacting residues placed during RIF docking) were fixed to maintain the desired ligand coordination. Repacking of RIF rotamers was allowed in the final round of design calculation, assuming that the binding sites have been optimized enough to retain these interactions. A Rosetta mover that biases aromatic residues for efficient hydrophobic packing were added after the first round of design. A similar selection approach and Cartesian minimization as described for nonfunctional sequence design were used to propagate sequence search and refine the design models. Evaluations on ligand binding interface energy and shape complementarity were added to the selection criteria. The final set of designs were naturally separated into clusters based on their original RIF docking solutions. For each cluster, a sequence profile was generated to guide an additional two rounds of profile-guided sequence design. 42 designs from 22 RIF docking solutions (20 input scaffolds) were selected for experimental characterization (see Supplementary Table 3).

Post-design model validation and ligand docking simulation.

To validate the protein and ligand conformations of the selected designs, we applied model refinement followed by ligand docking simulation. Protein model refinement was carried out on the unbound model of the designs by running five independent 10-ns MD simulations followed by structural averaging and geometric regularization40. Then ligand docking simulation was performed on this refined unbound structure using RosettaLigand41 using Rosetta energy function42, allowing rigid body orientation and intra-molecular conformation of the ligand as well as surrounding protein residues (both on side chains and backbones) to be sampled. The ligand-binding energy landscapes were generated by repeating 2,000 independent docking simulations.

Design of disulfide bonds.

The disulfide bonds were designed between the N-terminal 3–10 helix and a residue on one of the β-strands on the opposite side to the tryptophan corner. The first 6 residues of the designs model were rebuilt with RosettaRemodel39 and checked for disulfide bond formation using geometric criteria. Once a disulfide bond was successfully placed, the N-terminal helix was redesigned.

Redesign of β-turns for b11.

Three β-turns (loop 3, 5 and 7) surrounding the DFHBI-binding site of b11 were redesigned to make additional protein-ligand contacts. A set of “pre-organized” loops with high content of intra-loop hydrogen bonds and low B-factors were collected from natural β-barrel structures, and used as search template to build individual loop fragment library. Those custom libraries were used as input for RosettaRemodel to build an ensemble of loop insertions in the b11 design model bound to DFHBI. Two rounds of flexible-backbone design calculation were carried out to optimize ligand interface energy and shape complementarity using sequence profiles to maintain the template backbone hydrogen bonds. Designed loop sequences were validated in silico by kinematic loop closure43 (KIC). 500 loop conformations were generated by independent KIC sampling and scored by Rosetta energy function. 36 designs with improved ligand interface energy, shape complementarity and converged loop sampling were selected for experimental characterization (see Supplementary Data and Supplementary Table 6).

Redesign of β-barrel core and DFHBI-binding site for b11L5F.1.

After releasing the disulfide bond in b11L5F, with ligand modeled in the lowest-energy docked conformation for b11L5F (see Extended Data Fig. 5f, right), we performed another round of design calculation to further optimize the β-barrel core packing and ligand binding interactions. The design protocol was very similar to the one used before with fixed ligand hydrogen-bonding residues from RIF docking. 5 designs with 9–15 mutations after manual inspection were selected for experimental characterization.

Protein expression and purification.

Genes encoding the nonfunctional β-barrel designs (41 from parametric design and 4 from fragment-base design) were synthesized and cloned into the pET-29 vector (GenScript, Inc). Plasmids were then transformed into BL21*(DE3) E. coli strain (NEB, Inc). Protein expression was induced either by 1mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 18°C, or by overnight 37°C growth in Studier autoinduction medium. Cells were lysed either by sonication (for 0.5–1L cultures) or FastPrep (MPBio, Inc) (for 5–50mL cultures). Soluble designs were purified by Ni-NTA affinity resin (Qiagen, Inc) and monomeric species were further separated by Akta Pure fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC)(GE Healthcare, Inc) using a Superdex 75 increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare, Inc). 56 genes encoding DFHBI-binding designs were synthesized and cloned into pET-28b vector (Gen9, Inc). Protein expression and purification were carried out in the same way.

Circular dichroism (CD).

