Spinal Nerves

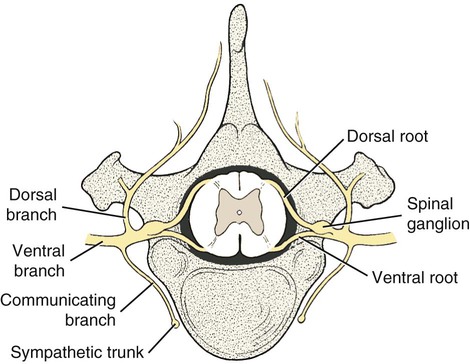

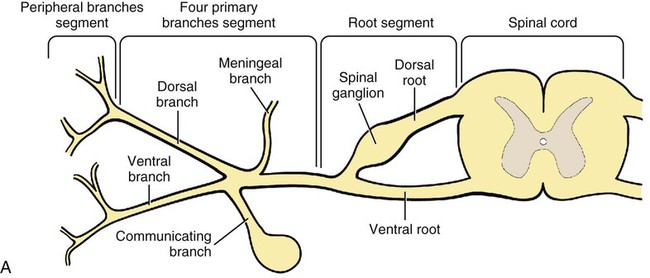

The spinal nerves (nervi spinales) (Figs. 17-1 and 17-2) usually number 36 pairs in the dog. Each spinal nerve consists of four segments from proximal to distal: (1) roots, (2) main trunk, (3) four primary branches, and (4) numerous peripheral branches (Fig. 17-3A). The roots lie within the vertebral canal and consist of a dorsal root (radix dorsalis) with a spinal ganglion (ganglion spinale), and a ventral root (radix ventralis). Each root is formed by a variable number of rootlets (fila radicularia) that attach to the spinal cord. Union of the dorsal and ventral roots forms the main trunk of the spinal nerve, which is located largely within the intervertebral foramen. Within the intervertebral foramen, the spinal nerve gives off a small and variable meningeal branch (ramus meningeus). After emerging from the intervertebral foramen, the spinal nerve gives off a dorsal branch (ramus dorsalis), then a communicating branch (ramus communicans), and continues as a larger ventral branch (ramus ventralis). The dorsal and ventral branches usually subdivide into medial and lateral branches, which give rise to numerous smaller branches.

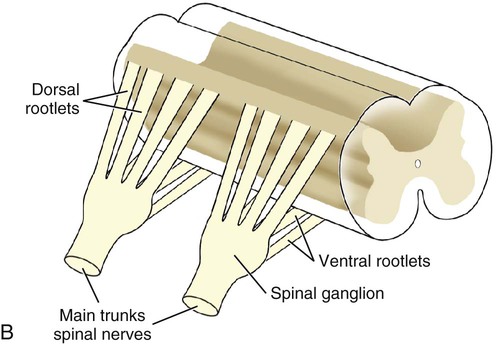

The dorsal and ventral roots are found within the vertebral canal; the spinal ganglion, formerly the dorsal root ganglion, is located in the dorsal root at the junction of the dorsal and ventral roots, near the intervertebral foramen. Each dorsal and ventral root consists of a varying number of rootlets, or root filaments (fila radicularia) (Fig. 17-3B). The dorsal rootlets send axons into the spinal cord at the dorsolateral sulcus. The ventral rootlets emerge from the spinal cord at a wide, indistinct, ventrolateral sulcus. Neither the dorsal nor the ventral roots are compact units. They consist of loosely united bundles of axons, root filaments, that are difficult to differentiate from each other because of the transparency of the covering arachnoid membrane that collapses on them after death. The number of dorsal root filaments agrees closely with the number of ventral root filaments for each spinal nerve. The number of dorsal and ventral root filaments averages six each for the first five cervical nerves. They increase in size and in number to an average of seven dorsal and seven ventral filaments from the fifth cervical segment as far caudad as the second thoracic segment. From the second thoracic segment through the thirteenth thoracic segment there are two dorsal and two ventral filaments that form each thoracic nerve root.

Each dorsal and ventral root is surrounded near the spinal cord by pia and arachnoid trabeculae and then by cerebrospinal fluid in the subarachnoid space. This segment of a nerve root is often referred to as the intradural segment. More distally, a nerve root enters a meningeal tube formed by the arachnoid membrane and the dura mater (Fig. 16-4). This segment of a spinal nerve in a meningeal tube has been referred to as the extradural segment of a spinal nerve root. This is a misleading term because the meningeal tube consists of three layers of meninges, including a small subarachnoid space containing cerebrospinal fluid. If a term is warranted for this section of the roots, the tubular portion describes that component of the roots that is enveloped by all three meningeal layers. At the spinal ganglion, the meninges continue on the main trunk of the spinal nerve and its branches as the epineurium.

Because the vertebral column and the spinal cord continue to grow after birth at different rates (Chapter 16), the total length of the spinal cord is less than the length of the vertebral canal; thus the last several lumbar, the sacral, and the caudal nerves have to run increasingly longer distances before they reach the corresponding intervertebral foramina to exit from the vertebral canal. These roots have much longer intradural as well as tubular segments than do the more cranial roots (Figs. 16-4 and 16-5). Because the caudal part of the spinal cord (S-1 caudally) and the nerves that leave it resemble a horse’s tail, this part of the spinal cord (the conus medullaris), with the spinal roots coming from it, is called the cauda equina (see Chapter 16). The cauda equina is therefore a part of the peripheral nervous system.

Initial or Primary Branches of a Typical Spinal Nerve

Each spinal nerve usually has three or four primary branches arising from the main trunk. Just peripheral to the spinal ganglion, a variable meningeal branch (ramus meningeus) may arise from the main trunk and turn back into the vertebral canal. The meningeal branch consists of afferent (sensory) axons and postganglionic sympathetic axons that supply the dura mater, the dorsal longitudinal ligament, the ventral internal vertebral venous plexus, and other blood vessels located in the vertebral canal (Pederson et al., 1956). The meningeal branch in the dog is microscopic in size (Forsythe & Ghoshal, 1984). They also report that each annulus fibrosus of the intervertebral disk is supplied by meningeal branches from two or more spinal nerves.

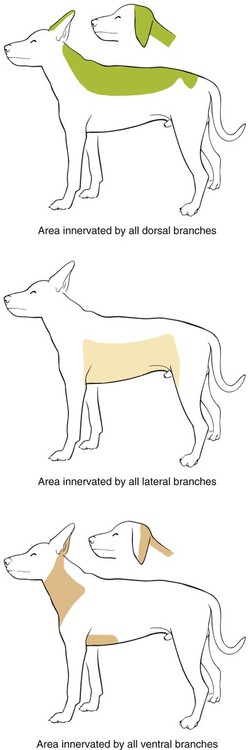

The dorsal branch (ramus dorsalis) of a spinal nerve extends dorsad and usually divides into medial and lateral branches to epaxial muscles and the skin near the dorsal midline (Fig. 17-4).

The ventral branch (ramus ventralis) is the largest of the four primary branches. It divides into medial and lateral branches except where the ventral branches form the large brachial and lumbosacral plexuses or supply the tail. The medial and lateral branches supply hypaxial muscles of the body wall and give off lateral and ventral cutaneous branches that supply the skin of the lateral and ventral aspects of the body wall.

The communicating branch (rami communicantes), also called the visceral branch, differs from the dorsal and ventral branches in that it carries no somatic afferent or somatic efferent axons. It carries only general visceral afferent and efferent axons to and from visceral structures (gland tissue and smooth muscle). The efferent axons are preganglionic sympathetic axons.

The spinal nerves usually leave the vertebral canal through spaces between adjacent vertebrae, the intervertebral foramina. The number of vertebrae and the number of spinal nerves for each vertebral region are not always the same. There are eight pairs of cervical nerves, but only seven cervical vertebrae. In most dogs, there are 20 caudal vertebrae, but only the first five pairs of caudal nerves usually develop.

