Rupert Sheldrake’s name is probably familiar to readers of Fortean Times. The now 81-year-old academic studied biology and biochemistry at Cambridge and philosophy of science at Harvard and has worked as a researcher for the Royal Society and as a plant physiologist in India. It sounds like an impressive academic resumé; but when you add his work on morphic resonance, the ‘sense of being stared at’ and dogs who know when their owners are coming home (to name just some of his research interests) we see a rather less traditional career pathway. Throw in an attempt on his life and a banned, and much discussed, TED talk (FT302:14-16) and this is clearly someone with an extraordinary set of life experiences. I recently met up with him for a chat.

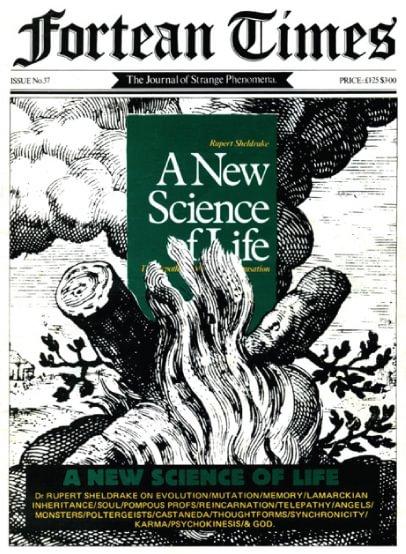

A NEW SCIENCE OF LIFE

I was interested in what had caused a previously traditional scientist to switch paths. Rupert started off as a plant scientist working on auxins (plant hormones) with the traditional route laid out in front of him and enjoying great success in his field. Then, in 1981, he came out with his morphic resonance theory in the book A New Science of Life. What had brought about that change?

“Well the change really took place when I was still in Cambridge. I was a fellow of Clare College, teaching cell biology, and I thought of the idea of morphic resonance in 1973; and the reason I thought of it was that I was doing research on plant development or morphogenesis – the development of form – and I was convinced that the genes alone couldn’t explain it. So I got interested in the idea of morphogenetic fields – form shaping fields – which was first proposed in biology at the beginning of the 1920s. So it was not a new idea – the idea that some kind of invisible form or blueprint or field shapes developing organisms.

In 1982 FT interviewed Rupert Sheldrake about the New Science of Life controversy.

ETIENNE GILFILLAN“The shape can’t be carried in the genes, because all the genes do is programme the synthesis of proteins. So I thought this idea of morphogenetic fields would explain the shape or form of a flower petal because there’s a kind of mould or blueprint for the developing organ. But the big problem was how to understand the inheritance of morphogenetic fields. If they weren’t inherited through genes, then how they be inherited? I couldn’t see any way this could happen, and then I read what was for me a very seminal book, namely by the French philosopher Henri Bergson. This was originally written in 1896 and translated