Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime

Try Prime

and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

Amazon Prime members enjoy:- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new:

-12% $21.05$21.05

Ships from: Amazon Sold by: RoseBookz

Save with Used - Good

$9.30$9.30

Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Dream Books Co.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required.

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Audible sample

Audible sample Follow the authors

OK

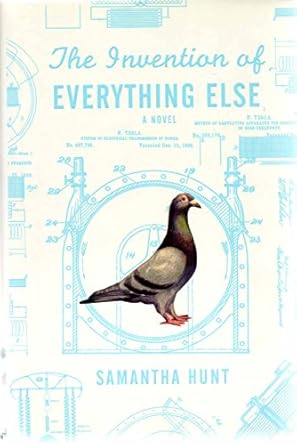

The Invention of Everything Else Hardcover – January 1, 2008

Purchase options and add-ons

- Print length257 pages

- LanguageEnglish

- PublisherMariner Books

- Publication dateJanuary 1, 2008

- Dimensions6.25 x 0.75 x 9.25 inches

- ISBN-10061880112X

- ISBN-13978-0618801121

Discover the latest buzz-worthy books, from mysteries and romance to humor and nonfiction. Explore more

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

From Publishers Weekly

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

From The New Yorker

Copyright © 2008 Click here to subscribe to The New Yorker

From Bookmarks Magazine

Copyright © 2004 Phillips & Nelson Media, Inc.

Review

“Hunt (The Seas) delivers a breathtaking novel that is both difficult to classify and impossible to ignore." Library Journal

"Oddly charming and pleasantly peculiar, Hunt’s novel offers a unique perspective on hope and imagining life’s possibilities." Booklist, ALA

“Inspires both awe and envy…Hunt seems to achieve this blend effortlessly…making it more remarkable still with her own offbeat sensibility." Bookpage

"A New York City chambermaid sparks a friendship with oddball inventor Nikola Tesla in Samantha Hunt's dazzling novel." Vanity Fair

"Sophisticated pastiche of science fiction, fantasy, melodrama, and historical anecdote...It all adds up to a precocious math of human marvel." Elle

"Former real-life scientist Nikola Tesla befriends a fictional hotel chambermaid in Samantha Hunt's ingenious work of historical fiction." Marie Claire

"Hunt's magical new novel is a love letter to one of the world's most remarkable inventors…For a moment…everything seems possible." The Washington Post

“[Hunt] puts her considerable talents to work…Tesla's story…is crafted with an intensity...that makes the heart beat faster.” Los Angeles Times

"Full of vivid imagery, sounds, memories…this novel is a sweet story of just how normal it is to be different." Boston Globe

“Hunt's history-steeped tale…reminds us that science necessitates creativity, which also, of course, is the essence of literature." The San Francisco Chronicle

"In her vivid reimagining…Hunt pursues the links between science and creativity and storytelling and invention to their logical extreme.” New York Magazine

“Glorious…pages of prose: daring and delicious, perfectly calibrated, fresh but not raw, original but neither off-putting nor disconcertingly strange." The Chicago Tribune

“[INVENTION is] a smart, colorful novel about aspiration and wish fulfillment in a world…engineers can’t control." - The Believer

"Hunt's fascination with language is unmistakable, resulting in beautiful, intimate observations . . . elegant, inspired." The Village Voice

"Marvelous…one wishes these scenes would never end…[it] takes its readers back to a kindler, gentler New York.” - LA Weekly

"Hunt weaves the stranger-than-fiction facts…into an engaging novel…that crackles with the possibility and promise of scientific innovation." - Seed

"An electrified, magnetized concoction that pleases, teases and dazzles…takeoff soaring with her, you will not be disappointed..." - The Oregonian

”The author is rapturous, vividly in love with her subjects and her characters." - New York Observer

"[Hunt’s] novel might be 2008's 'Special Topics in Calamity Physics'…soulful and scientific at the same time." - Velocity Weekly

“Hunt weaves history and imagination to create a seductively original world…” -- Heidi Julavits, author of The Uses of Enchantment

“A highwire performance by a soulful and wildly intelligent writer.” -- Rene Steinke, author of the NBA-nominated Holy Skirts

“You hold in your hands an important, fun, educational, magic read." -- Darin Strauss, author of Chang and Eng

About the Author

From The Washington Post

Reviewed by Ron Charles

Samantha Hunt's magical new novel is a love letter to one of the world's most remarkable inventors. You may never have heard of Nikola Tesla, but he briefly outshone Edison and Westinghouse, and from the moment you wake up in the morning, you depend on devices made possible by his revolutionary work with electricity. Tesla was born in Serbia in 1856, and his life followed a rags-to-riches-to-rags trajectory that would sound melodramatic if it weren't so tragic and true -- or told with such surprising charm in The Invention of Everything Else.

This melancholy romance begins on the first day of 1943, in the New Yorker hotel, once the tallest building in the city. It rises up in these pages in all its mysterious grandeur, a lighter version of the surreal hotel in Steven Millhauser's Martin Dressler (1996). Impoverished by a series of disastrous financial dealings, Tesla has been holed up here with his notes and unpaid bills for 10 years. He's talking to himself or to his beloved pigeon. His reputation has been eclipsed by other inventors (some of them thieves) and derided by the popular press. (Superman battles a mad scientist named Tesla.) There are rumors that he believes he's receiving messages from Mars, that he's building a death ray, that he's working on a time machine.

Indeed, the novel is something of a time machine itself, and not just because of its lyrical recreation of New York in the first half of the 20th century. The story is a Rube Goldberg contraption of history, slapstick, biography and science fiction: a narrative bricolage that looks too precarious to work but is too alluring to resist.

