Change Your Image

CineMage

Ratings

Most Recently Rated

Reviews

M-U-S-H (1975)

a disappointment

Saturday Morning cartoons and live-action programs swung the pendulum when it comes to satire: during some decades, these series have gotten away with a degree of satire that few live-action television series managed (such as *Rocky and Bullwinkle* and *George of the Jungle* or *G. I. Joe* during its first two seasons), but during other decades, neurotic executive and political panic reduced Saturday Morning fare to the point that tepid pablum such as *The Get-Along Gang* was the norm.

Charles Nelson Reilly's clever *Uncle Croc's Bloc* came about during one of the latter periods. Watching an episode, one could see the remnants of genuine satire and insight throughout the script, and Reilly as always managed to make the most of even the more uninspired lines, but generally, the satire had been sanitized into poorly executed zaniness and a bland mimicry of "edginess".

As part of the series' futile efforts to smuggle in "edgy" satire, *Uncle Croc's Bloc* tried to include satirical cartoon shorts -- shorts which sound good but which never had a chance to come close to their potential during that more sanitized time. These included a short about a cat on his ninth life haunted by the ghosts of his previous eight lives as they constantly try to murder him (an "edgy" idea at the time), a caveman and his pet trying to understand a dystopic modern big city (Bob Clampett or Jay Ward could have had a field day with the idea), and M*U*S*H, a parody of the popular adult live-action series M*A*S*H.

The series M*U*S*H (Mangy Unwanted Shabby Heroes) tries so hard to come across as funny that an adult viewer finds himself or herself cheering it on even though there is never a moment's doubt it will fail to provide any amusement at all. Although this cartoon series allegedly parodies the activities of Hawkeye Pierce and Trapper John from the TV series, the plots have more in common with *F Troop* -- but with none of the vaudeville talent and unapologetic shtick that made that series work.

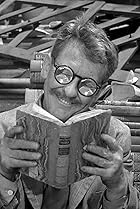

The animation is neither particularly terrible for a Saturday morning short nor above the baseline norm, and the voice actors perform their lackluster script dialogue as though they were performing honestly comedic lines. In M*U*S*H, Hawkeye Pierce becomes Bullseye, a schemer with the annoying verbal tic of laughing at his own alleged witticisms before he even makes them. Trapper John becomes Trooper, an uninspired mimicry of John Wayne characters. "Radar" O'Reilly becomes Sonar, a source of tacky jokes about near-sightedness and with an odd verbal tic of chirping just before or just after he speaks. Margaret "Hot Lips" Hoolihan becomes Cold-Lips, who sounds and behave like a rote imitation of Flip Wilson's Geraldine character. Frank Burns becomes Hank Sideburns, the mustachioed designated villain. And Colonel Henry Blake becomes Colonel Flake, for whom the voice actor inexplicably uses the sort of voice usually used in cartoons to represent a stereotypical Southern Confederate Cavalry Officer.

Watching this series in the 21st century is definitely an interesting experience, but only for the insight it gives a person into what the Saturday Morning writers and actors of the time had to work with.

Jack and the Beanstalk: The Real Story (2001)

beautiful execution of an ugly reinterpretation

Like most if not all Henson productions, this TV movie has beautifully done puppetry work, SPFX, and music. The harp's music will haunt listeners for years afterwards.

To understand Henson's take on the story, it helps to know the original story.

The original tale of Jack and the Beanstalk was first written down more than 250 years ago and is known to have existed in oral form long before then. The tale was considered a good enough tale to be referenced by William Shakespeare in his play *King Lear*.

In all its oral and written forms, the tale presented a bold trickster equivalent to the Greco-Roman creator of humanity, Prometheus, and to such Native American heroes as Coyote, Hare, and Grandmother Spider. In all these stories, the trickster heroically attempts "fire theft", i.e. liberating humanity from poverty and starvation and suffering by entering the land of the gods and stealing fire or a similar magical treasure, sometimes killing one or more guardians of the treasure in the process.

In the Greek myth, Prometheus stole fire, granting humanity the ability to cook food and forge weapons and stave off the cold and predators. In the original English folktale, Jack stole the music of the gods in the form of a golden harp, stole food for his starving family or community in the form of a cooking pot that created a meal every day, and stole the equivalent of shining fire in the goose that laid shining gold eggs. Jack also liberated his people from the god-giant's cannibalism, not unlike liberating his people from a plague that was devouring them.

However, Henson has said that he hated the original story and chose to work on it only if he could alter it. "It's a fairy tale that became part of British culture during a time when empire building and conquering other cultures was heroic" he stated (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_and_the_Beanstalk:_The_Real_Story in 2016).

Henson's film vilifies the folktale's bold trickster hero into an avaricious cad who betrays an almost clownishly innocent giant. The film then whitewashes the folktale's oppressive cannibal god-giant into a courtroom of judgmental god-giants who follow the cruel ancient idea of imprisoning, enslaving, or murdering the innocent descendants for whatever crime their ancestors may have committed, one of the principles that has been used to justify slavery and vendettas that approached genocide throughout history. "Surely in your world, if you benefit from the wrongdoings of your fathers, then you inherit the obligation to right the wrong" rationalizes a likable god-giant played with considerable charisma by Richard Attenborough as the unfortunately named character Magog.

Henson's film has been accused of political correctness and a painfully naive interpretation of serious issues such as ecology, appropriation, and reparations, but these accusations remain in dispute.

Nevertheless, after seeing what Henson did to Jack in the Beanstalk, one wonders what he would do to the myth of Prometheus or to any of the many Native American tales about this sort of theft. Perhaps he could revise Prometheus' theft of fire into copyright infringement and have the gods win a lawsuit against everyone with a stove, space heater, or book of matches?

Star Trek: Arena (1967)

excellent episode!

Once again, we have an excellent use of several of Star Trek's favorite tropes:

* a Secret Test of Character (will Kirk overcome his revulsion and blood lust?)

* a God Game (will Kirk or the Gorn Captain figure out the gunpowder weapon, all neatly laid out for easy assembly for anyone who thinks to notice?)

* an Enlightened God/Angelic Race pretending to be less than they are (the Metrons masquerading at first as violent hypocrites as part of their Secret Test of Character of both Kirk and the Gorn Captain)

* wry yet optimistic commentary on humanity ("You are still half-savage, but there is hope for you.")

Enough people have described this episode already that there is no reason for me to go through its storyline again.

In some ways, the clunky costume of the Gorn works better for the purposes of this story than would some of the more "realistic" designs in modern CGI. Accepting its flaws for the sake of the story encourages the viewer to enjoy the episode at a heightened level rather than at a dully literalist level, appropriate for a 1960s SF episode that doubles as a fable.

The Metrons and the Organians are two of the best evocations of godlike races found in Classic Trek episodes (with Trelane coming in an uncertain but respectable third), though many commentators here seem to misunderstand them.

The Metrons (said to be named after Metatron, the Voice of God in Judaeo-Christian tradition) appear at a superficial glance to be irrational and hypocritical: they tell Kirk & Company and the Gorns that they will not be allowed to fight and kill in Metron space only to place the respective captains in an arena to fight to the death with the threat that the loser's ship and crew will be destroyed. Near story's end, Kirk meets one of the seraphic Metrons, who then offers to destroy the Gorn Captain and his ship.

