What was the mystery message written on the mummy's wrappings?

A puzzle confounded Egyptologists when an unidentified ancient language was found on a mummy's bandages in the 1800s. Solving it took decades but rewarded scholars with valuable insight into the authors—the Etruscans.

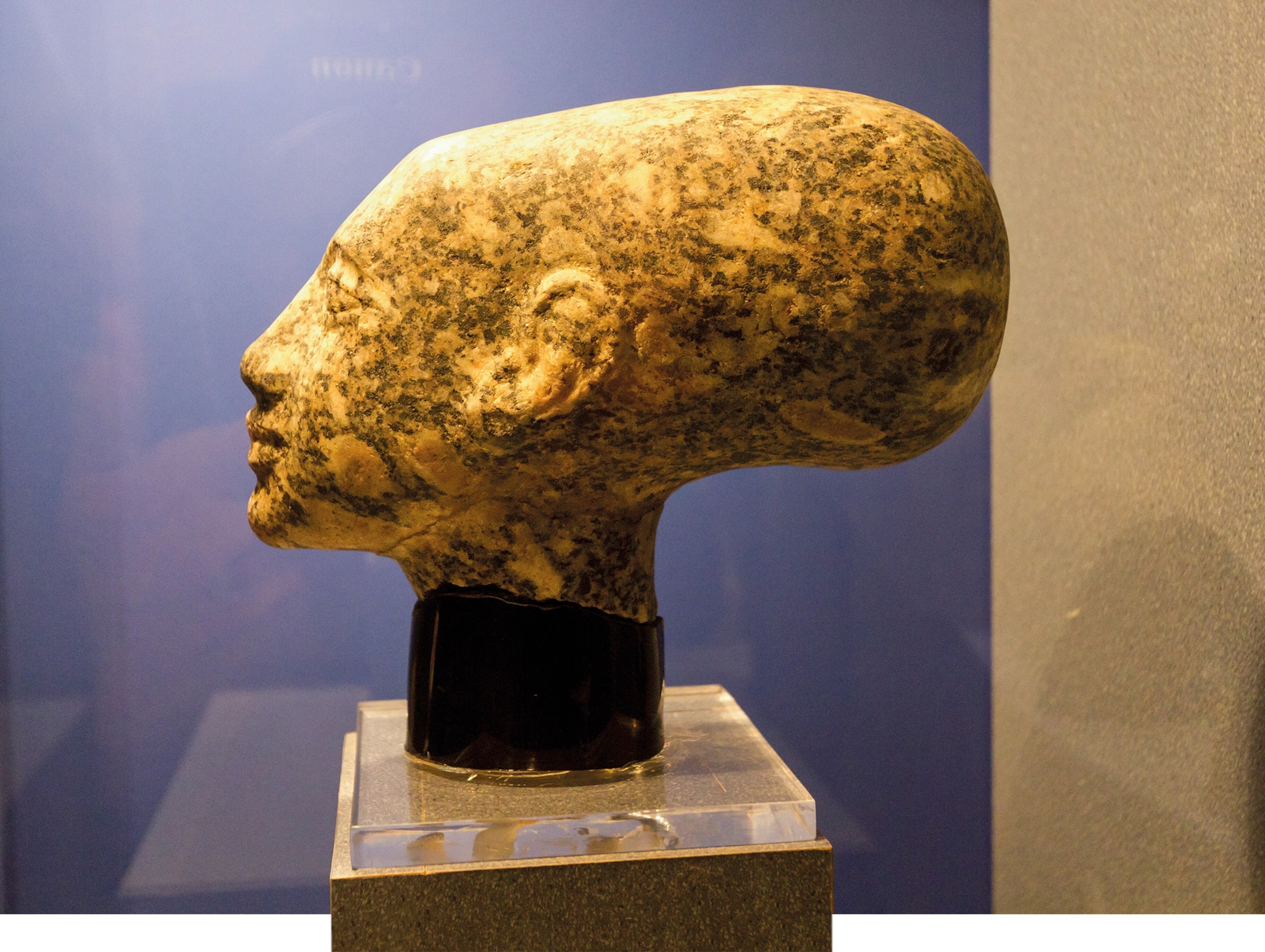

In 1868 the Museum of Zagreb in Croatia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, acquired an Egyptian mummy of a woman. Her previous owner had removed her wrappings but held on to them. She had been an ordinary person, not royalty or of the priestly class. Her wrappings, however, held a fascinating puzzle. There was writing on the linen strips, but German Egyptologist Heinrich Brugsch noted that they were not Egyptian hieroglyphics. It was a script unknown to him.

Two decades later, in 1891, museum authorities agreed to send the wrappings to Vienna to see if they could translate the markings. The bandages were examined by the Austrian Egyptologist Jakob Krall, who was able to finally break the code: The letters were not Coptic, as some had speculated, but Etruscan, the words of a culture that had dominated pre-Roman Italy. Whoever had wrapped the mummy centuries before had used strips torn from an Etruscan linen book.

Long recovery

The discovery was sensational. References to Etruscan linen books can be found in many classical works, but surviving specimens had been impossible to find. The arid climate of Egypt coupled with the desiccants used to dry out the mummy had created a perfect environment to preserve the fragile textile. The mummy’s wrappings were not only the first linen Etruscan text found intact but also the longest text ever found in Etruscan. It could be a gold mine of information on the culture.