Purified protein samples were prepared at 0.5mg/ml in 20mM Tris buffer (150mM NaCl, pH 8.0) or PBS buffer (25mM phosphate, 150mM NaCl, pH7.4). Wavelength scans from 195nm to 260nm were recorded at 25℃, 75℃, 95℃ and cooling back to 25℃. Thermal denaturation was monitored at 220nm or 226nm from 25℃ to 95℃. Near-UV wavelength scan from 240nm to 320nm and tryptophan fluorescence emission were recorded in the absence and presence of 5M guanidinium chloride (GuHCl). Chemical denaturation in GuHCl was monitored by both tryptophan fluorescence and near-UV CD signal at 285nm. The concentration of the GuHCl stock solution was measured with a refractometer (Spectronic Instruments, Inc). Far-UV CD experiments were performed on an AVIV model 420 CD spectrometer (Aviv Biomedical, Inc). Near-UV CD and tryptophan fluorescence experiments were performed on a Jasco J-1500 CD spectrometer (Jasco, Inc). Protein concentrations were determined by 280nm absorbance with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific, Inc). Melting temperatures were estimated by smoothing the sparse data with a Savitsky-Golay filter of order 3 and approximating the smoothed data with a cubic spline to compute derivatives. Reported Tm values are the inflection points of the melting curves.

Size Exclusion Chromatography with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS).

Protein samples were prepared at 1–3mg/ml and applied to a Superdex 75 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) on a LC 1200 Series HPLC machine (Agilent Technologies, Inc) for size-based separation, followed by a miniDAWN TREOS detector (Wyatt Technologies, Inc) for light-scattering signals.

Fluorescence binding assay.

Protein-activated DFHBI fluorescence signals were measured in 96-well plate format (Corning 3650) on a Synergy neo2 plate reader (BioTek, Inc) with λex = 450nm or 460nm and λem = 500nm or 510nm. Binding reactions were performed at 200µL total volume in PBS pH7.4 buffer. Protein concentrations were determined by 280nm absorbance as described above. DFHBI (Lucerna, Inc) were resuspended in DMSO as instructed to make 100mM stock and diluted in PBS to 0.5–10µM.

Library construction.

Deep mutational scanning library for b11L5F were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis as described44. 111 PCR reactions were carried out using DNA oligos directed to each position in two 96-well polypropylene plates (USA Scientific, 1402–9700), and products were pooled and purified by gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Inc) for yeast transformation. Combinatorial libraries for b11L5F.1 and b11L5F.2 were assembled using synthesized DNA oligos (Integrated DNA technologies, Inc) as described45. Selected positions were synthesized with 1–2% mixed bases to control mutation rate and library size. Full-length assembled genes were amplified and purified for yeast transformation as described46.

Yeast surface display and fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS).

Transformed yeast cells (strain EBY100)46 were washed and re-suspended in PBSF (PBS plus 1g/L of BSA). DFHBI in DMSO stock was diluted in PBSF for labeling yeast cells at various concentrations. PBSF-treated cells were incubated with DFHBI for 30 min to 1 hour at room temperature on a benchtop rotator (Fisher Scientific, Inc). Library selections were conducted using GFP fluorescence channel at 520nm with 488nm laser on a SH800 cell sorter (Sony, Inc). Proteolysis treatment and fluorescence labelling were performed in the same way as described30. Cell sorting parameters and statistics for all selections are given in Supplementary Table 16.

Deep sequencing and data analysis.

Pooled DNA samples for b11L5F deep mutational scanning library were transformed twice to obtain biological replicates. Two libraries were treated and sorted in a parallel fashion. Yeast cells of naive and selected libraries were lysed and plasmid DNA was extracted as described47. Illumina adaptor sequences and unique library barcodes were appended to each library by PCR amplification using population-specific primers (see Supplementary Table 8). DNA was sequenced in paired-end mode on a MiSeq Sequencer (Illumina, Inc) using a 300-cycle reagent kit (Catalog number: MS-102–3003). Raw reads were first processed using the PEAR program48 and initial counts analysed with scripts adapted from Enrich49. Stability scores were modeled using sequencing counts from proteolysis sorts as described30. Unfolded states were modeled without disulfide bonds (Cysteine were replaced by Serine). Function scores were modeled using sequencing counts from DFHBI fluorescence sorts. A simple meta-analysis statistical model with a single random effect was applied to combine two replicates using the framework developed in Enrich250.

