Abstract

Objective:

Stimulated Raman projection tomography (SRPT), a recently developed label-free volumetric chemical imaging technology, has been reported to quantitatively reconstruct the distribution of chemicals in a three-dimensional (3D) complex system. The current image reconstruction scheme used in SRPT is based on a filtered back projection (FBP) algorithm that requires at least 180 angular-dependent projections to rebuild a reasonable SRPT image, resulting in a long total acquisition time. This is a big limitation for longitudinal studies on live systems.

Methods:

We present a sparse-view data-based sparse reconstruction scheme, in which sparsely sampled projections at 180 degrees were used to reconstruct the volumetric information. In the scheme, the simultaneous algebra reconstruction technique (SART), combined with total variation regularization, was used for iterative reconstruction. To better describe the projection process, a pixel vertex driven model (PVDM) was developed to act as projectors, whose performance was compared with those of the distance driven model (DDM).

Results:

We evaluated our scheme with numerical simulations and validated it for SRPT by mapping lipid contents in adipose cells. Simulation results showed that the PVDM performed better than the DDM in the case of using sparse-view data. Our scheme could maintain the quality of the reconstructed images even when the projection number was reduced to 15. The cell-based experimental results demonstrated that the proposed scheme can improve the imaging speed of the current FBP-based SRPT scheme by a factor of 9–12 without sacrificing discernible imaging details.

Conclusion:

Our proposed scheme significantly reduces the total acquisition time required for SRPT at a speed of one order of magnitude faster than the currently used scheme. This significant improvement in imaging speed would potentially promote the applicability of SRPT for imaging living organisms.

Keywords: Sparse reconstruction, iterative reconstruction, stimulated Raman projection, tomography

I. Introduction

The ability to analyze the components in the whole volume of a three-dimensional (3D) system, such as a cell, tissue or a living organism, has great value for cell machinery, quantitative biology, and systems neuroscience [1]–[5]. Such ability enables volumetric imaging techniques to be applied for quantitative and global measurements in a living organism, and to facilitate consistency in observations for longitudinal imaging. A number of imaging techniques have been developed to image the 3D volume of an entire object. Fluorescence microscopy through a confocal or a multiphoton approach provides good sectioning capability with high axial resolution [6], [7]. Such sectioning method requires tightly focused laser beams to acquire an image stack for 3D reconstruction, which can be time-consuming [1]. Light-sheet microscopy (LSM) overcame this limitation by passing a thin plane of light through the sample to generate planar imaging slices [8], [9]. Providing high resolution images with high speed, LSM enables the dynamic, long-term, and 3D imaging of the specimens ranging from single cells to whole embryos [10]–[13]. However, this method has the potential degenerate the image quality when the distance between the sample surface and the objective increases [14]. Optical projection tomography (OPT) can eliminate the image quality deterioration induced in LSM by rotating the sample by 360 degrees around an axis perpendicular to the light path [14]. OPT can produce a 3D image of a specimen with high-isotropic spatial resolution, and the size of the specimen can be up to several millimeters [1], [15]–[19]. Although the abovementioned fluorescence based volumetric imaging techniques are powerful for quantifying cellular proteins or DNA, they are not suitable to analyze cellular metabolites. The fluorescent labeling has low specificity to label distinct metabolites and can strongly perturb biological functions [2]. Therefore, a label-free volumetric imaging approach that can image a 3D volume in a chemically-selective manner is needed.

Based on the Raman scattering effect that reflects fingerprint information of chemical bond vibrations, spontaneous Raman microscopy can map the chemical composition of a sample in a label-free manner [20], [21]. It possesses high-specificity to image cell metabolites in biological samples [21]. However, spontaneous Raman scattering is a weak process, preventing its applications on a large volume even when implemented via a light-sheet or tomography [2], [22]–[30]. The low signal levels block the imaging speed and the strong emission of autofluorescence might hamper or even overwhelm the weak Raman signals [22]. On the other hand, Raman tomography provides low spatial resolution at the scale of millimeters because of the physical nature of the diffused light transport in the medium [31]. Coherent Raman scattering microscopy, including coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) and stimulated Raman scattering (SRS) microscopy [2], [32]–[36], have been reported to enhance the low levels of the Raman signal and prevent strong autofluorescence. However, these Raman-mediated approaches are still subject to the same problems as with confocal-based sectioning imaging for the volumetric chemical imaging. Recently, we reported a stimulated Raman projection tomography (SRPT) method to enable high-speed volumetric chemical imaging of 3D complex systems [37]. This imaging technology utilized Bessel beams to excite molecular vibrations through the SRS process and provided identical spectral information as that of the spontaneous Raman spectroscopy while significantly improved the imaging speed. We have demonstrated that SPRT can be applied to perform 3D imaging of lipid contents in adipose cells within 3 min.

In SRPT, the Bessel beams were scanned in two dimensions to obtain stimulated Raman projection (SRP) images. A series of projection images as a function of the sample rotation angle were used to recover the chemical distribution in a 3D sample volume. The current image reconstruction scheme used in SRPT is based on a filtered back projection (FBP) algorithm. The FBP requires a minimum of 180 angular-dependent projections to reconstruct a reasonable SRPT image. Such a high number of projection images prevent further improvement of the imaging speed. Therefore, it is highly desirable to reduce the required number of projections to decrease both the total acquisition time and the excitation light dose to the sample for longitudinal studies of living systems. In this work, we present a sparse-view data-based sparse reconstruction scheme to accelerate the imaging speed of SRPT by using the sparsely sampled projections at 180 degrees to reconstruct the volumetric information of a specimen. In the scheme, the simultaneous algebra reconstruction technique (SART), combined with total variation (TV) regularization, was used for iterative reconstruction. TV regularization-based reconstruction methods are popular in field of sparse-view or few-view computed tomography [38]–[42]. To better describe the projection process, a pixel vertex driven model (PVDM) that was borrowed from the separable footprint model [43] was developed and used as the projectors. The PVDM was specially modified to make it more suitable for the parallel beam based SRPT, and its performance superiority was then demonstrated by comparing with the distance driven model (DDM). The performance of the proposed scheme was first evaluated with a series of numerical simulations and then its potential for SRPT application was exemplified by mapping lipid contents in adipose cells. Our results collectively demonstrate that the proposed scheme can reconstruct SRPT images with much fewer projections than using the FBP algorithm, and can improve the imaging speed by at least one order of magnitude. This significant improvement in imaging speed would potentially promote the applicability of SRPT for imaging living organisms.