The three sacral vertebrae are fused to form the sacrum, and there are two dorsal and two ventral pairs of sacral foramina for the passage of the dorsal and ventral branches of the first two pairs of sacral nerves. The third pair of sacral nerves pass through intervertebral foramina located between the sacrum and the first caudal vertebra.

General Features of Spinal Nerves

Functionally, peripheral branches of the dorsal and ventral primary branches of spinal nerves can be classified as sensory nerves with axons from the skin (cutaneous branches) or deeper, nonmuscular structures; motor nerves with efferent axons to muscle and afferent axons from receptors in muscle; or mixed, giving off both sensory and motor branches.

Most spinal nerves leave the vertebral canal through intervertebral foramina formed between the pedicles of adjacent vertebrae. The foramina through which the first cervical nerves pass (the lateral vertebral foramina) are not located between the skull and the atlas, but in the craniodorsal portion of the dorsal arch of the atlas (Fig. 17-2). The second pair of cervical nerves leave the vertebral canal through the first pair of intervertebral foramina, which are located between the atlas and the axis. The last, or eighth, pair of cervical nerves pass through the seventh intervertebral foramina, which are located between the seventh cervical and the first thoracic vertebrae. Therefore the cervical nerves leave the vertebral canal via intervertebral foramina cranial to the vertebra of the same number with the exception of the first and last pairs of cervical nerves. Each spinal nerve from the first thoracic nerve caudally leaves the vertebral canal through the intervertebral foramen caudal to the pedicle of same numbered vertebra. For example, the sixth thoracic spinal nerve leaves the vertebral canal through the intervertebral foramen caudal to the sixth thoracic vertebra.

Peripherally, fasciculi from branches of spinal nerves often intermingle to form plexuses. Two types of plexuses exist. Plexuses supplying the body wall and the appendages are referred to as somatic plexuses. No cell bodies of neurons are located in somatic plexuses; thus no synapses are found in them. Plexuses found around arteries supplying the viscera, and in the walls of visceral organs, are called visceral plexuses. Visceral plexuses may have associated ganglia with cell bodies of autonomic sympathetic neurons in them and thus have synapses occurring within them (see the section on the autonomic nervous system in Chapter 15). Two major somatic plexuses, and a number of minor somatic plexuses, are recognized. The two major somatic plexuses consist of intermingling axons coming from ventral branches of spinal nerves. The brachial plexus (plexus brachialis) serves the thoracic limb, and the lumbosacral plexus (plexus lumbosacralis) serves the pelvic limb.

Cutaneous branches of spinal nerves have a definite pattern of origin from the spinal nerves except for cutaneous branches arising from peripheral branches of the brachial and lumbosacral plexuses (Fig. 17-5). Dorsal cutaneous branches (rami cutaneus dorsales) are only present in cervical nerves III through VI. Here they are branches of the medial branch of the dorsal primary branch of the cervical nerves. In the thoracic and lumbar nerves, medial and lateral cutaneous branches (rami cutaneus medialis et lateralis) arise from the lateral branch of the dorsal primary branch of these spinal nerves. Lateral cutaneous branches also arise from the ventral primary branches of thoracic nerves II through XIII and the first three lumbar nerves of the lumbar plexus. Ventral cutaneous branches (rami cutaneus ventrales) arise from the ventral primary branches of thoracic nerves II through X. There are no lateral or ventral cutaneous branches of cervical nerves and no dorsal cutaneous branches of thoracic or lumbar nerves.

A cutaneous region innervated by afferent axons (dorsal root axons) from a single spinal nerve is termed a dermatome. Dermatomes usually form continuous fields and are arranged serially on the body from cranial to caudal in an overlapping fashion. Most dermatomes overlap to the extent that most skin areas are innervated by receptors from three spinal nerves. The migration and merging of somites provides multiple innervation of the musculature and deeper structures, but not the skin, especially in the skin over the trunk, where autonomous zones are present. The dermatomes in the dog have not been extensively studied except for the caudal thoracic, lumbar, and sacral spinal nerves (Fletcher & Kitchell, 1966b). These are discussed with the nerve supply to the pelvic limb.

Cervical Nerves

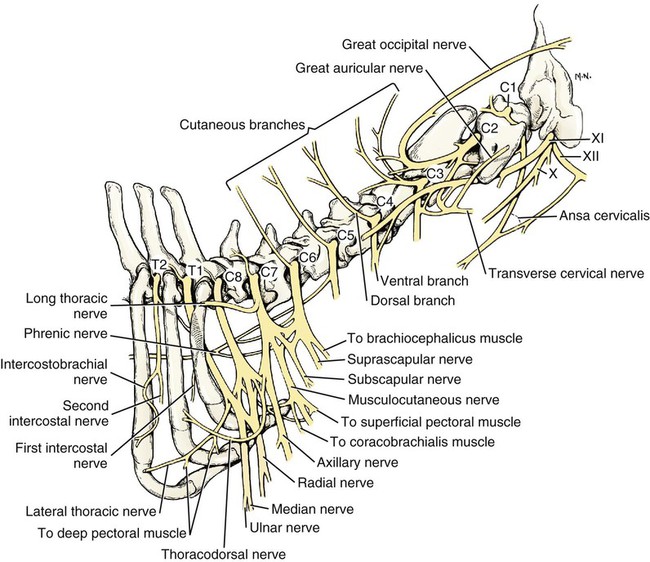

There are eight pairs of cervical nerves (nn. cervicales) (Fig. 17-2), although there are only seven cervical vertebrae. Many ventral branches of cervical nerves communicate with one another and run variable distances in common before joining still other branches. This results in the formation of a variable cervical plexus (plexus cervicalis) that can include axons of all cervical nerves.

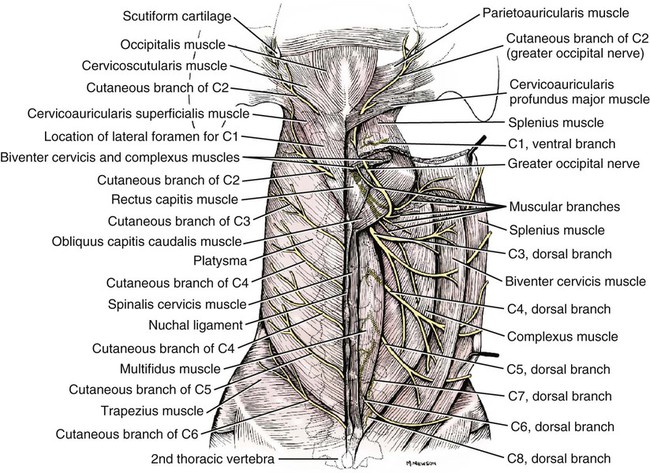

The first cervical nerve (n. cervicalis I) (Fig. 17-2) arises from the first segment of the spinal cord, which is located just caudal to the foramen magnum, and is surrounded by the cranial portion of the atlas. Both its dorsal and its ventral formative root filaments number from three to five and are approximately equal in size. In most specimens a barely distinguishable spinal ganglion is present, whereas in others it may be 1 mm in diameter. On emerging through the lateral vertebral foramen of the atlas, the first cervical nerve divides into dorsal and ventral branches of equal size, measuring approximately 2 mm in diameter.