BB1 crystal structure.

BB1 protein was concentrated to 20 mg/ml in an AMICON Ultra-15 centrifugation device (Millipore, Inc), and sequentially exchanged into 20mM Tris pH8.0 buffer. The initial screening for crystallization conditions was carried out in 96-well hanging drop using commercial kits (Hampton Research, Inc & Qiagen, Inc) and a mosquito (TTP LabTech). With additional optimization, BB1 protein crystallized in 0.1 M BIS-Tris pH 5.0 and 2M ammonium sulfate at 25℃ by hanging drop vapor diffusion with 2:1 (protein: solution) ratio. Diffraction data for BB1 was collected over 200° with 1° oscillations, 5s exposures, at the Advanced Light Source (Berkeley, CA) beamline 5.0.1 on an ADSC Q315R area detector, at a crystal-to-detector distance of 180mm. The data was processed in space group P21 to 1.63 Å using Xia251. The BB1 design model was used as a search model for molecular replacement using the program Phaser52, which produced a weak solution (TFZ 6.5). From this, a nearly complete model was built using the Autobuild module in Phenix53. This required the rebuild-in-place function of autobuild to be set to “False”. Iterative rounds of model building in the graphics program Coot54 and refinement using Phenix.refine55 produced a model covering the complete BB1 sequence. Diffraction data and refinement statistics are given in Supplementary Table18.

b10, b11L5F_LGL crystal structure and mFAPs-DFHBI co-crystal structures.

b10 was initially tested for crystallization via sparse matrix screens in 96-well sitting drops using a mosquito (TTP LabTech). Crystallization conditions were then optimized in larger 24-well hanging drops. b10 crystallized in 100mM HEPES pH 7.5 and 2.1M Ammonium sulfate at a concentration of 38 mg/mL. The crystal was transferred to a solution containing 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5 with 3.4 M Ammonium sulfate and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Data was collected with a home-source rotating anode on a Saturn 944+ CCD and processed in HKL200056.

b11L5F_LGL was concentrated to 19.6 mg/mL (1.58 mM), incubated at room temperature for 30 minuets with 1 mM TCEP then mixed with an excess of DFHBI (re-suspended in 100% DMSO). b11L5F_M11 complexed with DFHBI was screened via sparse matrix screens in 96-well sitting drops using a mosquito (TTP LabTech) and crystallized in 100 mM Bis-Tris pH6.5 and 45% (v/v) Polypropylene Glycol P 400. The crystal was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen directly from the crystallization drop. Data was collected with a home-source rotating anode on a Saturn 944+ CCD and processed in HKL200056.

mFAP0 and mFAP1 were mixed with excess DFHBI (re-suspended in 100% DMSO), while keeping the final DMSO concentration at less than 1%. The mFAP0 and mFAP1 complexes were then concentrated to approximately 41 mg/mL and 64 mg/mL, respectively, and initially tested for crystallization via sparse matrix screens in 96-well sitting drops using a mosquito (TTP LabTech). Crystallization conditions were then optimized in larger 24-well hanging drops macroseeded with poor quality crystals obtained in sitting drops. mFAP0 complexed with DFHBI crystallized in 200 mM Sodium chloride, 100 mM HEPES pH 7.5 and 25% (w/v) Polyethylene Glycol 3350. The crystal was transferred to the mother liquor plus 2 mM DFHBI and 10% (w/v) Polyethylene Glycol 400 then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Data was collected at the Berkeley Center for Structural Biology at the Advanced Light Source (Berkeley, CA), on beamline 5.0.2 at a wavelength of 1.0 Å. and processed in HKL200056. mFAP1 complexed with DFHBI crystallized in 100 mM MES pH6.5 and 12% (w/v) Polyethylene Glycol 20,000. The crystal was transferred to the mother liquor plus 2 M DFHBI and 15% glycerol then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Data was collected with a home-source rotating anode on a Saturn 944+ CCD and processed in HKL200056.

Structures were solved by Molecular Replacement with Phaser52 via phenix53 using the Rosetta design model with appropriate residues cut back to C-alpha and DFHBI removed. The structure was then built and refined using Coot54 and phenix55, respectively, until finished. Diffraction data and refinement statistics are given in Supplementary Table18.