II. Methodology

A. Forward modeling of SRPT

The SRPT imaging system has been described in our previous work [37]. Briefly, two Bessel beams generated by a pair of axicons and an objective lens were utilized as the pump and Stokes beams. Due to the considerable focal lengths of the Bessel beams [44], the detectable SRP signal may be an integration of SRS generation along with the Bessel beam Rayleigh length (or of the interaction length between the beams and the sample) [37].

| (1) |

in which SSRP is the detected SRP signal by photodiode; d is the diameter of the Bessel beam’s central lobe; r0 is the center of the Bessel beam’s central lobe; J0(·) is the 0th order Bessel function; B, βp and βS are constants which can be found in existing literature [37]; L2 − L1 indicates the thickness of the sample (within the Rayleigh length); C(r0, z) is the distribution of the imaginary element of the third-order nonlinear susceptibility χ(3) at the center of the Bessel beam’s central lobe along the beam propagation direction of z; Pp(r0, z) and PS(r0, z) are the powers of the pump and Stokes beams respectively. In SRPT, because the sizes of the pump and Stokes beams are very small, the powers can be regarded as the average power on the focusing plane. Moreover, the central lobe intensity of the Bessel beams passing through the sample can be constant if the sample is always within the depth of focus of the beams. In this case, Pp(r0, z) and PS(r0, z) can be recorded as Pp(r0) and PS(r0).

In SRPT, both single point excitation and single point detection were employed, while the connection between the excitation and detection points were approximated as being perpendicular to the sample plane. Therefore, the SRPT can be considered as parallel beam imaging. By scanning the Bessel beams two-dimensionally on the lateral plane, we can generate a projection image at a certain rotation angle. This generated projection image can be calculated according to the following equation by changing the position of r:

| (2) |

where S(r) is the SRP signal at position of is the imaginary element of the third nonlinear susceptibility at position of (r, z); (r, z) are coordinates for the lateral and propagation directions of the Bessel beams.

By rotating the sample with a step of a small angle, a number of angular-dependent projection images can be found and utilized to reconstruct the SRPT image:

| (3) |

where are the corresponding values at different projection angles.

Equation (3) demonstrates the forward model of SRPT. Using this equation, we can determine angular-dependent projection images as long as we are aware of all the relevant information about the laser beams and the sample. The reconstruction of SRPT recovers the distribution of the imaginary element of the third-order nonlinear susceptibility (C(r, z)) from the measured angular-dependent projection images (S(r; θ)). As can be seen in the following simulations, 180 angular-dependent projection images that were utilized for SRPT reconstruction were generated by projecting the sample to a specific plane while rotating it consecutively at one-degree steps along an axis, using Eq. (3).

B. TV-regularized SART algorithm

Eq. (3) denotes a line integral of C(r, z) from L1 to L2 along the beam propagation direction. Such line integral represents the Radon transform of the unknown or reconstructed quantity. Thus, the forward model of SRPT can be described by the following matrix equation:

| (4) |

where S is the measured SRP image; R is the Radon transform; C is the (unknown) distribution of the imaginary element of the third-order nonlinear susceptibility.

If we acquire a complete data set, the recovery of C from the noisy measurement S can be achieved by applying the FBP algorithm. If the measurements are incomplete, the SRPT images can be reconstructed by solving the following optimization problem:

| (5) |

where is the reconstructed distribution of the imaginary element of χ(3); λ is the regularization parameter and is the TV regularization term [38]:

| (6) |

where the subscripts s, t are the pixel indices in matrix C.

The minimization problem in Eq. (6) can be solved by using various optimization algorithms, such as the steepest descent method and the conjugate gradient method. Here, we used the steepest descent method to determine the steepest descent direction for the TV based minimization problem in Eq. (6) [38]:

| (7) |

where э is a very small positive number. The steepest descent direction can be expressed by the vector d and its unit vector is denoted as .

The solution to the minimization problem in Eq. (5) can be obtained using the SART, which is iterated as [45]:

| (8) |

where Iφ represents the set of index of rays passing through the jth pixel of the reconstructed image when projecting from angle denotes the weight of the jth pixel contributing to the ith ray; N is the total number of pixels in the reconstructed image; Ri is the ith row of the projector; k is the number of corresponding iterations; α is the relaxation factor.

The step-by-step procedure of the TV-regularized SART algorithm can be summarized as [42] [46] [47]:

Initialization: C = 0, C0 =C;

SART iteration reconstruction using a projection model;

Positivity constraint is imposed on the reconstructed image: Cj = 0 when Cj < 0

Compute the residual: dimg = |C − C0|;

- Compute TV minimization term by repeating the following operation Ngrad times:

- Computing d and by using Eq. (7);

- Update: C ← C −

C0 = C;

Repeat Step 2 to Step 6 until there is no considerable change between two adjacent iterations.

There are several parameters which are both crucial and essential, including regularization parameter λ, relaxation factor α, iteration number N of SART, and iteration number Ngrad of TV. Existing research shows that we can empirically determine these parameters [38][39][46][47][48][49][50]. To conduct the comparisons under the same condition, parameters were set as: λ = 0.08, α = l/(l + 0.5(n − 1)) (n is the current iterative number of SART), N=50, and Ngrad = 10 in the simulations and experiments which follow.

C. Pixel vertex driven projection model

In the TV-regularized SART algorithm, we needed to repeatedly calculate projectors during iterative process, as stated in Step 2. The accuracy and computational burden of such projectors are major challenges for iterative reconstruction. The pixel vertex driven model (PVDM) was deduced from the separable footprint (SF) projector by assuming that the parallel beam projection was performed in SRPT. The SF projector has been reported to be more accurate and efficient than that of the distance-driven model (DDM), as can be seen in Supplementary Figure S1, whose capability has been demonstrated in the cone-beam computed tomography [43]. Here, we made some modifications on the SF projector so that it can be applied to parallel beam SRPT. Such PVDM was used to determine the projector of R in Eq. (5) or (8).