The ventral branch of the first cervical nerve (ramus ventralis n. cervicalis I) initially lies in the osseous groove of the atlas, which runs transversely to the alar notch from the lateral vertebral foramen. The ventral branch passes through the alar notch and continues in a ventrocaudal direction by passing between the mm. rectus capitis lateralis and rectus capitis ventralis. It is initially covered by the medial retropharyngeal lymph node. After running past the caudal border of this lymph node, the ventral branch continues its course caudally in the neck in close relation to the vagosympathetic nerve trunk. It usually communicates with the smaller descending branch of the hypoglossal nerve to form the cervical loop (ansa cervicalis) (Fig. 17-2). Variations in the formation of the cervical loop are common. (see Benson and Fletcher [1971] regarding the variability of the ansa cervicalis.) In approximately 3% of dogs it fails to develop. The ansa cervicalis may be a long loop measuring 10 cm. Usually the cervical loop extends to a level through the third cervical vertebra, but in some dogs it is short, lying on the carotid sheath approximately 2 cm caudal to the paracondylar process. Several branches arise from the cervical loop. As the sternothyroid and sternohyoid muscles cross the larynx, they each receive a branch from the loop that, according to Benson and Fletcher (1971), comes largely from the hypoglossal nerve. Another branch runs caudad on the trachea and bifurcates near the middle of the neck. The shorter of these branches becomes related to the middle of the lateral border of the m. sternothyroideus before entering its distal portion. The longer branch follows the lateral border of the m. sternohyoideus caudally and enters the muscle approximately 4 cm cranial to the manubrium of the sternum. The ventral branch of the first cervical nerve has no cutaneous branches.

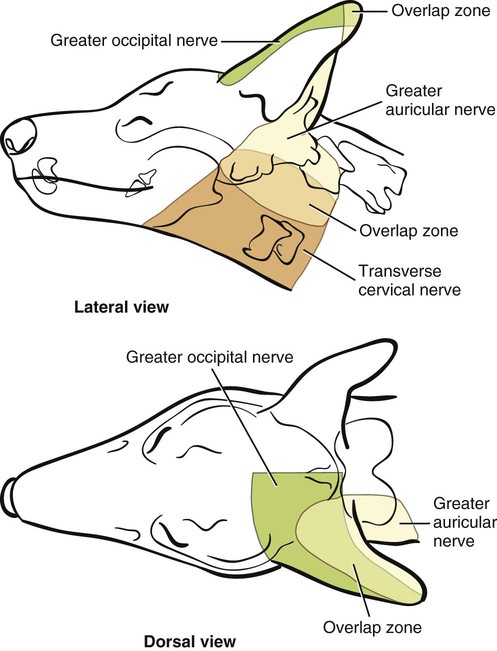

The dorsal branch of the second cervical nerve (ramus dorsalis n. cervicalis II), or the greater occipital nerve (n. occipitalis major), is approximately the same size as the ventral branch (3 mm in diameter in a large dog). It runs caudodorsally (Figs. 17-2 and 17-7), where it is located deep to the obliquus capitis caudalis. Emerging between this muscle and the spine of the axis, it sends muscular branches into the semispinalis capitis and the splenius. It then turns cranially, perforates the overlying muscles, and gives off cutaneous branches to the skin that cover most of the dorsal aspects of the temporal muscle and the medial border and caudal aspect of the pinna (convex surface), including the apex of the pinna (Fig. 17-8). Rostrally its cutaneous area extends around the medial border of the pinna on to the rostral aspect (concave surface) of the pinna, where it overlaps with the rostral border of the cutaneous area of the auricular branches of the facial nerve dorsally and of the auriculotemporal nerve from the mandibular nerve from the trigeminal nerve ventrally (Whalen & Kitchell, 1983a). The rostroventral border of its cutaneous area overlaps the cutaneous area of the frontal nerve, a branch of the ophthalmic nerve from the trigeminal nerve. Caudally, the cutaneous area of the greater occipital nerve overlaps dorsomedially with the cutaneous area of the dorsal cutaneous branch of the third cervical nerve and laterally with the cutaneous area of the greater auricular nerve from the ventral branch of the second cervical nerve on the caudal (convex) surface of the pinna.

The ventral branch of the second cervical nerve (ramus ventralis cervicalis II) runs caudoventrad on the lateral surface of the mastoid part of the cleidocephalicus muscle for 1 or 2 cm and divides into two ventral cutaneous branches, the transverse cervical and great auricular nerves (Fig. 17-2).

The transverse cervical nerve (n. transversus colli), formerly the n. cutaneus colli, runs cranioventrad deep to the platysma and crosses the maxillary and linguofacial veins just before they unite to form the external jugular vein. The nerve may branch before crossing these veins. The branches of this nerve arborize in the skin between the mandibles where its cutaneous area (Fig. 17-8) overlaps with the cutaneous areas of the mylohyoid nerve from the mandibular nerve ventrally and the auriculotemporal nerve from the mandibular nerve from the fifth cranial nerve (Whalen & Kitchell, 1983a).

The great auricular nerve (n. auricularis magnus) is the larger of the two terminal branches of the ventral branch of the second cervical nerve. It runs dorsocranially to the base of the pinna of the ear and divides into at least two branches, which run toward the apex of the ear. Each of these nerves runs approximately midway between the intermediate auricular artery and the peripheral arteries—the lateral and the medial auricular arteries—as they arborize in their course toward the apex of the ear. Variations in both the numbers and the distribution of the arteries and nerves to the pinna are common. The greater auricular nerve has a cutaneous area that covers the lateral two thirds of the caudal (convex) surface and the lateral border of the pinna. The latter overlaps on the rostral (concave) surface (Fig. 17-8). It overlaps with the cutaneous areas of the greater occipital nerve on the caudal surface of the ear and the auricular branches of the seventh cranial nerve on the rostral surface of the ear (Whalen & Kitchell, 1983a).

The dorsal branches of cervical nerves III through VII (rami dorsales nn. cervicales III-VII) (Fig. 17-7) vary in both their distributions and their form. Each of these branches sends a small branch medially into the m. multifidus cervicis. Only their peripheral portions definitely divide into medial (cutaneous) and lateral (muscular) branches. The dorsal branches of cervical nerves III through VII gradually decrease in size caudally. The seventh dorsal cervical branch is reduced to a small muscular branch that innervates only the deep muscle fibers that lie adjacent to it. The dorsal branch of the eighth cervical nerve may be absent. The dorsal branches of the middle cervical nerves perforate the lateral portion of the multifidus cervicis and run dorsally with a slight caudal inclination. On reaching the ventral portion of the biventer cervicis, they usually bifurcate into medial and lateral branches. The third dorsal branch divides near its origin, and the fourth dorsal branch may also divide deeply.

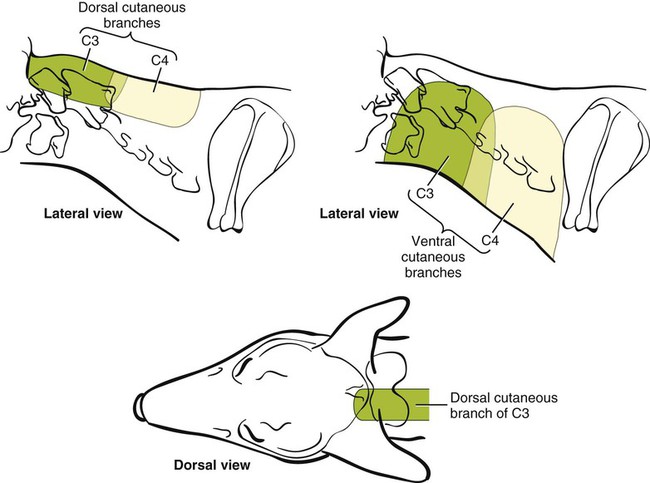

The medial branches of the rami dorsales of cervical nerves III through VII perforate the m. intertransversarius dorsalis and run almost directly dorsad (Fig. 17-7). In their dorsal courses they lie between the multifidus cervicis and spinalis cervicis muscles located medially, and the complexus and biventer muscles (the two portions of the semispinalis capitis) located laterally. The dorsal cutaneous branches are a continuation of these branches of cervical nerves III through VI. They run dorsally in the midline to cross the lateral side of the ligamentum nuchae to reach the skin (Kitchell et al., 1980; Whalen & Kitchell, 1983a). In most specimens the third and fourth medial dorsal cervical branches further divide into cranial (dorsal) and caudal (ventral) parts. They thus appear by their spacing in the subcutaneous fascia as if they were branches of separate cervical nerves. Bilaterally, these dorsal cutaneous branches (rami cutaneus dorsales) innervate the loose, thick skin of the dorsal and adjacent sides of the neck. Their cutaneous areas are aligned in a segmental manner along the dorsum of the cervical region (Figs. 17-9 and 17-10). There are no dorsal cutaneous branches for cervical nerves VII and VIII (Kitchell et al., 1980). The cutaneous area of the dorsal cutaneous branch of cervical nerve VI overlaps with the cutaneous area of the medial cutaneous branch of thoracic nerve II (Fig. 17-10).

