UNLIMITED

Across the divide

On 11 May 2021, I was sitting with a small group in a cafe in southern Tel Aviv, studying Arabic. Our teacher, a Palestinian citizen of Israel, had been telling us that he and his pregnant Jewish wife kept getting turned down by landlords who would not rent their property to a “mixed” couple. We were almost at the end of the three-hour class when air raid sirens sounded. A few days earlier, missiles had been launched from Gaza into Israel, but this was the first time they had hit Tel Aviv. Beyond the fear of an airstrike, I had a sad, heavy feeling. I had recently returned to live in Israel after 15 years studying and working abroad. I remembered a time, in the mid-1990s, when I had believed that Israel was going to be different, more just and less violent. That belief now felt like a distant memory.

My faith in Israel’s future had been inspired by an experience I shared as a teenager with a group of extraordinary people. As we waited for the rocket fire to stop, I recalled one of those people in vivid detail, a person I have barely been able to talk about in my home country for more than 20 years. His name was Aseel Aslih.

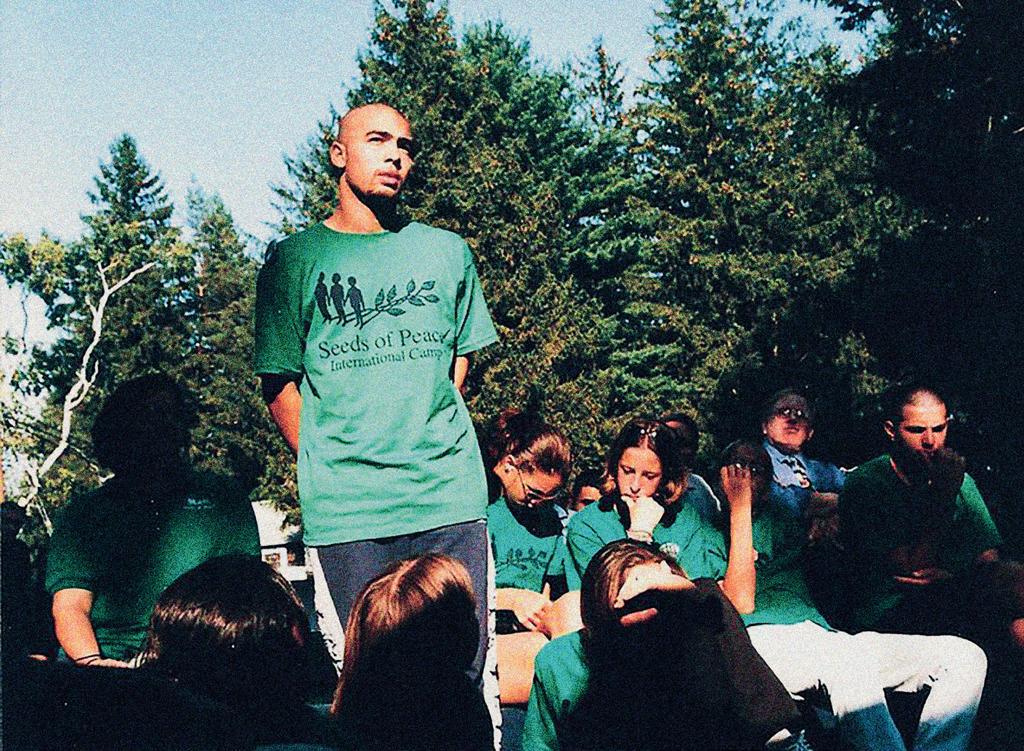

When I first met Aseel, in 1997, he was 14, a Palestinian citizen of Israel from Arrab a in the Galilee and I was 13, a Jew from the Mediterranean city of Ashdod (formerly the Palestinian village Isdud). We had been chosen as Israeli delegates to a summer camp in the US for teenagers from conflict areas. A few months before camp we both attended a preparatory seminar for the Israeli delegation. We didn’t become friends straight away. I was skinny, wore denim overalls and mostly hung out with girls. Aseel was slightly taller than me, physically bigger and already had facial hair. I felt uncomfortable around boys, not sure if they were going to comment on the way I spoke, which at the time I thought was too feminine. But I warmed to Aseel. He had a habit of tilting his head slightly to the side, his cheeks rising as he smiled. In conversation, he lowered his voice and narrowed his eyes, demanding attention.

Our delegation to the summer camp, which was called Seeds of Peace, had been selected by the Israeli ministry of education, which was looking for people with leadership skills and good English. While knowledge of a foreign language is often a product of privilege, neither Aseel nor I came from wealthy families. My father was a taxi driver and my mother worked for the Port Authority; Aseel’s father owned a small business and his mother was an educational counsellor. Our knack for languages and the gift of curiosity made us good

You’re reading a preview, subscribe to read more.

Start your free 30 days