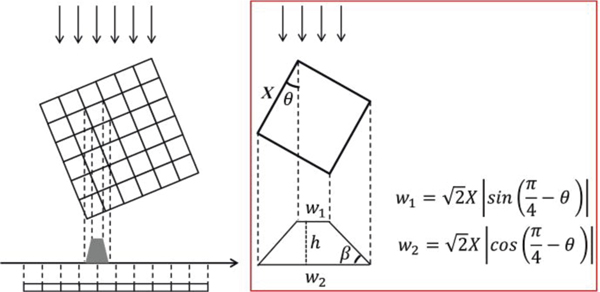

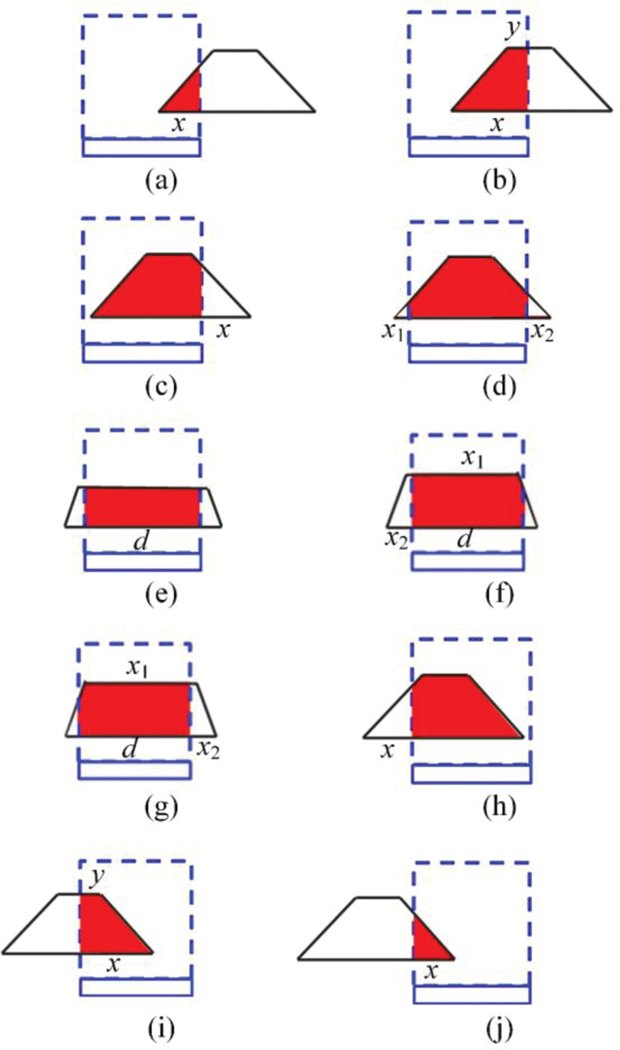

Figure 1 shows the diagram of the PVDM projection model for the parallel beam illumination, where the red rectangle frames the projection of one pixel on the detector. In the forward projector, projecting four vertices of one pixel onto the detector along the beam illumination direction provides the ladder-shaped footprint. In some particular cases, the shape of the footprint can be a rectangle at the projection angles of 0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°, or it can be a triangle at the angles of 45°, 135°, 225°, and 315°. Such diverse projection shapes make the PVDM best approximate the actual physical process of parallel beam projection imaging. The footprint intersects with the detector, and the intersection area denotes the weight of the pixel to the detector. The whole area of one footprint is set to be unity. The weight and the coordinates of the pixel are then recorded for the subsequent back projection. There are ten kinds of intersections for the determination of weight values, as shown in Fig. 2. The calculation of weight values for the ten intersections are detailed in the Appendix.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the pixel vertex driven projection model for the parallel beam illumination. w1 and w2 represent the lengths of the upper and lower edges of the trapezium, while h is the height of the trapezium.

Fig. 2.

Ten kinds of intersections for the determination of weight value.

D. Assessment of image quality

Two evaluation indices, structural similarity (SSIM) and root mean square error (RMSE), were used to evaluate our sparsely reconstructed results. SSIM compares the local patterns of normalized pixel intensities in terms of luminance and contrast [51], [52]. The closer the SSIM is to unity, the better the sparsely reconstructed result is. The SSIM can be calculated as:

| (9) |

where μR and μA are the average values of the reconstructed and reference images, respectively; σR and σA are the standard deviations of the reconstructed and reference images, respectively; σRA is the covariance between them; c1 and c2 are the constants related to the dynamic ranges of the images.

The RMSE is a type of numerical index that can be used to measure the accuracy of an image restoration. The smaller the RMSE, the more accurate the sparsely reconstructed image. RMSE can be calculated as follows [53]:

| (10) |

in which Cxy and are the reconstructed and reference values of the imaginary element of χ(3) on each pixel and N is the pixel number. Here, the original image was used as the reference image for simulation comparisons, and the image reconstructed by using 180 projections was selected as the reference image for the single cell experiment.

III. Experiments and Results

In this section, we describe how the validity and the application potential of the proposed fast SRPT were evaluated with numerical simulations and a single cell based experiment. In the simulations, we compared the sparsely reconstructed images with the original image to determine the minimum number of projection images. A single adipose cell based experiment was also conducted to determine whether the imaging speed efficiency of the proposed SRPT is improved relative to that of the Gaussian beam based SRS sectioning imaging.

A. Simulation verification

The validity of the proposed TV-regularized SART algorithm was evaluated with two groups of numerical simulations. In the evaluation, the data sets employed for sparse reconstruction were constructed by equally sampled complete projections in a half circle, consisting of 180, 90, 60, 45, 36, 30, 15, 9, and 6 projections respectively. For comparisons, the DDM based TV-regularized SART algorithm and the FBP algorithm were applied as the references. A Ramp filter was utilized in the FBP algorithm [54]. For a fair comparison, the same data set was utilized for all three algorithms. The data set was generated by using discrete form of Eq. (3), whose process was very similar to ray-driven model. The generation process can be described as follows. First, by fixing the position of r and the projection angle of θ, the SRP signal can be calculated by integrating Eq. (3) along a light ray. Second, by changing the position of r two-dimensionally, a SRP image can be generated by calculating the SRP signal at each position. Last, a data set of angular-dependent SRP images can be obtained by changing the projection angle of θ and generating the SRP image at each projection angle. To ensure the accuracy of forward projection data, we discretized the detector into 1024 pixels.

