The 2nd Generation Ford Mustang

1974 – 1978

In order to more fully appreciate the evolution of the Ford Mustang, it is important to understand the events that caused its evolution in the first place. The old cliche “necessity is the mother of invention” rings true when it comes to the creation of the second-generation Mustang, but said necessities weren’t just a bi-product of changes within the Ford Motor Company, but rather changes that were taking place around the world as well.

The creation story of the “Mustang II” began nearly twenty-five years before Ford officially unveiled the second-generation Mustang in August 1973. For those keeping score, it could reasonably be argued that such a declaration would take us back to a time before anyone had heard of Lee Iacocca or the Ford Mustang in any form….and you’d be right.

However, this particular Mustang – the Mustang II – is the direct bi-product of events that started taking place in the early 1950s before culminating with the creation of the 2nd generation Mustang some 20-plus years later, which is why we begin our narrative there.

In the 1950s, soldiers were returning home from Europe after fighting overseas in the war. These soldiers, many of whom had remained in Europe for a time after the war officially came to an end, were either bringing automobiles back with them from overseas or were looking for affordable, foreign compact cars in the United States similar to those they’d found in Europe.

While not much consideration was given to filling this need on the domestic front initially, this increased demand for “small-and-affordable” automobiles became a growing concern for American automobile manufacturers. Chevrolet recognized a niche market for a two-seat sporty roadster – the Corvette – that would appeal to soldiers who had developed a fascination with Mercedes Benz and Porsche, but at a price point that left people looking for something else entirely.

Cars like the Volkswagen Beetle became synonymous with affordability, and by the late 1950s, the brand had established itself as a significant part of the American automotive landscape. Ford, for its part, began the development of the Ford Falcon in the late 1950s. When it was introduced in 1960, the car sold incredibly well, proving beyond any doubt that Americans were looking for small, budget-friendly automobiles.

By 1966, the Ford Falcon had grown appreciably in-size, moving from compact-and-affordable to more of a mid-size market. Once more, European and Asian imports, especially cars built by Japanese manufacturers, once more accounted for a significant percentage of U.S. auto sales.

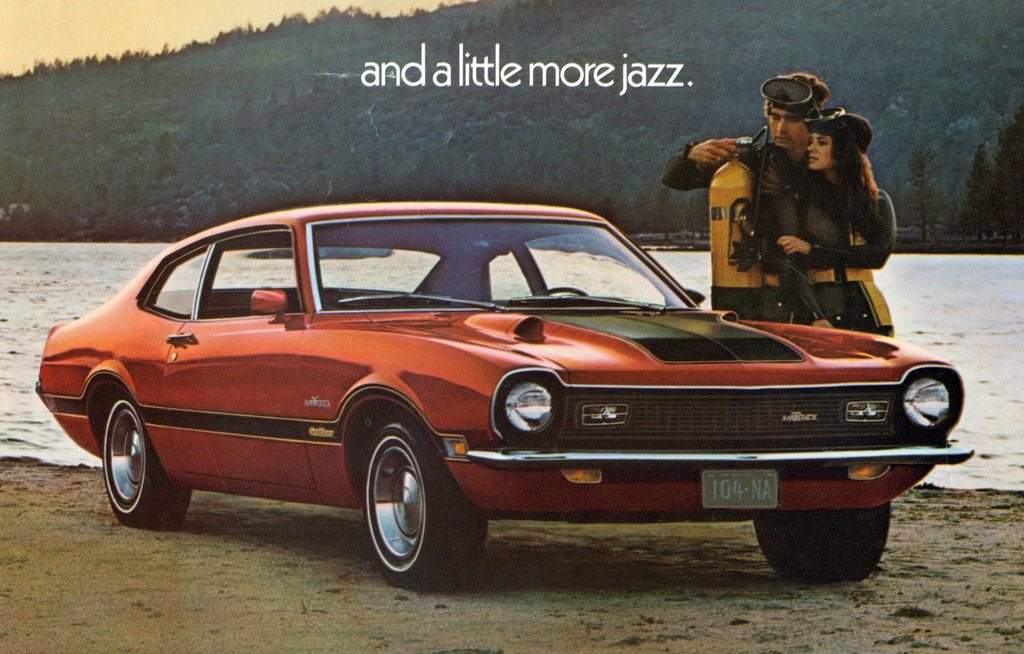

As before, Ford designers returned to the idea of a compact automobile and began leveraging the existing Falcon platform as a baseline from which to develop a small, affordable automobile. By 1969, a new Ford compact, the Maverick, was ready to make its debut and became commercially available as part of Ford’s 1970 model year lineup.

While more compact than the Falcon, the Maverick was still larger, and more expensive than, many of its import counterparts. While the Maverick found some success nationally, Ford was back to work on developing an even more affordable automobile.

