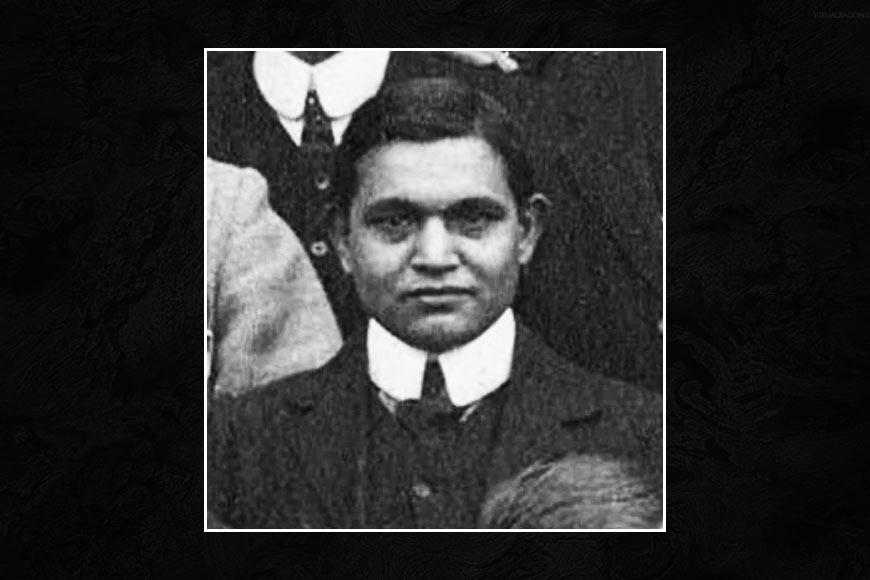

Back when Rev. Lal Behari Dey’s novel won Darwin’s heart

An eminent scholar, from a distant land far across the sea, sent a congratulatory note to a humble author in India via his publisher. The book, written by an unheard-of author, had impacted the reader so intensely that he dashed a letter to the publisher requesting him to convey his regards and deep admiration for the author. It was 19th century Bengal and the author was Reverend Lal Behari Dey, the recipient of the letter. The one to write the letter was the renowned English naturalist, geologist, and biologist Charles Darwin, widely known for contributing to the understanding of evolutionary biology!

Dey was born on 18 December 1824 to a Bengali Suvarna Banik family at Sonapalasi near Burdwan. His father Radhakanta Dey Mondal was a small bill broker in Kolkata. Dey was brilliant in studies and by the age of four, he had completed his primary education in the village ‘pathshala’ and was raring to join high school. His father decided to bring him to Calcutta but all members of his conservative family and relatives were dead against the decision because the consensus at that time was, if a Hindu boy studied in a ‘mlechchha’ (European) school, he will become an agnostic and give up age-old indigenous traditions. Undeterred by all hostilities, Radhakanta brought the young lad to Calcutta to get him admitted to a good school.

Radhakanta was a small bill broker in Calcutta and his meager earnings meant his family had to somehow make ends meet. But due to his prolonged stay in the city, Radhakanta could fathom that Persian, the erstwhile official language of Bengal was being replaced by English. Hence, those who could master the new language would naturally have an edge over other ‘natives’ when seeking employment and would be the first choice for employers at the East India Company. With this scheme in view, he scouted for a school where the emphasis was given to the English language. But lack of funds came his way. He could not admit his son to Oriental Seminary, a renowned school of that time, established by Gourmohan Addhya because he could not arrange Rs. 3/-, the school’s fee. But he did not give up. He wrote letters to his wife, explaining why he was so determined to put Lal Behari in an English school and secure his son’s future.

Also read : Sib Chandra Nundy: The Telegraph Man of India

Finally, Radhakanta zeroed in on Reverend Alexander Duff’s General Assembly Institution (now Scottish Church Collegiate School). This was a free school but Duff made it very clear at the outset that one of the purposes of establishing the school was the promotion and spread of Christianity and warned that if admitted to this school, there was a possibility of his son embracing Christianity in the future and reminded him of the social upheaval in the city a few days ago following Krishnamohan Bandopadhyay’s conversion. After weighing the pros and cons, Radhakanta decided to go ahead and admit Lal Behari to General Assembly Institution. He had no qualms about his resolution. He wanted to ensure his son’s future and provide him with all opportunities to pursue higher education. At that time such a decision was revolutionary indeed.