But it is clear with any second glance that the Metrons already knew what would happen. The arena functions less as a battleground and more as a "secret test of character" (a common enough trope in the various Star Trek series over the decades). The Metrons are no hypocrites: their actions and Kirk's response only make sense if they know from the start what will happen (just as the Organians knew the future in a different episode), and the Metrons use this opportunity to teach (test) Kirk about mercy and empathy and, presumably, teach the Gorns about what it is like to be shown such mercy and empathy.

For one thing, the raw materials for a gunpowder cannon have clearly been placed where they could be found in a condition in which they could be easily used by anyone with the cunning and verve to do so.

More importantly, when the Metron first meets Kirk, within a few sentences he makes a joke about how killing Kirk and his crew "would not be ..." pregnant pause "civilized", smiling lightly and with an amused lilt to his voice. Then, when he offers to kill off the Gorn Captain and his ship, he seems wholly unsurprised that Kirk turns him down.

Before the Metrons' intervention, Kirk was obsessed with hunting down and destroying the Gorn ship even though it would likely ignite an interstellar war; on the arena planet, Kirk admits to a further revulsion against the Gorn based solely on its reptilian appearance. Yet by the end of the episode, Kirk has progressed past his revulsion and hunger for vengeance enough to feel compassion for the Gorn Captain, to recognize that the Gorns may have had reasons for what they had done, and to hope to someday talk with and open relations with the Gorns.

None of this would have occurred if the Metrons had left them alone to incite their interplanetary war or had simply disrupted their ability to kill each other. This is not hypocrisy on the part of the Metrons but an opportunity for enlightenment (another common Star Trek trope).

Now, thanks to the Metrons' intervention, Kirk's report to Starfleet will advocate compassionate diplomacy with the Gorns and share also the wonder of having met the Metrons, rather than urge a blood-soaked war of vengeance and mammal-reptile xenophobia.

An excellent episode overall!

The Creature Wasn't Nice (1981)

You want so much to like this movie: it's a failure but an adorable failure

Yes, there will be spoilers aplenty: there is no other way to examine this work and its odd failure as a movie despite its likable moments.

This movie is a broad parody of the monster-aboard-a-spaceship style of movies that have been a part of SF cinema since its inception. The basic storyline is that a space-faring crew of Americans and a token British scientist encounter a strange new world, where they find a finger-sized "bit of goo" that seems able to choose who it likes. These are just people doing a job that involves space travel, not space explorers, but nevertheless they take the goo aboard their ship, and once there, the goo grows into a cyclopean humanoid monster. Halfway through the movie, the monster sings (and dances) that it wants to eat them. From that point on, the storyline becomes predictable as crewmembers become monster chow until the two youngest crewmembers manage to eject the monster into space.

A person wants so much to like this movie that it's hard not to wonder what went wrong. The costumes and sets would have worked well in a serious SF television series. The painted sets are almost archetypically 1960s Sci Fi. When the script works, it works despite being G-rated in its humor, a rare feat these days. The actors bring non sequitur moments of dignity, glimpsed just here and there beneath the surface, though those moments of dignity clash with the parody that the movie tries so hard to be.

In many ways it looks as though the author had been intending an absurdist work, a sort of Ionesco or Beckett theatre of the absurd set in outer space, then tried to make it marketable by disguising it as the usual parody with goofy shtick and talented comedic actors. On the other hand, this movie also looks like a cinematic fan-fic that the actors all played out as a favor to writer Bruce Kimmel, somehow shining in their individual moments despite the poor editing and flaccid plot (the actors often appear to be enjoying themselves rather than worrying about creating a movie).

Oddly, the best lines and comedic set pieces go to the least famous stars, Cindy Williams and Bruce Kimmel, while celebrated old hands Leslie Nielsen, Gerrit Graham, and Patrick Macnee end up dying at the hands of the creature. It's a little bit like the tactic used in, for example, the first Harry Potter film, in which the several unknown child stars in that film were surrounded by brilliant actors who helped make them look good (although Cindy Williams and Bruce Kimmel are far from unknown).

Williams demonstrates impressive comedic timing in her role as the Ignored Voice of Reason; for a good example of such timing, look at the gag when she screams an absurdly long scream or when she patiently (and, of course, unsuccessfully) tries to explain to the resident scientist that the monster had just finished a lounge act about how much it wants to eat all of them. But the script and editing never allow her likable moments on-screen to cohere into an actual character.

Kimmel is adorable as the clumsy, nervous Space Cadet; there's nothing particularly original or hilarious about his shtick as crew cook, crew monster bait, and crew sad sack, but he excels at the puppy dog role so well it's hard not to want to give his character a hug.

However, it becomes noticeable that, as the writer, Kimmel has made his character the hero in lieu of the more experienced actors around him: his character finds the goo (which likes him), faces the monster on his own with a brief comedic monologue, defeats the monster alongside Williams' character, and finds himself praised repeatedly by the lone female character throughout the film, who spends an inordinate amount of time with her arm wrapped protectively around him. His character "gets the girl" -- while the characters played by Leslie Nielsen, Gerrit Graham, and Patrick Macnee get eaten. This only increases the feeling that this movie is a fan-fic for Kimmel, with pals Nielsen, Graham, and Macnee gamely playing along. (I have no idea whether Kimmel is actually pals with any of these actors.) Leslie Nielsen, Gerrit Graham, and Patrick Macnee give their usual talented performances, but their performances are oddly laid back for a comedy movie: it's never quite clear whether they are playing this as a comedy or as a comedic drama. Nielsen's character has more in common with his serious-minded Commander Adams from Forbidden Planet (albeit more snarky) than he does with any of the characters Nielsen has played in recent years. (For example, there is a scene where Nielsen's character is apparently intended to be perversely glancing down Williams' neckline, but the way Nielsen plays it, it looks far more as though he is gazing down with fatherly affection on Williams and Kimmel as the frightened Designated Couple cling to each other.) Graham's character is clearly intended to be a parody Red Neck in Space figure, but he gives the character a certain angry dignity that is at odds with the parodic feel of the movie. Macnee always has fun with whatever role he accepts these days, but he shows his usual talented comedic timing even with jokes that the movie never seems to take anywhere once he's finished with them.

I would rate this movie a '9' for potential that peeps out from every corner of the movie and for the actors all bringing far more to the script than it merits, and a '4' for its failure at utilizing any of that potential, rounding to a '6' because it's just not good enough for a '7'. The only way to enjoy this work is to treat it as a group of amusing and likable set pieces and not a movie at all.

Husbands, Wives & Lovers (1978)

what could have been

This series had a wonderful theme song during the introductory credits. In many ways, that theme song is the only really memorable thing about this series.

A viewer could see the remnants and traces of a potentially strong television series buried underneath the compromises imposed by 1978 producers and censors (and the public): the adult humor tamed and sanitized until only hints of any original cleverness or insightfulness remained, the situations made "safe" and uninspired, and easy and by-the-numbers bids for audience acceptance (therefore generic and unsuccessful) creeping in within the first couple of episodes.

