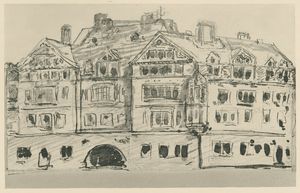

Positioned directly across the avenue from the imposing Waldo Mansion that houses Ralph Lauren's flagship store today once stood a more exhilarating building, among the most notable that ever existed in the city.

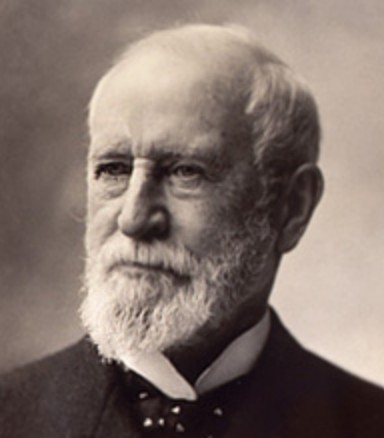

Previous economic downturns affecting alike the meager lives of workers and the grandiloquent imaginings of plutocrats offer ample proof of how little has fundamentally changed over past generations. In 1882, Charles Lewis Tiffany, a founder and principal owner of New York's preeminent jewelry dealers, Tiffany & Company had engaged the new partnership of McKim, Mead & White to design his unique residence on the northwest corner of Madison Avenue and 72nd Street.

From the start it was his brilliantly artistic youngest son, Louis Comfort Tiffany, who assumed control of the project. Working intensively with his friend and sometime associate, architect Stanford White, Tiffany drew up a schematic elevation that was adapted to make the 57-room mansion one of New York's most beautiful and unusual works of architecture.

It was completed 1885, a year after the death of Louis Tiffany's first wife, Mary Woodbridge Goddard. This tragedy left the sensitive Tiffany a distraught widower with four small children. Plunging into ever more work, he attempted to dispel overwhelming grief. Inasmuch as both palatial structures were, in effect, glorified multiple dwellings, in terms of organization the Tiffany house echoed the McKim, Mead & White firm's contemporary effort for journalist and railroad magnate Henry Villard, on Madison Avenue, between 52nd and 53rd Streets.

Stylistically, these remarkable groups diverged completely. An evocation of a Renaissance Roman Palace, the U-shaped Villard houses were heavily indebted to the restrained aesthetic sensibilities of the partnership's young associate, Joseph Wells. The Tiffany's baronial brick and sandstone pile, combining aspects of Romanesque and Queen Anne architecture, on the other hand, was something else. It was the culmination of all that Stanford White had mastered as an apprentice to the great Henry Hobson Richardson, who had taught his gifted pupil about how to best manipulate precedent and form, to bring to a logical plan, the most picturesque composition obtainable.

Generally referred to as Louis Tiffany's house, 27 East 72nd Street was, in fact, four separate houses. Quite unlike the complex of unified individual residences created for Villard, as with apartments, except for 898 Madison Avenue in this ensemble, here the separate houses were stacked around a courtyard, one atop the other. Number 898 Madison Avenue was initially home to Charles Tiffany's married daughter, Mrs. Alfred Mitchell. Of the apartments, the first, on the ground, first and second floors, had been intended for Charles Tiffany and his wife, Harriet Olivia Avery Young. Obstinately, modestly, they were never to occupy it and remained in Murray Hill at 255 Madison Avenue. Taking up the third storey, a second apartment was meant to be occupied by their unmarried daughter, Louise Tiffany, who, instead, remained downtown with her parents. Below a massive gabled roof, covered in pan-tiles and lighted by quaint windows, dormers and skylights, the fourth and fifth floors were reserved for Louis Comfort Tiffany and his family.

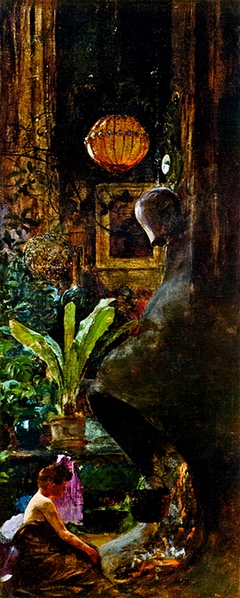

Highly complex, the interior volume that contrasts low and high, connected, loft-like spaces in Tiffany's apartment, were surfaced with humble, mostly unembellished concrete. The exposed I-beams of steel framing were another radical departure from common practice.

Much as in any modern setting, the uniform masonry backdrop was an effective foil for displaying concentrated decorative assemblages. Ornate stained glass, cleverly wrought Japanese sword guards, antique lacquerware, collections of porcelain, intricate Indian carvings , woodblock prints and other extraordinary ornaments, were all ingeniously disposed like elements in a marvelous, color-filled mosaic. It was by this means, artfully juxtaposing old and new, rich and plain, by which the occupant made his home a revealing and arresting work of art.

The studio, on the uppermost level of Louis Tiffany's duplex, was actually the equivalent of three or four conventional stories in total height. It featured a mammoth, open space directly under the roof. At its center was a sculptural, four-hearth fireplace. This focal point rose from the floor in an Art Nouveau flourish, culminating in a tree trunk-like concrete chimney.

