Everything is quiet at Cimarron. Nobody has been killed in three days.

— Las Vegas Gazette in the late 1870s

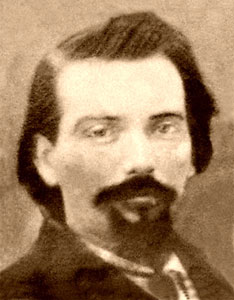

Lucien B. Maxwell

Established within an almost two million acre land grant, Cimarron, New Mexico, was built upon what was originally the Beaubien-Miranda Land Grant. In 1842 Lucien B. Maxwell, a fur trapper from Illinois, came to the area, working as a guide. His work often brought him to the Beaubien-Miranda Ranch, where he met and married one of Beaubien’s six daughters – Luz, in 1842.

Maxwell was a shrewd and lucky businessman, and in 1857, he bought Miranda’s interest in the grant and continued to develop the area. In 1858, Maxwell built a mansion in Cimarron that was as large as a city block. The Maxwell House was not only his home but a place of business that included a hotel, gambling rooms, a saloon, a dance hall, a billiard parlor, and a designated area for women of “special virtue.”

His mansion was said to have had high, molded ceilings, deeply piled carpets, velvet drapes, paintings in gold frames, and four pianos — two for each floor. Old registers included several prominent names, including Kit Carson, Clay Allison, Davy Crockett (the desperado and nephew of American frontiersman Davy Crockett), and Buffalo Bill Cody.

There were some shooting escapades at the Maxwell House in the bar and gambling rooms, but the participants were quickly kicked out, as Maxwell would not tolerate these activities. Unfortunately, the mansion was destroyed by fire in 1922, and there are no remains.

Cimarron was officially established in 1861 and was named for the Spanish word meaning “wild” and “unbroken.” The name was extremely fitting at the time, as Cimarron quickly attracted mountain men, outlaws, trappers, gold seekers, traders, and cowboys.

In 1864, after the death of his father-in-law, Maxwell bought out the five other heirs, becoming the largest landowner in the United States, and renamed the property the Maxwell Land Grant.

Maxwell’s Aztec Mill in Cimarron, New Mexico, still stands today and serves as a museum by Kathy Alexander.

In the same year, Maxwell hired a Boston engineering firm to design a three-story grist mill that he called the Aztec Mill. The mill, capable of grinding 15,000 pounds of wheat daily, supplied flour for Fort Union and distributed supplies to the area Indians, for which the federal government compensated Maxwell. Maxwell operated the Aztec Mill until 1870.

In 1866, a year after the Civil War ended, gold was discovered on Baldy Peak, and the area was filled with miners searching for their fortunes. Between the miners and the travelers along the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail, Cimarron quickly became a boomtown, boasting 16 saloons, four hotels, and numerous trading stores. The burgeoning city also gained a reputation for lawlessness, with bullets flying freely.

At one point, the Cosgrove House was hosting a “shivaree” for a newly married couple when the celebration got out of hand. The owner, Charles Cosgrove, stepped outside to run off the party-goers when the newly appointed deputy sheriff, Mason Chase, came along to see what all the fuss was about. The angry Cosgrove assumed that Chase was the instigator and shot him in the chest. A thick notebook that Chase carried in his breast pocket received the bullet and saved his life.

When Clay Allison, a notorious gunslinger, landed in the Cimarron area in 1870, he and his cowboy friends made Cimarron a regular Saturday night party place. While the barkeeps, gamblers, and dance hall girls may have appreciated their business, the rest of the citizens of Cimarron hid in terror. The cowboys punctuated their rebel yells with pops from their six-shooters as they made their rounds to area saloons, gambling halls, and dance halls. Fortifying their courage with drinks at every stop, they shot at lamps, lanterns, mirrors, and glasses and were said to have particularly enjoyed making newcomers “dance” as shots were fired at their feet.

In 1870, Lucien B. Maxwell sold his interest in the grant and all his properties for $700,000 and moved to Fort Sumner, New Mexico. The new owners of the grant aggressively exploited the resources from the gold mines, lumber, land sales, and rents.

The expectant developers opened a sales office at Maxwell’s mansion in Cimarron and waited for the customers to rush in. But they continued to wait, as faltering gold production and the threat of Indian attacks spooked potential buyers. Meanwhile, folks who had already settled on the grant were riled at the brisk way the new owners tried to collect rents.

