What do you think?

Rate this book

181 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1975

Mr. Fukuoka harvests between 18 and 22 bushels (1,100 to 1,300 pounds) of rice per quarter acre. This yield is approximately the same as is produced by either the chemical or the traditional method in his area.

Trees weaken and are attacked by insects to the extent that they deviate from the natural form.

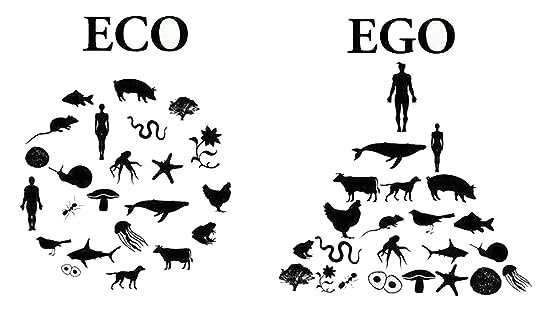

And the scientists, no matter how much they investigate nature, no matter how far they research, they only come to realize in the end how perfect and mysterious nature really is. To believe that by research and invention humanity can create something better than nature is an illusion.

You hear a lot of talk these days about the benefits of the "Good Rice Movement" and the "Green Revolution." Because these methods depend on weak, "improved" seed varieties, it becomes necessary for the farmer to apply chemicals and insecticides eight or ten times during the growing season.

Foods that have departed far from their wild state and those raised chemically or in a completely contrived environment unbalance the body chemistry.

It is said that Einstein was given the Nobel Prize in physics in deference to the incomprehensibility of his theory of relativity. If his theory had explained clearly the phenomenon of relativity in the world and thus released humanity from the confines of time and space, bringing about a more pleasant and peaceful world, it would have been commendable. His explanation is bewildering, however, and it caused people to think that the world is complex beyond all possible understanding. A citation for "disturbing the peace of the human spirit" should have been awarded instead.

It is nothing you can really talk about, but it might be put something like this: "Humanity knows nothing at all. There is no intrinsic value in anything, and every action is a futile, meaningless effort." This may seem preposterous, but if you put it into words, that is the only way to describe it.

"_The One-Straw Revolution_ is one of the founding documents of the alternative food movement, and indispensable to anyone hoping to understand the future of food and agriculture."—Michael Pollan

"Only the ignorant could write off Fukuoka, who died two years ago at the age of 95, as a deluded or nostalgic dreamer...Fukuoka developed ideas that went against the conventional grain....Long before the American Michael Pollan, he was making the connections between intensive agriculture, unhealthy eating habits and a whole destructive economy based on oil." --Harry Eyres, The Financial Times

"Fukuoka's do-nothing approach to farming is not only revolutionary in terms of growing food, but it is also applicable to other aspects of living, (creativity, child-rearing, activism, career, etc.) His holistic message is needed now more than ever as we search for new ways of approaching the environment, our community and life. It is time for us all to join his 'non-movement.'"—Keri Smith author of How to be an Explorer of the World

“Japan’s most celebrated alternative farmer...Fukuoka’s vision offers a beacon, a goal, an ideal to strive for.” —Tom Philpott, Grist

“_The One-Straw Revolution_ shows the critical role of locally based agroecological knowledge in developing sustainable farming systems.” —_Sustainable Architecture_

“With no ploughing, weeding, fertilizers, external compost, pruning or chemicals, his minimalist approach reduces labour time to a fifth of more conventional practices. Yet his success in yields is comparable to more resource-intensive methods…The method is now being widely adopted to vegetate arid areas. His books, such as The One-Straw Revolution, have been inspirational to cultivators the world over.” —_New Internationalist_

Product DescriptionCall it “Zen and the Art of Farming” or a “Little Green Book,” Masanobu Fukuoka’s manifesto about farming, eating, and the limits of human knowledge presents a radical challenge to the global systems we rely on for our food. At the same time, it is a spiritual memoir of a man whose innovative system of cultivating the earth reflects a deep faith in the wholeness and balance of the natural world. As Wendell Berry writes in his preface, the book “is valuable to us because it is at once practical and philosophical. It is an inspiring, necessary book about agriculture because it is not just about agriculture.”

Trained as a scientist, Fukuoka rejected both modern agribusiness and centuries of agricultural practice, deciding instead that the best forms of cultivation mirror nature’s own laws. Over the next three decades he perfected his so-called “do-nothing” technique: commonsense, sustainable practices that all but eliminate the use of pesticides, fertilizer, tillage, and perhaps most significantly, wasteful effort.

Whether you’re a guerrilla gardener or a kitchen gardener, dedicated to slow food or simply looking to live a healthier life, you will find something here—you may even be moved to start a revolution of your own.

Tôi đã dành ba mươi năm, bốn mươi năm để kiểm nghiệm xem liệu mình có nhầm lẫn hay không, vừa làm vừa nghiền ngẫm, nhưng chưa lần nào tôi tìm ra được bằng chứng chống lại điều ấy cả.

knowledgeable readers will be aware that Mr. Fukuoka's techniques will not be directly applicable to most American farms.and I'm sure this applies even more to where I live. But the problems discussed here and others - nitrogen runoff, soil depletion, the insect apocalypse - aren't going away. At some point we, or our children, will have to build a more sustainable relationship with the soil.