The ventral branches of cervical nerves II through V (Fig. 17-6) pass between the muscle bundles of the intertransversarius cervicis to reach the medial surface of the omotransversarius. The ventral branches of cervical nerves II, III, and IV regularly intermingle with the accessory nerve, however, and a connection between cervical nerves II and III is frequent. The ventral branch of the large, second cervical nerve has been described. The ventral branches of the third and fourth cervical nerves supply the skin of the ventrolateral part of the neck (Fig. 17-9) via supraclavicular nerves (nn. supraclaviculares) and smaller medial (muscular) branches (rami mediales) that supply the longus capitis, longus colli, intertransversarius cervicis, omotransversarius, and brachiocephalicus muscles. The medial branches appear as loose clusters of nerves that arise just peripheral to the intervertebral foramina and, after short caudoventral courses, enter the several muscles. The size of the ventral branches of the second to the fifth cervical nerves decreases progressively. The ventral branch of the second cervical nerve is approximately three times larger than that of the fifth. The cutaneous areas of the cutaneous branches of the ventral branches of cervical nerves II through V are quite large (Figs. 17-9 and 17-10). This cutaneous area of cervical nerve V extends onto the brachium, supplying the craniolateral and medial surfaces of that region (Fig. 17-10). Caudodorsally, it overlaps with the cutaneous area of the cutaneous cranial lateral brachial nerve from the axillary nerve. Caudomedially, it overlaps with the cutaneous area of the nerve to the brachiocephalicus, and ventromedially with the cutaneous area of the ventral cutaneous branch of the second thoracic nerve.

Nerves to the Diaphragm

The cervical origins of the phrenic nerve (n. phrenicus) (Fig. 17-2) reflect the fact that the diaphragm that it supplies has a cervical origin. The phrenic nerve regularly arises from the fifth, sixth, and seventh cervical nerves, and occasionally a small branch comes from the fourth.

The branches of origin of the phrenic nerve run caudally, dorsomedial to the brachial plexus. While running in the fascia adjacent to the external jugular vein, these nerve branches converge and unite to form the phrenic nerve just cranial to the thoracic inlet. The nerve on each side then passes through the thoracic inlet ventral to the subclavian artery and dorsal to the superficial cervical artery. At this site it is joined by a fine branch from the middle cervical ganglion or the sympathetic trunk adjacent to the ganglion. Within the thorax the right phrenic nerve lies in a narrow plica of pleura from the right lamina of the cranial and middle mediastinum pleura and the plica venae cavae. The left phrenic nerve lies in a similar plica from the entire left pleural sheet of the mediastinum. Each phrenic nerve spreads out on its respective half of the diaphragm, where it supplies this muscle with motor and sensory fibers. On reaching the diaphragm, each phrenic nerve divides into three main branches: ventral, lateral, and dorsal. This splitting takes place lateral to the middle portion of the tendinous center. Each nerve division supplies its appropriate third of its half of the diaphragm. Each dorsal branch therefore supplies the crus of its side. There usually is a connection between each phrenic nerve and the sympathetic system at the celiac plexus. The periphery of the diaphragm also receives sensory fibers from the last several intercostal nerves (Lemon, 1928). It is generally agreed that the phrenic nerves are the only motor nerves to the diaphragm.

