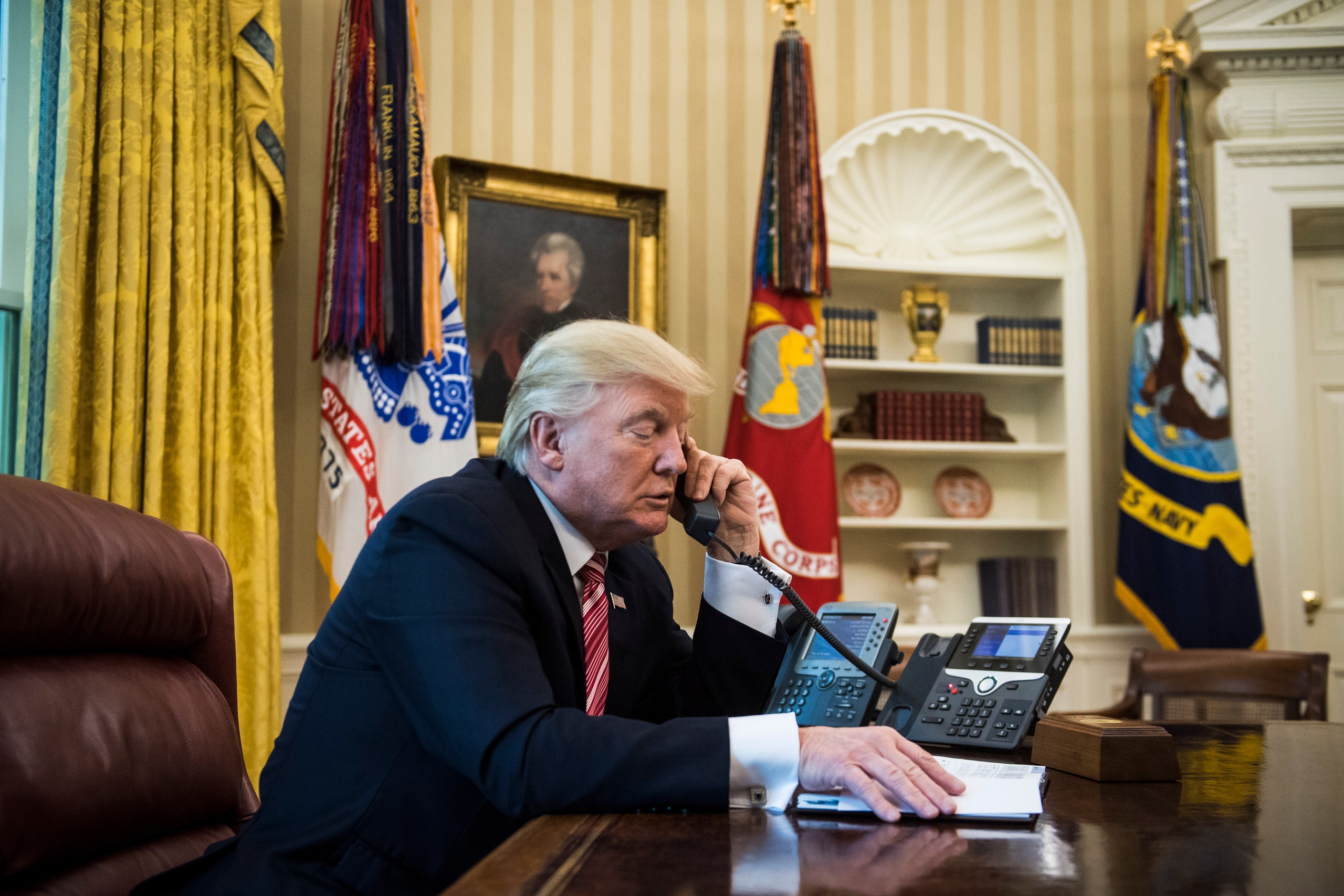

There is a moment in Donald Trump’s phone call, a week after his Inauguration, with the Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull—the transcript of which was obtained by the Washington Post—when Trump seems to think he understands his counterpart. It comes, tellingly, at a point when he also decides that the Prime Minister has been lying to the public. The two men had been discussing a deal, concluded under the Obama Administration, for the United States to take in up to two thousand refugees whom Australia had detained on the islands of Nauru and Manus. They were not being held there because they were “bad people,” Turnbull says, but because Australia has a policy of not letting in refugees who arrive by boat: “If they had arrived by airplane and with a tourist visa then they would be here.”

“What is the thing with boats?” Trump says. “Why do you discriminate against boats? No, I know, they come from certain regions. I get it.”

He thought he got, in other words, that Turnbull didn’t want to discriminate against boats but did want to discriminate against people coming from “certain regions”—regions that, Trump seemed to imagine, were both full of undesirables and a boat’s length from Sydney. (Whether his epiphany made any geographical sense is another matter.) That would, after all, be a version of the semantic trick that Trump had tried himself when he was asked, in an interview with Lesley Stahl, how he would get a ban on Muslims entering the United States past the courts: “We’ll call it territories, O.K.?”