Holding it all together is a young woman named Louisa who works as a maid at the New Yorker. She "imagines herself a small but necessary part of the glimmering hotel," which employs 2,000 people. She's "a sharp city girl, frank, skeptical, and wise, with a desperate weakness for corny radio tales." She lives with her widowed father, a night watchman at the public library, and those lurid radio stories provide the only drama in her life. But they also fire her imagination about "her alter ego, part chambermaid, part detective."

During a blackout on New Year's Day, she notices a brilliant light coming from under the door of a double suite on the 33rd floor. "Someone in that room," she realizes, "has stolen all the electricity." And so begins a touching friendship between an 87-year-old inventor in the final weeks of his life and a 24-year-old woman whose life is about to begin.

A few subplots veer off like sparks -- more eye-catching than illuminating. There are ominous hints of a secret government investigation of Tesla. Other chapters describe his remarkable childhood, his early breakthroughs with alternating current, his bitter rivalry with Edison, his descent into a figure of public ridicule. Hunt throws in stranger-than-fiction anecdotes about the opening of the New York Public Library, the development of the electric chair, and Tesla's efforts to harness lightning and project it around the world. In the novel's present tense, Louisa meets a handsome stranger who seems to have come from the future. And her father becomes convinced that a friend's machine can take him back to see his dead wife.

I realize all this sounds hopelessly scrambled and silly, but Hunt moves through these engaging episodes with a voice that's at once smart and whimsical. And we can't help sharing Louisa's tender regard for Tesla. There's something incongruously vulnerable about this genius who hoped to harness the invisible fluid of the universe. Hunt peers into his childhood for the roots of his loneliness. He's certain that "love is impossible," yet spends his life trying to bring about a "future where human beings have wings and electricity is miraculous and free."

Hunt has so gracefully mingled outlandish fact with outlandish fiction that it's difficult to know where one begins and the other ends, but it's a delightful homage to the scientist who tells Louisa, "I want to be believed." For a moment, in these pages, everything seems possible.

Copyright 2008, The Washington Post. All Rights Reserved.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Things like that, talking storms, happen to me frequently. Take for example the dust here in my hotel room. Each particle says something as it drifts through the last rays of sunlight, pale blades that have cut their way past my closed curtains. Look at this dust. It is everywhere.

Here is the tiniest bit of a woman from Bath Beach who had her hair styled two days ago, loosening a few small flakes of scalp in the process.

Two days it took her to arrive, but here she is at last. She had to come because the hotel where I live is like the sticky tongue of a frog jutting out high above Manhattan, collecting the city particle by wandering particle. Here is some chimney ash. Here is some buckwheat flour blown in from a Portuguese bakery on Minetta Lane and a pellicle of curled felt belonging to the haberdashery around the corner.

Here is a speck of evidence from a shy graft inspector. Maybe he lived in the borough of Queens. Maybe a respiratory influenza killed him off in 1897. So many maybes, and yet he is still here. And, of course, so am I. Nikola Tesla, Serbian, world-famous inventor, once celebrated, once visited by kings, authors and artists, welterweight pugilists, scientists of all stripes, journalists with their prestigious awards, ambassadors, mezzo-sopranos, and ballerinas. And I would shout down to the dining hall captain for a feast to be assembled. Quickly! Bring us the Stuffed Saddle of Spring Lamb. Bring us the Mousse of Lemon Sole and the Shad Roe Belle Meunicre! Potatoes Raclette! String Bean Sauté! Macadamia nuts! A nice bourbon, some tonic, some pear nectar, coffees, teas, and please, please make it fast!” That was some time ago. Now, more regularly, no one visits. I sip at my vegetable broth listening for a knock on the door or even footsteps approaching down the hallway. Most often it turns out to be a chambermaid on her rounds. I’ve been forgotten here. Left alone talking to lightning storms, studying the mysterious patterns the dust of dead people makes as it floats through the last light of day.

Now that I have lived in the Hotel New Yorker far longer than any of the tourists or businessmen in town for a meeting, the homogeneity of my room, a quality most important to any hotel décor, has all but worn off. Ten years ago, when I first moved in, I constructed a wall of shelves. It still spans floor to ceiling. The wall consists of seventy-seven fifteen-inch-tall drawers as well as a number of smaller cubbyholes to fill up the odd spaces. The top drawers are so high off the ground that even I, at over six feet tall, am forced to keep a wooden step stool behind the closet door to access them. Each drawer is stained a deep brown and is differentiated from the others by a small card of identification taped to the front. The labels have yellowed under the adhesive. COPPER WIRE. CORRESPONDENCE. MAGNETS. PERPETUAL MOTION. MISC.

Drawer #42. It sticks and creaks with the weather. This is the drawer where I once thought I’d keep all my best ideas. It contains only some cracked peanut shells. It is too dangerous to write my best ideas down. Whoops. Wrong drawer. Whoops.” I repeat the word. It’s one of my favorites. If it were possible I’d store Whoops” in the safe by my bed, along with OK” and Sure thing” and the documents that prove that I am officially an American citizen.

Drawer #53 is empty, though inside I detect the slightest odor of ozone. I sniff the drawer, inhaling deeply. Ozone is not what I am looking for. I close #53 and open #26. Inside there is a press clipping, something somebody once said about my work: Humanity will be like an antheap stirred up with a stick. See the excitement coming!” The excitement, apparently, already came and went.

That is not what I’m looking for.