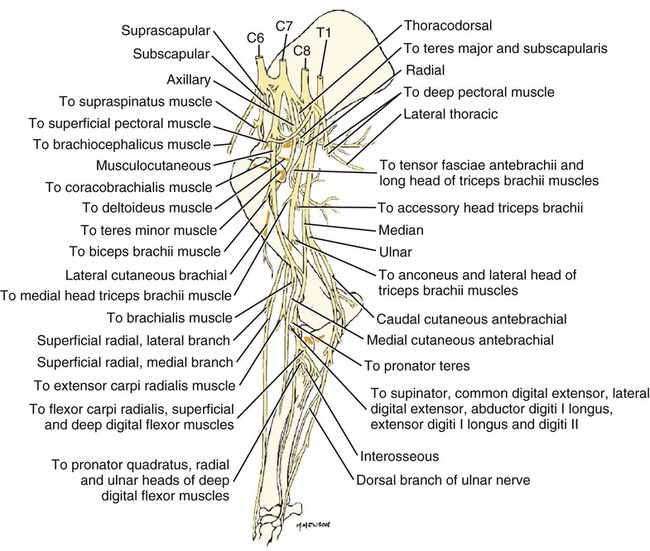

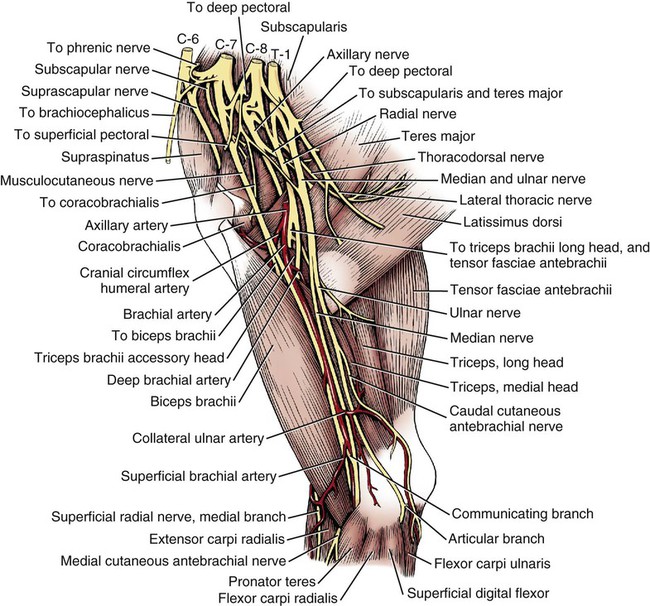

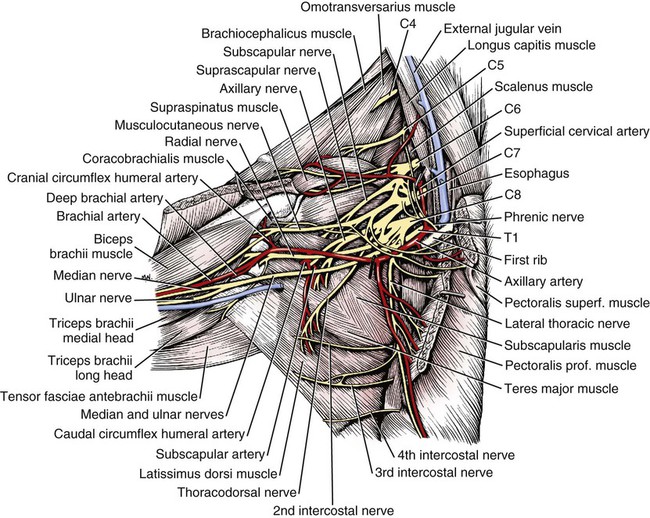

Brachial Plexus

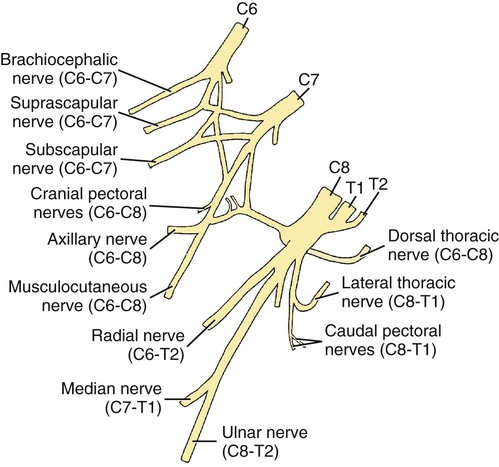

The brachial plexus (plexus brachialis) (Figs. 17-11 to 17-13) is a large somatic nerve plexus that gives origin to the nerves that supply the thoracic limb. It is usually formed by the ventral branches of the sixth, seventh, and eighth cervical and the first and second thoracic spinal nerves. Occasionally, the ventral branch of the fifth cervical nerve also contributes to its formation; frequently, the second thoracic contribution is lacking. When either or both the fifth cervical and the second thoracic spinal nerves send branches that enter into the formation of the brachial plexus, they are exceedingly small compared with the other ventral branches that compose the plexus. In more than 250 dissections, neither one of these nerves was found to be more than 1 mm in diameter. Allam et al. (1952) found in 58 dissections that the fifth cervical and the second thoracic nerve contributions to the brachial plexus are more often absent than present.

Ventral branches of the cervical (C) and thoracic (T) spinal nerves that form the brachial plexus are distributed in a variable manner. They were grouped as follows in dogs studied by Allam et al. (1952): 58.62% formed by C-6, C-7, C-8, and T-1; 20.69% formed by C-5, C-6, C-7, C-8, and T-1; 17.24% formed by C-6, C-7, C-8, T-1, and T-2; and 3.4% formed by C-5, C-6, C-7, C-8, T-1, and T-2.

In an electrophysiologic study of the dorsal (afferent) roots contributing to the cutaneous branches of the nerves arising from the brachial plexus in 8 of 10 dogs, C-6, C-7, C-8, T-1, and T-2 contributed axons; in 1 of 10 dogs, C-6, C-7, C-8, and T-1 contributed; and in another dog, C-5, C-6, C-7, C-8, and T-1 contributed (Bailey et al., 1982). In another electrophysiologic study of the ventral (efferent) root contributions, in six of six dogs, the ventral roots of C-6, C-7, C-8, T-1, and T-2 all contributed efferent fibers to the brachial plexus (Sharp et al., 1990, 1991). After the ventral branches of the last three cervical and the first and second thoracic spinal nerves have passed through the intertransverse musculature, they cross the ventral border of the scalenus muscle and extend to the thoracic limb by traversing the axillary space. In this course, parts of these nerves unite with each other and exit the plexus as various specific named nerves that supply the structures of the thoracic limb and adjacent muscles and skin. The axillary artery and vein lie ventromedial to the caudal portion of the brachial plexus. The external jugular vein, after it has been augmented by the proximal tributary of the cephalic vein, crosses the ventral surfaces of the seventh and eighth cervical nerves, from which it is separated by the superficial cervical artery. The axillary artery, after having crossed the cranial margin of the first rib, lies closely applied to the ventral margin of the scalenus ventralis and later follows along the craniomedial margin of the radial nerve as both the artery and the nerve run distad in the brachium. They are crossed ventrally at the first rib by a muscular nerve branch that goes to the deep pectoral muscle.

Allam et al. (1952) described three cords (trunci plexus) in the brachial plexus of the dog to assist the exploring surgeon by establishing suitable landmarks for electrical stimulation. These cords lie as intermediate nerve trunks between the ventral branches of the spinal nerves that form the plexus and the named nerves that innervate structures of the limb. These trunks vary considerably. For further information on the morphologic features of the brachial plexus of the dog, refer to Russell (1893), Reimers (1925), Miller (1934), and Bowne (1959).

The basic plan of the brachial plexus appears as a variable communication of the last three cervical and first two thoracic nerve ventral primary branches, whose axons run in common for short distances and then segregate in variable combinations to form the extrinsic and intrinsic named nerves of the thoracic limb (Fig. 17-14).

Nerves of the Brachial Plexus That Supply Intrinsic Muscles of the Thoracic Limb

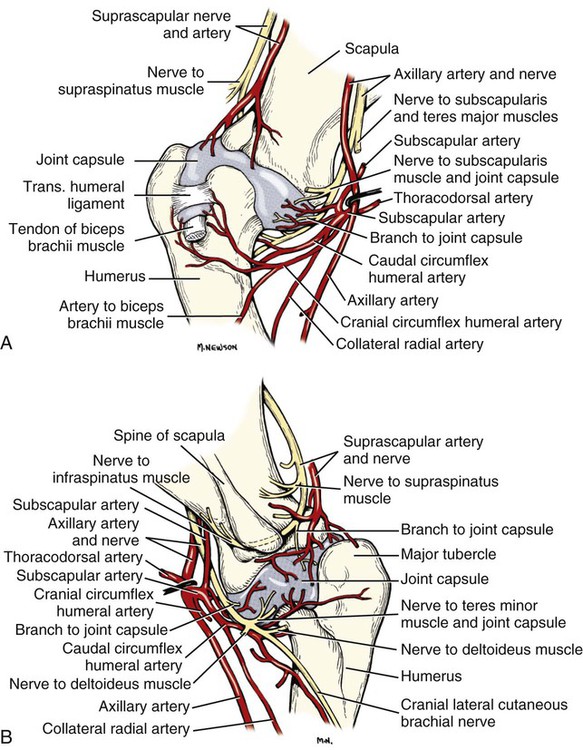

The suprascapular nerve (n. suprascapularis) arises primarily and occasionally entirely from the sixth cervical nerve (Fig. 17-14). It often has a contribution from the seventh, but rarely from the fifth, cervical nerve. According to Sharp et al. (1991), this nerve arose from both C-6 and C-7 in six of six dogs. In this nerve, 65% of the efferent axons arise from C-6, and 34% from C-7. The nerve enters the distal end of the intermuscular space between the mm. supraspinatus and subscapularis from the medial side. It is accompanied by the suprascapular artery and vein. The suprascapular nerve is primarily a muscle nerve to the mm. supraspinatus and infraspinatus. It passes over the scapular notch, innervates the supraspinatus and continues across the neck of the scapula distal to the end of the spine to enter the infraspinatus. Prior to passing distal to the spine the nerve sends a small branch to the lateral part of the shoulder joint (Fig. 17-15). The suprascapular nerve does not have any cutaneous branches in the dog (Kitchell et al., 1980).

The subscapular nerve (n. subscapularis) is usually a single, but occasionally double, nerve that arises from the union of a branch from the sixth and seventh cervical nerves, or if the nerve is double, one part usually arises from the seventh cervical nerve directly (Fig. 17-14). A contribution from the sixth cervical nerve may also be present. It may arise completely or nearly completely from either the seventh or the eighth cervical nerve (Allam et al., 1952). According to Sharp et al. (1991), its efferent supply arises from C-6 and C-7 in six of six dogs; 59% of the efferent axons in this nerve arise from C-6, and 41% from C-7. It usually divides into cranial and caudal parts on entering the medial surface of the distal fifth of the subscapular muscle. The subscapular nerve is approximately 5 cm long in a medium-sized dog. This permits the extensive sliding movement of the scapula on the thorax during locomotion without nerve injury. The subscapular nerve does not have any cutaneous branches (Kitchell et al., 1980).