Hour-long comedy series have trouble gaining steady audiences to begin with, even those that work within the strictures of their era instead of trying to push the envelope without success as this one did. To their credit, the cast and crew and writers seemed to do the best that they could with what they were allowed to have.

Today, as an uncensored cable TV series, this series would have stood a chance to fulfill its potential for adult humor and commentary, but not back in 1978. Adult humor and mature commentary only work if the humor is allowed to remain adult and the commentary is not reduced by producers to pandering fluff.

Jonny Quest: Terror Island (1965)

weakest of the original Jonny Quest episodes

After reading the insights of the other IMDb reviewer, I decided to rewatch this episode a couple of times in an effort to discern what makes it the weakest of the original Jonny Quest episodes.

There is a joylessness and a by-the-numbers inertia to every part of this episode that doesn't involve Jezebel Jade. Her appearance is really the only reason this episode is worth remembering.

The comedic moments in a Jonny Quest episode almost always serve some purpose: sometimes they contribute to the plot itself, sometimes they help leaven the mood and provide variety, and sometimes they deepen characterization or a sense of the setting. But in this episode, the poorly handled "comedic moments" in this episode do none of these. Jonny's "hi-jinks" running into the water and Bandit's "hi-jinks" with the Chinese New Year firecrackers are joyless non sequiturs, coming across as strictly formula, and could easily have been cut out without any loss to the episode. They are too generic even to contribute to the exotic feel that the Hong Kong setting might have provided for a 1960s audience.

To understand where "Terror Island" stumbles, it is helpful to compare it with the other major Jonny Quest episodes involving monsters, in particular "Dragons of Ashida", "Turu the Terrible", "The Invisible Monster", and "Sea Haunt".

In both "Dragons of Ashida" and "Turu the Terrible", there is a certain elegance and verve to the designs of the monsters. Their visual appeal is strong enough that versions of them appear in the credit sequence. Furthermore, the characters have a sense of personality to them. Ashida's dragons are relatively realistic, with clear resemblances to the real world crocodile and komodo monitor. Though Turu has only nominal similarities to pteranodons, this monster is given genuine character moments, such as his clear affection for his mad monster-wrangler Deen, so that as a small child I actually felt sorry for him when he died at episode's end.

In "The Invisible Monster" and "Sea Haunt", mystery and a horrific, eerie atmosphere replace elegance and verve in monster design. The monsters themselves are somewhat cartoonish in appearance, but the ambiance conveys a potency that compensates for any flaws in their appearance.

However, the monsters in "Terror Island" are uninspired, cartoonish, and paraded before the audience almost immediately without any real build up of dread or mystery. They have no personality to them, nor any modus operandi. Ashida's dragons were intentionally bred to be angry at all times, Turu clearly loved his human companion, and the sea hunter is never depicted as evil so much as a wild animal lost, bewildered, and striking out. In contrast, there is no sense that the monsters in "Terror Island" do what they do for any reason other than plot and spectacle. They don't even seem to be under Chu's control, so their attacks seem to have no believable purpose behind them.

Another difference is the villain of the episode. There's a certain charm to Dr. Ashida's madness, heightened by the fact that he had been a friend of Dr. Quest long ago so that, for the first half of the episode, Dr. Quest struggles with his horror over how far his long-ago friend has now fallen. Dr. Ashida openly revels in his archetypal embodiment of hubris yet seems at times desperate for Dr. Quest's admiration and approval of his genius. Although Deen has little interaction with our heroes, he has moments of characterization in his relationship with Turu, and both Dr. Quest and Race try to prevent his death when they suddenly realize that Deen is racing suicidally to rescue his monstrous pet. Both villains are visually well-designed and have excellent voice acting that fits their appearances and storyline functions.

In contrast, Chu does almost nothing in "Terror Island" except brag in a particularly expository fashion, threaten Dr. Quest, then threaten Dr. Quest again, then threaten Dr. Quest in almost the same way as he has already twice threatened Dr. Quest (and threaten Race Bannon while he's at it), and then die in one of the most egregiously deus ex machina deaths to occur in the series, with nothing in characterization or storyline that might help us suspend disbelief. When he runs away from the final monster, his flight seems to be nothing more than spectacle and a by-the-numbers villain death.

Chu's visual design is just as boring as his characterization. The voice acting is flat, something that Jonny Quest episodes usually avoid. There is really nothing memorable about him, his monsters, or whatever unrevealed plot or unrevealed ambition may have motivated him.

The one saving grace of "Terror Island" is the appearance of Jezebel Jade. The episode tries a little too hard to merge Jade with the Dragon Lady from the Terry and the Pirates adventure comic strips, but otherwise, she remains the memorable and admirable Jezebel Jade.

Were it not for Jade's second and final appearance in this episode, this would be an episode most Jonny Quest fans would be happy to forget.

Highcliffe Manor (1979)

excellent potential -- all squandered by the third episode

The pilot episode -- and only the pilot episode -- of *Highcliffe Manor* was (within the constraints of late 1970s television) a hilarious parody of the more coyly atmospheric B-grade Gothic horror films of the 1950s. It starred Shelley Fabares as the Widow Blacke, a well-meaning but oblivious woman who inherits a "mad scientist" mansion set on an archetypically Gothic island off the New England coast when her husband dies in a mysterious laboratory explosion. In short order, the audience meets the dead Berkeley Blacke's cadre of fellow scientists, skulking men trying to take over the world by cloning all its leaders; Berkeley's mad scientist mistress Dr. Francis Kisgadden and her hulking assistant; a self-deluding and ineffectual "Great White" imperialist missionary just back from South Africa (in the 1970s tradition of mocking racism for easy laughs); an eerie maid whose warnings are always misunderstood by the Widow Blacke; and a group of vaguely Eastern European villagers who place a curse on the Widow Blacke for the unspecified evil which surrounds the manor.

Not long after, the audience meets the wonderfully named Bram Shelley, a "bargain basement bionic man" being constructed by Dr. Francis Kisgadden out of the remains of the late Berkeley Blacke combined with corpse parts dug up from local graves and crude cybernetic parts designed from an erector set. The interplay between Bram (played by Christian Marlowe) and Dr. Kisgadden (Eugenie Ross-Leming) was one of the strengths of the pilot and the second episode, as the amnesiac and half-human Bram, isolated in the dungeon laboratory, struggled with moments of a genuine sense of ontological angst among the volley of over-the-top jokes and cheerful cheesiness of the actors.

However, either the writers or the network had no idea how to continue the parody without enraging television censors; it was rumored that the networks did not consider American audiences intelligent enough to understand satire or parody. So instead of embracing the cheesy madness of it all or moving into incisive genre commentary or social commentary, the series quickly took the cowardly route of safely "zany" sanitized sex jokes and gelded "outrageous" humor that was outrageously tepid rather than humorous. By the time the series was canceled after its sixth episode, almost no one cared.

Unfortunately for the pilot, what seemed remarkable in 1979 has become standard or even hackneyed over the three-plus decades since, and what seemed daring on television is now commonplace, so only a historian of popular culture will recognize what made the pilot seem so delightful when it first aired.