That line did not impress the majority of judges who have heard challenges to Trump’s executive order blocking, in its latest iteration, refugees and people from six Muslim-majority nations from entering the United States; indeed, a number of decisions staying the order cited it as an example of the order’s “bad faith”—a standard that would give the courts, which usually defer to the executive on immigration matters, a rationale for reviewing Trump’s action. And his projection of a parallel form of bad faith onto Turnbull was accompanied by remarks that may provide fodder for opponents of the executive order when it appears before the Supreme Court, this fall.

For example, Turnbull had begun the call by complimenting Trump on the way the first version of his executive order favored Christians, although the provision in question (which was removed from the second version) only specified religious minorities in countries that were the sources of refugees. Trump responded by rambling on about how the Obama Administration was, supposedly, much harder on Christian refugees than on Muslim ones.

Perhaps Trump thought that Turnbull would respond to his “I get it” with a chummy acknowledgment of shared goals and mendacity. Instead, the boats-for-regions comment seems, for a start, to have alarmed Turnbull, not least because it would have definitively demonstrated to him that Trump had not really been listening to, or understanding, a word he said. Turnbull had already told him, earlier in the call, “It is because in order to stop people smugglers, we had to deprive them of the product. So we said if you try to come to Australia by boat, even if we think you are the best person in the world, even if you are a Noble [sic] Prize winning genius, we will not let you in. Because the problem with the people—”

The transcript indicates that Trump interrupted him at the point to say, “That is a good idea. We should do that too. You are worse than I am.” It is not clear what Trump meant by “that.” Perhaps it was just the idea of keeping as many people as possible out of the country, whether they were what he referred to as “bad hombres,” in a call the same week to the President of Mexico, or Nobel Prize winners. (Australia’s off-shore detention practices are untenable, have been subject to criticism on humanitarian grounds, and in many ways flout the country’s own commitments to refugees—hardly something, one would think, to be envied.) Trump portrays all of the refugees as potential terrorists—“Are they going to be the Boston Bombers in five years?” But Turnbull, presented with the President’s incomprehension a few minutes later, gamely tries again:

Turnbull keeps making Trump angrier and angrier; Trump says that it was his most “unpleasant” call of the day—much worse than talking to Putin. It likely didn’t help Trump’s mood that Turnbull called Australia a “generous, multicultural” nation, or that he said that Obama “drove a hard bargain”—Australia also agreed to take refugees from Central America. The reference to Obama set Trump off on a petty rant about how pretty much every deal concluded before he entered the White House was “stupid,” and how this one in particular was “horrible” and, indeed, “disgusting.” And, coming right after his executive order, “It makes me look so bad.” Also, “I will be seen as a weak and ineffective leader.” A leader of whom, toward what? When Turnbull appeals to him as a fellow “transactional” businessman—asking him to act like a statesman might have seemed out of the question at that point—and says that sticking to the deal shows that he stands by commitments, Trump replies that, instead, it “shows me to be a dope.”

What is most striking, though, is the actual practical disagreement between the two men. Trump never seriously threatens to renounce the agreement; his objection is to the idea that Turnbull, or anyone, would claim that it was, as the Prime Minister put it, “consistent with the principles set out in the Executive Order.” (“No, I do not want [sic] say that. I will just have to say that unfortunately I will have to live with what was said by Obama. I will say I hate it,” Trump replied.) Their different views on that point thus reveal a great deal about what the principles of the executive order actually are.

Under the agreement with Australia, the United States is not actually obliged to take any of the people at all; it had only agreed to look at their cases and admit them if they passed a vetting process that could be as extreme as Trump wanted it to be. This speaks to one of the central issues with the travel ban: whether it is part of a legitimate effort to make sure that unvetted, unknown people don’t enter the United States or is meant to exclude Muslims wholesale. The source of Turnbull’s frustration is that he is arguing with Trump as though the former, respectable reason were the true one. Trump, though, makes it clear that he really doesn’t care how much the refugees on Nauru and Manus are vetted, or whether, as Turnbull keeps saying, Australia knows who they are. The problem wasn’t danger; it was identity.

“I hate taking these people,” Trump tells Turnbull. “I guarantee you they are bad. That is why they are in prison right now. They are not going to be wonderful people who go on to work for the local milk people.”

“I would not be so sure about that,” Turnbull says. (He may, in the moment, have had a better idea of what Trump meant by “milk people” than one gets from reading the transcript.) Trump’s assumptions about the bad character of anyone detained by the authorities, for any reason, are hardly surprising at this point. He expressed them clearly enough when he encouraged police officers on Long Island to inflict head injuries on the people they arrested. His views are, to say the least, an unsound basis for either immigration or foreign-policy decisions. (An example of that comes in his encouragement of the police abuses in Duterte’s Philippines.) But his dismissiveness is especially frustrating given that Turnbull has already told him, again and again, that these people are not “in prison” for any crimes; Trump, though, keeps comparing the situation to the Mariel boat lift. (“Nobody said Castro was stupid.”) A couple of minutes later, Trump mentions, once again, the Boston Marathon bombers: “They said they were wonderful young men.”

“They were Russians,” Turnbull says. “They were not from any of these countries.”

“They were from wherever they were,” Trump replies, imagining, perhaps, any number of lands, full of people he hated, just a boat ride away.