Somewhere in one of the seventy-seven drawers I have a clipping from an article published in the New York Times. The article includes a photo of the inventor Guglielmo Marconi riding on the shoulders of men, a loose white scarf held in his raised left hand, flagging the breeze. All day thoughts of Marconi have been poking me in the ribs. They often do whenever I feel particularly low or lonely or poorly financed. I’ll shut my eyes and concentrate on sending Marconi a message. The message is, Marconi, you are a thief.” I focus with great conceentration until I can mentally access the radio waves. As the invisible waves advance through my head I attach a few words to each donkey,” and worm,” and limacine,” which is an adjective that I only recently acquired the meaning of, like a slug. When I’m certain that the words are fixed to the radio waves I’ll send the words off toward Marconi, because he has stolen my patents. He has stolen my invention of radio. He has stolen my notoriety. Not that either of us deserved it. Invention is nothing a man can own.

And so I am resigned.

Out the window to the ledge, thirty-three stories above the street, I go legs first. This is no small feat. I am no small man. Imagine an oversized skeleton. I have to wonder what a skeleton that fell thirty-three stories, down to the street below, would look like. I take one tentative glance toward the ground. Years ago power lines would have stretched across the block in a mad cobweb, a net, because years ago, any company that wanted to provide New York with electricity simply strung its own decentralized power lines all about the city before promptly going out of business or getting forced out by J. P. Morgan. But now there is no net. The power lines have been hidden underground.

That’s not why I’ve come here. I have no interest in jumping. I’m not resigned to die. Most certainly not. No, I’m resigned only to leave humans to their humanness. Die? No. Indeed, I’ve always planned to see the far side of one hundred and twenty-five. I’m only eighty-six. I’ve got thirty-nine more years. At least.

HooEEEhoo. HooEEEhoo.” The birds answer the call. Gray flight surrounds me, and the reverse swing of so many pairs of wings, some iridescent, some a bit duller, makes me dizzy. The birds slow to a landing before me, beside me, one or two perching directly on top of my shoulders and head. Mesmerized by their feathers such engineering! I lose my balance. The ledge is perhaps only forty-five centimeters wide. My shoulders lurch forward a bit, just enough to notice the terrific solidity of the sidewalks thirty-three stories down. Like a gasp for air, I pin my back into the cold stone of the window’s casing.

A few pigeons startle and fly away out over Eighth Avenue, across Manhattan. Catching my breath, I watch them go. I watch them disregard gravity, the ground, and the distance between us. And though an old feeling, one of wings, haunts my shoulder blades, I stay pinned to the window. I’ve learned that I cannot go with them.

Out on the ledge of my room, I maintain a small infirmary for injured and geriatric pigeons. A few tattered boxes, some shredded newspaper. One new arrival hobbles on a foot that has been twisted into an angry knuckle, a pink stump. I see she wants nothing more to do with the hydrogen peroxide that bubbled fiercely in her wound last night. I let her be, squatting instead to finger the underside of another bird’s wing. Beneath his sling the ball of his joint has finally stayed lodged in its orbit, and for this I am relieved. I turn my attention to mashing meal.

Hello, dears.” The air of New York this high up smells gray with just a hint of blue. I sniff the air. It’s getting chilly, hmm?” I ask the birds. And what are your plans for the New Year tonight?” The hotel has been in a furor, preparing for the festivities all week. The birds say nothing. No plans yet? No, me neither.” I stand, looking out into the darkening air. HooEEEhoo?” It’s a question. I stare up into the sky, wondering if she will show tonight. HooEEEhoo?” Having lived in America for fifty-nine years, I’ve nearly perfected my relationships with the pigeons, the sparrows, and the starlings of New York City. Particularly the pigeons. Humans remain a far greater challenge.

I sit on the ledge with the birds for a long while, waiting for her to appear. It is getting quite cold. As the last rays of sun disappear from the sky, the undersides of the clouds glow with a memory of the light. Then they don’t anymore, and what was once clear becomes less so in the darkening sky. The bricks and stones of the surrounding buildings take on a deeper hue. A bird cuts across the periphery of my sight. I don’t allow myself to believe it might be her. HooEEEhoo?” Don’t look, I caution my heart. It won’t be her. I take a look just the same. A gorgeous checkered, his hackle purple and green. It’s not her.

She is pale gray with white-tipped wings, and into her ear I have whispered all my doubts. Through the years I’ve told her of my childhood, the books I read, a history of Serbian battle songs, dreams of earthquakes, endless meals and islands, inventions, lost notions, love, architecture, poetry a bit of everything. We’ve been together since I don’t remember when. A long while. Though it makes no sense, I think of her as my wife, or at least something like a wife, inasmuch as any inventor could ever have a wife, inasmuch as a bird who can fly could ever love a man who can’t.

Most regularly she allows me to smooth the top of her head and neck with my pointer finger. She even encourages it. I’ll run my finger over her feathers and feel the small bones of her head, the delicate cage made of calcium built to protect the bit of magnetite she keeps inside. This miraculous mineral powers my system of alternating-current electrical distribution. It also gives these birds direction, pulling north, creating a compass in their bodies, ensuring that they always know the way home.

I’ve not seen my own home in thirty-five years. There is no home anymore. Everyone is gone. My poor, torn town of Smiljan in what was once Lika, then Croatia, now Yugoslavia. I don’t have wings,” I tell the birds who are perched beside me on the ledge. I don’t have magnetite in my head.” These deficiencies punish me daily, particularly as I get older and recall Smiljan with increasing frequency.