I give the series a '6' because its '9' pilot and '8' second episode almost balance out the '1' earned by its final episodes.

Roseanne (1988)

the hilarious 1990s sitcom that helped create the 2010s culture of rage

This wildly popular sitcom centered on Roseanne, a ribald and cynically witty woman who coped with being mired in economic deprivation at the lower rungs of the social ladder with energetic humor grounded in her relentless self-absorption, her self-justifying outrage and self-pity, her pre-emptive bullying (to "get them first before they can get you because everyone is out to get you"), and her self-congratulatory hypocrisy -- with her hostility directed at her children and husband just as often as it was directed at outsiders and at any other handy target that came within firing range of her hilarious but vicious wit.

Oddly, instead of proceeding as a satire of her ethos of resentful self-entitlement and self-satisfied hostility-without-provocation, this sitcom celebrated and affirmed such hostility as a fun way of life.

Throughout the sitcom's history, Roseanne's husband repeatedly admitted he felt helplessly terrified of her, a fact which filled Roseanne with pride, and Roseanne's children fell into the habit of unsuccessfully fighting back against her while learning to submit to her violent stubbornness rather than to respect her or trust in her judgement until, by the end of the series, almost all her children had done what they could to escape her altogether.

The humor glossed the rampant negativity of the character and her way of life so successfully that many viewers were too busy laughing to think about just how petty and predatory the Roseanne character would be if she were encountered in real life instead of in a sitcom with audience laughter to hide behind. The humor and enthusiasm rationalized Roseanne's bullying and unrepentant selfishness as lovable. Only since entering syndication has it become clear that this very funny sitcom promoted and affirmed an approach to life that isn't very funny at all.

Modern Roseannes are now found across the country in the Facebook harassment scandals, the skyrocketing increase in unrepentant school bullying, the distrustful tribalism taking over much of modern life, the "stand your ground" tragedies, the hypocritical demand for exceptionalism for one's own religion or political party while refusing to extend the same rights or courtesies to any religion or political party other than one's own -- all of which continue the ethos of the Roseanne character but without the enthusiastic humor and sitcom harmlessness that made it so much more tolerable in the sitcom.

One can not help idly wondering how much future historians will point to the immensely popular Roseanne sitcom and the ethos it role-modeled for viewers as one of the multitude of causes which led to the problems of the 2010s.

Cool McCool (1966)

the witty dialog is for the adults, the goofy limited animation for the tots!

Delightful series, but let's get something out of the way from the start: you do NOT watch this for the generically Saturday morning limited animation.

Instead, you watch it for the inventive fun the writers had with the over-the-top eccentricity of the villains: witty asides of social commentary (for the time), shameless puns, parodic elements no child could possibly have noticed, and the occasional innuendo slipped past censors because who censors dialog between a green-complexioned mad scientist/sorcerer with a hat obsession and his lisping femme fatale with green hair and a ghost white death pallor? After all, does anyone think the creators of this cartoon expected the children in the audience to recognize Bob McFadden's homage to Jack Benny in the voice he gave to Cool McCool?

It's never laugh-out-loud funny, but it brings a constant smile to one's face.

Cool McCool comes from the same Saturday morning tradition as Inspector Gadget, The Inspector, and Lancelot Link: Secret Chimp, all of whom are spiritual descendants from the live-action TV series Get Smart and the film series The Pink Panther.

However, unlike the rest of them, Cool McCool has a touch of heart to him. When Cool accidentally hurts Number One, R&D techie Riggs, or his assistant Breezy, he comes across as genuinely remorseful, and he clearly loves his sapient car the Coolmobile like a pet. He has an entire segment devoted each week to his love and admiration for his father, and he introduces the segment with a song in which he regrets how often he disappoints cantankerous father-figure Number One. (Many sequences end with Number One admitting, once Cool is out of range of hearing, "I love that boy!")

In contrast, Inspector Gadget and Inspector Clouseau remain cheerfully oblivious to the feelings or needs of almost anyone else (with the obvious exception of niece Penny), while Lancelot Link and Agent 86 will lie to and manipulate their closest friends to shore up their slipping self-delusions of competence. Cool shows more affection to his car than Inspector Gadget shows to his dog Brain!

Other enjoyable aspects of this series include fun that the animation artists and the voice actors (Chuck McCann and Carol Corbett) have with the villains in ways that are easier to pick up now as an adult than they had been as children in the 1960s.

Mad scientist/sorcerer Doctor Madcap a.k.a. Professor Madcap and femme fatale lover Greta Ghoul flirt in parodic fashion -- he seduces her with "sweet nothings" by purring as he holds her in his arms, "Your eyes are like nothing! Your lips are like nothing! Your face is like nothing!"

The Owl is inspired by both Batman's foe The Penguin (in terms of bird mania) and Spider-Man's foe The Vulture (in terms of The Scheming Old Banker type and the fact that both have the means to fly). Of course, his partner in crime is The Pussycat, a Mae West-voiced version of Catwoman. Despite the superficial similarities to The Penguin, The Owl's plots seem more inspired by McCann's voicing of the character in imitation of Lionell Barrymore's scheming banker Mr. Potter from It's a Wonderful Life. (Thanks to this series, I hear Barrymore's Potter voice in my head whenever I read The Vulture's dialog in a Spider-Man comic!) (One amusing visual effect is that the two owls on The Owl's shoulders blink in unison with him.)

Hurricane Harry is inspired by the appearance of Goldfinger and the voice of Sydney Greenstreet (but with an out-of-place lisp) but otherwise has nothing in common with them. The Rattler and Jack-in-the-Box also also have voices inspired by celebrities.

The animators manage to have a lot of fun with the free-for-all deforming movements of the villains despite the limited animation. Rather than the usual static figures of this sort of animated cartoon, Jack-in-the-Box is constantly springing and swaying, The Rattler is continually coiling and slinking, and Hurricane Harry inflates and deflates even while laughing and talking.

As fun as this series is, it has become more of an historical artifact than a series that will attract many new viewers. The moments of witty social commentary have become outdated as well as turned hackneyed from being repeated endlessly in hundreds of cartoons series since this series came out. The parodic elements will probably mean nothing to modern audiences, most of whom have no idea who Jack Benny or Lionell Barrymore might be. Innuendo is a lost art today and thus unrecognizable to most modern viewers, who either never recognize it or imagine it everywhere.

As a friend pointed out to me when I showed him this series, even styles of humor wax and wane in popularity, and this style of humor, a quirky blending of vaudeville and campy absurdism and urban wit, so prevalent among live-action and cartoon TV series of the 1960s and 1970s, has not been in style for more than a decade now.

Nonetheless, for those of us who still appreciate that style of humor and who can enjoy the charms of a hero with heart despite the Saturday morning limited animation, this remains a delightful series.

The Krofft Supershow (1976)

wonderfully small-child-friendly introduction to shtick and social commentary

"The Krofft Supershows" was an anthology of cheerfully absurd television series, nothing incredibly deep but a rather sweet introduction for the single-digit age to both slapstick and social commentary.