Suspended from the sloping ceiling was a veritable constellation of decorative ironwork, brasses and iridescent glass pendant lamps.

Every sensuous constituent conceivable was enlisted to contribute to an eclectically exotic atmosphere of mystery and delight. Perfumed by a profusion of frequently changed blooming hothouse plants, enlivened by leaping firelight, from driftwood, chemically treated to produce different colored flames, Tiffany's environment was also amplified by haunting music from a large pipe organ.

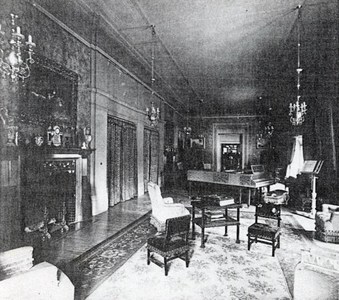

Assisting Louis Tiffany in decorating the entire house was the incomparable team of Stanford White, Lockwood de Forest, who manufactured carvings in India, textile specialist Candice Wheeler, glass worker John La Farge and the sculptor, Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Members of the Associated Artists, a firm of interior designers, they had recently collaborated on the inventive Seventh Regiment Amory's Veteran's Room. Decorations they devised for spaces originally planned for Tiffany's parents, on the lower stories, were no less creative than their work upstairs.

In the mosaic-floored stair hall, sheathed in panels of delicately veined white marble, they wrapped a broad flight used by family and guests, around the unseen, partly-enclosed staircase for servants. Including dramatically changing floor levels, varied perspectives and vistas, making one's way via either route, a succession of surprises lay in store. Emerging from, or entering into an enclosure of translucent glass, or a screen of slender columns, leaving or approaching, comparative dark at the bottom and cascades of glistening light from the top, made taking the stairs, unexpectedly, into an aesthetic adventure, as opposed to a merely mundane necessity.

Crowned by an enveloping stenciled barrel vault, that must have made visitors feel as though they were inside of a fantastic, vast lidded casket, or trunk, the 'Charles Tiffany' dining room focused on the fireplace wall. Divided into three distinct sections, highlighting the hearth, an over-mantle frieze and a surmounting clock, it was embellished by glass mosaics, bas reliefs, and stenciled rosettes. Ordinary, to the point of approaching the pedestrian, the room's brass gas chandeliers were transformed into atmospheric luminars by mismatched red glass globes. Across the hall, the lengthy music room similarly employed unexceptional elements in a novel way, to create a distinguished décor reminiscent of the finest output of Norman Shaw and William Morris in London.

Bankrupted for a second time by the mid 1880's, it was to these wonderful spaces, intended for the Charles Tiffanys, to which Henry Villard moved with his family at a favorable rent, (Happily, at the time of his death in 1900, Villard was quite wealthy once more.) By 1895, the entire complex, with the exception of 898 Madison had been acquired by J. P. Morgan's personal lawyer, Lewis Cass Ledyard. The acclaimed attorney and his family occupied the portion of the house intended for Charles Tiffany that had been leased by Villard. Louise Tiffany's intended third storey base was leased to friends, who in 1912 included Miss Caroline de Forest, (cousin of Louis Tiffany's partner, Lockwood de Forest), Mrs. N. Newlin Hooper, Mrs. Frances Isabel Morris, and Miss Mary R. Callender. By 1909, supervised by architects Janes & Leo, Louis Tiffany divided 898 Madison Avenue into five units which were afterward occupied by family and friends, as well.

On November 9, 1886, Louis Comfort Tiffany married Louise Wakeman Knox. Ultimately having one son and three daughters, in 1905 the couple built a new country house for their 'blended family' at Oyster Bay. Formerly they had summered there, inhabiting an old farm house. Luxurious and unusual, Laurelton Hall, even better than Tiffany's house in town, represented a highly personal self-portrait of its builder, where he would utilize every aspect of his considerable genius.

Presciently anticipating the abstraction and simplification of modernism, by the close of his productive career, Tiffany's decorating operation, the Tiffany Studios, was reduced to planning largely derivative designs and schemes, exactingly based on historic period examples which were increasingly fashionable after 1900. How unfortunate that he was unable to embrace the new movement. How criminal that, despite careful planning, the Great Depression of the 1930's, contributed to the destruction of both of his still-memorable houses.

Louis Tiffany died in the 72nd Street house in 1933. His family's great mansion was demolished in 1936. It was replaced by a large apartment building, 19 East 72nd Street. Designed by Mott B. Schmidt with Rosario Candela, it's adorned by sculptural reliefs around the principal doorway by C. P. Jennewien. Where the gabled and turreted Tiffany House, with its multiple balconies and portcullised arched entry, was as eye-catching, in its way, as the Guggenheim, this tasteful structure, as handsome as it is, more modestly aspires to little beyond anonymity. In the wake of financial hard times such reticence was deemed to be far more 'polite' and even more 'distinguished', than Louis Comfort Tiffany's artistic bravura.