In September 1970, they introduced the Ford Pinto. Upon its introduction, the car became an overnight success, with 1971 sales of the highly-affordable Pinto topping 352,000 units. Each car, which sold for less than $2,000 brand new, had filled the niche that the American public had been clamoring for. When the Pinto sold a massive 480,000 additional units in 1972, Ford knew they’d struck gold.

In contrast, sales of the Ford Mustang in 1972 had plummeted to just 125,813 units, which was the worst sales year for Mustang for three years running. Sales trends indicated that the popularity of the Mustang was on a continued decline since the 1969 model year, when Ford had sold a total of 299,824 units. In 1970, sales had dropped to just 191,239 units, and in 1971, just 151,484 units.

While some blamed the decline on Ford’s discontinuation of the Shelby GT350/500 line of Mustangs, there were others who were recognizing the Mustang for what it was – a high dollar, gas-guzzler that had gotten bloated in size and irrelevant with age.

Interestingly, Lee Iacocca had argued extensively that the Mustang needed to be downsized. In November 1969, he addressed the downsizing of the Mustang at a management meeting with Ford’s top brass. In a conference in West Virginia, Iacocca vocally chastised the direction the Mustang platform had taken since he’d first developed it in the early 1960s, and convinced the team of executives that it was time to build a new, small, sporty car.

According to author Gary Witzenburg, the meeting resulted in “top-priority plans to build a sporty small car for the 1974 model year based on…the Maverick shell.”

At the conclusion of that conference, it was decided that two programs would be introduced. The first, which was code-named “Ohio”, would be developed around the existing Ford Maverick platform with a planned production start of 1974. The second, code-named “Arizona”, was established. This second would be centered around developing an upscale version of the Pinto with a planned production start of 1975.

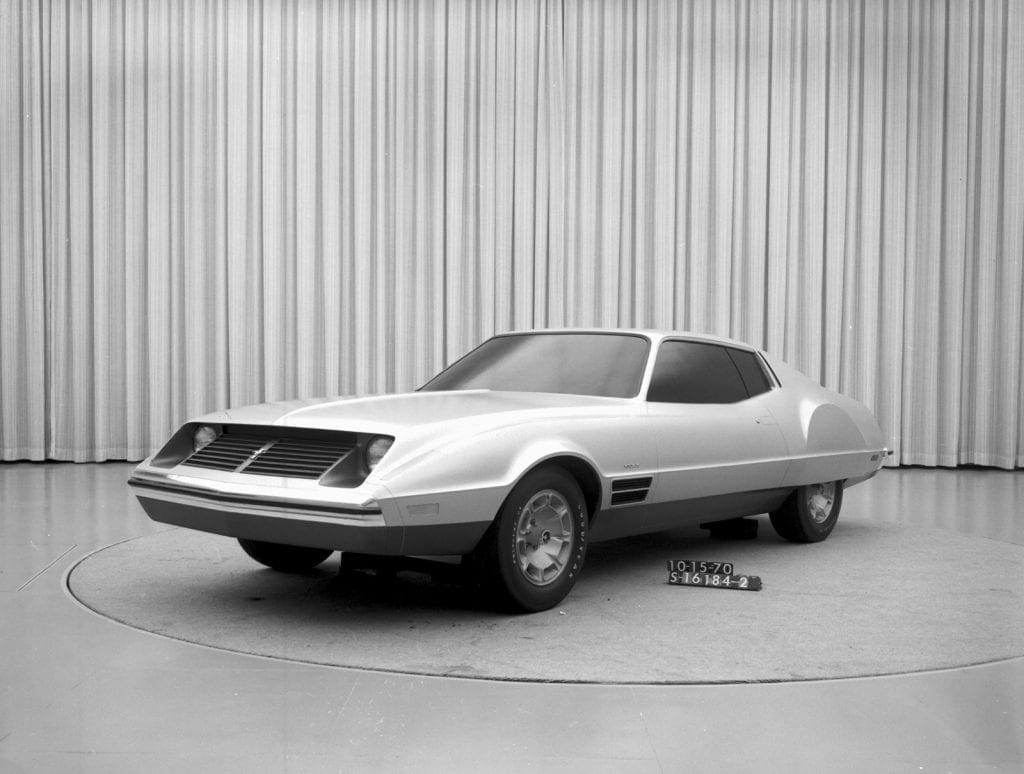

Given its earlier planned production start, it looked like the larger “Ohio” vehicle might become the next evolution of the Mustang. This car, which had a hefty 103-inch wheelbase, certainly had design elements that lent themselves to the spirit of the earlier Mustangs.

Both programs were turned over to Nat Adamson, manager of advanced product planning. He recalled that the Maverick-based car was initially favored. “(the Maverick) then seemed like a very small car to us, especially when we compared it to that year’s much bigger and longer Mustang. And the Maverick was selling very well at this time.”