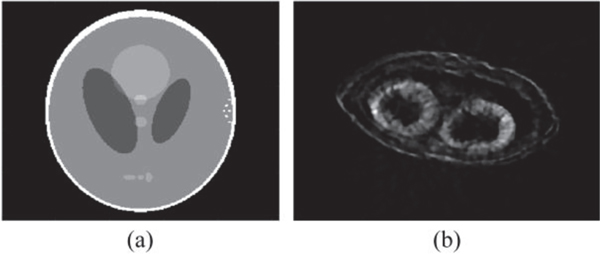

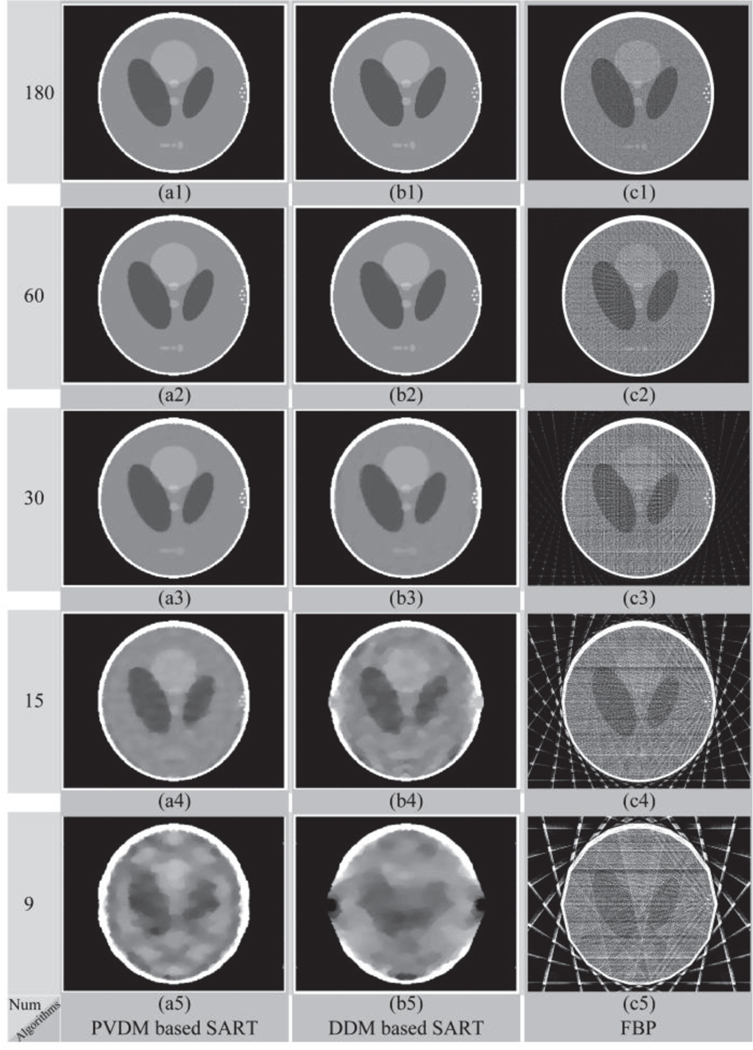

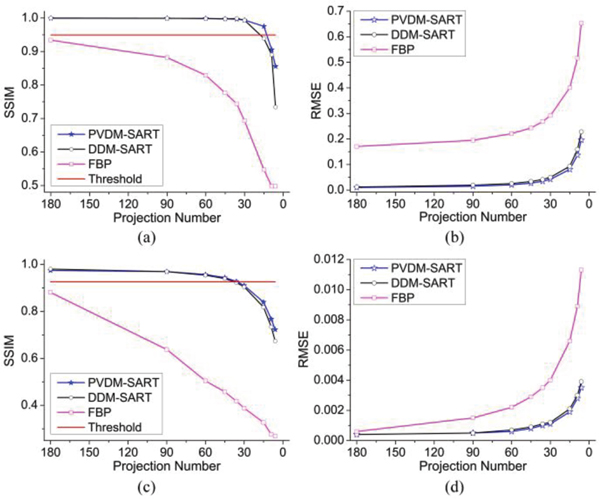

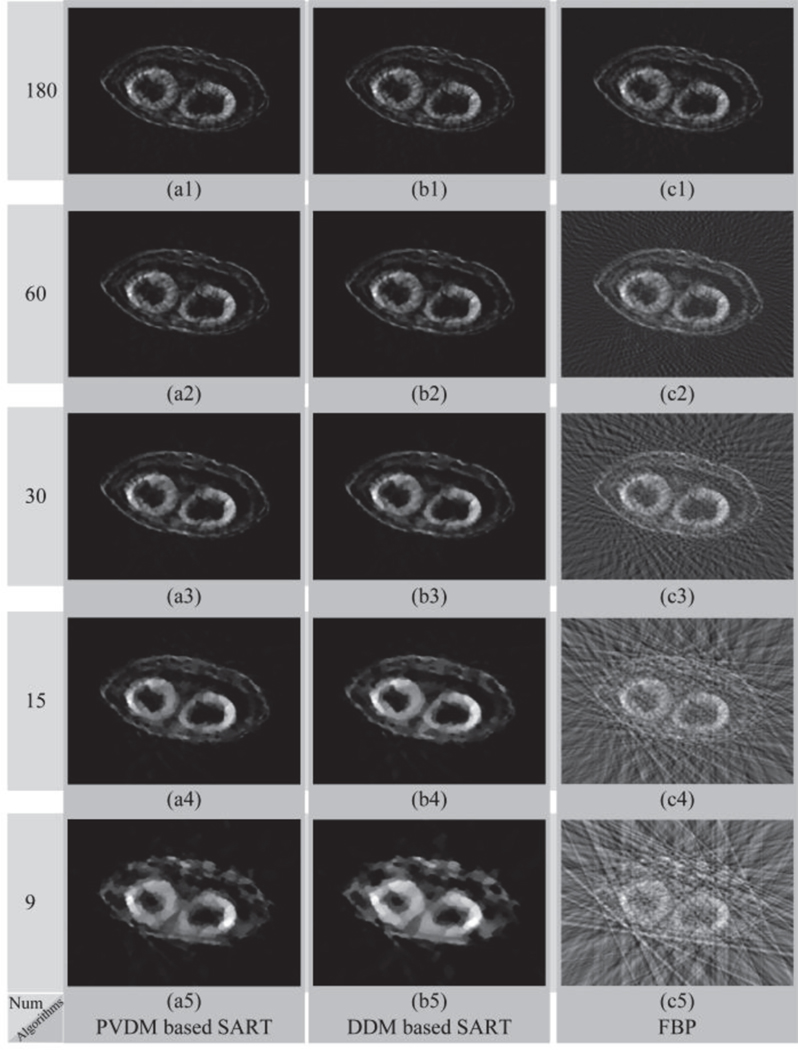

First, a modified Shepp-Logan model was used to perform the evaluation simulations [17]. Figure 3(a) shows the original image of the modified Shepp-Logan model, and the reconstructed images by three algorithms using 180, 60, 30, 15, and 9 projections are presented in Fig. 4. Figure 4(a1-a5) depicts the reconstructed images of the PVDM based TV-regularized SART algorithm, Fig. 4(b1-b5) shows those of the DDM based TV-regularized SART algorithm, and Fig. 4(c1-c5) displays those of the FBP algorithm. We observed that almost the same performance was obtained by the PVDM and the DDM based TV-regularized SART algorithms, which were much better than that obtained by the FBP algorithm. Furthermore, we also found that good quality of the reconstructed images could be maintained even when the projection number was decreased to 30. When the number of projections was reduced to 15, there was some blur observed in the reconstructed images and small details could not be distinguished. Even worse, no acceptable images could be reconstructed when the number of projections was reduced to 9. To quantitatively evaluate the quality of the reconstructed images, we calculated the SSIM and RMSE values. Figure 5(a) and 5(b) show the changes of the SSIM and RMSE values as a function of the projection number respectively. Almost the same performance conclusions were drawn from the SSIM and RMSE curves. The SSIM and RMSE values changed slightly when the projection number was no smaller than 30 for iterative algorithms. However, it decreased (SSIM) or increased (RMSE) dramatically when the number of projections was smaller than 15. Importantly, the proposed PVDM based TV-regularized SART algorithm provided better results than the DDM based one in the sparse views case, for example the projection number was not larger than 60 in this simulation.