The axillary nerve (n. axillaris), like the subscapular nerve, is much longer than the distance between its origin and its peripheral fixed end. It arises as a branch from the combined seventh and eighth cervical nerves (Fig. 17-14). A contribution from the sixth cervical nerve may also be present. It may arise completely or nearly completely from either the seventh or the eighth cervical nerve (Allam et al., 1952). According to Sharp et al. (1991), its efferent supply included C-6 in six of six dogs, C-7 in five of six, and C-8 in two of six; 59% of the efferent axons in this nerve arise from C-6, and 41% from C-7, with fewer than 1% from C-8. Bailey et al. (1982) report that C-6 contributed afferent axons to its cutaneous branches in 8 of 10 dogs; C-7, 10 of 10; C-8, 2 of 10. The axillary nerve leaves the axillary space caudodistal to the subscapular muscle and proximal to the teres major muscle. It supplies mainly the muscles of the shoulder joint as it curves around the caudoventral border of the subscapular muscle near its distal end. In its intermuscular course proximocaudal to the shoulder joint, it divides basically into two portions; one part sends branches to caudal fascicles of the subscapular muscle and completely supplies the m. teres major. The other portion, accompanied by the caudal circumflex humeral vessels, runs laterally to supply the laterally lying teres minor and deltoideus. Before entering the teres minor, a branch enters the caudal part of the shoulder joint capsule (Fig. 17-15).

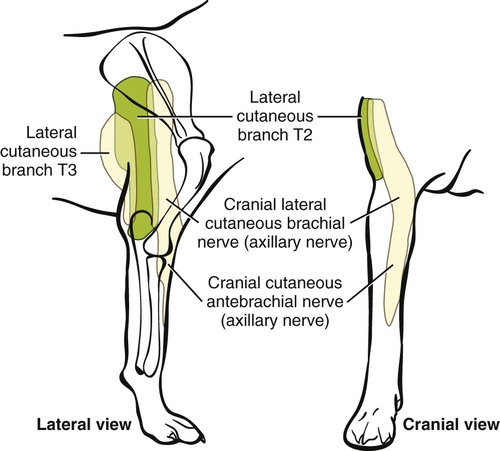

The cranial lateral cutaneous brachial nerve (n. cutaneus brachii lateralis cranialis) leaves the axillary nerve just prior to the entry of this nerve into the deltoid muscle. Therefore it arises lateral to the space between the origins of the lateral and long heads of the triceps muscle. It runs distally on the lateral head of the triceps muscle, where it is covered by the deltoid muscle. It appears subcutaneously caudal to the main portion of the cephalic vein, where it is associated with the cutaneous branches of the caudal circumflex humeral artery and vein (Fig. 17-16). The cutaneous area of this nerve lies on the lateral surface of the brachium (Fig. 17-17), overlapping in its distribution cranial aspects of the cutaneous area of the intercostobrachial nerve (lateral cutaneous branch of thoracic spinal nerve II) caudally and overlapping cranially the caudal aspects of the cutaneous areas of the fifth cervical nerve, dorsally, and the cutaneous branch of the brachiocephalicus nerve, ventrally (Kitchell et al., 1980). On entering the forearm, the cranial lateral cutaneous brachial nerve is named the cranial cutaneous antebrachial nerve (n. cutaneus antebrachii cranialis). It terminates in the skin of the proximocraniolateral aspect of the forearm, where its cutaneous area is completely overlapped by the cutaneous areas of the radial and musculocutaneous nerves (Kitchell et al., 1980). At the elbow joint or just distal to it, it often joins the medial branch of the superficial radial nerve (Fig. 17-16), and by means of this nerve its fibers are carried to the skin of the cranial two thirds of the length of the antebrachium (Kitchell et al., 1980).

The musculocutaneous nerve (n. musculocutaneus) gives muscular branches to the coracobrachialis, biceps brachii, and brachialis (Figs. 17-11 and 17-13). It continues in the forearm as the medial cutaneous antebrachial nerve (Figs. 17-18 and 17-19). The musculocutaneous nerve is irregular in its formation, arising mainly from the seventh cervical nerve but also receiving contributions from C-6 and C-8 (Fig. 17-14). It receives branches from the first and second thoracic nerves in rare instances. According to Sharp et al. (1990) it was formed by contributions from C-6, C-7, and C-8 in six of six dogs and T-1 in two of six; 57% of the efferent axons in the nerve came from C-7, 26% from C-6, and 16% from C-8, with fewer than 1% from T-1. Bailey et al. (1982) found that its cutaneous nerves have a much wider origin, arising in part from C-6 in six of nine dogs, C-7 in nine of nine, C-8 in six of nine, and T-1 in two of nine. Throughout its course in the brachium it lies between or deep to the cranially lying m. biceps brachii and the brachial vessels caudally (Fig. 17-12). There are three muscular branches. Proximally, a small branch goes to the coracobrachialis (Fig. 17-12). This branch is small, and often instead of arising from the musculocutaneous nerve directly it may exist as a separate branch that comes from the eighth cervical or first thoracic nerve, or both. In reaching the coracobrachialis, it follows the cranial circumflex humeral vessels over a portion of its course. A large branch, the proximal muscular branch (ramus muscularis proximalis), often called the muscular nerve to the m. biceps brachii, enters the deep surface of the biceps brachii approximately 4 cm from its origin and near its caudomedial border. In the distal third of the brachium, a communicating branch (ramus communicans cum n. mediano) passes distocaudad, usually medial to the brachial vessels, and joins the median nerve, which with the ulnar nerve lies caudal to the brachial vessels (Figs. 17-12, 17-18 to 17-20). The communicating branch carries both cutaneous (afferent) and efferent axons to the median nerve (Kitchell et al., 1980). The cutaneous afferents from the communicating branch supply a cutaneous area located on the palmar aspect of the forepaw (Fig. 17- 21). This cutaneous area is also supplied by the median nerve axons (described later). The efferent axons go to some of the antebrachial muscles that are supplied by the median nerve. Sharp et al. (1990) reported that efferent axons from the median nerve also go through the communicating branch to supply the brachial muscle. (This communication between the musculocutaneous and the median nerves in the dog is not homologous to the ansa axillaris, according to the Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria [NAV] [1973]). As the musculocutaneous nerve winds deep to the terminal part of the biceps brachii from the medial side, it terminates by dividing into the distal muscular branch (ramus muscularis distalis), also called the muscle nerve to the brachialis muscle (Figs. 17-18 and 17-19), which enters the distal medial portion of the brachialis muscle, and the small medial cutaneous antebrachial nerve (n. cutaneus antebrachii medialis) (Figs. 17-18 and 17-19). This cutaneous branch crosses the lateral side of the tendon of the biceps brachii and enters the cranial surface of the antebrachium from the flexor angle of the elbow joint. As the nerve crosses the cranial surface of the elbow joint, it sends a small branch to the craniolateral part of it (Fig. 17-19). It freely branches in its course distad in the forearm. Its cutaneous area lies on the craniomedial portion of the antebrachium (Fig. 17-21). The cutaneous area of the medial cutaneous antebrachial nerve does not extend into the carpus. The cutaneous area that it supplies is overlapped medially by the cutaneous area supplied by the cutaneous branches of the medial branch of the superficial radial nerve and by cutaneous branches of the axillary nerve and laterally by the cutaneous areas of the caudal cutaneous antebrachial nerve proximally and the cutaneous areas of the median and the dorsal branch of the ulnar nerve distally.