When I was a child I had a tiny laboratory that I’d constructed in an alcove of trees. I nailed tin candle sconces to the trunks so that I could work into the night while the candles’ glow crept up the orange bark and filled my laboratory with odd shadows the stretched fingers of pine needles as they shifted and grew in the wind.

There is one invention from that time, one of my very first, that serves as a measure for how the purity of thought can dwindle with age. Once I was clever. Once I was seven years old. The invention came to me like this: Smiljan is a very tiny town surrounded by mountains and rivers and trees. My house was part of a farm where we raised animals and grew vegetables. Beside our home was a church where my father was the minister. In this circumscribed natural setting my ears were attuned to a different species of sounds: footsteps approaching on a dirt path, raindrops falling on the hot back of a horse, leaves browning. One night, from outside my bedroom window, I heard a terrific buzzing noise, the rumble of a thousand insect wings beating in concert. I recognized the noise immediately. It signaled the seasonal return of what people in Smiljan called May bugs, what people in America call June bugs. The insects’ motions, their constant energy, kept me awake through the night, considering, plotting, and scheming. I roiled in my bed with the possibility these insects presented.

Finally, just before the sun rose, I sneaked outside while my family slept. I carried a glass jar my mother usually used for storing stewed vegetables. The jar was nearly as large as my rib cage. I removed my shoes the ground was still damp. I walked barefoot through the paths of town, stopping at every low tree and shrub, the leaves of which were alive with June bugs. Their brown bodies hummed and crawled in masses. They made my job of collection quite easy. I harvested the beetle crop, sometimes collecting as many as ten insects per leaf. The bugs’ shells made a hard click when they struck against the glass or against another bug. So plentiful was the supply that the jar was filled to brimming in no time.

I returned to my pine-tree laboratory and set to work. First, by constructing a simple system of gear wheels, I made an engine in need of a power supply. I then studied the insects in the jar and selected those that demonstrated the most aggressive and muscular tendencies. With a dab of glue on their thorax undersides, I stuck my eight strongest beetles to the wheel and stepped back. The glue was good; they could not escape its harness. I waited a moment, and in that moment my thoughts grew dark. Perhaps, I thought, the insects were in shock. I pleaded with the bugs, Fly away!” Nothing. I tickled them with a twig. Nothing. I stomped my small feet in frustration and stepped back prepared to leave the laboratory and hide away from the failed experiment in the fronds of breakfast, when, just then, the engine began to turn. Slowly at first, like a giant waking up, but once the insects understood that they were in this struggle together their speed increased. I gave a jump of triumph and was immediately struck by a vision of the future in which humans would exist in a kingdom of ease, the burden of all our chores and travails would be borne by the world of insects. I was certain that this draft of the future would come to pass. The engine spun with a whirling noise. It was brilliant, and for a few moments I burned with this brilliance.

In the time it took me to complete my invention the world around me had woken up. I could hear the farm animals. I could hear people speaking, beginning their daily work. I thought how glad my mother would be when I told her that she’d no longer have to milk the goats and cows, as I was developing a system where insects would take care of all that. This was the thought I was tumbling joyfully in when Vuk, a boy who was a few years older than me, entered into the laboratory. Vuk was the urchin son of an army officer. He was no friend of mine but rather one of the older children in town who, when bored, enjoyed needling me, vandalizing the laboratory I had built in the trees. But that morning my delight was such that I was glad to see even Vuk. I was glad for a witness. Quickly I explained to him how I had just revolutionized the future, how I had developed insect energy, the source that would soon be providing the world with cheap, replenishable power. Vuk listened, glancing once or twice at the June bug engine, which, by that time, was spinning at a very impressive speed. His envy was thick; I could nearly touch it. He kept his eyes focused on the glass jar that was still quite full of my power source. Vuk twisted his face up to a cruel squint. He curled the corners of his fat lips. With my lecture finished, he nodded and approached the jar. Unscrewing the lid he eyed me, as though daring me to stop him. Vuk sank his hand, his filthy fingernails, down into the mass of our great future and withdrew a fistful of beetles. Before I could even understand the annihilation I was about to behold, Vuk raised his arm to his mouth, opened the horrid orifice, and began to chew. A crunching sound I will never forget ensued. Tiny exoskeletons mashed between molars, dark legs squirming for life against his chubby white chin. With my great scheme crashing to a barbarous end I could never look at a June bug again I ran behind the nearest pine tree and promptly vomited.

On the ledge the birds are making a noise that sounds like contentment, like the purr of the ocean from a distance. I forget Vuk. I forget all thoughts of humans. I even forget about what I was searching for in the wall of drawers until, staring out at the sky, I don’t forget anymore.

On December 12, 1901, Marconi sent a message across the sea. The message was simple. The message was the letter S. The message traveled from Cornwall, England, to Newfoundland, Canada. This S traveled on air, without wires, passing directly through mountains and buildings and trees, so that the world thought wonders might never cease. And it was true. It was a magnificent moment. Imagine, a letter across the ocean without wires.

But a more important date is October 1893, eight years earlier. The young Marconi was seated in a crowded café huddled over, intently reading a widely published and translated article written by me, Nikola Tesla. In the article I revealed in exacting detail my system for both wireless transmission of messages and the wireless transmission of energy. Marconi scribbled furiously.

I pet one bird to keep the chill from my hands. The skin of my knee is visible through my old suit. I am broke. I have given AC electricity to the world. I have given radar, remote control, and radio to the world, and because I asked for nothing in return, nothing is exactly what I got. And yet Marconi took credit. Marconi surrounded himself with fame, strutting as if he owned the invisible waves circling the globe.