Fig. 3.

Original images of the (a) Modified Shepp-Logan model and (b) a cross-section view of the Arabidopsis silique model.

Fig. 4.

Reconstructed results of the modified Shepp-Logan model based simulation. The results reconstructed by the (a) PVDM based SART, (b) DDM based SART, and (c) FBP algorithms; Symbols (1)-(5) represent the number of projections used for reconstruction consisting of 180, 60, 30, 15, and 9 projections, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of SSIM and RMSE values between images reconstructed by three algorithms and the original image. (a)-(b) SSIM and RMSE values as a function of projection number in the modified Shepp-Logan model-based simulation; (c)-(d) SSIM and RMSE values as a function of projection number in the Arabidopsis silique model-based simulation. Blue asterisk lines represent results of the PVDM based SART algorithm, black circle lines are results of the DDM based SART algorithm, and magenta square lines are those of FBP algorithm. Here, the threshold (solid red lines) is defined as ninety-five percent of the best SSIM.

Second, an Arabidopsis silique model was utilized as a physical model in order to generate forward projection images and measure the performance of the proposed algorithm further. Figure 3(b) shows one cross-section of the original image of Arabidopsis silique model. Figure 6 presents the images reconstructed from the sparsely sampled data sets consisting of, respectively, 180, 60, 30, 15, and 9 projections, where the left column shows the results of the PVDM based TV-regularized SART algorithm, the middle column displays the DDM based results, and the right column shows those obtained from the FBP algorithm. Once again, better performance was obtained by applying the iterative algorithms than the FBP. The distribution and shape of the targeted objects could be well recovered by using as little as 30 projections. Even when the projection number was reduced to 15, the reconstructed image still showed little blur. A little distorted or displaying artifact interference was aroused when the number of projections was reduced to 9. The calculated SSIM and RMSE values shown in Fig. 5(c) and 5(d) also gave the same conclusion. It should be noted that the PVDM based TV-regularized SART algorithm provided better results than the DDM based one when the projection number was smaller than 30, showing the good ability in sparse reconstruction from sparse-view data. These results collectively indicate that our TV-regularized SART algorithm can provide satisfactory or acceptable reconstructed images (SSIM>0.9) even when the number of projections is reduced to 15, leading to a 12-fold improvement in imaging speed compared to the current SRPT scheme.

Fig. 6.

Reconstructed results of the Arabidopsis silique model-based simulation. The results reconstructed by the (a) PVDM based SART, (b) DDM based SART, and (c) FBP algorithms; Symbols (1)-(5) represent the number of projections used for reconstruction consisting of 180, 60, 30, 15, and 9 projections, respectively.

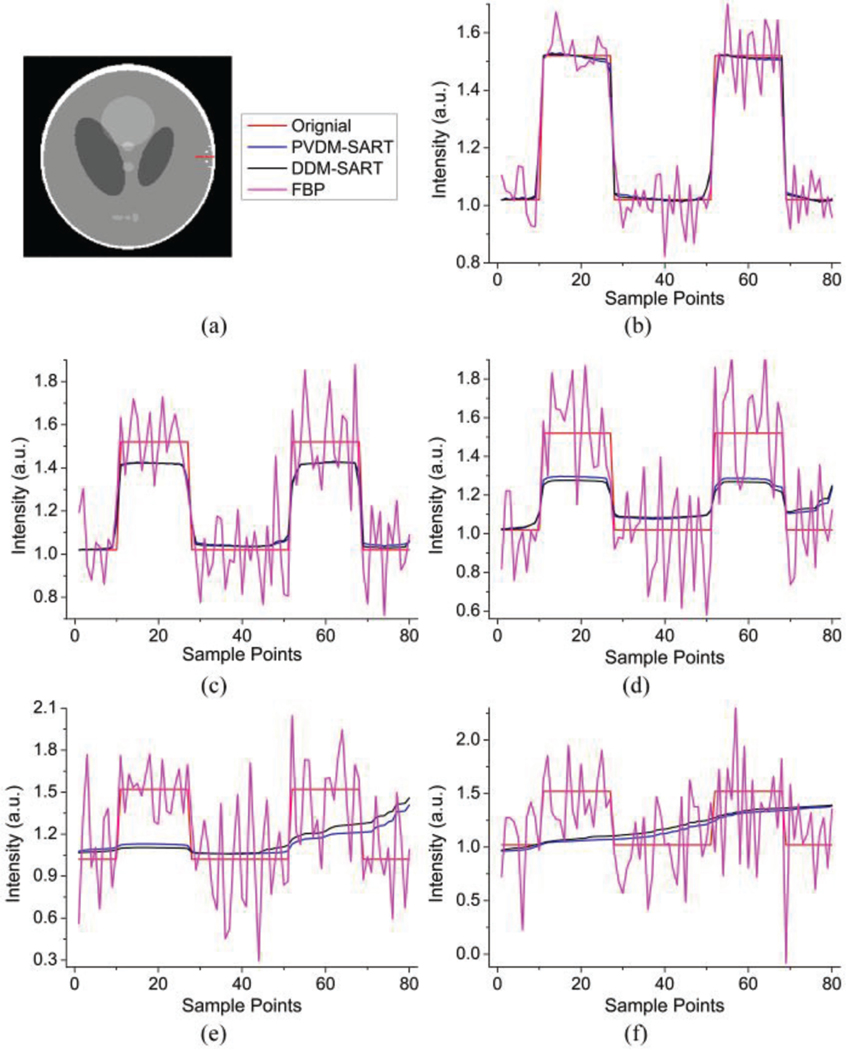

Although the TV-regularized iterative algorithms performed better than the FBP algorithm especially in the case of sparse- view data, they have over-smoothing effects on tiny details. We can see that the images reconstructed by the FBP algorithm look quite sharp in the few-view cases. Even with 15 or nine views, when the images reconstructed by the TV-regularized SART algorithm have been blurred, the edges of the structures in the FBP images are still visible, despite the conspicuous streaks. In the modified Shepp-Logan phantom, there are six dots near to the right side of the skull that are still visible in 15- and nine-view reconstructions, as shown in Figs. 4(c4) and 4(c5). In order to observe this phenomenon more intuitively, we extracted a line across two of six dots in the modified Shepp-Logan phantom, as labeled in Fig. 7(a). Figures 7(b)-7(f) plot the extracted lines of the three reconstruction algorithms by using 180, 60, 30, 15, and 9 projections respectively. The same conclusion can be drawn; which is that the FBP algorithm had a better detail resolution ability in few-view cases. This may be caused by the use of TV regularization, which may over-smooth edges and details [42] [55] [56]. This smoothing effect was influenced by the parameters of the TV regularization. We investigated this potential influence by changing the parameter of Ngrad. We discovered that the larger the Ngrad, the more smoothing the effect would be. If the Ngrad was too small, the quality of the reconstructed image would be worse (see Supplementary Figure S2).

