This commentary was published in commemoration of International Fact-Checking Day 2024, held April 2 each year to recognize the work of fact-checkers worldwide. Jisha Krishnan is chief editor at First Check, an India-based fact-checking organization that specializes in health care.

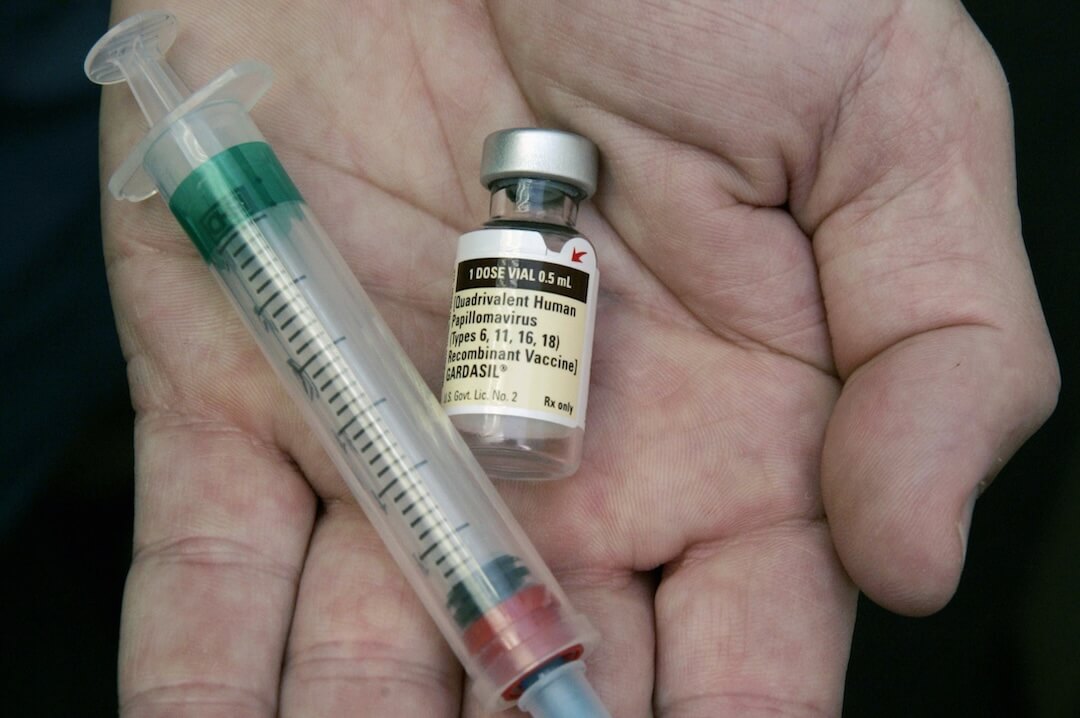

Earlier this year, India’s finance minister announced plans to launch a national drive to vaccinate girls between 9 and 14 years against the human papillomavirus, called HPV, which causes cervical cancer. It is the second-most common type of cancer in women in India. Nearly 123,907 Indian women are diagnosed with cervical cancer every year and an estimated 77,348 die from the disease.

Studies show that HPV vaccines are highly effective in preventing cervical cancer. Yet 18 months after India launched its first HPV vaccine, getting adolescent girls to take the shot is proving to be an uphill task. “What if it causes reproductive health problems?” “What if it makes the girls sexually active?” “What if it’s just another money-making exercise for the hospital?” The fears and mistrust largely stem from social stigma associated with reproductive health issues, exacerbated by false narratives about the vaccine on social media platforms.

In Africa, people echo the same fears and mistrust about the HPV vaccines. Most of the misconceptions stem from worries about the vaccine’s impact on fertility and population control, said a young public health professional from Nigeria, who is a member of our global network at First Check.

Make no mistake, though — this is not just an HPV vaccine issue. We saw similar examples worldwide with the COVID-19 vaccines during the pandemic, and more recently, with the resurgence of measles cases in the U.S.; that disease was declared eliminated from the country in 2000. Yet the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated that as of March 14, a total of 58 measles cases had been reported by 17 jurisdictions. Last year, the CDC reported a 10-year low in routine childhood vaccination rates, which put nearly 250,000 kindergartners at risk for measles.

In his latest book “The Deadly Rise of Anti-Science: a Scientist’s Warning,” Dr. Peter Hotez, an acclaimed scientist and pediatrician, refused to call the anti-vaccination rhetoric “misinformation” or “infodemic.” He called it an anti-science movement, because it is organized, well-financed and politically motivated.

As fact-checkers and journalists, we know this. Yet health fact-checking continues to be a niche area of work. Niche as in “denoting products, services, or interests that appeal to a small, specialized section of the population.”

Health fact-checking is still not part of the mainstream discourse. It wasn’t last year either, when I wrote a piece for Poynter on the occasion of the 2023 International Fact-Checking Day.

Over the last few months in India, the tension between traditional and modern medicine has come to the boil, with the Indian Medical Association taking one of the biggest pharma companies to court for making false and misleading claims in advertisements about curing a wide range of ailments, from the common cold to autism. Last month, the Supreme Court of India issued a contempt notice and directed Patanjali Ayurved, the Indian multinational conglomerate co-founded by a purported yoga and ayurveda expert, to cease all electronic and print advertisements.

Perhaps the laws will evolve to keep up with the health misinformation landscape. But what about health-related attitudes and behaviors that are essentially anti-science? Because unless that changes, health misinformation will continue to spread — online and offline — eroding trust among doctors, patients, governments, institutions, and societies.

Health is wealth, they say. That’s true of individuals and countries. Unless we invest in health care, and strengthen our fight against health misinformation, true progress is impossible. We need to work together and collaborate with experts to make credible, timely, relevant, understandable and actionable health information easily accessible for all.

At First Check, a verified signatory of the International Fact-Checking Network, we currently have 53 experts from 24 countries who have volunteered to help address global public health challenges. The challenges are only going to get bigger with the rise of generative artificial intelligence, and in particular ChatGPT.

Albert Einstein famously said that we cannot solve our problems with the same thinking that created them. This International Fact-Checking Day, let’s resolve to rise to the next level of combating health misinformation.