Dey battled poverty after his father’s death and struggled to get educated. He met David Hare, a philanthropist, and founder of educational institutions like Hindu School, Hare School, and Hindu College (later renamed Presidency College). Lal Behari sought admission to Hare School as it was a stepping stone to Hindu College where several scholarships were offered to meritorious students from financially weaker sections of society. But it was evident that merit alone was not enough to sail him through. Although impressed by Lal Behari’s brilliant academic results, Hare refused his admission because he staunchly believed “Duff’s pupils” would “spoil my boys” by trying to convert them to Christianity.

Despite the rejection, Lal Behari did not harbour any anger or hatred. Later, when he converted to Christianity, it was not an impulsive decision but rather one that was based on his unwavering faith in the religion. Under Duff's tutelage, he formally embraced Christianity on 2 July 1843 at the age of 19. In 1842, a year before his baptism, he published a tract, The Falsity of the Hindu Religion, which had won a prize for the best essay from a local Christian society.

Lal Behari Day was known for his profound knowledge of the English language and literature. He was an educationist and taught English at colleges in Behrampore and Hooghly. He was made a Fellow of the University of Calcutta in 1877. He edited three English journals: Indian Reformer, Friday Review, and Bengal Magazine. During his work at Burdwan, he observed rural life from very close quarters and all his experiences formed the theme of his book, Bengal Peasant Life (1874). During this time, the relations between landlords and peasants were very volatile and there was peasant unrest in different parts of Bengal. Bengal Peasant Life elucidates the reasons that culminated in this situation.

Rev. Lal Behari also wrote two novels, Chandramukhi, A Tale of Bengali Life (1859), and Govinda Samanta, which portray the suffering of peasants under the zamindari system. In 1871, Baboo Joy Kissen Mookerjea of Uttarpara, one of the most enlightened zamindars in Bengal, held a competition for authors to write an essay on "Social and Domestic Life of the Rural Population and Working Classes of Bengal" and announced a cash prize of Rs 500/- for the best entry written either in Bengali or English language. Lal Behari wrote an article on the topic and sent it the following year. But it took two more years to announce the winner’s name because the two experts who were to judge the merits of the entries went to England. Finally, after two years, in mid-1874 Lal Behari’s name was announced as the winner of the competition. Although written in the form of an essay initially, Dey reworked on the manuscript and added three more chapters and 'Govinda Samanta' saw the light of day as a novel.

Dr. George Smith, editor of ‘Friend of India,’ Hon'ble Justice J.B Fier, one of the then-judges of the Calcutta High Court, and E.B. Cowell, an authority in Sanskrit language revised the manuscript of the book. The book was published as ‘Bengal Peasant Life’ and became very popular. It was later translated into multiple languages and was well-received globally. After reading this book, Charles Darwin, author of The Origin of Species, wrote to Lal Behari’s publisher, “I see that Reverend Lal Behari Dey is Editor of the Bengal Magazine and I shall be glad if you would tell him with my compliments how much pleasure and instruction, I derived from reading a few years ago, this novel, Govinda Samanta.”

In 1875, Folk-Tales of Bengal, a seminal work by Dey was published. He was perhaps the first collector of Bengali fairy tales and compiled the book. This scholarly work is a path-breaking effort to catalog the cultural heritage of rural Bengal. This compilation not only preserved folk tales that might otherwise have been lost but also paved the way for the modern study of Folk literature.

Still, the fact remains, we Bengalis suffer from mass amnesia and hence, have failed to pay respect to a pioneer who gleaned and sifted various sources to pick up the choicest gems of our indigenous folk literature and handed us this rich treasure trove. It has been close to 200 years (his bicentenary will be held in two years) but we are yet to acknowledge our gratitude.