All hail the hen! Chickens were revered for centuries before they were food

The birds were initially viewed as exotic animals.

Chickens' first relationship with humans may not have been as a platter of wings or a pair of tasty drumsticks. Researchers have found that people initially saw these now-ubiquitous birds as exotic, and they venerated and even worshiped them.

These first domesticated chickens weren't the hefty, fast-growing birds of today. They would have been about one-third the size of modern chickens, and their striking coloration and distinctive noises likely led people to view them as mysterious and exciting novelties rather than as potential meals, according to a new study. In fact, approximately 500 years elapsed between the time when chickens first arrived in Europe, and the time when they began to be used widely for food.

In other words, eating a chicken in central Europe in 500 B.C. might have been the equivalent of chowing down on a scarlet macaw today.

"Chickens, at first, are this amazing thing," said study co-author Greger Larson, the director of the paleogenomics and bio-archaeology research network at the University of Oxford in England. Whereas people today scramble to acquire "whatever the Kardashians have," thousands of years ago "that would have been a chicken," Larson told Live Science. "That's what everyone wanted."

Related: After a Chinese zoo covered up a leopard escape, 100 chickens are searching for the big cat

The mysterious origin story of chickens

Around 80 million chickens (Gallus domesticus) exist on Earth today. In the U.S. the typical chicken raised for meat will live only six weeks before slaughter, and a laying hen will get perhaps two to three years of life.

But before there were domesticated chickens, humans became acquainted with their wild ancestors: red junglefowl (Gallus gallus) from Southeast Asia, where the birds carved out a niche eating fruit and seeds, particularly in dense forests of bamboo. The story of how these jungle birds became one of the most popular foods on Earth has murky origins. That's because archaeology in heavily forested Southeast Asia is challenging, and archaeologists haven't always paid close attention to tiny artifacts like chicken bones. What's more, chicken bones easily sink down into the ground or are disturbed by mammals' digging, human construction and other disruptions, said study co-author Joris Peters, a zooarchaeologist at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This means that soil layers in which chicken bones are found may not accurately represent the age of the bones, Peters, Larson and their colleagues reported in two papers published Monday (June 6): one in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and the other in the journal Antiquity.

The voyage of the chicken

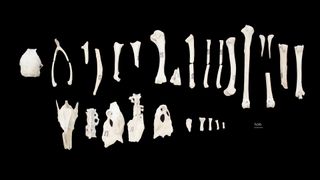

This research involved more than a decade of re-measuring and analyzing previously discovered chicken bones, as well as directly radiocarbon-dating 12 bones from 16 sites in Europe to track the chicken's spread out of Asia. The findings of both studies revealed that chickens were domesticated far more recently than previous estimates suggested. For example, one set of purported chicken bones from China dating to 10,000 years ago turned out to be from pheasants, Peters told Live Science.

In fact, humans and chickens have probably been associated for only about 3,500 years, Larson said. By about 1500 B.C., people in southeastern Asia began dry-cultivating rice and millet, a process that involved clearing areas of forest and planting fields that erupted with grain all at once. This would have attracted red junglefowl, and people probably found these colorful birds very endearing.

"They're very easy to tolerate, and they're very good-looking," Larson said.

As junglefowl came to rely on humans for food, the domestication process kicked off. Around 1000 B.C., domesticated junglefowl — what we now know as chickens — spread to central China, South Asia and Mesopotamia, probably along similar trade routes to the Silk Road, which would become more well-traveled around 200 B.C.

Sometime between about 800 B.C. and 700 B.C., chickens reached the Horn of Africa as part of a burgeoning maritime trade. Greek, Etruscan and Phoenician sailors probably spread the birds throughout the Mediterranean — chickens landed in Italy by about 700 B.C. and made it to central Europe between about 400 B.C. and 500 B.C. Interestingly, many chicken skeletons found in Europe from between 50 B.C. to A.D. 100 were associated with burials: Men were often buried with cockerels, and women with hens, and these chickens were likely important to the people with whom they were buried, Larson said.

"These are older birds, their individual birds," Larson said. "They matter to their society."

From pedestals to platters

Chickens' transition from exotic and venerated bird to food likely occurred with the rise of the Roman Empire in Europe, where eggs became popular as a stadium snack, Larson said. The first evidence of widespread chicken consumption in Roman-controlled Britain dates to around the first century A.D. It's unclear how the shift occurred, Larson added, but it's possible that having chickens around for centuries made humans reevaluate their relationship in a more practical light.

"Familiarity breeds contempt," he said.

Future archaeology will likely help refine the chronicle of chickens, Larson said, especially in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands, where evidence has been lacking. New findings could reveal more about how chickens conquered the globe — and changed human society in the process.

"The bird's management and domestication helped to sustainably expand human subsistence over time," Peters said. "In retrospect, the domestication of the chicken proved very useful for cultural developments throughout the wider region, as domestic flocks could easily be taken on sea voyages, either as provisions or, ultimately, to raise chickens in newly occupied areas."

Originally published on Live Science

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.