Change Your Image

tork0030

Reviews

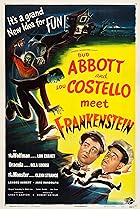

Bud Abbott and Lou Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948)

The crashing of symbols

Comedians are uncomfortable about symbolism in their schtick. A routine that wowed 'em in vaudeville, radio, movies, and TV is just a schtick -- a bit, a gag, a routine that lets the clown collect laughs and a paycheck. But if we are to remember, relish, and celebrate our baggy pants ancestors of the Twentieth century we shall have to look for, and enjoy, the symbolism that indirectly and unintentionally grows in their films down the tunnel of Twenty First century vision. In A & C Meet F we find the brash duo of Bud and Lou confronting the very real ghouls of cinema horror. Vampire. Science demonized. And brute animal rage. Nobody who had a hand in this luscious harem scarem has ever claimed the movie was anything but a quickie comedy to take advantage of the top comedians of the era and the quirky monsters Universal studios had under contract. Yet the subtext is there and gives the film an amazing philosophic undertow. Dracula represents the relentless bloodsucking of a capitalism gone mad; a financial religion that drained mankind with The First World War, The Great Depression, and numerous other fiscal follies. The Frankenstein Monster is nightmare science -- radiation and pollution and genetic mutations run amuck. The wolfman is the bestial element in all mankind, barely restrained at the best of times and when let loose undiscriminating in carnage and outrage. We are all afraid of these things. And so are Bud and Lou. But the message, the philosophy, of the movie shows us two uneducated upstarts armed only with good hearts and good intentions soundly defeating the supernatural and corrupt powers that have plagued mankind since Adam shook hands with Eve and asked what was for dinner. This movie is utterly manipulative; you're supposed to laugh here and shiver there, once you've paid the price of admission. Nothing more. Yet a moments pondering leaves us with the happy thought that perhaps, just perhaps, somewhere there are a couple of dimbulbs, weak as the rest of us, who have enough sanity and grace to disembowel the fears that stalk us. They are neither angels nor devils, and never will get straight just exactly who is on first, but for a few glorious reels they show us a goofy courage and honesty that can keep us looking up, even when we are spiraling down.

Sleeper (1973)

To sleep perchance to laugh

The belly laugh is both illegitimate and orphaned in today's cinema comedy. Writers, directors and performers will go for the gross-out laugh or the cerebral titter, but nudge them towards the broad plains of slapstick and they come down with Pecksniff Fever, the symptoms of which are a sickly desire to edit out real-time physical humor, inability to perform the double-take and constant complaining that the opportunities in front of them are "kids stuff". The best cure for these whining victims is a constant dose of Woody Allen's movie SLEEPER. Allen pulls faces, takes pratfalls and battles a giant pudding with the panache of an old-fashioned troupe of circus clowns. The Dixieland jazz score, with its screaming clarinets and yodeling trombones, is reminiscent of the old Marvin Hatley scores that so aided and abetted the shenanigans of The Little Rascals and Laurel & Hardy in the mighty days of slapstick yore. SLEEPER is one long chase, with Allen evading the authorities in various disguises or simply girding up his loins and skipping away like a madman. Even when caught and brainwashed he still manages to botch up the computer tapes he is assigned to handle, turning them into something resembling the remains of a taffy pull. The music, the pacing, the frantic acting; it all conspires to stir up our diaphragm to the bursting point. We have to guffaw and let the tears stream down our raw cheeks as Allen unerringly out-Chaplins Chaplin and out-Three Stooges the Stooges. This kind of movie teaches us how to laugh out loud. Allen has gone on to bigger(?) and better(?) things since this movie but he's never since been able to tickle himself into such an exuberant physical frenzy. Most great clowns are pretty sad mental cases, so perhaps we need to place the blame for the current drouth of belly laughs with Prozac and the other physcotropic drugs that now rid our creative zanies of their demons.

