What do you think?

Rate this book

909 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1349

a) degetul Sfîntului Duh, nevătămat și întreg,

b) o unghie de heruvim,

c) un petic din veșmîntul sfintei Credințe catolice,

d) cîteva raze din steaua urmată cîndva cu încredere de magii de la Răsărit,

e) falca morții sfîntului Lazăr,

f) un sfînt canin din sfînta dantură a Sfintei Cruci,

g) o fărîmă din sunetul clopotelor adăpostite în templul lui Solomon,

h) o pană din aripile arhanghelului Gabriel, căzută în timpul Bunei Vestiri...

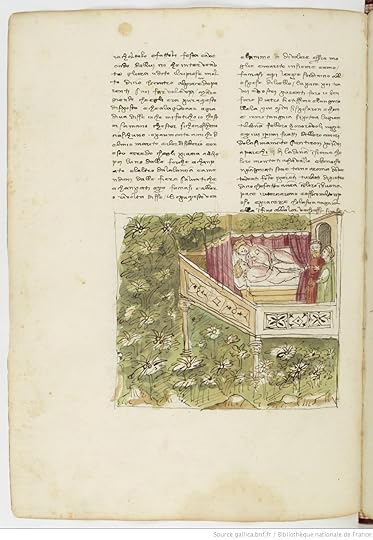

Then after many kisses they went to bed together and took delight and pleasure one of another almost all that night, hearing the nightingale sing many a time.

There he held a lavish and honourable wedding-feast and afterwards went after nightingales with her, in peace and solace and at length, both by night and by day, to his heart's content.

'What you have there is the pit of Hell,' said Rustico, 'and I have to say that I believe God sent you here for the salvation of my soul.

For even if this devil torments me so mercilessly, if you will take pity on me and let me stuff him back into Hell, you'll give me great consolation and you'll really please God and serve Him, if that's what you've come to these parts to do, like you told me.'

The girl answered him in all good faith: 'Oh, my father, seeing that I have this pit of Hell, let it be done whenever you like.'

'Bless you, my daughter!' said Rustico then. 'Let us go then and stuff him back in there right away, so he'll leave me in peace afterwards.'

And with these words, he led the young girl over to one of their little beds, and showed her how one sets about imprisoning that cursed enemy of the Lord.

The young girl, who had never had any devil in her pit of Hell before that moment, felt some pain the first time, and so she said to Rustico, 'There's no doubt, father, that this devil must be a wicked thing altogether, and a real enemy of God, for even the pit of Hell, let alone anything else, is sore when he's stuffed back in there.'

"'Alack!' rejoined the other, 'what is this thou sayest? Knowest thou not that we have promised our virginity to God?'

'Oh, as for that,' answered the first, 'how many things are promised Him all day long, whereof not one is fulfilled unto Him! An we have promised it Him, let Him find Himself another or others to perform it to Him.'"

"Whereupon Rustico, seeing her so fair, felt an accession of desire, and therewith came an insurgence of the flesh, which Alibech marking with surprise, said: 'Rustico, what is this, which I see thee have, that so protrudes, and which I have not?'

'Oh! my daughter,' said Rustico, ''tis the Devil of whom I have told thee: and, seest thou? he is now tormenting me most grievously, insomuch that I am scarce able to hold out.'"

"...nor did she ever water these with other water than that of her tears or rose or orange-flower water."-----------------

"As often, most gracious ladies, as, taking thought in myself, I mind me how very pitiful you are all by nature, so often do I recognize that this present work will, to your thinking, have a grievous and a weariful beginning, inasmuch as the dolorous remembrance of the late pestiferous mortality, which it beareth on its forefront, is universally irksome to all who saw or otherwise knew it."

"There are then, discreet ladies, some who, reading these stories, have said that you please me overmuch and that it is not a seemly thing that I should take so much delight in pleasuring and solacing you; and some have said yet worse of commending you as I do."

… nothing is so indecent that it cannot be said to another person if the proper words are used to convey it…

“But as I'm sure you know, laws should be impartial and should only be enacted with the consent of those affected by them. In the present case, these conditions have not been met, because this law applies only to us poor women who are much better than men at giving satisfaction to a whole host of lovers. Moreover, when it was passed, not only were there no women present to give their consent to it, but since then, not once have they ever been consulted about it. And that's why, for all these reasons, it could with justice be called a bad law.” [6.7]

“My lady, this guy wants to teach me all about Sicofante’s wife, and just as if I weren’t acquainted with her at all, he would have me believe that the first night Sicofante went to bed with her, Messer Mace entered Black Mountain by force and with much bloodshed. But let me tell you, that’s not true; he entered it peacefully and to the general contentment of those inside.”

‘Madam, this fellow thinks he knows Sicofante’s wife better than I do. I’ve known her for years, and yet he has the audacity to try and convince me that on the first night Sicofante slept with her, John Thomas had to force entry into Castle Dusk, shedding blood in the process; but I say it is not true, on the contrary he made his way in with the greatest of ease, to the general pleasure of the garrison.’