The Maxwell Land Grant Company was not at all impressed with the rowdyism of the town and sought to overcome it with the introduction of order and culture. John Collinson, president of the Maxwell Land Grant Company, sought out Alexander P. Sullivan, a newspaperman in Santa Fe, with whom he drew up a contract for the publication of the Cimarron News and Press. The first issue appeared on September 22, 1870.

When the Land Grant Company discovered that Frenchman Henri Lambert, who was at one time, the personal chef to President Abraham Lincoln and General Ulysses S. Grant, was operating a hotel and restaurant in Elizabethtown, they induced him to come to Cimarron. The Lambert Inn, as it was called at the time, started business in 1872. Built during a time when law and order were non-existent, the saloon quickly gained a reputation as a place of violence, where it is said that 26 men were shot and killed within its adobe walls. The first question usually asked around Cimarron in the morning was: “Who was killed at Lambert’s last night?” Another favorite expression following a killing was: “It appears Lambert had himself another man for breakfast.” The Grant Company’s plan for cultivation had backfired.

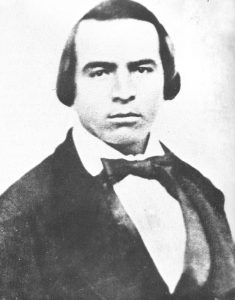

Allison and his cowboys frequented Lambert’s Inn, and their antics continued. Associated with Clay Allison during these escapades was young Davy Crockett (not the Davy Crockett of Alamo fame, but a nephew). Both Allison and Crockett were natives of Tennessee, and Crockett endeared himself to Allison because of his dislike of the black troopers stationed at Fort Union.

By 1875, Cimarron’s reputation for lawlessness was at an all-time high, and local war had broken out between the Land Grant Men and the area settlers. The new owners of the Maxwell Land Grant were busy with their attempts to evict the squatters, settlers, and farmers. The settlers, having invested their lives and money into homes and businesses, were not prepared to leave. Sheriffs served eviction notices, and retaliation began. Grant pastures were set on fire, cattle rustling increased, and officials were threatened at gunpoint. Grant gang members made nighttime raids of area homes and ranches with threats of violence to encourage cooperation with the grant owners. The local war became known as the Colfax County War, where many as 200 men lost their lives.

“Cimarron is in the hands of a mob!” — The Santa Fe New Mexican on November 9, 1875.

Parson Franklin J. Tolby came to Cimarron when it needed salvation. Enlisting with the Methodist Circuit Riders, he delivered sermons in Cimarron, Elizabethtown, Ute Park, and Ponil. Tolby loved Cimarron, planning on making it his home, and quickly sided with the settlers in their opposition to the land grant men. He was very open about his opposition, saying that he would do everything that he could to stop the land grant owners. But, on September 14, 1875, the 33-year-old minister was found shot to death in Cimarron Canyon, midway between Elizabethtown and Cimarron. The settlers immediately suspected the Grant men, as robbery was not the motive because the minister’s horse and belongings were not taken.

Rumors began to circulate that the new Cimarron Constable, Cruz Vega, was involved in the murder. On the evening of October 30, 1875, a masked mob, led by Clay Allison, confronted Vega. Though the constable denied having anything to do with the murder, the mob pummeled and hanged him by the neck from a telegraph pole.

On November 1st, Francisco “Pancho” Griego, Vega’s uncle, along with Cruz’s 18-year-old son, began threatening the townspeople in response to Vega’s death. Looking for trouble, they wandered into Lambert’s Inn. Allison was in the saloon, and Griego accused him of being involved in the hanging of Vega.

Griego began fanning himself with his hat in an attempt to distract Allison while he drew his gun, but Allison was not fooled and quickly fired two bullets killing Griego. The saloon was closed until an inquiry could be held the next morning, where Allison was found to have shot in self-defense. According to local accounts of the day, the saloon closing was the most unfortunate aspect of the whole incident. The reign of terror in Cimarron continued, and the town was out of control. Violence, lawlessness, and apprehension fed the residents, and many packed their belongings and left. At one time, guards were posted at all entrances to Cimarron, and no one was allowed to leave town without the anti-grant vigilante’s permission. By November 9, 1875, the Santa Fe New Mexican informed the public that Cimarron was in the hands of a mob.