The various series were a wonderfully child-friendly introduction to the history of shtick and vaudevillian broad comedy. Jay Robinson and Billy Barty took glorious delight in hamming up their mad scientist characters, so that I had a more skeptical perspective years later as a teenager when watching those over-serious SF films that tried futilely to be profound. Ruth Buzzi brought some of her brilliant shtick, honed in live theatre and Laugh-In, to her role in The Lost Saucer, and many of the one-shot characters were played by retired comic actors whom the Kroffts had somehow convinced to ham it up one more time on a children's television show. Most of the actors playing villains in Electra Woman and Dyna Girl were clearly having the time of their lives.

The slapstick and social commentary are important: at that age, Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton and Danny Kaye are a bit too sophisticated even in their slapstick for small children, but the slapstick comedy of the various Krofft series helped prepare a child for a later appreciation. Similarly, while the social commentary was over-obvious by adult standards (particularly in The Lost Saucer), it helped prepare a child to notice the social commentary in other programs.

Also, compared to 1980s "And knowing is half the battle" moralizing, even The Lost Saucer was comparatively subtle! Finally, I knew many teens who watched the series not only for the leisurely goofiness but because they enjoyed watching sexy Deidre Hall in her tight Electra Woman costume and watching cute blond Joseph Butcher in his half-Tarzan half-surfer dude costume as Wildboy.

Giant Monster Trashes City (2004)

brilliant satire against literalists who take all the fun out of movies!

There's nothing inherently impressive about satirizing the killjoys who self-righteously condemn suspension of disbelief -- though most people who enjoy fantasy films, SF films (or scifi flicks!), or giant monster (or kaiju eiga) movies know all too well what it is like to be harassed by these people. It's simply too easy to make lazy, cheap gags at the expense of the "mundanes" and to play to the "geek" crowd.

But this quick little short does not take the easy route. The satire is witty and spot on -- but only someone who has had to put up with literalist tirades against suspension of disbelief would be familiar enough with such people to recognize the satire. All others will be bored.

Only the dialogue, not plot or special effects, is what makes this film work so well.

The comments made by the various "talking heads" in this short perfectly mimic and lampoon the various diatribes made by priggish literalists. There is the common (and almost kneejerk) reference to the square-cube law, the same tired old complaints about the misuse of the word "mutation" in most giant monster and SF films, the uninspired and condescending dismissal of giant monsters as functioning exclusively as childish symbolism, etc.

The petty smugness of the "talking heads" is emphasized by the surreal level of petty pretension with which they argue against the possibility that the giant monster currently attacking their city could actually exist, even as they cower from its approach.

Plus points for making reference to the classic rhedosaurus! Minus points for re-using the worn-out old gag of having the sole Japanese character speak via bad lip sync.

I highly recommend this film for any fans of giant monster and/or SF & fantasy cinema! Warning: If you're not a fan of giant monsters and/or SF cinema, or if you have trouble grasping the more subtle forms of satire, this film will mean nothing to you but seven minutes of silly boredom, and you should avoid it.

Ink (2009)

Impressive But Flawed

SPOILERS AHEAD! Why did Jacob kill the other driver? The performance of Jacob in general and Jacob's causing the driving accident in particular mar what otherwise could have been a powerful, intriguing, emotionally moving film.

Via inspired cinematography and an excellent performance by Chris Kelly as John, the film presents a world in which humans are influenced through their dreams and through whispers to their unconscious minds by warrior spirits reminiscent of guardian angels and demons called, respectively, Storytellers and Incubi. A drifter (sort of a spirit lost in limbo) kidnaps a little girl's soul, so the three storytellers involved are joined by a Pathfinder, a more powerful sort of warrior spirit, called Jacob.

Unfortunately, although it becomes apparent from the dialogue that Jacob is intended to evoke the trickster sage type, sort of a Yoda or Mr. Wednesday type, with a delight in harassing or harming others in ways that make their lives better and pithy sayings-- Jacob even waxes rhapsodically about "listening to the beat" of life -- it also becomes apparent that Jeremy Make and/or director Jamin Winans are not up to the demands of the archetype. As depicted by Make, Jacob comes across not as wise but as adolescently self-righteous; his sayings make sense in the IMDb Quotes section or in print, but from the way Make's Jacob says them, they sound more like the poser "insights" of The Sphinx from the old Mystery Men movie.

More and more as the film progresses, Jacob's successes (and the storytellers' awe of him) seem to occur only because the writer made them occur and for no other reason. By the film's halfway point, the viewer begins to feel insincerely manipulated by the writer every time Jacob appears on screen instead of engaged in the film. Fortunately, Chris Kelly's performance keeps pulling the viewer back into the film.

The worst moment is when Jacob proudly sets in motion a chain of events that causes a car crash, in part to remind John he is not God and to think of others. Jacob and the storytellers rush over to check on John, but they completely ignore the other driver, clearly visible in one shot as slumped over in his vehicle. No other storytellers are seen tending to the other driver (even though numerous storytellers beyond our central three had been seen in the beginning of the film), nor does the film show any civilians tending to the other driver. The predominant impression is that the other driver is dead.

So, to accomplish his mission, Jacob exploited the other driver as a pawn, even though it killed the other driver, with no remorse and no reaction beyond proudly stating that John is too proud? The remaining flaw is the alleged happy ending. John appears to have thrown away his career needlessly (a 30 second "I'm in the hospital with my daughter" before politely hanging up would have solved everything) just because his writer told him to for the sake of an easy moral message. Second, there is no indication that his spiteful in-laws will not isolate his daughter from him again the moment she is out of danger -- after all, his in-laws had ordered John to accept he has no daughter once they attained custody of her and have basically denied him any access to her, and nothing on screen ever suggests that these people are capable of compassion or gratitude or fairness. So it's hard not to imagine John ending up impoverished, homeless, and never seeing his daughter again now that he has fulfilled his function of awakening her.

Despite all the above, this is in many ways an elegant, powerful film. One hopes that Jamin Winans will mature further as a writer/director and live up to the potential this film shows.

Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham... (2001)

morally distasteful ending ruins a beautiful film

Read the other reviews, and you will get a sense of how beautiful this film is, how beautiful its actors, how delightful its dance sequences.

However, at the end, the cold-blooded, willful, sexist, bullying father reconciles with his son by first *blaming* *him* for obeying him when he threw him out and then by *again* *blaming* *him*, this time for feeling hurt when his father hurt him. Only after this does he apologize.

This scene occurs not long after another scene in which one of the father's indirect victims whimpers that her life is worthless without having a father or father-in-law to submit to. She has a loving husband, a loving child, a loving sister, a loving mother, but she ignores all that to consider her life worthless because she has no father-in-law *to* *submit* *to*.

These scenes leave such a bad taste that most people will never be able to stomach watching the film a second time. The few who do watch it again will probably imitate a friend of mine, who watches it but always shuts off the DVD just before the final scenes and pretends they occur in a less morally distasteful fashion.

Of course, I have one acquaintance (not a friend) who enjoys the film because he thinks it is a father's right to be cold-blooded, willful, sexist, and bullying, and he dislikes the ending because he doesn't think the father should have apologized at all. So some people may actually enjoy the ending, I guess.

