Pieter Bruegel the Elder was an influential 16th-century Flemish Renaissance painter, whose topics were nevertheless not typical for the time period. He was more interested in common people, particularly peasants, than royals, clergymen, religious figures or noblemen. He was the first artist to portray this previously ignored population group. With masterful strokes and eye for detail, he documented the folk culture of his era and immortalized it for future generations. He was also the first to make nature landscapes as central - if not more central - than the people in it, making him the first known genre painter in history. Today, Bruegel remains beloved for the humanity of his work. While Bruegel wasn't a comic artist in the modern sense of the word, he has many strong ties to the genre. His work makes use of humorous, satirical portrayals of ordinary people, who are often crowded together in huge panoramic scenes, which resemble comic panels. Droll antics, visualizations of word play and borderline caricatural characters are omnipresent in his work. Some of his paintings and engravings even make use of sequential narratives. As a result, he was a major influence on many comic artists, particularly in Belgium on both sides of the language border.

'The Witch of Malleghem' (1559).

Life and career

Pieter Bruegel was born in 1525 in the Duchy of Brabant. His native town is still a matter of dispute. Historians guess he was either born in Breda or the village Son of Bruegel, both located in the present-day Netherlands. However, in the 16th century, Brabant was part of the Habsburg Empire and ruled by Spain. Also, Bruegel spent most of his life between Antwerp and Brussels, in what is nowadays Belgium. As a result, his work has always been more associated with Flemish/Belgian culture. Another confusing aspect about Bruegel is the spelling of his name. Variations like "Brueghel", "Breughel", "Bruegel" or "Breugel" are not uncommon.

Between 1545 and 1550, Bruegel studied in Antwerp under the apprenticeship of Pieter Coecke van Aelst, whose daughter he would marry in 1563. In 1551, Bruegel became a member of the Guild of St. Lucas. A long trip to Italy through France and the Swiss Alps between 1552 and 1555 had a profound impact on his graphical development. Like many artists, he visited Rome and studied Italian masters, but felt more awe for the local picturesque landscapes. Bruegel made numerous nature sketches before he returned to Antwerp in 1555. There he worked for painter Hieronymus Cock, who also owned a publishing company. This provided Bruegel with both a steady income as well as a means to promote and sell his engravings all across Europe. In 1563, he moved to Brussels with his wife, where he passed away in 1569.

Style

Bruegel's earliest work shows the influence of Hieronymus Bosch. The painter died a decade before Bruegel's birth, but was still in high demand, so much so that new generations of artists kept copying his originals and producing similar works featuring Hell, monsters, demons and other macabre scenes. Many of Bruegel's engravings and paintings have a Boschesque atmosphere: 'De Zeven Hoofdzonden' ('The Seven Deadly Sins', 1556-1558), 'De Zeven Deugden' ('The Seven Virtues', 1559-1560), 'Dulle Griet' ('Mad Meg', 1561), 'De Val van de Opstandige Engelen' ('The Fall of the Rebel Angels', 1562) and 'De Triomf van de Dood' ('The Triumph of Death', 1562). Gradually, he found a more personal style. He made numerous engravings and paintings depicting villages and farmers. Like a modern-day journalist, he documented their entire culture. According to art biographer Karel van Mander, Bruegel supposedly even dressed up as a peasant to interact with them in the countryside. He painted them working on the land, but also during their rare pastimes such as fairs, weddings and other festivities. Even their proverbs, sayings and children's games weren't too trivial to him.

At the time, such interest in commoners was unprecedented. Most artists before Bruegel used villagers predominantly as background characters. He made them central to his imagery. As such, his work looks like a missing link between the religion-dominated Middle Ages and the more humanist Renaissance. Even when he painted biblical or mythological themes, they were usually just an excuse to create breathtaking homages to authentic peasant life and the splendor of nature. A prime example is 'De Val van Icarus' ('The Fall of Icarus', 1558). His fall from the sky is reduced to a tiny insignificant detail. We only see two legs writhing in the water. Viewers are drawn more to the beautiful landscape and the farmer, shepherd, fisherman and sailors who all mind their own business, while Icarus drowns. In works like 'De Strijd Tussen Carnvail en Vasten' ('The Fight Between Carnival and Lent', 1559, based on a similar engraving by Frans Hogenberg), 'De Zelfmoord van Saul' ('The Suicide of Saul', 1562), 'De Kruisdraging' ('The Procession to Cavalry', 1564), 'De Prediking van Johannes de Doper' ('The Preaching of John The Baptist', 1566), 'De Volkstelling in Bethlehem' ('The Census at Bethlehem', 1566) and 'De Bekering van Paulus' ('The Conversion of Paul', 1567) the actual titles are easily overlooked. Huge crowds of people distract the onlooker. One can stare for hours at these works and still notice new details. Each person is captured in their own little moment of time. None of them are more or less important than the actual exalted theme.