Supposedly, Cimarron was under the control of Davy Crocket [nephew of the more famous Texan]. Crockett, along with his ranch foreman, a mean customer named Gus Heffron, were regulars at the bars and gambling halls. Though the 23-year-old Crockett was a little arrogant, he was well-liked until the night of March 24, 1876, when he got drunk and turned deadly. According to the story, Crockett, Heffron, and a man named Henry Goodman had been making the rounds in Cimarron that evening. Ready to call it a night, they stopped at Lambert’s to pick up a bottle of whiskey for the road.

As Crockett started out of the saloon, he had trouble opening the door because someone was trying to open it from the outside, which made the drunken Crockett angry. When he finally got the door open, he faced a soldier from the U.S. 9th Cavalry, the black cavalry unit known as Buffalo Soldiers.

Crockett was said to have pulled his gun and killed the man, then turned his gun on three more black troopers at a card table in the bar, killing two of them. Crockett and Heffron ran out of town on foot because their horses were stabled in a barn where the Buffalo Soldiers were camped. Crockett insisted that putting uniforms on former slaves was adding insult to injury. Appearing before the justice of the peace, Crockett was acquitted of the murders because he was drunk, the court fining him just $50 and court costs on a reduced charge of carrying arms.

After getting away with the murders, Crockett became even more arrogant and his antics intolerable. Over the next several months, he and Heffron ran roughshod over Cimarron riding their horses into stores and saloons, firing their guns into the air and ceilings, and forcing people at gunpoint to buy them drinks.

In a saloon one day, the two forced Cimarron’s Sheriff Rinehart to drink liquor until the lawman finally passed out. Tired of the two bully’s antics, Sheriff Rinehart deputized Joseph Holbrook, a Cimarron-area rancher, and John McCullough, the town’s postmaster, to go after them.

On the night of September 30, 1876, the three men, armed with double-barreled shotguns, hid near Schwenk’s barn. About 9 p.m., Crockett and Heffron approached the barn on horseback when Holbrook revealed himself and told the two to raise their hands. Crockett just laughed and told Holbrook to go ahead and shoot, and much to Crockett’s surprise, Holbrook did just exactly that.

Sheriff Rinehart and McCullough also fired blasts at the two men, startling their horses, who bolted and galloped a quarter mile or so north across the Cimarron River. Heffron, who was not hurt badly, kept on riding but Crockett’s horse stopped on the other side of the river. Crockett’s hands were locked in a death grip on the saddle horn and had to be pried open.

A short time later, Heffron was arrested but escaped on October 31, 1876, into the Colorado mountains, never to be seen again.

While this story is the one most often told, another version is held by the Crockett family descendants. In response to an article that appeared in the Albuquerque Tribune in 1976, a Crockett descendant responded with a different version that has been passed down through the generations. According to Andrew Jackson Crockett, a nephew of Davy Crockett, Rinehart wanted Crockett’s horses for his own use and accused Davy of being a horse thief. Afraid to arrest Crockett alone, Rinehart asked the cavalry to arrest him. When four Buffalo Soldiers confronted Crockett, one of them drew a gun and Davy killed three of them.

Later, Andrew Crockett said that Sheriff Rinehart, along with another man, lay in ambush for Davy and, one day, as he was leaving town, shot him in the back. Crockett was buried in the Cimarron cemetery, but, for years, no marker existed, and the grave has long been lost. Today, another marker has been erected; however, it is unknown if it was placed on his actual burial location.

The St. James Hotel (formally Lambert’s Inn, was host to such notables as Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, Jesse James, Black Jack Tom Ketchum, Annie Oakley, Buffalo Bill, Fredrick Remington, Governor Lew Wallace, and writer Zane Grey.

In 1880, a hotel was attached to Lambert’s Inn, and many well-known people stayed there over the years. These included such names as Annie Oakley and Buffalo Bill Cody, who was a goat ranch manager for Lucien Maxwell for a short time. Reportedly, Buffalo Bill met Annie Oakley at the hotel, where they planned his Wild West Show. Other notables included Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, Jesse James, train robber, Black Jack Tom Ketchum, General Sheridan, artist Fredrick Remington, Governor Lew Wallace, and writer Zane Grey. The Hotel and Inn were later renamed the St. James, which is still in operation today.