Top Hat (1935)

The real star of the movie

When whipping up the froth of a musical comedy most creators and commentators forget that fateful second word . . . COMEDY. Not to take away from Astaire & Rogers' beautiful balletic grace, but no one ever gave more comedy more modestly yet more professionally than Edward Everett Horton. His triple-barreled name alone suggests haughty dignity and sniffing puritanism, and his role in this film, as in so many others, gives him ample scope to screw up his mouth in petty disdain, look aghast at social blunders, and sputter in disbelief over the foibles of others while generously ignoring his own idiocies. Horton is a reactor, one which boosts a fairly pedestrian plot to the Moon & beyond. Like Margret DuMont with the Marx Brothers, there is something about the pernickity Horton that begs us to tilt his top hat and fling a banana peel his way just for the delightful reaction we are sure of getting. Perplexed or chagrined, the hatchet-faced Horton is a monument to the lost art of supporting clown -- those dumb bunnies and prissy busybodies that used to inhabit movies and give them life & breath even when the big-shot stars were off the screen. Horton had impeccable timing in delivering a line or flashing a double-take -- you feel he could just as easily count the nano-seconds between the neutron pulses of an atom. If he seems to intrude too much into the musical numbers of this movie it's simply because the director/editor must have been overly fond of his coy mugging. I recommend that music lovers rewatch this film and concentrate on Edward Everett Horton. Your attention will be well-rewarded with deep chuckles and an abiding affection for this New England zany.

Dames (1934)

Hugh is huge

An old theatrical term for what an accomplished character actor/actress could do onstage is "chew on the scenery". This vigorous description perfectly fits the shenanigans of Hugh Herbert in the movie DAMES, among others. Herbert spent a lifetime portraying bumptious simpletons and no one did it better, chewing the cinema scenery to ribbons. His face alone is a comedy mask; with the baggy eyes of a dullard, the potato nose of a busybody, and an agile mouth that could pout like a child or grin like a gargoyle. Reviewing this movie I am astounded at how fun it is to watch a professional idiot at work. Long, long before there was DUMB & DUMBER there was Hugh Herbert -- the dumbbell's dumbbell. Herbert's mature looniness (he never looked young in the movies) is what Jerry Lewis should have evolved to. The dignified business suit, the twinkle of dementia in his eyes, the body-wrenching double-takes, and the arms that flap and flutter and skitter like a thing alive & apart from the brain -- in cold print they seem like slapstick cliches -- as indeed they are -- but in the hands of a master clown like Herbert these mannerisms convey a startling & enthralling portrait of the dimbulb par excellance. Herbert is a comedy hallucination and as such fits perfectly with the weird musical numbers in this film staged by Busby Berkley. When all is said & done, the dancing just a trail of dust & the music just an echo, there still remains the ineffable sight of Hugh Herbert playing with his toy elephants or battling a profound case of hiccups. Herbert gives silliness a stature it has never since attained again.

The Sin of Harold Diddlebock (1947)

The last laugh

The last laugh of any great clown is interesting, if only for its memento mori value. Laurel & Hardy's last film, UTOPIA, is sadly botched but moments of their grand comedy still flair up, like Marc Antony's final bravery in Shakespeare's Antony & Cleopatra. The grandiose W.C. Fields still holds his own in SONG OF THE OPEN ROAD, even though he was deathly ill with alcohol poisoning. The Marx Brother's LOVE HAPPY is mainly a vehicle for one last pantomime fling for brother Harpo -- and all the more poignant for it. Chaplin's KING IN NEW YORK is a splendid idea -- we chuckle at its conception -- though Chaplin conducts himself like a department store floorwalker more than a comedian. And Harold Lloyd's last movie seems to me to be a nostalgic conspiracy between him and director Sturges, a Last Hurrah to remind movie audiences one last time of the glorious slapstick & pantomime heritage that America was in the process of losing forever as the old clowns faded from the scene and brash lunatics like Martin & Lewis or Bob Hope took over the reins of comedy. Lloyd's film exists in several differently edited versions, but I won't call any of them "butchered", just misunderstood. By the late Forties there weren't any skilled editors around who could quite understand the cadence, the beat, the nearly-balletic timing that a great clown brought to the camera and needed the editor to highlight -- such things as double-takes, long shots of the chase and just stationary shooting when the clown is unfolding a gag. Lloyd produced a novel, a War & Peace, if you will, of vintage gags -- his editors only understood short stories or magazine articles. They grew nervous when the camera lingered on anybody or anything. But great comedy is just that -- lingering. In his final film Lloyd wants to loiter over gags silly and profound. His dawdling is cut short and the truncated comedy that follows seems at times stiff and childish. But before Harold is relegated to the dusty shadows he still pulls off much nonsense that is both genial and brassy -- not a coming attraction, but a dignified retreat back to the Land of Belly Laughs. Anyone grounded in American cinematic comedy feels abit like one of the children in the story of the Pied Piper; we wish we could go with him back into that wonderful, magical, mountain.