Fig. 7.

Investigation of the detail-resolved ability of different algorithms. (a) Curve extraction position (marked with a red line); (b)-(f) Comparisons of different algorithms with the original line. Blue lines represent the results of the PVDM based SART algorithm, black lines are results of the DDM based SART algorithm, magenta lines are those of FBP algorithm, and red lines represent the curves of the original image. (b)-(f) show comparison results for 180, 60, 30, 15, and 9 projections, respectively.

B. Applicability-potential demonstration

To further explore the potential of the proposed fast SRPT for live cell imaging, we three-dimensionally imaged lipid droplets (LDs) in adipose cells. Here, differentiated 3T3-L1 cells were used for testing [37]. As a mouse derived cell line, 3T3-L1 is widely used for adipogenesis studies [57], and can differentiate into adipose cells, which accumulate LDs in the cytosol under certain conditions. After the cells were cultured for some time, they were first mixed with 1.5% (w/v) agarose gel in PBS solution. The gel mixture was allowed to set in a cylindrical capillary tube with an inner diameter of ~50 microns. The tube was mounted onto a homemade sample holder for imaging during sample rotation [37]. The rotation was performed at 1o per step for acquisition of 180 projection images. The image pixel dwell time was set to 10 μs and each image contained 300 × 300 pixels. Other imaging parameters were setup as described in our previous publication [37].

The collected projection images were first pre-processed for de-noising and compensation, and then used for reconstructing the distribution of lipids in the cell. By comparing the simulation results with the original image, we had found that the image reconstructed by the iterative algorithms had much better quality than that reconstructed by the FBP algorithm, with the SSIM values being higher even when using 180 projections. Therefore, the image reconstructed by the PVDM based SART algorithm from 180 projections was used as the reference to evaluate the performance of the reconstruction from the sparsely sampled data. Figure 8(a) shows the image reconstructed by the FBP algorithm with 180 projection images, and Fig. 8(b)-(h) show the reconstructed cell and distribution of lipids inside the cell by using 180, 90, 60, 36, 30, 15, 9 projections, respectively. We observed that the quality of the reconstructed image was well maintained until the projection number was reduced to 30. A little distortion could still be seen when the number of the projection was decreased to 15, with little differences observed in the fine structures at the edge of the cell. Obvious differences were observed in morphology until the number of projections was reduced to 9. The SSIM and RMSE values as a function of the projection number were also calculated and shown in Fig. 9, and these results also indicated that a minimum projection number of 30 was required to remain a relatively good reconstruction fidelity. The SSIM value between the images which are reconstructed by the FBP and the PVDM based SART algorithms was 0.9551, and the RMSE between them was 0.3978. By combining the analysis results shown in Fig. 8 and Fig. 9, we could obtain an acceptable reconstructed image when the number of projections was set at around 20. These cell-based experimental results demonstrate the applicability potential of the proposed PVDM based SART algorithm for fast imaging of a single adipose cell. Currently, the image reconstruction scheme used in SRPT is based on the FBP algorithm that requires 180 projection images to rebuild a volumetric image [37]. Thus, the algorithm improved the imaging speed by a factor of 9–12 without sacrificing discernible imaging details.

Fig. 8.

Reconstructed results of the lipid content in a single adipose cell using the FBP algorithm and the proposed SRPT-based imaging scheme. (a) Image reconstructed by the FBP algorithm with 180 projection images; (b)-(h) One section of images reconstructed from sparsely sampled data sets consisting of 180, 90, 60, 36, 30, 15, and 9 projections, respectively.

Fig. 9.

SSIM (a) and RMSE (b) values obtained from the images reconstructed by the PVDM based SART algorithm and the reference image.

IV. Discussion

Due to the non-diffractive property of Bessel excitation beams, SRPT can resolve the 3D distribution of chemicals in a volume through projection imaging and tomographic image reconstruction. The label-free approach in SRPT provides indispensable advantages for imaging living systems. Although the FBP algorithm has been applied to reconstruct a 3D image by SRPT, the high number of projection images required is the bottleneck for improving imaging speed. The slowing down of speed also increases the sample exposure time under intense lasers, augmenting the photo-toxicity risk for living samples. Our newly developed sparse-view data-based sparse reconstruction scheme requires only 15–20 projections to reconstruct a 3D image with acceptable or satisfactory quality. This significant improvement in imaging speed would potentially promote the applicability of SRPT for imaging living organisms.

In the simulation, no obvious differences between the images reconstructed by our proposed scheme and the original image were observed until the number of projections was reduced to 30. As the number of projections was reduced to 15, the image quality was a little worse compared with the original image. This means that our proposed SRPT scheme is around 6~12 times faster than the FBP based algorithm. For the adipose cell based experiment, the minimum number of projections required for reconstruction could also be reduced to 20 or less, which delivers a speed at least 9 times faster than the FBP algorithm. This meant that image acquisition time can be improved from 162 seconds (as in our previous study [37]) to ~16 seconds, which is crucial for longitudinal studies of live systems. In our previous study, [37] we have shown that the SRPT was four times faster than the Gaussian beams based SRS sectional imaging for imaging 3D volumes. Implemented with the sparse-view data-based sparse reconstruction, the SRPT provides at least an order of magnitude improvement in 3D imaging speed compared to the conventional Gaussian beams based SRS imaging.

Like reconstruction algorithm, the projection model is also an important part of iterative reconstruction method in SRPT. Accuracy and computational burden are the main factors we need to consider when choosing projection models. As can be seen from Supplementary Figure S1, PVDM that was deduced from the separable footprint projector has better accuracy than DDM. Especially when the number of projection images is relatively small, the PVDM based reconstruction method shows better image restoration ability (Figs. 4–6). However, the computation time of PVDM is longer than that of DDM. The computation time of PVDM based algorithms is approximately three times longer than the DDM based ones when using 180 projections; this factor decreased as the number of projections decreased (can be seen from Supplementary Figure S3).