'The Fight between Carnival and Lent' (1559).

Reputation during his lifetime

While Bruegel was quite popular in his own lifetime, he was not held in high esteem. Since everyday men and women were widely perceived as unimportant and uncivilized clouts, many felt he downgraded his talent. Instead of idealizing the human body, like his colleagues in Italy did, he depicted people who were rough, pudgy, boorish, even somewhat ugly. Blind people and cripples were not left out, but depicted like any other human being. Bruegel also showed commoners engaging in droll antics. They overindulge themselves with food and alcohol and are frequently seen relieving themselves in plain sight. Contemporaries nicknamed him "Peer den drol" ("Pete the turd") for depicting mankind in such an unflattering manner. People from higher classes saw Bruegel's work as confirmation of their own prejudices and laughed at the moronic slobs in his art.

'The Beggars' ('The Cripples') (1568).

Controversy

Yet the fact that he wasn't taken seriously actually worked in Bruegel's favor. Several of his works had hidden political and social messages. 'De Moord Op de Onschuldige Kinderen' ('The Massacre Of The Innocents', 1567), for instance, officially depicts king Herodes' genocide on all first-born boys in Judea. However, the bearded horseman in black, who observes his soldiers killing babies, has been interpreted as a stab at the Spanish Duke of Alva, whose reign of terror in the Netherlands instigated the Dutch resistance movement, which led to the Eighty Years' War. Even though the political metaphor isn't blatant, the painting was still a victim of censorship. Some time later, the bodies of the children who were stabbed to death were painted over. They were replaced by pieces of bread and animals, because viewers felt it looked too gruesome.

At first glance, 'De Prediking van Johannes de Doper' ('The Preaching of John the Baptist', 1566) appears to portray John the Baptist and Jesus Christ secretly speaking in the woods. In reality it seems to be a thinly veiled portrayal of a secret Lutheran, Calvinist or anti-Spanish meeting. 'Twee Aapjes' ('Two Monkeys', 1562) shows two monkeys chained to one another, with the harbor of Antwerp in the background, also hinting at a political metaphor. On his deathbed, Bruegel even ordered his wife to burn several of his works, because they could bring her and his family in big trouble.

'Massacre of the Innocents' (1566).

Posthumous reputation

After his death, Bruegel's popularity rose. Just like Hieronymus Bosch, his work was widely copied and imitated, mostly by Bruegel's own sons. Throughout the centuries many other great artists also started producing landscape paintings and scenes depicting villagers and/or proverbs: Joos De Momper, Jan Steen, Adriaen Brouwer, Adriaen van Ostade, Hans Bol, Jacob Jordaens, Jacob Savery, Abel Grimmer and others. William Hogarth made similar satirical and moralistic reflections on his own time period. Francisco de Goya's later more dark, gruesome and fantastical works also echo Bruegel's influence. James Ensor, Jules De Bruycker, Eugène Laermans, Constant Permeke, Gustaaf De Smet, Max Beckmann, Wilfredo Lam and Jacek Yerka all admired Bruegel's craft. Among the celebrities who collected his art were A.P. De Granvelle (who was the personal advisor of Dutch governor Margaret of Parma), Rudolf II of the Habsburg Empire and painter Peter Paul Rubens.

Art critics only caught up in the 19th century, when German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe praised Bruegel's landscapes. Similarly, French novelist Charles Baudelaire was also mesmerized by his paintings. Critics finally revalued Bruegel as an exceptionally gifted artist, whose work provides historians with a time capsule of 16th-century society. If not for him, much of our present knowledge about the period would have been lost. 'De Toren van Babel' ('The Tower of Babel', 1563), for instance, gives us insight into the architectural methods used in Bruegel's age. The six blind people in 'De Parabel der Blinden' ('The Blind Leading The Blind', 1568) are depicted with such intricate detail that surgeons can identify each individual's eye disease. Amazing realistic portrayals like these have made people wonder whether Bruegel was knowledgeable in these fields. It could have been that he was just an exceptionally gifted observer. Many of his landscapes, for instance, are all composites of different kinds of nature scenes. And yet none of it looks like it was stitched together. All the elements blend seamlessly into one another. Bruegel had a similar expert eye for people. Even when depicted in huge crowds: they never become a vague blur. Each person is individualized, down to their facial expressions.