Statistics and reproducibility

(Fig. 1c) The models were colored based on the mean values of repulsion energy by position (Rosetta fa_rep) derived from a set of polyvaline backbones relaxed with constraints (n=189 independently generated models); relaxed with constraints with a glycine in the middle of each Cβ-strip (n=186 independently generated models) and relaxed without constraints with glycines and β-bulges (n=194 independently generated models). This experiment has been performed twice on different sets of backbones and produced similar results. (Fig. 2b–e) BB1 was purified and sized with SEC at least 5 times independently, yielding different ratio of monomeric to oligomeric species (20%−75%). The fraction of monomer could be increased by heat-shocking the cells at 42°C shortly before induction. Two biological replicates of the far and near UV CD and tryptophan fluorescence spectra acquisition of BB1 were done with similar results, and the chemical denaturation experiment performed once. (Extended Data Fig.4a–c) The analysis of BB1 with SEC-MALS was repeated twice on independently prepared protein samples and similar molecular weights were obtained. Additionally, the experiments were repeated on one sample stored at 4°C at different time points (t=0; t=7 days and t=30 days); all experiments had similar results and confirmed the stability of the monomeric species. BB2,3 and 4 were purified once. The molecular weight (with SEC-MALS) and the far UV CD spectra of the purified proteins were tested one time. The sizing of purified BB1 mutants was performed once, with WT BB1 as an internal control.

Cell Culture and Transfection

COS-7 cells (ATCC CRL-1651) were grown in DMEM supplemented with 1x NEAA, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 10% FBS; and harvested using 0.25% Trypsin EDTA. Per transfection, approximately 1 million cells were transfected with 2 µg of plasmid using 18 µL of Lonza SE cell supplement, 82 µL of Lonza SE nucleofection solution and pulse code DS-120 on a Lonza 4D X Nucleofector system. After nucleofection cells were immediately seeded into ibidi µ-Slide 8 well glass bottom chambers at a density of ~30,000 cells/well and incubated overnight at 37 °C.

Cell Fixation

Cells were fixed at 37°C for 10 minutes in PFA/GA fixation solution containing 100 mM aqueous PIPES buffer pH 7.0, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 3.2% paraformaldehyde, 0.1% glutaraldehyde; reduced for 10 minutes with freshly prepared 10 mM aqueous sodium borohydride; then rinsed with PBS for 5 minutes.

Microscopy

Conventional widefield epifluorescence imaging was performed on an inverted Nikon Ti-S microscope configured with a 60 × 1.2 NA water-immersion objective lens (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA), a light emitting diode source (LED4D120, Thorlabs, Newton, NJ, USA), a multiband filter set (LF405/488/532/635-A-000, Semrock, Rochester, NY, USA) and images were captured with a Zyla 5.5 sCMOS camera (Andor, Windsor, CT, USA). The samples were illuminated 470 nm light at an intensity of ~2 W/cm2 and with 200 ms exposures. For live cell experiments, samples were incubated at 37°C with Gibco CO2 Independent Medium containing 50 µM DFHBI for 10 minutes prior to imaging. Time lapse movies were acquired over a period of 5 minutes with a 200 ms exposure every 5 seconds. For fixed cell imaging, samples were incubated at room temperature (~22°C) in PBS containing 50 µM DFHBI for 10 minutes prior to imaging.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1: Parametric design: workflow and shortcomings.

a, Schematic representation of the parametric approach to generate β-barrel designs. b-d, Comparison between β-barrels of type (n=8;S=8, b), type (n=8;S=10, c) and type (n=8;S=12, d); showing an example of 2D map with residue connectivity (top), the arrangement of the Cβs in the Cβ-strips (middle) and the packing pattern of the core side-chains (bottom). The difference in shear number translates into different overall strand staggering and barrel radii. The number of core Cβ-strips (top, middle) results in different arrangements of side-chains in the core of the barrel. e&f, The parametric designs exhibited distorted hydrogen bonds, reflected by the shear distance (defined in e) between paired antiparallel β-strands residues. The shear distance in the design deviate from the distribution observed in native β-sheet proteins (f).

