Video: Why a scared expression brings a survival advantage

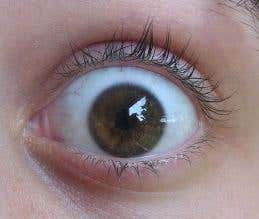

You wrinkle your nose and squint when you see a dead rat in the road, but open your eyes, nose and mouth wide when you see a live one in your bedroom.

Why? Common facial expressions like disgust and fear, new research suggests, do more than just convey how you are feeling – they alter your sensory relationship to the world around you.

Charles Darwin, noticing that some facial expressions seem to hold across cultures and even species, proposed that they function to improve certain senses. Now Joshua Susskind and colleagues at the University of Toronto, Canada, have put that to the test.

Advertisement

The team wanted to know if fear, and its apparent sensory opposite, disgust, changed the way we use our senses. They hypothesised that the former, with its open eyes, raised eyebrows and gaping mouth, led to greater sensory acquisition, allowing greater vigilance, and disgust, with the face all scrunched up, led to less.

Face of fear

In one experiment, volunteers had to identify when a dot entered their visual field, while they maintained fearful, neutral or disgusted expressions.

In another, also with these expressions, they had to move their eyes as quickly as possible between two targets about 30 centimetres apart on a computer screen while their eyes were tracked.

The amount of air that could be breathed in while showing fear and disgust was also measured.

In each case, the researchers found, the expression of fear – or the “Home Alone face”, as Susskind nicknames it – let significantly more of the world in.

Speedy senses

The open eyes allowed quicker detection of objects on the periphery, as well as faster eye movements back and forth, while an open nose took in more air with each breath without any extra effort. An MRI scan confirmed the difference in the space in the nasal cavity.

“These changes are consistent with the idea that fear, for example, is a posture towards vigilance,” says Susskind, “and disgust a posture towards sensory rejection.”

Further experiments, he says, will explore to what extent the brain actually uses this extra information to enhance performance.

Cognitive neuroscientist Elizabeth Phelps at New York University, US, thinks the research could open up a whole new way of thinking about facial expressions. “What was nice was the number of different ways they got at this question,” she says.

Journal reference: Nature Neuroscience (DOI: 10.1038/nn.2138)