'The Blind Leading the Blind' (1568).

Besides his technical merits, Bruegel was also appreciated as a great satirist and humanist. Many of his imitators merely romanticized country life and lacked the skills to elevate above caricature. Bruegel, on the other hand, almost matches a press photographer in his realism. His farmers are not just actors in costume, but accurately observed and believable human beings. They may not be the most dignified or good looking individuals around, but they are who they are. Bruegels' portrayals of simple villagers feel far more honest and moving than the sanitized portraits of noblemen made in the same time period. One of the few contemporaries who understood his art was famous cartographer Abraham Ortelius, who once wrote in his 'Album Amicorum': "In his works the truth is more important than the painting."

'Wedding Dance in the Open Air' (1566).

Prototypical comics

Bruegel was such a folk artist that it comes to no surprise that his work appealed to generations of comic artists. Several of his "crowd paintings" look like a panel from a comic strip. Viewers can see dozens of stories-within-stories taking place. People are depicted as countless little men and women. Their boorish look, along with their droll behavior, makes them similar to characters in a humor comic. Bruegel also delighted in visualizing figure-of-speech expressions, an element not uncommon in comics. He was directly inspired by fellow Flemish engraver Frans Hogenberg, whose 'De Blauwe Huik' ('The Blue Cloak', 1558) features literal metaphors of popular sayings. Bruegel made several engravings and paintings depicting proverbs, namely 'De Grote Vissen Eten De Kleine' ('Big Fish Eating The Small Fish', 1556), 'Twaalf Spreekwoorden' ('Twelve Proverbs', 1558), 'Nederlandse Spreekwoorden' ('Dutch Proverbs', 1559), 'Luilekkerland' ('The Land of Cockaigne', 1567), 'De Nestenrover' ('The Nest Robber', 1568), 'De Parabel der Blinden' ('The Blind Leading The Blind', 1568) and 'De Ekster Op De Galg' ('The Magpie On The Gallows', 1568).

The 'Twelve Proverbs' in particular is interesting, because it shows twelve separate images, juxtaposed in three rows of four. Each one has a round shape, because they were originally depicted on porridge bowls. The images were eventually cut down and combined into a panel with a framed latticework. The proverbs are all clearly framed separately from one another, yet are part of the same concept. Underneath each image the proverb is written down in old Dutch, giving the work the appearance of a text comic.

Bruegel often visualized metaphors and allegories. 'De Misantroop' ('The Miser', 1568) shows a man in a dark cloak being robbed by a dwarf who wears a globe around his body, symbolizing universal theft. Underneath the image is written: "Because the world is so unfair, I mourn in despair." This makes it comparable to a satirical newspaper cartoon. Similarly, Bruegel's engravings about 'The Seven Sins' and 'Seven Virtues' also portray abstract biblical concepts, accompanied by a moralistic text underneath each image. The works are told in sequences, which lack a narrative or distinctive chronological order, but still follow a basic conceptual theme. In the same line we have 'De Vier Jaargetijden' ('The Four Seasons', 1565), a conceptual series about the seasons. Originally made in six parts (nowadays one of them is lost), these works don't follow any particular reading order either, but the months do follow an established pattern. Whether you start in January and end in December or, as the farmers in Bruegel's age did, from the sowing in September to the harvest in August.