Although the image acquisition time can be reduced by the fast SRPT scheme, reconstruction also takes extra time compared to the FBP based SRPT scheme. In the fast SRPT scheme, the calculation of the projectors introduced an additional time-consuming step as compared to the FBP based SRPT scheme. In addition, the cost of the total variation based iteration is slightly higher than that of the FBP reconstruction. Typical reconstruction time of the PVDM based TV-regularized SART algorithm is around 350 seconds, which is two orders of magnitude higher than the FBP algorithm (three seconds). Fortunately, both the calculation of projectors and the iteration reconstruction can be accelerated by applying the graphic processing unit technique. Furthermore, the quality of the images reconstructed by the fast SRPT scheme was much better than that obtained by the FBP algorithm, even when using 180 projections (Fig. 4 and Fig. 6).

V. Conclusion

In conclusion, a sparse-view data-based sparse reconstruction scheme is proposed for SRPT, which combines the PVDM, TV regularization, and SART iteration to reconstruct the 3D distribution of chemicals at a speed of one order of magnitude faster than the FBP based SRPT. We believe that this work will facilitate basic and preclinical applications of the SRPT technique.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Key R&D Program of China under Grant 2018YFC0910602, in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant Nos. 81627807, 11727813, 81871397, and 81571725, in part by the Fok Ying-Tong Education Foundation of China under Grant 161104, in part by the Youth Talent Support Program in Shaanxi Province, in part by Research Fund for Young Star of Science and Technology in Shaanxi Province (2018KJXX-018), in part by the Best Funded Projects of the Scientific and Technological Activities for Excellent Overseas Researchers in Shaanxi Province (2017017), in part by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (JB181203), and in part by a Keck Foundation grant and a National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 grant GM118471.

Appendix

The calculation of the weight value for the ten kinds of intersections is detailed as follows.

Case shown in Fig. 2(a):

| (A1) |

Case shown in Fig. 2(b):

| (A2) |

Case shown in Fig. 2(c):

| (A3) |

Here, S is the whole area of one footprint.

Case shown in Fig. 2(d):

| (A4) |

Case shown in Fig. 2(e):

| (A5) |

Here, d is the size of the detector.

Case shown in Fig. 2(f):

| (A6) |

Case shown in Fig. 2(g):

| (A7) |

Case shown in Fig. 2(h):

| (A8) |

Case shown in Fig. 2(i):

| (A9) |

Case shown in Fig. 2(j):

| (A10) |

Contributor Information

Xueli Chen, Engineering Research Center of Molecular and Neuro Imaging of Ministry of Education and School of Life Science and Technology, Xidian University, Xi’an, Shaanxi 710126, China.

Shouping Zhu, Engineering Research Center of Molecular and Neuro Imaging of Ministry of Education and School of Life Science and Technology, Xidian University, Xi’an, Shaanxi 710126, China.

Huiyuan Wang, Engineering Research Center of Molecular and Neuro Imaging of Ministry of Education and School of Life Science and Technology, Xidian University, Xi’an, Shaanxi 710126, China.

Cuiping Bao, Engineering Research Center of Molecular and Neuro Imaging of Ministry of Education and School of Life Science and Technology, Xidian University, Xi’an, Shaanxi 710126, China.

Defu Yang, Institute of Information and Control, Hangzhou Dianzi University, Hangzhou 310018, China.

Chi Zhang, Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, USA. They are now with the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering/Biomedical Engineering, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215 USA..

Peng Lin, Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, USA. They are now with the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering/Biomedical Engineering, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215 USA..

Ji-Xin Cheng, Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907, USA. They are now with the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering/Biomedical Engineering, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215 USA..

Yonghua Zhan, Engineering Research Center of Molecular and Neuro Imaging of Ministry of Education and School of Life Science and TechnologyXidian University.

Jimin Liang, Engineering Research Center of Molecular and Neuro Imaging of Ministry of Education and School of Life Science and Technology, Xidian University, Xi’an, Shaanxi 710126, China.

Jie Tian, Engineering Research Center of Molecular and Neuro Imaging of Ministry of Education and School of Life Science and Technology, Xidian University, Xi’an, Shaanxi 710126, China.; Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Science, Beijing 100190, China.

