What do you think?

Rate this book

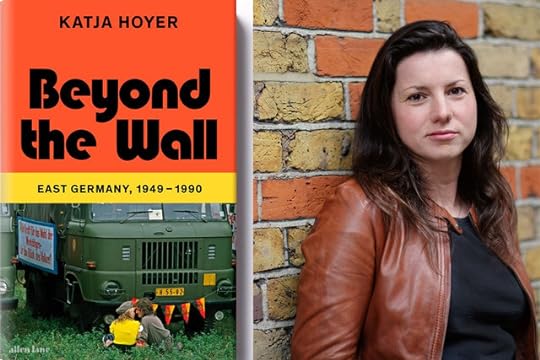

496 pages, Hardcover

First published April 6, 2023

"...The ups and downs of the GDR as a political, social and economic experiment have left a mark on its former citizens, who have brought these experiences with them – and not as mere ‘ballast’. Millions of Germans alive today neither can nor want to deny that they once lived in the GDR. While the world that had shaped them fell with the Berlin Wall in 1989, their lives, experiences and memories were not razed with it. Yet the way much of the Western world saw it, the GDR had well and truly lost the Cold War on German soil, morally invalidating everything in it. When the German Democratic Republic vanished literally overnight on 3 October 1990, it lost the right to write its own history. Instead it had become history. And history is written by victors – East Germany’s is no exception."

"This book traces the roots of the German Democratic Republic beyond its foundation to provide context for the circumstances out of which the country was born in 1949. I outline the developments that followed through all four decades rather than treating them as a static whole. In the 1950s, the infant republic was almost entirely preoccupied with stabilizing its foundations politically and economically. It did so both with and over the heads of its citizens, resulting in a decade that was marked by a can-do spirit as well as violent outbreaks of discontent."

"...In a bitter twist of fate, those who had been incarcerated by the Nazis in early concentration camps in 1933 made it to the top of the list of suspicious individuals. In the eyes of Stalin and his henchmen, anyone who had escaped Hitler’s clutches must have given the Nazis something in return. Perhaps a promise to infiltrate the Soviet Union, get a job in a munitions factory and begin to organize systematic sabotage to prepare a German invasion."

"Now, it is time to dare to take a new look at the GDR. Those who do so with open eyes will find a world full of colour, not one of black and white. There was oppression and brutality, yes, and there was opportunity and belonging. Most East German communities experienced all of this. There were tears and anger, and there was laughter and pride. The citizens of the GDR lived, loved, worked and grew old. They went on holidays, made jokes about their politicians and raised their children. Their story deserves a place in the German narrative. It’s time to take a serious look at the other Germany, beyond the Wall..."