Extended Data Figure 2: Glycine kinks release strain in β-barrel backbones.

a, Fraction of retained hydrogen bond interactions after relaxation with Rosetta (‘relax’) of uniform polyvaline backbones (white) and polyvaline backbones with a glycine in the middle of each Cβ-strip (grey). We compare disconnected strand arrangements generated with the parametric hyperboloid model (n=225 independently generated models), the cylindric model (n=36 independently generated models), the coiled-coil model (n=150 independently generated models) and assembled based on a 2D map (n=144 independently generated models). Center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, minimum and maximum values; points, outliers. b&c, In polyvaline backbones (n=189 independently generated models) relaxed with constraints to maintain hydrogen bonds between strands, several residues have unfavourable left-handed twist (c). The local strand twist is calculated on a sliding window of 4 residues along β-strands, as the angle between the vectors Cα1- Cα3 and Cα2- Cα4. The handedness of the twist is defined as the triple scalar product between these two vectors and the central axis of the barrel. Positive and negative values denote right-handed and left-handed twist, respectively. (b). d, After relaxation (‘FastRelax’), the valine positions in the middle of each Cβ-strip remained in the β-sheet specific ABEGO space (right); or were shifted towards the positive Φ space (E ABEGO) if mutated to glycines (bottom). e, A similar torsion angle distribution was observed for glycines in the β-strands of native β-barrels (n=35 high resolution crystal structures). f, In comparison with regular β-strands (top), the presence of glycine kinks (bottom) increases the local bending of the strands and creates corners in an otherwise circular barrel cross-section. g, The bending angle α is calculated on a sliding window of 3 residues.

Extended Data Fig. 3: Placement of β-bulges, β-turns and the tryptophan corner.

a, Change of curvature (from convex to concave) and protrusion (dashed circle) of the longest hairpin associated with the placement of a glycine kink at position 44. b, relationship between the “corners” in the β-sheet (dashed line) generated by the glycine kinks and the type and position of the β-bulges and β-turns (Supplementary methods). Cα are shown as spheres and colored by ABEGO type. The bottom of the barrel was defined as the side of the N- and C-termini. c, The type I β-turn (‘AA’ ABEGO type) is frequently found at the second position relative to a β-bulge in native proteins and was selected to connect bottom hairpins. d, This choice is further supported by the enrichment of type I (AA) turns over the canonical type I’ turn (GG) in native β-barrels (n=35 high resolution crystal structures). e&f, Poly-valine backbones built with β-bulges and the corresponding β-turns (n=194 independently generated models) retain more hydrogen bonds after relaxation than backbones built without β-bulges and with canonical type I’ β-turns (n=186 independently generated models) (e) and exhibit better scored hydrogen bonds per β-strand residue flanking the β-turns (f). Center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, minimum and maximum values; points, outliers. g, Superposition of tryptophan corner motifs (n=41 high resolution crystal structures) extracted from native β-barrels. h-j, Amino acid preference and torsional constraints derived from the set and used to model the tryptophan corner. Bounded constraints limits are shown as dashed lines.

Extended Data Fig. 4: Biochemical and structural characterizations of designs BB1–4.

a, Results of experimental characterization of the nonfunctional designs (BB1–4). Reproducibility is described in the Methods. †E-value is calculated by BLAST the non-redundant protein database. b, Far-UV CD spectra of designs BB2 and BB3 at 25°C. c, SEC-MALS analysis showed a major monomer peak for BB1 and a major tetramer peak for BB2. d, Variants of BB1 with residues of the tryptophan corner and glycine kinks mutated to alanine were purified and sized. SEC are superimposed to the SEC trace of wild-type BB1 (WT). The mutations of all residues of the tryptophan corner eliminate the monomeric peak. Most of the glycine kink mutations negatively affect the monomeric species. The exceptions are Gly53 and Gly55, which are following each other on the fourth strand. Only one glycine kink per strand might be sufficient to introduce enough negative twist to un-strain the β-barrel. e-f, Deviations between BB1 design model and crystal structure. (e) One of the three bottom turns of the crystal structure (grey) significantly deviates from the design model (magenta) and forms additional crystal contacts (indicated by a dashed circle). (f) Three phenylalanine side-chains have different rotameric states. In the crystal structure, Phe41 interacts with Gly53 (which shows the most backbone deviation between the crystal structure and the design) to form an aromatic rescue motif34. It is likely that the Phe rotamers discrepancy reflect a scoring/sampling challenge to accurately capture such aromatic rescue; MD simulation starting from the crystal structure (cyan) was also unable to recover the correct Phe41-Gly53 interaction. g, Biophysical properties (absorbance/fluorescence spectra, quantum yield and binding affinity) of mFAP1 and mFAP2 in complex with DFHBI. Average values from three biological replicates were used for the nonlinear regression to determine the KD. The error estimates are the standard deviation from the fitting calculation. *λabs is peak absorbance wavelength, λex is peak excitation wavelength and λem is peak emission wavelength. †Absolute quantum yield is measured with an integrating sphere; Relative quantum yield is measured using acridine yellow and fluorescein as the standards. ‡reported value26. §From37. ||From31.