However, everyone’s thought process behind the new Mustang started to shift when Lincoln-Mercury began importing their V-6 power Carpi into North America. The Ford Capri (as it was marketed in Europe), which quickly garnered the nickname “the European Mustang,” had made its European debut in London in December 1968. The car became a major success in Great Britain (so much so, in fact, that the car was marketed in Britain as “the car you always promised yourself.”) and West Germany within a year of its introduction.

Mercury began importing the German-made version of the Capri into the United States for the 1970 model year. That first model-year car was considered underpowered by some, equipped with the same 1.6-liter four-cylinder engine as the Pinto, but sales of the sub-compact automobile took off, setting records and proving once more that really small automobiles were not a passing fad.

Ford executives revisited the two development programs in July 1971 and elected to discontinue the development of the compact “Ohio” prototype in favor of moving forward with the smaller “Arizona” program. Nat Adamson, the advanced product planning manager who had led the Arizona design team from its inception was promoted to light car planning manager and was put in charge of developing the next-generation pony-car platform. Production of the new car was slated for July 1973.

From the start, the two directives that Lee Iacocca insisted upon with all parties involved in the development of the new Mustang was that this new Mustang be ready for the 1974 model year and that the car would be a “little jewel.” Iacocca knew that in the eyes of automotive manufacturers, small cars often equated to cheaply made cars. He wanted the new Mustang to be an upscale small car that would rival anything the competition – either foreign or domestic – had to offer.

Iacocca’s “little jewel” would be a four-cylinder, well-appointed-but-still-affordable automobile that exuded quality in its appearance, its fit-and-finish, its ride quality, and in all of its creature comforts. The car needed to handle well, be responsive to driver commands, yet offer minimal road-noise, vibration, or harshness during normal driving conditions.

Initially, Iacocca turned to Gene Bordinat’s studio to lead the design/styling for both the Ohio and Arizona iterations of the new pony car. Bordinat’s studios struggled to conceptualize a design that excited any of Ford’s top brass, including Iacocca. Part of their issue was that Bordinat’s team was instructed to downsize the design while working to integrate Ford’s existing inline six-cylinder engine. This engine was too long for any conventional design, and so early renderings from Bordinat’s studios depicted a car with an excessively long hood. Additionally, Bordinat and his team were outspoken proponents for the development of a single body style for the next-generation Mustang.

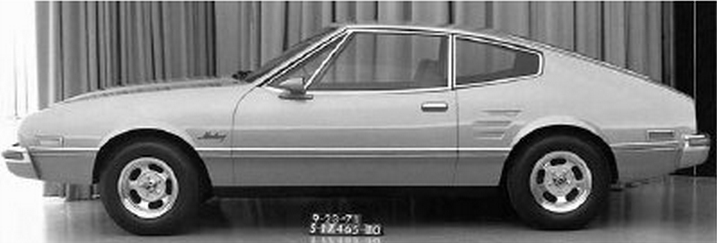

Given these early misgivings, Iacocca turned to Alejandro de Tomaso and his famed Ghia studios in Turin, Italy to assist with getting the design of Ford’s new pony-car back on- track. Two Ghia prototypes (a fastback and a notchback coupe) were developed. Iacocca was very impressed with the conceptual designs that Tomaso’s team had rendered. They became the baseline from which Ford designers would develop and evolve the next Mustang’s overall look.

Even with these designs now in-hand, Iacocca met resistance from many of Ford’s executives, as well as continued resistance from Bordinat’s design studio regarding the development of a convertible variant of the next-generation Mustang. Many argued that dwindling sales numbers of convertible models across the board justified eliminating a convertible option even at this early stage.

In terms of developing a single design, nobody – not Bordinat’s team or Ford’s top brass – was ready to decide whether a fastback or a notchback platform would evolve beyond the early clay mockups that Bordinat team was currently working on.

In August 1971, Iacocca directed Bordinat to organize a design competition to help determine which design package(s) would ultimately be used once the Mustang moved from prototype to pre-production. Much like the first Mustang before it, four teams were assembled to develop a fully realized model of what the next Mustang should look like. For the next three months, these teams would work in earnest on their design with the intent of presenting them to Iacocca in November of that year.

Upon initial presentation, it was decided that the design created by Al Mueller’s Lincoln-Mercury Studio was the winner. Their design, a sporty-looking fastback, incorporated a unique fusion of compact and sporty into its design.

Seemingly, the debate was over – and the fastback won.

However, upon further evaluation, Iacocca was drawn-in by the notchback design that had been presented by Don DeLaRossa’s Advanced Design studio. The notchback had been directly inspired by the Ghia prototype and reminded Iacocca (and many others) of the original Mustang. He found himself once more struggling with the reality that he had two viable designs – and he wasn’t prepared to part with either one.