Quite honestly, radio is a nuisance. I know. I’m its father. I never listen to it. The radio is a distraction that keeps one from concentrating.

HooEEEhoo?” There is no answer.

I’ll have to go find her. It is getting dark and Bryant Park is not as close as it once was, but I won’t rest tonight if I don’t see her. Legs first, I reenter the hotel, and armed with a small bag of peanuts, I set off for the park where my love often lives. The walk is a slow one, as the streets are beginning to fill with New Year’s Eve revelers. I try to hurry, but the sidewalks are busy with booby traps. One gentleman stops to blow his nose into a filthy handkerchief, and I dodge to the left, where a woman tilts her head back in a laugh. Her pearl earrings catch my eye. Just the sight of those monstrous jewels sets my teeth on edge, as if my jaws were being ground down to dull nubs. Through this obstacle course I try to outrun thoughts of Marconi. I try to outrun the question that repeats and repeats in my head, paced to strike with every new square of sidewalk I step on. The question is this: If they are your patents, Niko, why did Marconi get word well, not word but letter why did he get a letter across the ocean before you?” I walk quickly. I nearly run. Germs be damned. I glance over my shoulder to see if the question is following.

I hope I have outpaced it.

New York’s streets wend their way between the arched skyscrapers. Most of the street-level businesses have closed their doors for the evening. Barbizon Hosiery. Conte’s Salumeria, where a huge tomcat protects the drying sausages. Santangelo’s Stationery and Tobacco. Wasserstein’s Shoes. Jung’s Nautical Maps and Prints. The Wadesmith Department Store. All of them closed for the holiday. My heels click on the sidewalks, picking up speed, picking up a panic. I do not want this question to catch me, and worse, I do not want the answer to this question to catch me. I glance behind myself one more time. I have to find her tonight.

I turn one corner and the question is there, waiting, smoking, reading the newspaper. I pass a lunch counter and see the question sitting alone, slurping from a bowl of chicken soup. If they are your patents, Niko, why did Marconi send a wireless letter across the ocean before you?” The question makes me itch. I decide to focus my thoughts on a new project, one that will distract me. As I head north, I develop an appendix of words that begin with the letter S, words that Marconi’s first wireless message stood for.

1. saber-toothed 2. sabotage 3. sacrilege 4. sad 5. salacious 6. salesman 7. saliva 8. sallow 9. sanguinary 10. sap 11. sarcoma 12. sardonic 13. savage 14. savorless 15. scab 16. scabies 17. scalawag 18. scald 19. scandal 20. scant 21. scar 22. scarce 23. scary 24. scatology 25. scorn 26. scorpion 27. scourge 28. scrappy 29. screaming 30. screed 31. screwball 32. scrooge 33. scrupulousness 34. scuffle 35. scum 36. scurvy 37. seizure 38. selfish 39. serf 40. sewer 41. shabby 42. shady 43. sham 44. shameless 45. shark 46. shifty 47. sick 48. siege 49. sinful 50. sinking 51. skewed 52. skunk 53. slander 54. slaughter 55. sleaze 56. slink 57. slobber 58. sloth 59. slug 60. slur 61. smear 62. smile 63. snake 64. sneak 65. soulless 66. spurn 67. stab 68. stain 69. stale 70. steal 71. stolen 72. stop stop stop.

Marconi is not the one to blame. But if he isn’t, I have to wonder who is.

About ten years ago Bryant Park was redesigned. Its curves were cut into straight lines and rimmed with perennial flower beds. Years before that a reservoir, one with fifty-foot-high walls, sat off to the east, filled with silent, still water as if it were a minor sea in the middle of New York City. As I cross into the park I feel cold. I feel shaky. I feel as if it is the old reservoir and not the park that I am walking into. My chest is constricted by the pressure of this question, by this much water. I look for her overhead, straining to collect the last navy light in the sky. Any attempt to swim to the surface is thwarted by a weakness in my knees, by Why did Marconi get all the credit for inventing radio?” The reservoir’s been gone for years. Still, I kick my legs for the surface. My muscles feel wooden and rotten. I am only eighty- six. When did my body become old? My legs shake. I am embarrassed for my knees. If she won’t come tonight the answer will be all too clear. Marconi took the credit because I didn’t. Yes, I invented radio, but what good is an invention that exists only in one’s head?

I manage a HooEEEhoo?” and wait, floating until, through the water overhead, there’s a ripple, a white-tipped flutter. HooEEEhoo! HooEEEhoo!” The sight of her opens a door, lets in the light, and I’m left standing on the dry land of Bryant Park. She is here. I take a deep breath. The park is still and peaceful. She lands on top of Goethe’s head. Goethe, cast here in bronze, does not seem to mind the intrusion of her gentle step.

We’re alone. My tongue is knotted, unsure how to begin. My heart catches fire. I watched for you at the hotel,” I say.

She does not answer but stares at me with one orange eye, an eye that remembers me before all this gray hair set in, back when I was a beauty too. Sometimes it starts like this between us. Sometimes I can’t hear her. I take a seat on a nearby bench. I’ll have to concentrate. On top of Goethe’s head she looks like a brilliant idea. Her breast is puffed with breath. Agitation makes it hard to hear what she is saying.

Perhaps you would like some peanuts?” I ask, removing the bag from my pocket. I spread some of the nut meats out carefully along the base of the statue before sitting back down.

She is here. I will be fine. The air is rich with her exhalations. It calms me. I’m OK even when I notice that the question has slithered out of the bushes. It has settled down on the bench beside me, less a menace now, more like an irritating companion I long ago grew used to. I still my mind to hers and then I can hear.