(The modern calendar was inspired by the Etruscans and evolved by the Romans.)

Krall’s identification of the Linen Book of Zagreb (also known by its Latin name, Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis) raised many questions about its contents and when it was written. Of equal interest was how an Etruscan book came to wrap an Egyptian mummy.

Etruscan enigmas

The modern Italian region of Tuscany corresponds roughly with the ancient Etruscan homeland of Etruria. Emerging in the eighth century B.C., Etruria traded with Greek colonists and developed a sophisticated culture of metal-working, painting, and carving. Trade brought Etruria goods, Greek gods, and the Euboean Greek alphabet. The Etruscans adapted it to create their own script, which was written from right to left.

Grave goods

The Etruscan language is almost unique among European languages. Nearly all of them (including English) are derived from Indo-European tongues that arrived in Europe thousands of years ago. Etruscan, however, is an outlier: a rare case of a language that predated and survived the Indo-European influx.

Early Roman history is intertwined with that of Etruscans, who served as the city’s earliest kings. Etruscan words found their way into Latin—phersu, the Etruscan word for “mask,” is the root word for “persona” and “person.” The growth of republican Rome’s power, however, would consume Etruscan society, leaving just its artifacts, vivid tomb art, and inscriptions that fewer and fewer people could read.

First-century Roman emperor Claudius was a student of Etruscan, and one of the last people in classical antiquity able to speak and read it. Claudius even wrote a 20-volume history of the Etruscans, a work that has not survived to the modern age.

Body of evidence

Before being torn into bandages, the Linen Book of Zagreb was a sheet about 11 feet long covered with 12 columns of text. The part recovered from the bandages is thought to correspond to about 1,330 words— about 60 percent of the original text. Prior to the linen book’s discovery, Etruscan experts had only been able to study the ancient language based on some 10,000 short inscriptions, but Krall’s identification of the linen book’s language in 1891 greatly increased the amount of available text.

θucte. ciś. śariś. esvita. vacltnam

“On [August] 13, conduct the consecration according to the rite.”

culścva. spetri. etnam. i.c. esvitle. ampn/ eri

“Keep/Guard the doors [open?] then, for the consecration.”

celi. huθiś. zaθrumiś. flerχva. neθunsl śucri. θezeric.

“On September 24th, sacrificial victims for Nethuns [Neptune] are to be presented.”

At first, scholars believed the linen book was a funerary work, which led to speculation that it was somehow linked to the body it once wrapped. The mummy had been purchased in the 1840s in Alexandria by a Croatian man named Mihail Baric. He kept the mummy in his Vienna home. After his death, the mummy and its wrappings were donated to the museum in Zagreb.

The Etruscan linen book was not the only text that formed part of the mummy’s wrappings. A papyrus of the Egyptian Book of the Dead was also used to wrap the body. This Egyptian work references a female figure, named Nesi-Khons (“the mistress of the house”), whom scholars now believe to be the woman whose body was mummified. In the late 20th century, it was established that she lived sometime between the fourth and the first centuries B.C. and died in her 30s.

(How Egyptians made mummies in 70 days or less)

The linen book’s black ink was made from burnt ivory, with titles and rubrics in red written in cinnabar, a scarlet ore used in pigments. The Etruscan text was obscured in many places by the balsam used in the mummification process, but in the 1930s, advances in infrared photography allowed 90 more lines of the Etruscan to be deciphered, further clarifying what scholars believed the book’s role had been: a ritual calendar detailing rites enacted throughout the year.

The instructions in the Etruscan book center on when certain gods should be worshipped and what rites, such as a ritual libation or animal sacrifice, should be performed. Among the specific deities mentioned is Nethuns, an Etruscan water god, a figure closely related to the Roman sea god, Neptune. The text also references Usil, the Etruscan sun god, similar to Helios, the Greek solar god.

Further study identified words and names that pinpoint the place of its composition. Etruscan experts believe the linen book was made near the modern-day Italian city of Perugia. While the linen itself has been dated to the fourth century B.C., textual clues place the writing to much later. The inclusion of the month of January as the start of the ritual year is the strongest indicator that the text was written sometime between 200 and 150 B.C. If this later dating of the text is correct, it opens a window onto a way of life that was soon to be swept away by the expansion of Roman power.

A ritual annual

Scholars still don’t know exactly how this Etruscan text ended up in Egypt. Several hypotheses have been put forward. One is that the city of Alexandria, where the mummy was purchased in the 19th century, was a focus of international trade between the fourth and the first centuries B.C. In a cosmopolitan port city, texts from other cultures would not have been a rarity; her body was simply mummified with the material available at the time. According to this theory, there is no special link between the book itself and the beliefs of the dead woman. The mummifiers just used what was around.

Another theory takes a radically different view, pointing to Etruscan statuary that depicts linen books being placed in tombs, much as Egyptians placed the Book of the Dead in theirs. If the dead woman was of Etruscan ancestry, her relatives might have buried her according to the customs of both her adoptive and ancestral cultures, using both the Egyptian Book of the Dead and the Etruscan linen text.