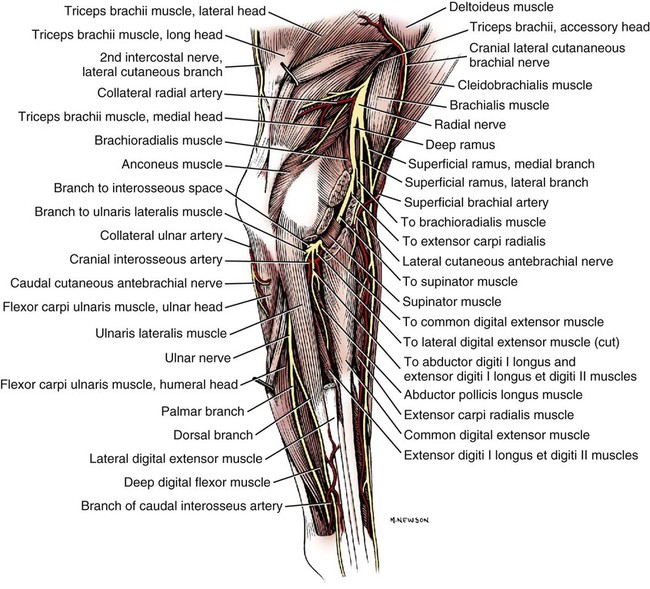

The radial nerve (n. radialis) (Figs. 17-11 to 17-13) arises from the seventh and eighth cervical and the first and second thoracic nerves (Fig. 17-14). According to Sharp et al. (1991) C-7, C-8, and T-1 contributed to the radial nerve in six of six dogs. In five of six, C-6 also contributed. In three of six dogs, T-2 gave some fibers to this nerve. In the radial nerve, 45% of the efferent axons came from C-8, 29% from T-1, 21% from C-7, and 1% from T-2. Bailey et al. (1982) reported that the cutaneous afferent axons in the radial nerve came in part from C-6 in 7 of 10 dogs, from C-7 in 10 of 10, from C-8 in 10 of 10, and from T-1 in only 2 of 10; none came from T-2. The radial nerve is the largest nerve of the brachial plexus. It supplies all the extensor muscles of the elbow, carpal, and digital joints and also the supinator, brachioradialis, and abductor digiti I longus muscles. The skin on the cranial portion of the antebrachium and the dorsal surface of the paw is also supplied by axons of the radial nerve (Fig. 17-22). As the radial nerve approaches the brachium by traversing the axillary space, it lies lateral to the axillary vein and medial to the axillary artery. On crossing the medial surface of the conjoined tendons of the teres major and latissimus dorsi, it lies caudal to the brachial vessels that are the continuation of the axillary vessels after these have crossed the conjoined tendon. It exits from the axilla distal to the conjoined tendons of the teres major and the latissimus dorsi. On entering the interval between the medial and the long heads of the triceps muscle, the radial nerve gives off a small branch to the tensor fascia antebrachial muscle, then divides into a branch that runs proximolateral and is distributed to the long head of the triceps. The second branch runs distolateral and represents the main continuation of the radial nerve. It supplies a branch to the accessory and medial heads of the triceps muscle before it makes contact with the brachialis muscle. Accompanied by the nutrient artery of the humerus, it follows this muscle in a spiral manner around the humerus. On contacting the lateral head of the triceps, it sends a branch to it, and shortly thereafter it bifurcates into deep and superficial branches. Prior to this bifurcation the radial nerve gives off the caudal lateral brachial cutaneous nerve (n. cutaneus brachii lateralis caudalis), which supplies the skin covering the lateral head of the triceps muscle. The deep branch of the distal radial nerve runs deep to the proximocranial border of the extensor carpi radialis. According to Sharp et al. (1990), the deep branch of the radial has a higher percentage of its efferent axons coming from the more cranial roots of the brachial plexus than do the more proximally located muscles supplied by the radial nerve. At the place of bifurcation of the radial nerve, a minute branch runs to the deep surface of the brachioradialis. The superficial branch pursues a more cranial course and becomes superficial between the distocranial border of the lateral head of the triceps and the lateral surface of the deeply lying brachialis muscle.

The deep branch (ramus profundus) supplies all of the extensor muscles of the carpus and the digits (Fig. 17-16). On the lateral aspect of the elbow joint it passes deep to the extensor carpi radialis near its origin from the lateral supracondyloid crest and sends a branch into it (Fig. 17-16). As the deep branch crosses the flexor surface of the elbow joint, it sends an articular branch to the craniolateral part of it (Fig. 17-19). The remaining part of the deep branch then passes deep to the supinator muscle, which it supplies. On emerging from deep to this muscle, it immediately divides into branches that supply the common and lateral digital extensors and a small branch that closely follows the lateral border of the radius and runs distad to innervate the abductor digiti I longus and extensor digiti I longus et digiti II. The distal end of the deep branch of the radial nerve supplies the antebrachiocarpal joint.

The superficial branch (ramus superficialis) of the radial nerve is its more cranial branch (Fig. 17-16). On emerging from deep to the cranial part of the distal border of the lateral head of the triceps muscle, it runs obliquely craniodistad on the brachialis muscle, where it is covered by the thick intermuscular fascia. After running approximately 1 cm in this location, it perforates the thick fascia and divides unevenly into a larger lateral branch (ramus lateralis) and a smaller medial branch (ramus medialis). These branches continue to the carpus in relation to the lateral and medial branches of the cranial superficial antebrachial arteries, respectively. Thus they closely flank the medial and lateral sides of the cephalic vein as they traverse the antebrachium. From the lateral branch of the superficial branch of the radial nerve the usually double lateral cutaneous antebrachial nerve (n. cutaneus antebrachii lateralis) arises. It supplies a variable cutaneous area around and distal to the lateral epicondyle of the humerus (Fig. 17-22). The more proximal branch is the larger and is the branch that is more constantly present. It arises just distal to the flexor surface of the elbow joint, and, associated with relatively large cutaneous branches of the lateral branch of the cranial superficial antebrachial vessels, it supplies the skin of the proximal one third to two thirds of the lateral surface of the antebrachium (Fig. 17-22). The more distally located nerve to the skin of the lateral side of the antebrachium, smaller than the more proximally located nerve, also is accompanied by a cutaneous artery and vein, which serve the cutaneous area of the region. Occasionally, more than two lateral cutaneous antebrachial nerves are present.

Small branches leave both the medial and the lateral branches of the superficial radial nerves and innervate the skin on the cranial surface of the antebrachium (Fig. 17-22). The medial branches of the superficial radial often join the cranial cutaneous branches of the axillary nerve, which results in the cutaneous areas extensively overlapping; however, neither cutaneous area completely overlaps that of the other nerve. Because the medial and lateral branches of the superficial radial nerves also innervate the dorsum of the forepaw, they and their cutaneous areas are described under the description of the nerves to the forepaw.

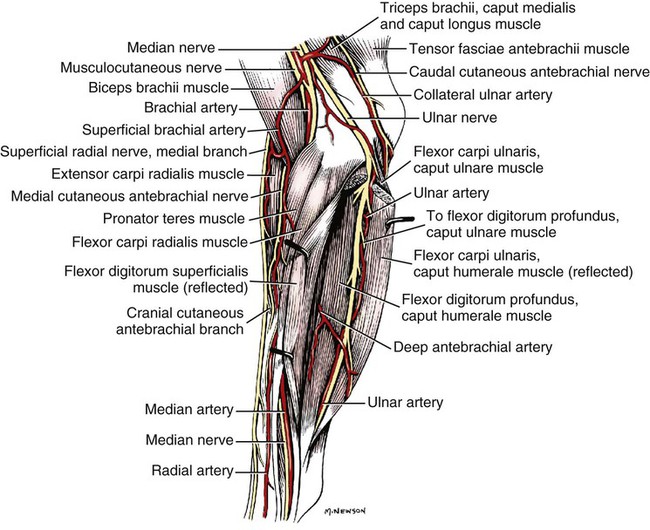

The median nerve (n. medianus) (Figs. 17-11 to 17-13) arises primarily from the eighth cervical nerve by a lateral root (radix lateralis) and first thoracic nerve by a medial root (radix medialis), with small contributions from the seventh cervical and the second thoracic spinal nerves (Fig. 17-14). Before its junction with the communicating branch with the musculocutaneous nerve, Sharp et al. (1990) determined that the efferent axons in the median nerve came from C-8 and T-1 in six of six dogs; from C-7 in five of six; and from T-1 in four of six. Of the total efferent axons in the nerve, 9% came from C-7, 38% from C-8, 46% from T-1, and 6% from T-2. Reimers (1925) did not regard the nerve to be formed until it had received the communicating branch from the musculocutaneous nerve in the distal part of the brachium. He believed that through this communication the median nerve is augmented by axons from the sixth and seventh cervical nerves. Sharp et al. (1990) are in agreement with this deduction in that they determined that of the efferent axons in the communicating branch from the musculocutaneous to the median nerve, 60% came from C-7, 22% from C-8, 2% from T-1, and 17% from T-2. Bailey et al. (1982) found the afferent axons in the cutaneous branches of the median nerve to come in part from C-7 in five of eight dogs, C-8 in eight of eight, and T-1 in eight of eight. Mutai et al. (1986), using horseradish peroxidase, found that the median nerve arose from C-7 through T-1.