And so it was that in February 1972 – with just 16 months left before production of the next-generation Mustang was scheduled to start – that Iacocca surprised his designers with a direct order to put DeLaRossa’s design back into the development process alongside the fastback. Around that same time, another decision was made to turn the fastback’s rear roof into a hatchback.

Following the directives that had been laid out by Lee Iacocca at the start of the car’s development, Mustang engineers Bob Negstad and Jim Kennedy developed a U-shaped, isolated subframe for the front of the car that was specifically designed to eliminate noise, vibration, and harshness (NVH). The subframe assembly, which became known as the “toilet seat” around Ford’s engineering department, was developed to absorb engine vibration and road shock before they could be transferred to the cockpit of the automobile.

In addition to the “toilet seat” subframe assembly, Negstad and Kennedy installed extra rubber insulation throughout the chassis and a unique sound-deadening barrier which was specifically designed to fuse to the car’s floorboard by “melting” during the paint baking process.

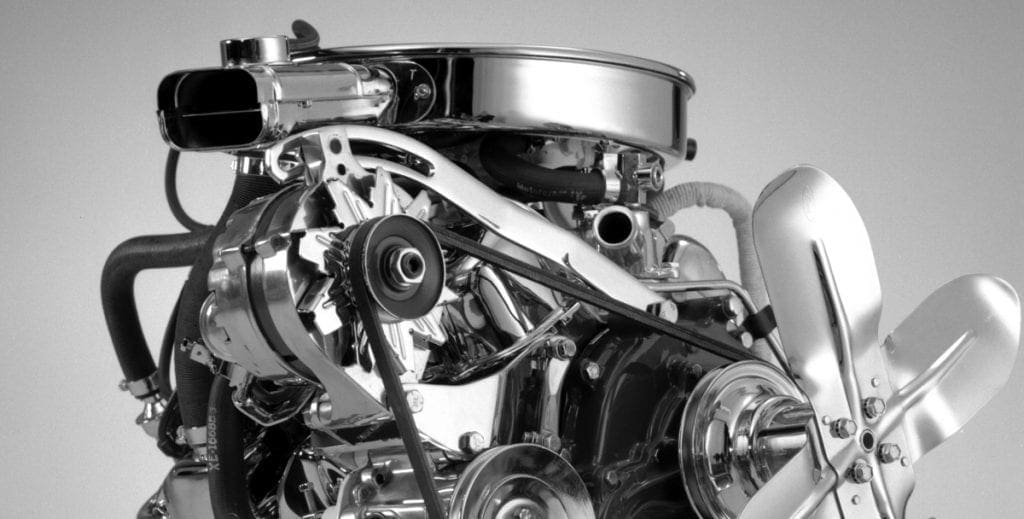

Recognizing that this new Mustang would be competing with a number of other compact, and even ultra-compact automobiles, Iacocca insisted on the installation of an 88-horsepower, 2.3L, inline SOHC four-cylinder engine as the car’s standard power plant. Iacocca recognized that this smaller engine setup would be a notable departure from the large-horsepower engines that Carroll Shelby had introduced as part of his GT350/500 program, but in keeping with the original vision that Iacocca had for the Mustang as early as 1960, the return to a smaller power plant made sense. An optional 2.8L V6, boasting a slightly more robust 105-horsepower was also offered as an optional upgrade.

Ford executives were understandably concerned about how well the new Mustang would be received by the public. After all, this new car was a complete departure from the Mustang that had come before it. Although this new Mustang certainly seemed to align with what was selling in the current automotive marketplace, there were some execs who were concerned that this radical new design would not be well-received under the Mustang moniker.

As a result, Ford’s promotional department strongly encouraged giving this new car a new name. Ford’s North American Operations Public Relations Office issued a written suggestion in August 1972 that this new car be dubbed the “Mustang II.” The “II” in the name would symbolize a new generation of the brand – not unlike Chevrolet’s predication that each successive generation of the Corvette carries a unique identifier – C1, C2, C3, and so on.

This new naming convention was presented to Henry Ford II and he embraced the name immediately. Considering that he’d originally envisioned the original Ford Mustang as the “Thunderbird II,” it seemed fitting to brand the next-generation pony car as the successor to the earlier model.

The Mustang II debuted in August 1973, and was initially praised by automotive critics as being “a stroke of genius” and “revolutionary.” Motor Trend Magazine recognized the Mustang II as “the Car of the Year” for 1974. What’s more, when the Arab oil embargo in October 1973 caused the price of a barrel of oil to skyrocket, providing a small, fuel-efficient car to the American public made the new Mustang a hot commodity in the automobile marketplace.

NEXT: More research on the Second Generation Mustang