Niko, who is your friend?” she asks.

I turn toward it. The question has filled the bench beside me, spilling over into my space, squashing up against my thigh. The question presents itself to her. If they were Nikola’s patents, why did Marconi get all the credit for inventing the radio?” Hmm,” she says. That’s a very good question indeed.” She fluffs her wings into flight, lowering herself from Goethe’s head, over the point of his tremendous nose, down to where I’d spread a small supper for her. She begins to eat, carefully pecking into one peanut. She lifts her head. The manifestation of precision. There are many answers to that question, but what do you think, Niko?” It seems so simple in front of her. I suppose I allowed it to happen,” I say, finally able to bear this truth now that she is here. At the time I couldn’t waste months, years, developing an idea I already knew would work. I had other projects I had to consider.” Yes, you’ve always been good at considering,” she says. It’s carrying an idea to fruition that is your stumbling block. And the world requires proof of genius inventions. I suppose you know that now.” She is strolling the pedestal’s base. I notice a slight hesitation to her walk. Are you feeling all right?” I ask.

I’m fine.” She turns to face me, changing the subject back to me. Then there is the matter of money.” Yes. I’ve never wanted to believe that invention requires money but have found lately that good ideas are very hard to eat.” She smiles at this. You could have been a rich man seventy times over,” she reminds me.

Yes,” I say. It’s true.

You wanted your freedom instead. I would not suffer interference from any experts,’ is how you put it.” And then it is my turn to smile. But really.” I lean forward. Who can own the invisible waves traveling through the air?” Yes. And yet, somehow, plenty of people own intangible things all the time.” Things that belong to all of us! To no one! Marconi,” I spit as if to remind her, will never be half the inventor I am.” She ruffles her feathers and stares without blinking. I tuck my head in an attempt to undo my statement, my bluster.

Marconi,” she reminds me, has been dead for six years.” She stares again with a blank eye, and so I try, for her sake, to envision Marconi in situations of nobility. Situations where, for example, Marconi is being kind to children or caring for an aging parent. I try to imagine Marconi stopping to admire a field of purple cow vetch in bloom. Marconi stoops, smells, smiles, but in every imagining I see his left hand held high, like victory, a white scarf fluttering in the breeze.

Please,” she finally says. Not this old story, darling.” Her eye remains unblinking. She speaks to me and it’s like thunder, like lightning that burns to ash my bitter thoughts of Marconi.

Bryant Park seems to have fallen into my dream. We are alone, the question having slithered off in light of its answer. She finishes her meal while I watch my breath become visible in the dropping temperature.

It’s getting cold,” I tell her.

Yes.” Perhaps you should come back to the hotel. I can make you your own box on the sill. It will be warmer there. It’s New Year’s Eve.” She stops to consider this. She doesn’t usually like the other birds that hang around my windowsill.

Please. I worry.” Hmm.” She considers it.

Come back to the hotel with me.” Excuse me?” a deep male voice answers. Not hers.

I look up. Before me is a beat cop. His head is nearly as large as Goethe’s bronze one. His shoulders are as broad as three of me. He carries a nightstick, and seeing no other humans around, he seems to imagine that I am addressing him. The thought makes me laugh.

Any human passing by would think that I am sitting alone in the park at night, talking to myself. This is precisely my problem with so many humans. Their hearing, their sight, all their senses, have been dulled to receive information on such limited frequencies. I muster a bit of courage. Do we not look into each other’s eyes and all in you is surging, to your head and heart, and weaves in timeless mystery, unseeable, yet seen, around you?” What in God’s name are you talking about?” the policeman asks.

Goethe,” I say, motioning to the statue behind him.

Well, Goethe yourself on home now, old man. It’s late and it’s cold.

You’ll catch your death here.” She is still perched on one corner of the bust’s pedestal. Old man. Karl Fischer cast the head in 1832; then the Goethe Club here in New York took it for a bit until they sent it off to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The museum didn’t have much use for it, so they donated” it to Bryant Park a few years ago. Goethe’s head has been shuffled off nearly as many times as I have.

I know how you feel,” I tell the head.

Goethe stays quiet.

Come on, old-timer,” the policeman says, reaching down to grab my forearm. It seems I am to be escorted from the park.

This clown’s got no idea who I am,” I say to her. He thinks I’m a vagrant.” She looks at me as if taking a measure. She alone cuts through the layers of years and what they’ve done. She is proud of me. Why don’t you just tell him?” she asks. You invented radio and alternating current.” Goethe finally speaks up. Oh, yes,” he says. I’m sure he’d believe you.” The policeman can’t hear either of them. Even if he could, Goethe is right this officer would never believe a word of it. You’re the King of England, I suppose,” the cop says. We get about ten King of Englands in here every week.” The cop has his bear paws latched around my forearm and is steering me straight out of the park. Resistance, I have a strong feeling, would prove ineffective.

Are you coming?” I ask her, but when I look back at the pedestal, she is gone. The solidity of the police officer’s grip is the one certainty.

She has flown away, taking all of what I know with her the Hotel New Yorker, Smiljan, the pigeons, my life as a famous inventor.

* * * * * *

You already asked me that question.

Yes, but we are just trying to be sure. Now, you have said that you have no memory of your activities on January 4th, and yet you have also said that you are certain you did not visit with Mr. Nicola Tesla, who was at that time a guest in your hotel. What we wonder is, how can you be certain you did not visit with him when you say you can’t remember what you did?

I see.

Why don’t you just tell us what you remember.

Mr. Tesla didn’t do anything wrong.

