What do you think?

Rate this book

261 pages, Paperback

First published March 1, 2007

come to my blog!

come to my blog!(Sobre su hija) “Emily tiene algo de gato, y siempre he pensado que los gatos solo saltan a tu regazo para comprobar si estás lo bastante fría para comerte.”Hay pequeñas joyitas:

“Hablaba un irlandés precioso. La lengua era para él un lugar romántico, y es el lugar donde aún sigo queriéndolo.”Y hay otras tantas con las que, después de pelearte un buen rato, te preguntas si no te tendrías que tomar ese whisky o esa cerveza de malta o ponerte bajo la lluvia a ver si te despejas un poco y pillas todo el sentido de la frase:

“Podía coger las llaves y volver a «casa», donde podría «hacer el amor» con mi «marido», igual que tantas otras personas. Eso era lo que había hecho durante años. Y hasta que mi hermano murió no parecieron importarme las comillas ni me di cuenta de que estaba viviendo entre ellas.”

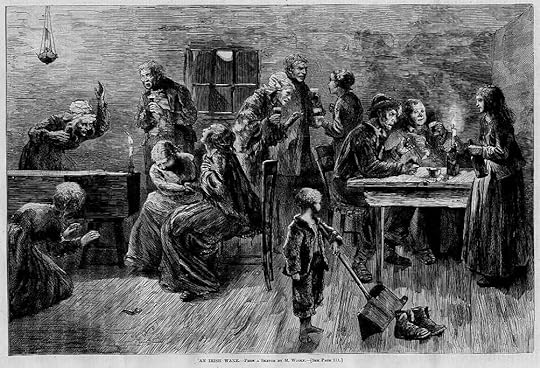

“No hay nada tan incierto como la caricia de una anciana, tan cariñoso o tan horrible”La historia en sí está llena de tópicos irlandeses, como el alcoholismo, las familias numerosísimas, la culpa católica, el abuso a menores. Todo se perdona en virtud de la maravillosa forma en la que está contada. Todo el libro es un largo monólogo de Verónica que nos cuenta la historia de su familia, los Hegarty, a raíz de la muerte de uno de sus once hermanos. Como buen monólogo, la historia no es lineal, recuerdos traen otros recuerdos, ideas que se van enlazando, pequeñas historias de sus abuelos, de sus padres, de sus hermanos, se entremezclan con su vida, con el momento en el que celebran el funeral y el entierro de su hermano y los meses posteriores. La culpa es la gran protagonista... y quizás el destino, porque aunque a veces parece que un hecho terrible del pasado concentra todo el peso de la caída y posterior muerte de su hermano (y toda la responsabilidad en ella y el resto de la familia), también pone en el otro platillo de la balanza aquello contra lo que es muy difícil luchar:

“Lamb Nugent nunca la dejó. Mi abuela fue su acto más imaginativo. Puede que yo no se lo perdone, pero es eso –la forma en que fue fiel a ese acto creativo– lo que mejor define al hombre, para mí.”

“No es que los Hegarty no sepamos lo que queremos, sino que no sabemos cómo quererlo. En nuestro deseo hay algo que se descarrió sin remedio.”

I do not know the truth, or I do not know how to tell the truth. All I have are stories, night thoughts, the sudden convictions that uncertainty spawns. All I have are ravings, more like.

They are a bundle of nerves, frayed at the ends. They are wearing each other away; both of them amazed by the thinness of skin that happens just there; how close they can be, blood to blood, so that the ticking, afterwards, of one inside the other, might be a joke, or a pulse-the beating in your veins of someone else's heart.

People, she used to think, do not change, they are merely revealed.

I would like to write down what happened in my grandmother’s house the summer I was eight or nine, but I am not sure if it really did happen. I need to bear witness to an uncertain event. I feel it roaring inside me – this thing that may not have taken place. I don’t even know what name to put on it. I think you might call it a crime of the flesh, but the flesh is long fallen away and I am not sure what hurt may linger in the bones.From this ominous beginning, Veronica meanders back to the time of her grandmother, constructing a narrative that is part family history, part “Dear Diary”—a public confessional in which you can imagine Veronica tearing at the pages with the sharp tip of her pen. Enright presents us with an articulate, reflective narrator, but one of the book’s most brilliant aspects is the instability of Veronica’s testimony – highlighting the unreliability of memory.

My mother had twelve children and— as she told me one hard day–seven miscarriages. The holes in her head are not her fault. Even so, I have never forgiven her any of it. I just can’t.This tells us so much about the soul of the woman who leads us into her family’s past, the volumes of sorrow and anger and shame that swell in her heart like pages of a book left out in the rain. Perhaps it is her mother’s carelessness, or reverence to a religion which treated women like brood sows that Veronica cannot forgive; but no, as she tells us, “I do not forgive her the sex. The stupidity of so much humping. Open and blind. Consequences, Mammy. Consequences.”

There is always a drunk. There is always someone who has been interfered with, as a child. There is always a colossal success, with several houses in various countries to which no one is ever invited. There is a mysterious sister. These are just trends, of course, and, like trends, they shift. Because our families contain everything and, late at night, everything makes sense. We pity our mothers, what they had to put up with in bed or in the kitchen, and we hate them or we worship them, but we always cry for them.