The median and ulnar nerves in the forearm lie caudal to the brachial artery and vein, where they are loosely joined by fascia (Fig. 17-12). The median nerve is cranial in relation to the ulnar nerve. The median nerve does not give off any branches proximal to the elbow joint. It crosses the flexor surface of the elbow joint cranial to the medial epicondyle. The median nerve passes deep to the pronator teres and enters the large caudal group of flexor muscles located in the antebrachium (Fig. 17-18). It gives muscular branches to the pronator teres, pronator quadratus, flexor carpi radialis, and flexor digitorum superficialis and the radial head of the flexor digitorum profundus. It also sends axons to the deep part of the humeral head of the flexor digitorum profundus and a small articular branch to the medial aspect of the elbow joint.

On emerging from deep to the pronator teres, to which it sends a small branch, several muscular branches (rami musculares) leave the caudal portion of the nerve (Fig. 17-18). The shortest and most proximal of these nerves enters the flexor carpi radialis close to its humeral origin. The remaining flattened bundle of muscular branches crosses the medial surface of the brachial vessels at the place where the common interosseous artery arises, and, after running deep to the flexor carpi radialis and through the humeral head of the flexor digitorum profundus, most of them end in the superficially lying, flattened flexor digitorum superficialis. In their path to this muscle, they lie approximately 1 cm proximal and parallel to the deep antebrachial vessels. In this deep location a branch is sent to the radial head of the flexor digitorum profundus, which it completely innervates, and smaller branches enter the humeral head of this muscle, the lateral part of which is also supplied by the ulnar nerve (Sharp et al., 1990). The small interosseous nerve of the antebrachium (n. interosseus antebrachii) first runs on the proximal part of the delicate interosseous membrane. It then perforates this membrane and runs distally on approximately the proximal half of the pronator quadratus, where it appears as a fine, white streak. It enters this muscle in its distal half and innervates it.

The portion of the median nerve that continues distad in the antebrachium, after the muscular branches have arisen, is at first related to the median artery and vein. At approximately the middle of the antebrachium, the median artery gives off the radial artery, Here, the median nerve continues distad in relation to the larger median artery (Fig. 17-18). This portion of the median nerve is small, measuring approximately 0.5 mm in diameter. The remaining branches of the median nerve will be described with the nerves to the forepaw.

The ulnar nerve (n. ulnaris) (Figs. 17-11 and 17-12) arises in close association with the radial and median nerves from the eighth cervical and the first and second thoracic nerves (Fig. 17-14). Sharp et al. (1990) determined that C-8 and T-1 contributed to the ulnar nerve in six of six dogs, C-7 in one of six, and T-2 in four of the six dogs. Of the total efferent axons in the nerve, 24% came from C-8, 65% from T-1, 11% from T-2, and fewer than 1% from C-7. Bailey et al. (1982) found that the cutaneous afferents in the ulnar nerve arose from C-8 in 10 of 10 dogs, T-1 in 10 of 10, and T-2 in 8 of 10. Mutai et al. (1986), using horseradish peroxidase, found that the ulnar nerve arose from C-8 through T-2. After leaving the caudal part of the brachial plexus, the median and ulnar nerves are flanked by the brachial artery cranially and the brachial vein caudally. They are deep to a thick layer of brachial fascia and bound to each other by areolar tissue until they reach the middle of the brachium, where they diverge. The ulnar nerve, which measures approximately 3 mm in diameter, runs distad along the cranial border of the medial head of the triceps brachii and adjacent to the caudal border of the biceps brachii. It crosses the elbow caudal to the prominent medial epicondyle. On entering the caudomedial part of the antebrachium, the ulnar nerve runs deep to the thick antebrachial fascia. After crossing caudal to the medial epicondyle of the humerus just proximal to the origin of the humeral head of the superficial digital flexor, it runs deep to the ulnar head of the flexor carpi ulnaris (Fig. 17-18). Like the median nerve, no muscular branches leave the ulnar nerve as it traverses the brachium.

The caudal cutaneous antebrachial nerve (n. cutaneus antebrachii caudalis) leaves the caudal part of the ulnar nerve near the beginning of the distal third of the brachium and passes over the medial surface of the olecranon tuber into the caudomedial part of the antebrachium (Figs. 17- 12, 17-18, and 17-20). Bailey et al. (1982) determined that this branch of the ulnar nerve arose from T-1 in 1 of 10 dogs, T-1 and T-2 in 7 of 10, and C-8, T-1, and T-2 in 1 of 10. In its subcutaneous course throughout most of the area it supplies, it is accompanied by the collateral ulnar artery and vein. It freely sends branches to the skin as it winds across the proximal portion of the antebrachium from the medial to the caudolateral aspects. Ascending branches arborize in the skin of the distal part of the brachium. The cutaneous area of the caudal cutaneous antebrachial nerve lies on the proximal two thirds of the skin of the caudolateral aspect of the antebrachium (Fig. 17-23). The cutaneous area of the lateral cutaneous antebrachial branches of the superficial radial nerve overlaps the cutaneous area of the caudal cutaneous antebrachial nerve caudolaterally, and the cutaneous area of the medial cutaneous antebrachial branch of the musculocutaneous nerve overlaps its cutaneous area caudomedially. Distally, the cutaneous area of the proximal branch of the dorsal branch of the ulnar overlaps the cutaneous area of the caudal cutaneous antebrachial nerve. This overlap is described when the innervation of the forepaw is described. The caudal cutaneous antebrachial nerve is an excellent site for testing for avulsions of the caudal roots of the spinal nerves contributing to the brachial plexus because of its origins from T-1 and T-2, and seldom from C-8 (Bailey & Kitchell, 1984).

The muscular branches (rami musculares) of the ulnar nerve, which supply the muscles of the antebrachium, are peripheral branches of a short, stout trunk that leaves the caudal side of the ulnar nerve as it passes caudal to the medial epicondyle of the humerus and plunges into the deep surface of the thin, wide ulnar head of the flexor carpi ulnaris (Fig. 17-20). The ulnar nerve, entering the septum between the ulnar and the humeral heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris, sends a branch approximately 1 mm in diameter and 1.5 cm long distally into the caudal border of the humeral head of the deep digital flexor. In the proximal fifth of the antebrachium, as the ulnar nerve curves around the caudal border of the humeral head of the flexor carpi ulnaris, it sends a stout branch into its lateral surface. Throughout the middle third of the antebrachium the ulnar nerve lies on the caudal border of the deep digital flexor, where it is covered by the humeral head of the flexor carpi ulnaris. At approximately the middle of the antebrachium, the small, cutaneous dorsal branch of the ulnar nerve arises. This branch and the palmar branch arise as terminal branches of the ulnar nerve. Both of these branches are distributed to the structures of the forepaw and are described with the nerves of the forepaw.

Both the ulnar and the median nerves supply muscles on the caudomedial side of the forearm. A summary of these muscles and their innervation is shown in Table 17-1.