Why don’t you just tell us what you remember.

Copyright (c) 2008 by Samantha Hunt. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Company.

Product details

- Publisher : Mariner Books; First Edition (January 1, 2008)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 257 pages

- ISBN-10 : 061880112X

- ISBN-13 : 978-0618801121

- Item Weight : 1.1 pounds

- Dimensions : 6.25 x 0.75 x 9.25 inches

- Best Sellers Rank: #555,224 in Books (See Top 100 in Books)

- #5,174 in Contemporary Literature & Fiction

- #29,221 in American Literature (Books)

- #36,970 in Historical Fiction (Books)

- Customer Reviews:

About the authors

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read book recommendations and more.

Samantha Hunt’s novel, Mr. Splitfoot, is about orphans who talk to the dead. It connects con artists, mothers and meteors in a subversive ghost story. The Dark Dark, Hunt's first collection of short stories, maps fear of the night. Hunt’s second book, The Invention of Everything Else, a novel about inventor Nikola Tesla, was a finalist for the Orange Prize and winner of the Bard Fiction Prize. Her first novel, The Seas, won a National Book Foundation award for writers under thirty-five. Hunt’s fiction has been published in The New Yorker, McSweeney's, Tin House, the New York Times and a number of other fine publications.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Learn more how customers reviews work on AmazonCustomers say

Customers find the storytelling fantastical and engaging. They describe the pacing as fast and the characters as talented and wise beyond their years. The book is described as an excellent, great read with clever writing and poetry. Readers enjoy the parts written from Tesla's perspective and the author's insights.

AI-generated from the text of customer reviews

Customers enjoy the storytelling. They find it fascinating, enchanting, and entertaining. The story provides a rare glimpse into the world with its unusual structure and descriptions mixed with human emotion. Readers appreciate the eccentric, haunting, and mysterious characters.

"...Those scenes are marvelous. Tesla is wonderfully portrayed as eccentric, a bit scary yet fascinating, mysterious, wise, witty, sad and a little..." Read more

"...The story provides a rare, fascinating and highly entertaining glimpse into the life and times of someone who is perhaps the most misunderstood..." Read more

"...I LOVED the story up til then. Obviously I was fairly certain that Tesla would die toward the end given the book opens on New Years 1943...." Read more

"Great subject matter. Intrigue and poetry. I appreciated the descriptions mixed with human emotion. Cleverly crafted, cleverly written, great read." Read more

Customers enjoy the pacing and find the book entertaining. They appreciate the talented and wise characters, including Hunt and Tesla. The story blends facts and fiction well, providing an engaging read with wonderful scenes.

"...Tesla is wonderfully portrayed as eccentric, a bit scary yet fascinating, mysterious, wise, witty, sad and a little bitter, yet noble and resigned...." Read more

"...The story provides a rare, fascinating and highly entertaining glimpse into the life and times of someone who is perhaps the most misunderstood..." Read more

"...I appreciated the descriptions mixed with human emotion. Cleverly crafted, cleverly written, great read." Read more

"...This book brings to light Tesla's brilliance and achievements, most of which many never knew about...." Read more

Customers like the book's readability. They find it an excellent, fascinating, and entertaining glimpse into someone's life.

"This is the best book I’ve read so far this year. An excellent read and a story that will keep you thinking about it long after it’s finished." Read more

"...The story provides a rare, fascinating and highly entertaining glimpse into the life and times of someone who is perhaps the most misunderstood..." Read more

"...Cleverly crafted, cleverly written, great read." Read more

"Enjoyed the book once I finally got into it but it took some time. The beginning of the book did not impress me as much as the rest of it...." Read more

Customers find the writing style clever and witty. They appreciate the parts written from Tesla's perspective, as well as the author's insights and thoughts.

"...portrayed as eccentric, a bit scary yet fascinating, mysterious, wise, witty, sad and a little bitter, yet noble and resigned...." Read more

"...I did very much enjoy the parts written from Tesla's POV, some of the author's insights and thought processes were brilliant, and the relationship..." Read more

"Great subject matter. Intrigue and poetry. I appreciated the descriptions mixed with human emotion. Cleverly crafted, cleverly written, great read." Read more

"...Hunt’s prose is high-quality, but this is definitely the work of a talented author who has not really come into her own yet and was too frustrating..." Read more

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. Please try again later.

- Reviewed in the United States on May 30, 2024This is the best book I’ve read so far this year. An excellent read and a story that will keep you thinking about it long after it’s finished.

- Reviewed in the United States on April 28, 2014I first learned about Tesla last July, at the age of 62. Why were we not taught about this important inventor in grade school? Ever since I learned about him, it became an obsession...I read a bunch of biographies, and then I wanted to read every fictional book about him. This was not a very long list: Tesla is still almost unknown.

Others have summarized the plot of this book, so I won't go into that. This writer's style reminds me of Anne Tyler, with her portrayals of unusual characters and their off-kilter family lives. The surrealism is heightened by the author's unusual structural choices. Occasionally the storyline jumps into the past, and segues into Tesla's journalistic recollections of his own life. Further surreal touches are brought in with a section describing Edison's electrocution of animals and his invention of the electric chair. (Yes, Edison really was an evil and unscrupulous fellow, but TIME Magazine still sells the Edison special, and they have never done a Tesla special...go figure.) The sections written from Tesla's viewpoint are in first-person, while all the rest is third. Certainly not how they tell you to structure a novel in 'writers workshop'!

