Unprecedented. A radio announcer used that word Monday while talking about the region’s reaction to coronavirus. Yet a look back at 1918, to the so-called Spanish influenza pandemic, is a glimpse at fears and prevention steps not so different from what we see today.

“Health Board Stops All Public Gatherings,” said The Everett Daily Herald’s banner headline on Oct. 8, 1918.

The Everett Board of Health ordered the closure of all public schools. The ban included church services and gatherings at theaters, pool halls and fraternal organizations. The library and YMCA also had to close, said Dr. John Beatty, Everett’s health officer 102 years ago.

Worldwide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the 1918 pandemic killed about 50 million people — at least 675,000 in the United States.

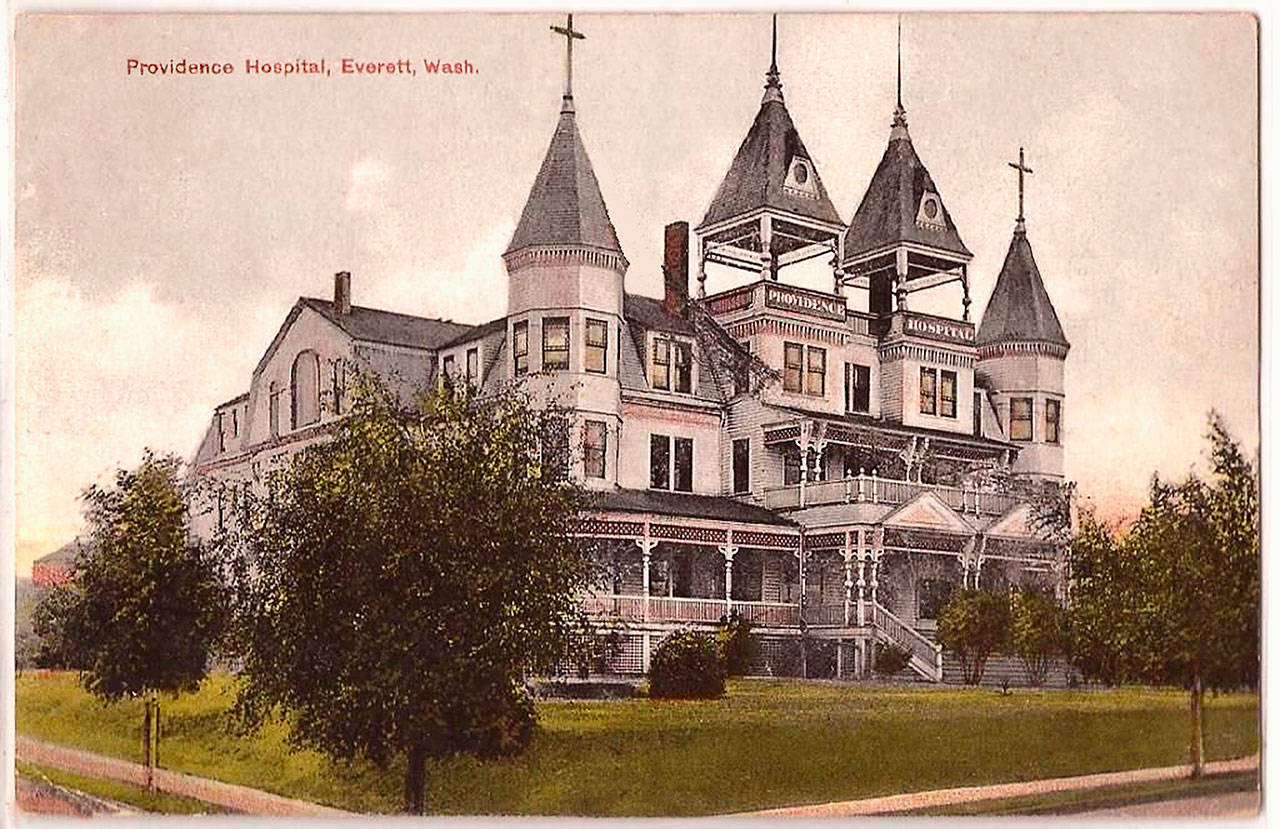

By mid-October 1918, the board was getting reports of 50 new flu cases each day in Everett, according to “Heritage: The History of Providence Hospital, Everett 1905-1980.” Like neighboring cities, “Everett was hit full force, leaving all 17 Providence nurses feverish in bed,” the publication said.