The Strong Man (1926)

corny is commendable

"Corny"is a word that seems to have gone out of use. Never a sterling compliment, corny meant something homespun & sentimental manufactured to manipulate our nostalgia for "the good old days". Probably the reason the word is now extinct is that people under forty don't seem to have any "good old days" to look back on. That is an issue not to be dealt with here. Rather, let us recall the corny glory that was Harry Langdon in The Strong Man. Sexless & guiless, he can muster nothing more intimidating than petulance. A true child of comedy, his white face is rather more round than Stan Laurel's but just as vacant. That face is an inconstant tabla rasa, on which external events can impress fear, joy, and love for a moment. The storyline fits Langdon like a glove; it is Evil versus Good, with Harry the Good triumphant at the end more by slapstick grace than any wit or daring on his part. You have to have a corny mindset to enjoy this movie; to wit, there are bad & bullying people in the world who deserve an antic comeuppance & extinction. If you can hold that naive thought while watching this beautiful comedy you may find yourself, as I have, actually crying through the laughter at the loving watchcare the God of comedy gives great clowns like Langdon in their most threatening pickles. The most wondrous moment of the film occurs during the rally at the end, when with barbells, cannon, and a huge fire curtain, Langdon subdues an insolent, drunken crowd. Langdon begins walking over the curtain,which is covering the writhing crowd beneath it, and suddenly dozens of hands pop through the curtain, twisting like serpents in Dante's Inferno. It is a hilarious visual gag and an apt summary of the consequences of the crowd's evil hubris. This silent gem cannot be ignored by anyone who loves cornball pantomime -- a genre apparently as dead as our ideals. Woe is us!

The Boogie Man Will Get You (1942)

Forever Boris

It surely is a cosmic snicker that Henry Pratt supported himself as a piano mover while appearing in the French version of a Laurel & Hardy film! (Pardon Us.) Perhaps Henry, or Boris Karloff as he began calling himself, gave the boys some tips on the fine art of cajoling a balky music box up a few flights of stairs. We'll never know for sure, but that helpful, neighborly, attitude was always with him, even at his most darkly sinister or bizarre. Monster, mummy, mandarin, or daffy doctor, Karloff always seemed truly puzzled and not a little grieved at the mayhem and horror that swirled around him in every film. In Boogie Man he is simply trying to support the War effort with a little harmless electricity. His slight lisp, and polite British accent, gave his utterances a benign tone. Even his evil grimace (and only Lugosi could match those melodramatic facial convulsions) somehow seem less menacing than mildly complaining, as if he were telling you about a pesky toothache. In this film he's playing for laughs, of course, but even in his starkest horror roles you can sense just a touch of amusement at himself as he chews up the scenery (or a victim.) One feels that if he were still around to spread his arms in menace at us, he might pause & sniff, just to make sure his deodorant was still working. A thoughtful murderer -- that was Boris Karloff.