Louisa was an engaging character, but the entire subplot about Louisa's father, Azor and Arthur, and the "time machine" weren't that interesting to me. Louisa's relationship with Arthur just didn't come alive. Other reviewers said "he may have come from the future", I didn't pick up on that. He was just a sort of wooden, blank character. I wish the entire book had been about Louisa's conversations and interactions with Tesla and his pigeons. Those scenes are marvelous. Tesla is wonderfully portrayed as eccentric, a bit scary yet fascinating, mysterious, wise, witty, sad and a little bitter, yet noble and resigned. I have read descriptions of the elder Tesla as physically frail, yet possessing a presence and a dignity that dominated any gathering. This novel captured that quality for me! Oh, if only I had that Time Machine, so I could go back and meet Tesla!

- Reviewed in the United States on February 29, 2008The author is able to blend enchantment with realism and history in a book that is a pure delight to read. The story provides a rare, fascinating and highly entertaining glimpse into the life and times of someone who is perhaps the most misunderstood genius of all time. What more can I say? Hunt seems to be talented and wise beyond her years. I can only add a resounding 'Bravo' for such a small gem of a book.

- Reviewed in the United States on October 29, 2014It was five stars all the way, until the very last chapter or so. I LOVED the story up til then. Obviously I was fairly certain that Tesla would die toward the end given the book opens on New Years 1943. However, the whole side plot with the "time machine" and the death of Walter and Azor was an unnecessary complication and just left the book with a more depressing tone than necessary. I did very much enjoy the parts written from Tesla's POV, some of the author's insights and thought processes were brilliant, and the relationship with Samuel Clemens, as well as Robert and Katharine Johnson, were excellent. Overall, I would recommend this book, but not with the same enthusiasm I had before finishing it...

- Reviewed in the United States on March 26, 2022Great subject matter. Intrigue and poetry. I appreciated the descriptions mixed with human emotion. Cleverly crafted, cleverly written, great read.

- Reviewed in the United States on February 5, 2013The more I read, the more I found that the brilliant mind of Nikola Tesla, his patents and inventions had been lost to other historical names we've all learned about as brilliant inventors or wealthy philanthropists. Names like Morgan, Edison and Marconi for example, have all exploited Tesla and benefitted greatly in fame and monitary rewards at Tesla's expense.

This book brings to light Tesla's brilliance and achievements, most of which many never knew about.

I believe that anyone wondering how we got to where we are and where we got the technologies we now take for granted, owes it to themselves to read this book and any other books on the man, as well watch the Tesla episode on the History Channel.

- Reviewed in the United States on November 12, 2016Enjoyed the book once I finally got into it but it took some time. The beginning of the book did not impress me as much as the rest of it. I still feel it's a worthwhile read.

- Reviewed in the United States on August 1, 2022I must have gotten a whole different book than the folks who gave this high marks. I got about 1/3 of the way through and gave up. There was very, very little about Tesla and even less about his discoveries in the 30% of the book I struggled through. I dragged myself through detailed narratives about many semi-related and even more quite unrelated characters. I was in the middle of reading about a radio broadcast that had nothing to do with Tesla or any of the gratuitously-included unrelated characters when I said to myself "Why am I doing this to myself?" And my self said, "I've wondered the same thing," and so I quit.

Top reviews from other countries

Malcolm K. MillerReviewed in Canada on September 6, 2020

Malcolm K. MillerReviewed in Canada on September 6, 20204.0 out of 5 stars A different Tesla perspective

A good addition to the writings concerning Tesla. His was a talent that could have come from "the stars". I hope the truth is finally realized about his ideas of free electricity

berit pedersenReviewed in the United Kingdom on November 11, 2019

berit pedersenReviewed in the United Kingdom on November 11, 20195.0 out of 5 stars Brilliant and Beautiful.

so good i am giving copies to friends as well. a favourite. anyone who got into the Current War movie may enjoy this too.

fabrizio fontanaReviewed in Italy on February 22, 2017

fabrizio fontanaReviewed in Italy on February 22, 20175.0 out of 5 stars everything else

A real discovery for me. Despite the huge amount of books written on the subject: Nikola Tesla this book enlightens hidden shadows on the inventor. As a consequence it helps to understand a lot about this enigmatic man and his enormous legacy to the modern world. Definitely interesting for whom is in interested to catch the hystory of science at the beginning of 20 century.

-

ゴルビーReviewed in Japan on February 24, 2013

ゴルビーReviewed in Japan on February 24, 20132.0 out of 5 stars がっかり

話が分かりづらすぎます。テスラーの人となりを、もっと盛り込んで欲しかった。

Mr. D. J. UnderwoodReviewed in the United Kingdom on August 11, 2008

Mr. D. J. UnderwoodReviewed in the United Kingdom on August 11, 20084.0 out of 5 stars A review of everything else

The Invention of Everything Else, by Samantha Hunt, provides a kind of biography of the inventer Nikola Tesla, a genius obsessed with electricity, as seen through the eyes of a nosey hotel cleaner, Louisa. The main story is set in 1943, when Louisa comes across the eccentric 86 yr old Tesla who is permenantly resident at the hotel where she works. Largely forgotten by the world and viewed with suspicion by others for suspected anti-American views, Tesla is befriended by Louisa and we slowly learn his life-story through her eyes.

Just like its subject, the book itself is also quirky and written in a somewhat non-linear way. Also, the book devotes just as much space to Louisa interacting with her eccentric father and his friend when you want it to be telling more about Tesla. But I enjoyed the style as it makes a subject that could be for enthusiasts only into something interesting and entertaining. And from a research point of view, a quick check on wikipedia supports much of what relates to Tesla himself. Recommended.