On Nov. 4, 1918, the state Board of Health announced a requirement that everyone wear a gauze mask in public.

Two nurses and 32 others had died of flu at Providence, then in the original Monte Cristo Hotel building, by Nov. 12, 1918. That was just a day after the armistice that ended World War I was signed. Flu, in fact, killed more people than the Great War.

Today, outside Providence Regional Medical Center Everett’s Colby Campus, a big blue tent awaits people who may show up with suspected symptoms of COVID-19. It’s a tangible sign of these nervous times, right near the hospital’s 14th Street entrance — two blocks from my house.

“We are setting up the tent in case we see an influx of patients, as it provides a place to screen people for symptoms before they enter the hospital to ensure appropriate care,” said Casey Calamusa, Providence Health & Services communication director.

He said Monday that people should come to the emergency department only “if it is a true emergency.” People with mild symptoms should call their primary care provider or use the Providence ExpressCare Virtual online service, Calamusa said.

The New York Times this week noted differences between today’s outbreak and the 1918 flu. Caused by an H1N1 virus with genes of avian origin, its “Spanish” label was a misnomer. Wartime censorship rules allowed reporting on the disease in neutral Spain, but not in other parts of Europe.

“The fear is similar, but the medical reality is not,” said Monday’s New York Times article by Gina Kolata.

Medically, the world is vastly different now. In 1918, the genetic material of viruses hadn’t yet been discovered. Testing wasn’t possible. Health workers had neither sufficient protective gear nor respirators to care for the very sick, said The New York Times article.

The Everett Public Library’s Northwest Room staff compiled a local history of the Spanish influenza from Herald coverage and other sources. Also called “La Grippe,” the flu appeared in Sierra Leone and France before striking U.S. Army soldiers at Fort Riley, Kansas, where it killed 46. It spread across the country largely by troops going to or returning from war.

In Seattle, 1,772 Spanish flu deaths were reported, according to the book “Washington: The First 100 Years 1889-1989.” According to the HistoryLink website citing U.S. Census Bureau Mortality Statistics, 4,879 people in Washington state died of flu in 1918. More than half were young adults, between ages 20 and 39.

With nurses and five Sisters of Providence stricken, volunteers helped at the Everett hospital. On Oct. 25, 1918, the Herald reported the death of Miss Mayme T. Downs, a volunteer who’d cared for Cecilia Hart, a nurse who died.

An emergency hospital, run by the Red Cross, opened in Everett in mid-October 1918 and closed a month later. The Snohomish County Superior Court shut down, and public phones were declared a menace.

The 1918 flu cut across social and economic classes. It killed N.C. Rhoads, superintendent of Sultan schools; 23-year-old Percy Marsh, a worker at Everett’s Weyerhaeuser Mill B; and 15-year-old Leah Miller. Everett natives serving in the military died, among them J. Fred Green and David Elster at the Army’s Fort Worden in Port Townsend.

Flu also forced cancellation of the 1919 Stanley Cup championship game, a hockey bout that would have been pitted Seattle’s Metropolitans against the Montreal Canadiens. Montreal player Joe Hall died of it.

On Nov. 12, 1918, after more than a month, Everett lifted its “flu ban.” Routines of life returned, the Herald reported. Schools, churches and theaters reopened — some redecorated.

“Just like that out of the news,” said the Everett library’s summary of the 1918 pandemic. “It kind of disappeared with the War after the Armistice.”

Julie Muhlstein: 425-339-3460; [email protected].

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.