When gold production started to slow in the early 1880’s Cimarron’s population dwindled, and in 1882, it lost its county seat status to Springer.

The Colfax County War continued until the Supreme Court of the United States upheld the survey in 1887, which legitimized the Maxwell Land Grant Company. Abandoned by their government, many of the homesteaders bought or leased their places, but many just gave up and left. The Land Grant Company continued its exploitation of the many resources of the grant, and it thrived for several decades. To this day, conversations by the locals regarding the Colfax County War will still prompt serious debates and heated conversations.

When Henri Lambert’s sons replaced the roof of the Lambert Inn in 1901, they found more than 400 bullet holes in the ceiling above the bar. A double layer of heavy wood prevented anyone from sleeping upstairs from being killed. Today, the ceiling of the dining room still holds 22 bullet holes. Henri Lambert died in 1913.

In 1905 the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain, and Pacific Railroad built a spur line to Cimarron and Ute Park, causing the old town to come to life once again. Real estate investors erected hotels, and stores and sold lots and homes as people arrived on the rails.

Fred Lambert, the son of Henri Lambert, restored the Aztec Mill, which is now a museum operated by the Cimarron Historical Society. Fred Lambert was the youngest Territorial Marshall in New Mexico, sworn in at age 16, and held many law enforcement positions during his long career in Cimarron.

In 1985 the St. James Hotel was restored, and the old saloon, which is now used as the hotel’s dining room, still holds the original antique bar, as well as twenty-two bullet holes in the pressed-tin ceiling. In the hall of the hotel is a plaque that commemorates Clay Allison and the roster of 19 men he was said to have killed.

The hotel is open year-round, with 13 historic rooms named for the famous and infamous people who once stayed there. An annex was also added to the hotel that houses an additional 12 rooms.

The only monument to Lucien B Maxwell is a primitive concrete folk-art sculpture, where Maxwell sits facing the west and looking restless with a rifle in hand. However, a curator of the Aztec Mill, Buddy Morse, tells a story that the statue was actually built for Henry Springer. However, when the artist presented it, Henry didn’t like it and stated that statues were to be built for people who were dead, so, between the two of them, it was decided that the statue would be of Maxwell instead.

Schwenk’s Hall, once a gambling house and saloon in the 1870s, is now a private residence and a gift shop. Within the residence is a plaque embedded in the wall that notes, “It was here that Coal Oil Jimmy (a stagecoach robber from Elizabethtown) and Davy Crockett won $14,000 bucking Faro.”

While the owners were renovating the building, they discovered a mysterious tunnel that runs from beneath the house to a point beneath the garage, which may have once been the saloon and gambling den. One of the most interesting historical sites is the Cimarron Cemetery which continues to house many of the historical figures of their time. In the Lambert Family plot, surrounded by an old wrought-iron fence, rests Henri Lambert, who died in 1913, marked by a flecked black tombstone. Lying next to him, with a matching marker, is Mary Elizabeth Lambert, who died on December 8, 1926. Sitting sadly in another plot away from Henri is the crumbling white tombstone belonging to another Mary Lambert, Henri’s first wife.

Davy Crockett is buried in the Cimarron cemetery and a “new” rough wooden marker has been placed, though probably not on the exact spot where his remains were buried. Originally, Crockett’s grave had a rough, wooden marker made just after he was buried, but later, family members removed it with plans of replacing it with a more appropriate marker. Sadly, the new marker never arrived. In years before, there were a few old-timers who knew the whereabouts of Crockett’s unmarked grave. But now, they, too, are buried in the cemetery. When Fred Lambert, Henri’s son, was still alive, he said that the grave was halfway between Reverend Tolby’s grave, marked by a handsome monument, and the Lambert family plot.

Reverend Tolby was shot near Clear Creek in 1875. His murder was one of the initial instigators of the Colfax County War. His tombstone has been replaced with a new one, but the original tombstone can be seen at the St. James Hotel.

Sitting about a half-mile west of the St. James Hotel is an old grave that is said to possibly be that of Cruz Vega, who was killed by Clay Allison and a lynch mob on October 30, 1875.

Today, Cimarron is a quaint mountain community that is called home to about 900 people.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated September 2022.

Also See:

The Largest Land Grant in History