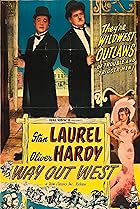

Way Out West (1937)

laughter is to die for

Laurel & Hardy have become Shakespearean, in the sense that so much has been written about them that it seems impossible to add anything non-niggling to the L&H cannon. Yet the urge to scribble, nay, to pontificate about these adorable uproarers is become an obsession. So here goes. Way Out West represents Stan Laurel with the most control he was to ever have over his own material and performance. Thus, it is useful to see what he did with that freedom and authority, and why. As a career clown Laurel had an intense relationship with laughter; it's sound, texture, nurture, and meaning. Any professional clown will tell you that laughter is addictive, whether it's a titter or a guffaw. The more you get, the more you want. And just like an addiction, there comes a time when the pleasure evaporates and leaves other, less pleasant, sensations. I find it intriguing that Way Out West is the last film the duo made where the maniacal laughing routine was used, and here it is used solely by Laurel. Hardy's melodious tenor chuckle is absent. Why so? Possibly because Laurel had finally reached that stage in his own artistic & philosophical development when he realized that laughter & deep silence are actually the same thing. Signs of deep devotion & affection. As a commercial artist he could not hazard a film that left an audience smiling and silent, so instead he brazenly laughed his film character to death, never more to giggle on screen. There would still be many more delicious moments in the odyssey of Laurel & Hardy, but their own laughter all but disappears after this film.

Diplomaniacs (1933)

remember the maniacs

Wheeler & Woolsey have been about as ill-used & forgotten as Shakespeare's Rosencrantz & Guildenstern from the play Hamlet. In the abyss of the Great Depression our country turned to its clowns for solace and distraction from calamity. They did not disappoint us, keeping us howling with mirth lest we howl with despair. In return a grateful nation has given most of them an icon sheen, reviving their films, putting their visage on posters & t-shirts, and encouraging savants, pedants, and just plain journalists, to turn their histories into myths, and their myths into history. All of them, it seems, but Wheeler & Woolsey. These two fine cuckoos have been relegated to the basement of the Museum of Comedy. Their movie Diplomaniacs shows them to be sassy, musical and self-aware comics of the first water. So why is their memory as dead as the Firestone tire? Because the American public and its media minions insist on a simplistic & single view of our great clowns. No ambiguity need apply, seems to be the sign posted on the windows of our souls. Con man & boozer? Why that's W.C. Fields, only. Wisecracker? Groucho! Silly silent girl chaser? Harpo! Wistful vagabond? Only Chaplin. We have forgotten, or never knew, that there is a common gene pool for all great clowns and their comedy. Stan Laurel chased girls in early L & H ventures. Harold Lloyd portrayed a homeless stumblebum before inventing his glass character. And so it goes. Wheeler & Woolsey practised well and wisely the common foibles of the great-hearted boobies -- they drank to excess, warbled irreverent ditties, ogled the girls, and cracked wise at the drop of a pun. But they never got a RESERVED spot in the Hollywood parking lot. Groucho, Buster, each of you can make a little room for 'em, can't you? Your brother fools? Maybe Hollywood can even make amends by filming THE WHEELER & WOOLSEY STORY, with Jim Carrey & Steve Martin. I'd pony up the bucks for that!

Sullivan's Travels (1941)

A celebration of the healing power of comedy

As a professional circus clown for twenty years,I think that Sullivan's Travels is the best, most lucid, explanation of what comedy is all about that has ever been made. Sure it's hokey, corny, contrived, and meandering. But so is all great comedy, from Shakespeare to Seinfeld! If you want your comedy to be tightly constructed, meaningful, unambiguous, and logical, then you do not want comedy at all -- you want some stuffy college professor's idea of What is Comedy for a term paper.

The glorious truth is that you cannot domesticate great comedy. It occurs on no regular basis, from no reliable source, and is accountable to no one for what it says and does. Preston Sturges wanted to make that point in Sullivans Travels and he does so exceedingly well with everything from slapstick frolics in the land cruiser to fleas in the bed to hectoring soliloquies about poverty from the butler.

Ten years before Chaplin tried to explain the same thing in his movie Limelight, Sturges tells a tale meant to both hearten and cozen us. It heartens us to know that a cynical, moneygrubbing place like Hollywood will continue to spin out comedies, because they make money. And it cozens us into thinking there is something magical about comedians. Anyone who has ever actually known or been married to a professional funnyperson knows they are by turns grumpy, lazy, tempermental, stubborn, and always insecure. Not the life of the party. But so what? They're clowns, god bless 'em, and that's all that counts.

You'll never understand the craft of humor if you don't watch, and love, Preston Sturges Sullivan's Travels!