References

- [1].Sharpe J, et al. , “Optical projection tomography as a tool for 3D microscopy and gene expression studies,” Science, vol. 296, no. 5567, pp. 541–545, Apr. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cheng JX, and Xie X, “Vibrational spectroscopic imaging of living systems: an emerging platform for biology and medicine,” Science, vol. 350, no. 6264, Art. no. aaa8870, Nov. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Stelzer E, “Light-sheet fluorescence microscopy for quantitative biology,” Nat. Methods, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 23–26, Jan. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Keller P, et al. , “Light-sheet imaging for systems neuroscience,” Nat. Methods, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 27–29, Jan. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fu Q, et al. , “Imaging multicellular specimens with real-time optimized tiling light-sheet selective plane illumination microscopy,” Nat. Commun, vol. 7, Art. no. 11088, Mar. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Katona G, et al. , “Fast two-photon in vivo imaging with three-dimensional random-access scanning in large tissue volumes,” Nat. Methods, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 201–208, Jan. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dana H, et al. , “Hybrid multiphoton volumetric functional imaging of large-scale bioengineered neuronal networks,” Nat. Commun, vol. 5, Art. No. 3997, Jun. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Santi P, “Light sheet fluorescence microscopy: a review,” J. Histochem. Cytochem, vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 129–138, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Power R, Huisken J, “A guide to light-sheet fluorescence microscopy for multiscale imaging,” Nat. Methods, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 360–373, Mar. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Verveer PF, et al. , “High-resolution three-dimensional imaging of large specimens with light sheet based microscopy,” Nat. Methods, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 311–313, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Keller P, et al. , “Reconstruction of zebrafish early embryonic development by scanned light sheet microscopy,” Science, vol. 322, no. 5904, pp. 1065–1069, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ahrens MB, et al. , “Whole-brain functional imaging at cellular resolution using light-sheet microscopy,” Nat. Methods, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 413–420, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chen B, et al. , “Lattice light sheet microscopy: imaging molecules to embryos at high spatiotemporal resolution,” Science, vol. 346, no. 6208, Art. No. 1257998, Oct. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bruns T, et al. , “Sample holder for axial rotation of specimens in 3D microscopy,” J. Microsc Vol. 260, no. 1, pp. 30–36, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shapes J, “Optical projection tomography as a new tool for studying embryo anatomy,” J. Anat, vol. 202, no. 2, pp. 175–181, Feb. 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Boot M, et al. , “In vitro whole-organ imaging: 4D quantification of growing mouse limb buds,” Nat. Methods, vol. 5, no. 7, pp. 609–612, Jul. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhu S, et al. , “Automated motion correction for in-vivo optical projection tomography,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, vol. 31, no. 7, pp. 1358–1371, Feb. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pardo-Martin C, et al. , “High-throughput hyperdimensional vertebrate phenotyping,” Nat. Commun, vol. 4, Art. No. 1467, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lindsey BW, Kaslin J, “Optical projection tomography as a novel method to visualize and quantitate whole-brain patterns of cell proliferation in the adult zebrafish brain,” Zebrafish, to be published. DOI: 10.1089/zeb.2017.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Stewart S, et al. , “Raman imaging,” Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 337–360, Apr. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Abramczyk H, and Brozek-Pluska B, “Raman imaging in biochemical and biomedical applications. Diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer,” Chem. Rev, vol. 113, no. 8, pp. 5766–5781, May 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Oshim Y, et al. , “Light sheet-excited spontaneous Raman imaging of a living fish by optical sectioning in a wide field Raman microscope,” Opt. Express, vol. 20, no. 15, pp. 16195–16204, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Oshima Y, et al. , “Light sheet direct Raman imaging technique for observation of mixing of solvents,” Appl. Spectrosc, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 1115–1120, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Barman I, et al. , “Optical sectioning using single-plane-illumination Raman imaging,” J. Raman Spectrosc, vol. 41, no. 10, pp. 1099–1101, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rocha-Mendoza I, et al. , “Rapid spontaneous Raman light sheet microscopy using cw-lasers and tunable filters,” Biomed. Opt. Express, vol. 6, no. 9, pp. 3449–3461, Sep. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Müller W, et al. , “Light sheet Raman micro-spectroscopy,” Optica, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 452–457, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Schulmerich MV, et al. , “Noninvasive Raman tomographic imaging of canine bone tissue,” J. Biomed. Opt, vol. 32, no. 2, Art. no. 020506, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Demers J, et al. , “Multichannel diffuse optical Raman tomography for bone characterization in vivo: a phantom study,” Biomed. Opt. Express, vol. 3, no. 9, pp. 2299–2305, Sep. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sil S, Umapathy S, “Raman spectroscopy explores molecular structural signatures of hidden materials in depth: universal multiple angle Raman spectroscopy,” Sci. Rep, vol. 4, No. 24, Art. no. 5308, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Demer J, et al. , “Next-generation Raman tomography instrument for non-invasive in vivo bone imaging,” Biomed. Opt. Express, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 793–806, May 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Konovalov A, and Vlasov V, “Theoretical limit of spatial resolution in diffuse optical tomography using a perturbation model,” Quant. Electron, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 239–246, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Evans C, Xie X, “Coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy: chemical imaging for biology and medicine,” Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 883–909, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zaitsu S, Imasaka T, “Continuous-wave multifrequency laser emission generated through stimulated Raman scattering and four-wave Raman mixing in an optical cavity,” IEEE J. Quan. Electron, vol. 47, no. 8, pp. 1129–1135, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ozeki Y, et al. , “High-speed molecular spectral imaging of tissue with stimulated Raman scattering,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 6, no. 12, pp. 845–851, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Camp C Jr., Cicerone M, “Chemically sensitive bioimaging with coherent Raman scattering,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 295–305, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Krafit C, et al. , “Developments in spontaneous and coherent Raman scattering microscopic imaging for biomedical applications” Chem. Soc. Rev, vol. 47, no. 21, pp. 1819–1849, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chen X, et al. , “Volumetric chemical imaging by stimulated Raman projection microscopy and tomography,” Nat. Commun, vol. 8, Art. no. 15117, Apr. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sidky EY, et al. , “Accurate image reconstruction from few-views and limited-angle data in divergent-beam CT,” J. X-ray Sci. Technol, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 119–139, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lu Y, et al. , “Few-view image reconstruction with dual dictionaries,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 173–189, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Yan B, et al. , “NUFFT-based iterative image reconstruction via alternating direciton total variation minimization for sparse-view CT,” Comput. Math. Meth. Med, Article No. 691021, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gopi V, et al. , “Iterative computed tomography reconstruction from sparse-view data,” J. Med. Imaging Health Informatics, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 34–46, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Luo X, et al. , “An image reconstruction method based on total variation and wavelet tight frame for limited-angle CT,” IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 1461–1470, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Long Y, et al. , “3D forward and back-projection for X-ray CT using separable footprints,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, vol. 29, no. 11, pp. 1839–1850, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Duocastella M, Arnold C, “Bessel and annular beams for materials process,” Laser Photonics Rev., vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 607–621, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Andersen AH, and Kak AC, “Simultaneous algebraic reconstruction technique (SART): a superior implementation of the ART algorithm,” Ultrason. Imaging, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 81–94, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Yu H, Wang G, “Compressed sensing based interior tomography,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 54, no. 9, pp. 2791–2805, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Gomi T, et al. , “Evaluation of digital tomosynthesis reconstruction algorithms used to reduce metal artifacts for arthroplasty: a phantom study,” Phys. Medica, vol. 42, pp. 28–38, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Jiang M, Wang G, “Convergence of the simultaneous algebraic reconstruction technique (SART),” IEEE Trans. Image Process, vol. 12, no. 8, pp.957–961, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Jiang M, Wang G, “Convergence studies on iterative algorithms for image reconstruction,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 569–579, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Du Y, et al. , “Evaluation of hybrid SART+OS+TV iterative reconstruction algorithm for optical-CT gel dosimeter imaging,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 61, no. 24, pp. 8425–8439, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Wang Z, et al. , “Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity,” IEEE Trans. Image Processing, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 600–612, Apr. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Correia T, et al. , “Accelerated optical projection tomography applied to in vivo imaging of zebrafish,” Plos One, vol. 10, no. 8, Article No. e0136213, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Chen Q, et al. , “A limited-angle CT reconstruction method based on anisotropic TV minimization,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 58, no. 7, pp. 2119–2141, Mar. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Zeng G, Medical Imaging Reconstruction: A Conceptual Tutorial. Beijing and Berlin, China and Germany: 2010, pp. 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Hashemi S, et al. , “Simultaneous deblurring and iterative reconstruction of CBCT for image guided brain radiosurgery,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 62, pp. 2521–2541, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Bao P, et al. , “Few-view CT reconstruction with group-sparsity regularization,” Int. J. Numer. Meth. Biomed. Eng, vol. 34, Article No. e3101, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Kim E, et al. , “Recent advances in proteomic studies of adipose tissues and adipocytes,” Int. J. Mol. Sci, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 4581–4599, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.