Alice in Wonderland (2010)

why are there so many eyes being stabbed in this film?

*POSSIBLE SPOILERS*

We went to this film with high hopes. We left without them.

The film is surprisingly mean-spirited. For example, after the Red Queen sends off to his death a talking frog who serves her, she orders to have his children served to her as a meal since she adores "tadpoles on toast almost as much as I adore caviar." However, this same Red Queen is treated as childlike and amusing, and her acts of cruelty tend to be treated like burlesque slapstick by the camera direction and musical score.

The "heroic" White Queen is similarly cruel albeit in a dainty, soft-voiced fashion. Her cruelty, since it is mostly against the enemies she shares with the protagonists, are presented in the film as heroic.

The changes from the books are erratic. One moment, The Mad Hatter is happily odd; the next moment, he pitiably whimpers to Alice (with sympathetic musical score behind him) that he feels genuine fear that he might be losing his mind.

The film often seems to be plagiarizing the imagery of the Narnia films rather than replicating the Alice in Wonderland books. For example, the dormouse behaves like a bargain basement Reepicheep, and the line-up for the "Final War" resembles the "lining up for war" scene in the first Narnia film.

The Jabberwocky is true in appearance to the famous illustrations but otherwise painfully generic.

Finally, as I heard one person at the showing complain loudly, "Why are there so many eyes being stabbed in this film?"

Peter Pan and the Pirates (1990)

the best Peter Pan

Unlike many people, before I ever saw this cartoon or the Disney version, I read both of Barry's Peter Pan books, *Peter and Wendy* and the prequel *Peter in Kensington Gardens* and watched a number of televised versions of Sir James Barry's play (including the classic Mary Martin in rerun and a well-meaning effort with Sandy Duncan and Danny Kaye).

I loved the tale of Peter Pan. For all the joyful energy in it, what I particularly loved was the witty satire beneath the hi-jinks and the tale's knowing, poignant forgiveness towards every person's childhood: "thus it will go on, so long as children are gay and innocent and heartless."

After all this, I was overjoyed to see the cartoon *Peter Pan and the Pirates*. Not only is this cartoon true to the books and the unsanitized versions of the original play, it expands upon them to turn an incisive Victorian fairy tale into a genuine fantasy work, with a world as intriguing as any ever created by Lewis in his Narnia books.

The very first episode even provides an icy elemental wizard/godling from whom Peter glibly steals treasures for his own amusement.

The one unfortunate thing about this series is that it ruined the Disney version for me. When I finally had the chance to watch Disney's Peter Pan on the big screen, I was deeply disappointed by the tepid treatment of the characters (as well as the naive racism). Disney's version paled in comparison to the original play, Sir Barry's books -- and this cartoon series.

Kung Fu Panda (2008)

just barely fails to be one of the greats

What is there to say about how wonderful almost all this movie is? The other commentators do such an excellent job, it's difficult to find anything more to add. For the first 9/10s or so, the movie has genuine heart to it, presenting characters with far more depth to them than found in most American films, live or animated. For the first 9/10s, there are no easy answers.

One of the signs of a powerful film, animated or live action, is how often the characters communicate thoughts and emotions through silence.

This is a film with many excellent moments of that silence.

Unfortunately, the final moment between the triumphant hero and the beaten, wounded, defeated, bewildered, now-helpless villain, who has been repeatedly shown to be a victim of a wounded father/son relationship that damaged him into the villain he has become, leaves a bad taste in the moviegoer's mouth. The villain is shown to be so thoroughly defeated that the hero's alleged moment of triumph becomes nothing more than a petty kick the dog moment.

The film could have and should have ended with a moment of redemption, or at least attempted redemption. Instead, it ends with a distastefully bullying joke: "Skadoosh."

Sabrina the Teenage Witch (1971)

sweet series about an ethical girl from a less cynical time

I had loved the series Sabrina the Teenage Witch as a child, and as an adult, I find it is still one of the better of the limited animation cartoon series from that time.

Unlike other magical cartoon characters since then, Sabrina was neither an idiot nor a self-absorbed greed-head (such as the hero of Fairly Oddparents). Her powers were limited only by her self-restraint, her sweet nature, and her strong personal ethics.

The episodes were more sophisticated than average for the time (a time when most cartoons tended to oversimplify the tastes and interests of children), with Sabrina having genuine moments of pettiness, annoyance, and confusion amidst the mandatory Saturday morning cartoon cheeriness.

The character also appealed to children on two levels often overlooked at the time: their identification with the Gifted Outsider, and their interest in power and wish magic. These days, we have seen the Gifted Outsider so frequently that it seems a lackluster cliché', but at the time, children's cartoons tended to encourage conformity. Sabrina hid her powers, but she used them freely albeit covertly and never expressed shame or regret over who and what she was.

I was never able to enjoy the live action Sabrina specifically because it abandoned the sweetness of the series for a hackneyed cynicism and faux edginess. The cartoon Sabrina and her aunts occasionally became angry and even fought, but the live action Sabrina and family are sometimes downright cruel, such as the time one of the live action aunts simply killed off by zapping a rival musician so she could take over her seat in the local orchestra or when for laughs a live action character ran over Mr. Kraft and apparently killing him off (since he's never seen again in the series).

The Twilight Zone: Time Enough at Last (1959)

a brilliantly painful episode

Too many people misunderstand episodes like this from The Twilight Zone.

The Twilight Zone often included episodes that were fables or morality tales in which poetic justice was meted out or in which people locked up in their own fears were confronted with epiphanies. But not every Twilight Zone episode was a fable. Some were comedies or even farces, some were commentaries on human moral frailty or humanity's self-destructive obtuseness, and some were simple horror stories.

Some were horrific, existential tales refuting the notion of a fair or just universe with an inherent morality in it, instead reminding us with moments of savage irony of those times when life, the universe, and God might seem utterly indifferent both to us and to any pretense of what is fair.

The fate of sad, bullied, kindly Mr. Bemis is one of those latter kinds of tales. It's the sort of tale which inspired philosophers such as Camus.

The tale tempts viewers to try to distance themselves from sharing in Mr. Bemis' unfair suffering. Some viewers try to find a moral that isn't there. Some viewers try to reinterpret Mr. Bemis as some sort of scapegoated example whose fate would never be their own. Many people have tried to turn this tale into a dark comedy or even a silly one (such as the amusing Futurama sketch) as a way of distancing themselves.

But Mr. Bemis isn't being punished, nor is Mr. Bemis representative of a flawed way of life that deserves suffering or loss. At most, he is an example of the many victims of the anti-intellectualism and indifference to art found throughout the United States, and his tale at first looks like a morality play when all his cloddish tormentors die towards episode's end -- until the tale reverses itself with the famous ending.

The original viewers of the Twilight Zone still remembered the Holocaust not as history but as living memory. They knew that, in real life, there are times when unfair, cruel, horrific things happen to good people for no reason.

Sometimes the Twilight Zone episodes appealed to the poetic or spiritual impulses of its viewers by presenting a world in which justice and mercy could not be stopped, not even when they necessitated an intrusion by the supernatural or miraculous to occur.