Extended Data Fig. 5: RIF docking grid-based search algorithm, β-barrel scaffold construction and post-design ligand docking simulations.

a, Illustration of grid-based hierarchical search strategy in RIF docking. After generating an ensemble of interactions for the target ligand (Figure 3), each one of the selected scaffold is docked into the fixed “rotamer interaction field (RIF)” using the grid-based hierarchical searching algorithm. This search procedure starts from coarse sampling grids to fine sampling grids in 3D space. An example 2D grid scheme is shown in the upper row, from the lowest resolution (coarse sampling, left) to the highest resolution (fine sampling, right). At each searching stage, the backbone is assigned to different grids based on its relative position and the resulting docking configurations are scored. The top-scored backbone positions (highlighted by cyan circles in the 2D scheme) are shown as 3D structures in the lower row for each searching resolution and are continued for the next grid search and scoring. The 3D structure example shown here was streptavidin structure (PDB ID: 1STP) with grid searching resolutions of 8.0Å, 4.0Å, 2.0Å, and 1.0Å. b-d, β-barrel scaffold construction for small molecule binding. Three geometric constraints (b) were used to describe each backbone hydrogen bond and drive the backbone assembly during Rosetta low-resolution centroid modeling. Backbones generated with all three constraints had a very narrow Φ/Ψ distribution as a result of strong constraints (c, Ramachandran plot in upper left, Set 1, density colored in blue); by omitting N-H-O angle constraint, backbone torsion diversity slightly improved (c, upper right, Set 2). These two raw backbone sets yielded few non-redundant RIF docking solutions (d, blue bars). After two rounds of sequence design calculation using Rosetta full-atom force field (Supplementary Methods), regularized backbones (peptide bonds with proper dihedral geometry) and broadened Φ/Ψ distribution (c, Ramachandran plot in the lower row, density colored in orange) yielded more unique RIF docking solutions (d, orange bars). e, Computed metrics for 42 designs ordered and tested. Results from ab initio folding simulation were scaled to 0.0 to 1.0, with 1.0 represents a funnel-shaped folding landscape35. f, Alternative ligand binding conformations revealed by post-design ligand docking simulations. The lowest-energy docking conformation using the design model (by simply taking out the ligand from the pocket) was similar to the designed DFHBI-binding mode (top left, grey; designed binding mode was circled in grey in the energy landscape in the lower row). Docking simulations using MD-refined the apo protein model revealed an alternative equal-energy docking conformation (top right, green) indicated by a green circle in the docking energy landscapes (lower row). Both binding modes rely on three hydrogen bonding residues from RIF docking (upper row).

Extended Data Fig.6: Biochemical and structural characterization of design b10, b32, b11.