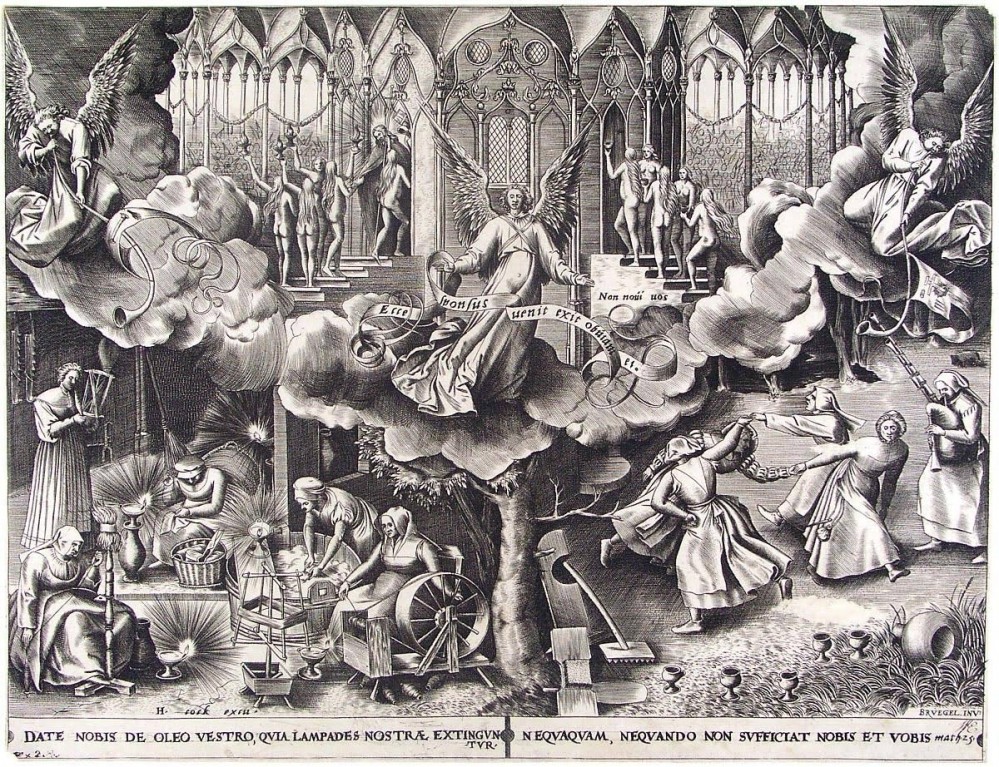

Perhaps the most striking example of sequential narrative art can be found in 'Zeven Wijze Maagden, Zeven Dwaze Maagden' ('Seven Wise and Seven Foolish Virgins', 1560). The engraving tells a clear story, based on the Biblical parable. In the left corner beneath we see the wise virgins working. Their reward afterwards is shown in the left corner above: they are allowed entry in Heaven. The right corner beneath shows the foolish virgins partying and neglecting their work. They are punished in the right corner above, standing for a closed Heaven's gate. The work is notable for actually suggesting a passing of time in clearly separated images. Bruegel cleverly frames them by conveniently placing angels, clouds and a tree stump in the appropriate places. We can not only 'read' the painting as a 'before/after' story for each individual septet, but also compare the behavior of each group with one another at the same moment in time.

'Seven Wise and Seven Foolish Virgins' (1560-1563).

Recognition

Bruegel's name lives on in several traditional Belgian festivities and parades, typically with large amounts of beer, food and actors performing in 16th-century costume. His name inspired the beer brand "Bruegel" (famously namedropped in Jacques Brel's song 'La Bière' (1968) as "Bruegel Ancienne") and the economic think thank Bruegel (2005). His name also spawned the eponym "Bruegelian", which not only refers to painters depicting peasants, but also in general people enjoying elaborate gastronomic festivities. Meige's syndrome, referring to a neurological disorder where people appear to be yawning, is sometimes referred to as Bruegel's syndrome, in reference to his painting 'De Geeuwer' ('The Yawner').

On 9 October 1926, a square was named after Bruegel in the Dutch town of Breugel in the province of North Brabant, inaugurated with a simple horizontal monument, sculpted by A.J. Kropholler. In 1996, a bronze bust depicting Bruegel, sculpted by Jan Couwenberg, was added. In 2019, to mark the 450th anniversary of his death, Bruegel also received a statue in front of the Kapellekerk church in Brussels, sculpted by Tom Franzen.

In 1985, a crater on planet Mercury was named after Bruegel, followed on 17 April 1996 by an asteroid. In 2004, the painter appeared on the 152th place in the election of "De Grootste Nederlander" ("The Greatest Dutchman") and was ranked even higher during the "Grootste Belg" ("Greatest Belgian") elections in 2005. In the Walloon version, he was voted to the 58th place, while in the Flemish version he ranked at number 17.