Sometimes the Twilight Zone episodes reminded its viewers of a world in which unjust and unbearably cruel things happen, for no good reason, to people who have done nothing to deserve them, and the miraculous remains absent. The tale of Mr. Bemis is one such episode.

To try to rationalize the fate of Mr. Bemis as punishment or poetic justice is to bypass the painful existential point of this episode.

The Year Without a Santa Claus (2006)

tepid Baby Boomer nag-fest using jokes that were edgy 15 years ago

I have always loved the Rankins/Bass *Year without a Santa Claus*. The scenes with Heat Miser and Cold Miser were hilarious, and Shirley Booth did a wonderful job as the voice of Mrs. Claus. So I was excited when I saw the Heat Miser/Cold Miser clip that NBC placed on youtube.

It turns out that NBC placed the only decent moments of this demeaning remake on youtube. Almost everything else disappointed when it didn't outright offend. I was tricked.

Many of the jokes seemed to be focused on telling the current generation how much better the previous generation was -- and even then, the jokes were outdated. With the complaints about life of the past twenty years and the rosy-glasses nostalgia, the focus of this version seems to be one long Baby Boomer whine.

The people behind this version are so clueless they seem to consider "goth" jokes to be cutting edge fifteen or so years too late! The jokes about "Extreme Santa" might have been clever a decade ago, but now they only show the viewer how out-of-touch these people are if they still think such jokes are clever now. The "hep African-American elf" jokes may have been funny fifteen years ago but are an embarrassment to modern racial relations. The demeaned role of women in this version is nauseating.

In the Rankins/Bass tale, Mrs. Claus is an active, intelligent woman determined both to help out the world in general and to bring her stubborn husband to his senses. In this remake, she is nothing more than a passive and obedient wife with an attractive figure. Who could have imagined wasting Delta Burke's talent playing a woman who does nothing except coo in worry? They completely disempower the character of Mrs. Claus: it isn't even her idea for the elves to go down to earth in this version! The disempowering extends to Mother Nature. In the Rankin/Bass special, Mother Nature is an awe-inspiring figure of dread, and Mrs. Claus is courteously cautious about speaking with her. In this tepid remake, Santa Claus is able to summon an obedient Mother Nature with three claps as though she were one of his harem dancing girls! The tale ends with a father guilt-tripped into destroying the hopes of hundreds if not thousands of jobs in a small town for the sake of sticking to old town values. Merry Christmas to his son who now gets a dad who will build snowmen with him, and Merry Christmas to all those workers who discover the day before Christmas they will be unemployed!

Eragon (2006)

a fun little film, not much more but charmingly unpretentious

I thought ERAGON was a fun little picture, and I have heartily recommended it to my friends -- but as a fun little picture only.

For one thing, ERAGON's depiction of dragons is light years beyond the demeaning depictions we have been subjected to in the first DUNGEONS & DRAGONS film or in the mistake that was REIGN OF FIRE! *There was no pretension to this film to get in the way of having fun!* In my humble opinion, if you go to ERAGON with the high hopes of finding another LORD OF THE RINGS or even CHRONICLES OF NARNIA, you will be sorely disappointed. However . . .

If you go to it looking for one of the best visual representations of a dragon in film history and for one of the few times an American movie has managed to present a baby monster as cute without getting nauseatingly saccharine (the baby dragon actually worked!), I think you will enjoy it.

If you go to it eager to bask in watching how some brilliant actors such as Jeremy Irons and John Malkovich can take borderline cliché' lines and somehow make them work through sheer acting gravitas, you will enjoy it.

If you go to it ready to appreciate the eye candy of some fairly sexy men and women (equal opportunity visual teases for all genders and all sexualities!), you will enjoy it.

Also, we found it fun after the film to discuss which parts seemed lifted from the LOTR novels, which from the original STAR WARS trilogy of films, which from the LOTR films, which from the EARTHSEA novels, etc.

I highly recommend ERAGON as a fun little film. Sometimes, just being fun is enough.

Mad Monster Party? (1967)

brilliant in its subtle bits, more an elegy for adults than a children's film

When I first saw this film as a child, I was fascinated by the monsters (of course!), entranced by the jazzy theme music, and angered by the dark, bleak ending. I have seen this film a number of times, and I realize now the difficulty: this film is brilliant in the side bits aimed at the adult audience but uninspired in its efforts towards the child audience. What we have here is a children's film which focuses most of its creative energy on the adults in the audience.

What we have here is an elegy for a more innocent time when monsters involved bloodsucking aristocrats and humanoid sea creatures instead of the monstrosity of the atomic bomb, a horror which in the end trumps all the undead and animalistic horrors of a far more innocent age. In the time of the Vietnam War and atomic bomb, a mad scientist creating life from corpses must have seemed almost civilized by comparison. "What kind of a monster is he?" "He's a human being." "Augh, they're the worst kind!" You can see this sense of sadness in the subtle bits backgrounding the sometimes over-obvious puns and slapstick.

In the serious depictions of the Invisible Man, Griffith is a disconsolate man driven to misery by his condition. When we first encounter the Invisible Man in this film, he must make his way past alcoholic bottles strewn about his house. Anyone who has known an alcoholic will recognize that house. The kiddies see some weak jokes about invisibility; the adults see a children's film character with hints of alcoholic despair.

When the Monster's Mate gets up to dance with the Mummy, the Monster stands up and watches, hands limply at his side, in helpless jealousy. Throughout the film, there are several moments of such subtle indications of jealousy and even devotion on his part towards her. These little bits add just a hint of pathos to what would otherwise be a stock cartoon relationship.

We get a similar sense of history with the other characters. The Werewolf is dressed like a gypsy boy in reference to the gypsy curse link in the Wolfman films, ear ring and all. Similarly, the film emphasizes the youth of the Hunchback, something usually ignored. These are childlike monsters with a childlike understanding of death, not really deserving of their final fate.

Now that I have lived long enough to have my own sense of nostalgia for a seemingly more innocent time, I enjoy the robust energy and liveliness shown by these monsters despite their being ultimately doomed by the ill will of the atomic age. The bleak ending is a betrayal for a child, but a poignant yet cynical elegy for an adult.

Captain Planet and the Planeteers (1990)

well-meaning but silly in its naivete

The producers of this series launched this series with public statements that their purpose was to encourage environmental concern, a laudable goal.

Unfortunately, they failed to take into consideration how this series undermines rather than encourages pro-active environmental awareness.

According to this series, if our pollution and other environmental follies ever become too intense, never fear, the Earth itself will manifest a superpowered goddess (Gaia) and her superhero avatar (Captain Planet) to fix it for us. So why should anyone worry about litter or misuse of nuclear energy when there is always a two-dimensional savior figure waiting in the wings to fix it for us without any real help from us beyond a token phrase about "the power is yours" (it's yours, but I wield it, and you don't have to do a thing!)?

According to this series, pollution and other environmental follies don't really come from well-meaning but shortsighted researchers and businessfolk, nor do they come from profiteering corporations for which many of us work -- they come from evil destructive cruel villainous scum, so all we have to do is defeat the bad guys and the world will be environmentally clean and pollution-free. Since our viewers know they are not evil destructive cruel villainous scum, why should they feel any sense of personal responsibility for pollution and such? Instead, they can just focus on vilifying a few evil bad guys without whom everything would be wonderful.