a, Size-exclusion chromatogram (SEC) of His6-tagged b10 and b32 after Ni-NTA affinity purification. The monodispersed peaks of absorbance at 280nm of b10 and b32 (cyan and lavender, respectively) have an elution volume compatible with the monomeric β-barrel (14kDa), based on their relative position to the protein standard peaks (dashed line). n biological replicates were performed with similar observation: n=4 for b10, n=5 for b32. b, Comparison of ligand binding pocket in b10 design model (middle, grey) with the crystal structure (left, cyan). The side-chain disagreements are highlighted with a dashed black circle on the right panel. c&d, The designed disulfide bond as a stabilizing mechanism. SEC curves of His6-tagged b11 (purple line) and b38 (dark yellow line) were overlaid to show the appearance of a monomer peak for b11 (the same standard as in a was applied here). A disulfide bond connecting the N-terminal helix to a β-strand (Q1C and M59C, circled in d) along with four mutations of neighboring residues, were introduced into design b38 (dark yellow) to make design b11 (purple). n biological replicates were performed with similar observation: n=3 for b38, n=5 for b11. e, Far-UV circular dichroism(CD) spectra of b10, b32 and b11. Left: spectra at different temperatures within one heating-cooling cycle; Right: thermal melting curves (b10’s CD signal was monitored at 220nm; b32 and b11 at 226nm). b11 likely forms an amyloid-like beta structure at 95°C (left, bottom row) with a negative peak around 226nm36 and refolds back after cooling to 25°C. The thermal stability of b11 decreases when the disulfide was reduced with 1mM tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP) (right, bottom row). Measurements were performed once for each design (n=1). f, Fluorescence emission spectra of b32, b11 and b11L5F in complex with DFHBI. With 200 µM proteins, b32, b11 and b11L5F can activate 10 µM DFHBI fluorescence by 8-, 12- and 18-fold, respectively. n=2 biological replicates were performed with similar results. g, The residues designed to interact with DFHBI contribute to b11 and b32 activity. Single or double knockouts of hydrogen bonding residues (Y71, S23, N17 and T95) and a hydrophobic packing residue (M15) showed decreased fluorescence intensity at 500nm in comparison with the wild-type b11 or b32 (WT). Mutants were purified once for activity measurement. h&i, Re-designed 5-residue fifth turn in b11L5F. The original bulge-containing “AAG” β-turn in b11 (Extended Data Fig. 3b) was redesigned into a 5-residues turn. b11L5F was detected by yeast surface display and flow cytometry (i and Supplementary Data). Yeast cells displaying b11 and b11L5F showed an increased 520nm fluorescence signal (excited by 488nm laser, i). n=3 biological replicates were performed with similar observation.

Extended Data Fig. 7: Deep mutational scanning maps for b11L5F.

a, The complete function (left) and protease stability (middle and right) landscapes of b11L5F. Fluorescence activation scores, trypsin and chymotrypsin stability scores were calculated as described in Supplementary Methods and demonstrated in the Supplemented Data (b11L5F_DMS_analysis.ipy). n=2 biological replicates with >10-fold sequencing coverage. Red color represents beneficial effect while mutations colored in blue color are detrimental (relative to the wild-type b11L5F). Wild-type residues at each position are indicated by black dots. b, b11L5F backbone model colored by the average stability scores. Glycine backbone Cα are shown as spheres. c&d, Mutational scanning maps of glycine kinks (G25, G43, G53, G55, G81 and G105) and tryptophan corner positions (G9, W9 and R109) (c), and of glycines in the β-turns and prolines (d). e, Statistics of the fluorescence activation and stability scores. The standard deviation between the two replicates used for calculating fluorescence activation scores is smaller than 2 for most the data points (left); 95% confidence interval calculated for the proteolysis/stability analysis is less than 0.25 for most the experimental protease EC50 values (middle and right).

Extended Data Fig. 8: Experimental and computational improvement based on b11L5F.

a-c, Incorporation of point mutations from deep mutational scanning. Beneficial mutations that improve fluorescence activity without compromising protein stability (positive scores relative to wild-type b11L5F; a, left, n=2 biological replicates) were mapped onto b11L5F backbone model (a, right). Purified b11L5F variants incorporating those single, double or triple mutations showed consistently improved fluorescence activity (b). Binding titration curves were obtained for all six possible triple mutants (b, right, n=1 biological measurement). b11L5F with V103L, V95A, V83I, C59V and C1S were renamed as “b11L5F.1” (c). d, Characterization of five designs from the second round of design calculation. Three of the five designs (nC1–5) based on b11L5F showed improved binding activities by titrating purified proteins into 0.5µM DFHBI (d, n=1 biological sample was used for the measurement). The best variant (nC5) was renamed as “b11L5F.2”. e, Ligand docking simulations with the MD-refined apo b11L5F.2. Energy landscape was plotted by comparing all the docking conformations to the design model (left). The lowest-energy docking conformations (highlighted in green circle) match the design model (right, design mode in silver and docking model in green). f&g, Characterization of three best variants (mFAP0–2) from combinatorial library selections. Yeast cells displaying mFAP proteins incubated with 5µM DFHBI analyzed by flow cytometry (f, excited by 488nm laser, n=1 biological sample was used for the measurement with proper controls). Purified proteins showed up to 100-fold fluorescence activation (5µM protein + 0.5µM DFHBI, excited at 450nm and monitored at 500nm and 510nm in a plate reader, n=1 biological measurement). h, Far-UV circular dichroism(CD) characterization of b11L5F.1, b11L5F.2, mFAP0, mFAP1 and mFAP2. Left: spectra at different temperatures within one heating-cooling cycle; Right: thermal melting curves (CD signals were monitored at 226nm, spectra were recorded once (n=1) with internal noise estimation).