Legacy and influence

Together with Hieronymus Bosch, Bruegel is the first prototypical Dutch-language comic artist, whose work paved the way for similar prototypical sequential illustrators in the Low Countries, such as Otto van Veen, Romeyn de Hooghe and Willem Bilderdijk. Bruegel can be considered the ancestor of all Belgian comic artists. Hergé, Edgar P. Jacobs, André Franquin, Bob De Moor, Willy Vandersteen, Marc Sleen, Jef Nys, Gal (Gerard Alsteens), René Hausman, Yves H., Dieter Van Der Ougstraete, Kamagurka and Herr Seele have all cited him as a direct influence. Jef Nys made a fictional biopic about Bruegel's life in 1956, 'De Wonderbare Jeugd van Pieter Bruegel'. Jan Bosschaert and Guido Van Meir's satirical comic book 'Pest in 't Paleis' (1982), which is set in an anachronistic version of the 16th century, took much of its inspiration from Bruegel's work.

But Bruegel's real spiritual successor was without a doubt Willy Vandersteen, if only because Hergé nicknamed him the "Bruegel of Comics". Much like the 16th century painter, Vandersteen's comics were also folksy, comical and moralistic in nature. The 'Suske en Wiske' stories 'Het Spaanse Spook' (1947) and 'De Dulle Griet' (1967) were directly inspired respectively by 'Peasant Wedding' and 'Mad Meg'. The characters even meet Bruegel in person in 'Het Spaanse Spook' and later in 'De Krimson-Crisis' (1987). The Lean and Fat people in 'Het Eiland Amoras' (1945) are clearly inspired by Bruegel's 'De Vette en Magere Keuken' ('The Lean and Fat Kitchen', 1563) and/or 'Vette Aangevallen door Twee Mageren' ('Fat One Attacked By Two Lean Ones', 1559). Vandersteen also used a lot of Bruegelian imagery in his historical series 'Tijl Uilenspiegel' (1951-1953) and his final completed work 'De Geuzen' (1985-1990), both set in 16th-century Flanders. The latter series even replicated an engraving by Bruegel as an extra at the end of each album.

'A Fat Man attacked by Two Lean ones' (1559).

Bruegel remains beloved in all layers of society, all over the world. His portrayals of everyday men and women still move people. In Belgium, he is hailed as an artist who managed to capture the spirit of his people, an impression many foreigners tend to share. Belgian novelist Felix Timmermans (father of cartoonist GoT) wrote the book 'Pieter Bruegel, Zoo Heb Ik Uit Uwen Werken Geroken' (1928). Irish poet W.H. Auden's classic poem 'Musée Beaux Arts' (1938) pays homage to 'Landscape with the Fall of Icarus', while William Carlos Williams' 'Pictures from Brueghel and Other Poems' (1962) won him a Pulitzer Prize. The American comic artist Wolf William Eisenberg was such a fan of Bruegel The Elder that he took the final part of his nickname and used it as his pseudonym: Will Elder. René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo paid homage to Bruegel in 'Astérix Chez Les Belges' ('Asterix in Belgium', 1979) by having Astérix partake in a Belgian dinner that spoofs 'Peasant Wedding', drawn by Uderzo's brother Marcel. A Duck version of 'The Peasant Wedding' by Harry Balm appeared in the Dutch Donald Duck weekly in 1996. F'murr's series 'Les Aveugles' (1991) was inspired by Bruegel's 'The Blind Leading The Blind'. Erik Vandemeulebroucke made his own visualizations of Dutch proverbs and sayings. In Terry Zwigoff's documentary 'Crumb' (1994), art critic Robert Hughes named Robert Crumb "the Bruegel of the second half of the 20th century", because he satirized his own lifetime in a similar way. In 2015, Crumb copied a small detail from Bruegel's painting 'The Harvest' by etching it. François Corteggiani and Mankho adapted Bruegel's life into a comic book, 'Les Grands Peintres' (2015), set against the background of the Spanish occupation of the Netherlands.

Outside Belgium, Pieter Bruegel the Elder was a strong influence on Chris Berg, Cor Blok, Robert Crumb, Will Elder, René Follet, Terry Gilliam, Josh Kirby, Todd Schorr, Gradimir Smudja, Roland Topor and Jim Woodring. Neon Park gave Bruegel a cameo on the album cover of 'Sailin' Shoes' (1972) by Little Feat.