Instead of encouraging environmental concern, this series simplifies all the complexities underlying pollution et al. into a crude if-we-defeat-the-few-bad-guys-everything-will-be-swell perspective with reliance not on oneself but on a summoned savior figure who removes personal responsibility.

Painfullly naive.

Excellent voice actors, though, and I always found myself cheering for Dr. Blight (Meg Ryan) and her computer MAL (Tim Curry) since they often had more wit and depth than any of the ethnic stereotype heroes and their ditzy superhero.

Teen Titans (2003)

a wasted opportunity, insulting to teenagers

Let me state from the outset that I recognize and respect the changes which have to be made when a superhero comic book is translated for television or film. I had no problem with Spider-Man's web spinners being biological instead of technological. I fully understand why the film version of Xavier's School for Gifted Children is a hodgepodge of the *X-Men* title roll-calls of the past several decades. There have been enough different visions of the Superman and Batman characters that I am not surprised by the variety of interpretations in the many films and television series on these characters.

That said, this cartoon series is a demeaning take on the classic *Teen Titans* comic book title which revitalized the D.C. Comics line-up in the 1980s and 1990s and a demeaning take on the modern American teenager.

In the comic book title, the Teen Titans are thoughtful college-age teenagers who grapple with ethical uncertainties.

The cartoon turns them into anorexic anime' clichés behaving in that sort of tritely false junior high way only adults who have completely forgotten their teenage years could write, with an almost desperate pretense of hipness to it.

Robin the protégé' of The Batman is given a tolerable interpretation, although in the title Tim Drake (Robin) lives at home with his wealthy father, and Dick Grayson (the original Robin of the Teen Titans) was a college student living with The Batman.

However . . .

Raven is a shy, quiet empath with tremendous survivor's guilt and a control over the shadows of the human soul, not a poorly done goth imitation of MTV's Daria!

Beast Boy (Changeling) is a witty trickster and adopted son of one of the richest men in the world, not an emaciated Eddie Munster with all the wit of one of the Brady Bunch kids!

Starfire is a buxom, statuesque warrior princess who can fire off devastating star bolts, not a pre-pubescent anime' fairy princess flinging energy gobs like a monkey flinging poo!

Cyborg is a brilliant engineer, son of the designer of Titans Tower, not a stereotypical Black kid like every other stereotypical Black kid shown on television (at least he avoids wearing the requisite basketball uniform or mouthing the hackneyed efforts to imitate rap!)

Terra is a cigarette-smoking sexual predator and violent psychopath, not a waifish orphan girl given to collapsing into tears whenever the plot needs Beast Boy to seem like the rescuing male!

Unlike the Batman animated series or the Justice League cartoons, this cartoon is nothing but a wasted effort which trivializes teenagers as empty-headed posturers.

AVOID!

Family Guy (1999)

socially regressive, not transgressive: the anti-"Simpsons"

**DEFINITE SPOILERS AHEAD**

Some people have referred to this as part of the brilliant tradition of the Simpsons, but they couldn't be further from the truth. "The Simpsons" has (usually) been a brilliant parody of the flaws of modern U.S. society, mocking our wan acceptance of mediocrity, cleverly criticizing the unfairness of the U.S. economic system, and generally critiquing the remnants of racism, sexism, anti-Semitism, and homophobia which still taint our society. "The Family Guy" is the reverse.

"The Family Guy" imitates the taboo-breaking humor of Y2K comedy to camouflage its reactionary stance.

Skeptical? Take a look at the episode attacking gun control.

The way Peter Griffin's family treats him is the reactionary right's ideal of male privilege: he can be completely selfish, self-absorbed, violent, outright cruel to his children, and yet he is still treated as the head of the family For No Other Reason Than He Is The Father/Husband. This is not a good-hearted man who stumbles; this is an argument that merely being male is sufficient justification to dominate all others.

Lois Griffin is the reactionary right's ideal woman. No matter how much her husband puts himself before her, she remains loyal to him. She has no sense of identity beyond her roles of mother and wife. In one episode she took on feminism to promote stay-at-home-mom subservient wife values.

Stewie Griffin fits perfectly with the Dobson explanation of children. Read the Focus on the Family propaganda and you will encounter the steadfast belief that children are born evil and an eerie return of the Victorian belief that the evil must be beaten out of them. Thus Stewie promotes the idea that there are no innocent children, justifying the reactionary right's delight in corporal punishment of those younger and weaker than the average adult.

The Griffin family solution to almost everything involves violence and a distrust of outsiders. Peter happily beats up anyone who disagrees with him. Sometimes innocent bystanders are killed off for a laugh, but as long as that person is not a member of the family, no one cares.

I could continue, but I think I have made my point.

"The Simpsons" is the sort of program which points out to us how we need to improve ourselves.

"The Family Guy" is the sort of program which rationalizes excuses to remain just as lowly as we are at our worst.

A Mighty Wind (2003)

a Rorschach film: brilliantly poignant and wry for some, tepid for others

**SPOILERS**

A Rorschach film: this is a brilliantly wry slice-of-modern-absurdity for some and merely a tepid comedy with quotable one-liners for others.

To be honest, this is the sort of movie I would have found mildly boring ten years ago when I was in college. The absurdity of the characters' naive self-absorption is too low-key to evoke more than a smile; the subject matter (folksinging) is not exactly a contemporary choice for parody material; and many times the humor veers too aimlessly from clever satire (the anal retentive reunion producer) to the simply odd (the Witches Into Natural Colors) to flat efforts at "zany" surprises (the surprise denouement of one of the Folksmen).

However, in the ten years since college, I've learned that most people who pursue their dreams are just a little bit sad, and I've come to appreciate just how many disappointments a would-be artist or writer -- or anyone else with dreams -- has to swallow to keep even a few of his or her dreams alive in the world.

I've met a lot people just like the characters in this film. The brilliant characterizations by Levy, O'Hara, Guest, Shearer, McKean, Begley, and the rest of the cast are witty, knowing captures of such people. O'Hara is particularly adroit playing a middle-aged woman who has come to accept that her brief moment of fame and of passionate romance concluded more than half her lifetime ago -- hers is the most affecting performance in the film. Levy could've gotten away with nothing more than a comic cliché of a burn-out from the 1960s but instead manages to evoke a certain poignancy without falling into schmaltz. The chemistry between both these two actors and their characters brings a tear to the eye once or twice without seeming jarring or contrived.

A few times, the story is a tad too wistful about the past and takes too much delight in making the past look good by depicting the present as meaningless gloss in comparison -- sometimes the actors/writers seem to be indulging in middle-aged nostalgia for their own youth instead of telling a story about a folksinging reunion.

Still, I'm impressed (as I usually am with these actors/writers) at the way the movie combines off the wall comic bits with subtle emotional nuances in a style unique to this type of parody/commentary on human life.

You'll either adore this movie or find it merely mildly diverting, but those of us who adore it will probably want to give it a 9 out of 10!