Extended Data Fig. 9: Crystal structure of b11L5F_LGL, mFAP0 and mFAP1.

a-g, b11L5F_LGL crystal structure. (Protein samples of all six triple mutants in Extended Data Fig. 8b(right) were prepared for crystallization. b11L5F_LGL with V83L/V95G/V103L combination was successfully crystallized). Crystal contacts between protein copies in one asymmetric unit (yellow) were mediated by two tyrosines (stick representation, grey dashed circle); contacts between three asymmetric units (yellow, blue and green) were formed between β-turns (black dashed circle), which might have displaced one of the top β-turns (c). Overall backbone and side chain conformations in the design model matched the crystal structure with a backbone Cα RMSD of 1.02Å (b, crystal in yellow and design model in silver), and the designed disulfide bond was present in the crystal structure (d). Ligand density in the crystal structure was ambiguous: 2Fo − Fc omit map showing the electron density after refinement without placing DFHBI (e), the best ligand placement to match the density (f), and designed ligand binding interactions (silver) overlaid with the crystallized binding pocket (g). h&i, Crystal contacts in the DFHBI-bound structures of mFAP0(h) and mFAP1(i). Contacts between proteins copies in one asymmetric unit were formed around 40V and 54Y (grey dashed circle) that were introduced for helping crystallization (Extended Data Fig. 10a). Contacts between asymmetric units were formed between β-turns (black dashed circle). j, 2Fo−Fc omit electron density of DFHBI in the mFAP0-DFHBI complex crystal structure. DFHBI density contoured at 1.0σ is clear and matches the planar conformation of the ligand (right). k, Superposition of mFAP0 design model (silver) and the crystal structure (magenta). Hydrogen bonds were indicated with dashed lines. e, Helical capping interactions mediated by P62D mutation in mFAP1 crystal structure.

Extended Data Fig. 10: Mapping of mutations introduced into b11 to yield the final brighter variants, biophysical characterization of mFAP1&2, and epifluorescent images. a, Sequence alignment of b11-based DFHBI-binding fluorescence-activating proteins.

Orange boxes indicate mutations or loop insertions introduced by computational design; purple boxes highlight mutations rationally introduced based on the deep mutational scanning maps (Extended Data Fig. 7&8); green boxes indicate mutations or loop insertions that were incorporated during combinatorial library selections; K40V and K54Y in light blue boxes were introduced to help crystal formation (Extended Data Fig. 9h&i). Despite having hydrophobic residues on the surface, mFAP2 remains soluble at 150mg/mL. b, mFAPs mutations mapped on the design models. Common mutations in all three mFAPs were highlighted in bold. c, Absorbance spectra for DFHBI, mFAP1- and mFAP2-DFHBI complexes (n=4 biological replicates with similar observation). d, Extinction coefficient determination for DFHBI at 418nm. e, Normalized absorbance and fluorescence spectra of mFAP1- and mFAP2-DFHBI complex (n=2 biological replicates with similar observation). f&g, Widefield epifluorescence (bottom) and brightfield (top) images of E.coli and yeast cells with 20µM DFHBI. Untransformed E.coli Lemo21 cells (f, left, n=2 biological replicates with similar observation) and yeast EBY100 cells displaying ZZ domain (g, left, n=2 biological replicates with similar observation) were treated with the same amount of DFHBI and imaged in the same way (1000mA 470nm LED and 200ms exposure time).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements