The global network of fact-checkers is large and diverse, International Fact-Checking Network director Angie Drobnic Holan said on International Fact-Checking Day. And an accompanying State of the Fact-Checkers Report showed that raising money and addressing harassment remained that network’s top concerns.

International Fact-Checking Day, which was April 2, is a global initiative recognizing accurate information’s important role in an interconnected world. During an April 2 Zoom call with network signatories, Enock Nyariki, the network’s community and impact manager, presented the 2023 State of the Fact-Checkers report. Guests Govindraj Ethiraj, who started his nation’s first data journalism initiative, IndiaSpend, and Peter Cunliffe-Jones, a longtime foreign correspondent for The Economist, The Independent and the Paris-based Agence France-Presse news agency, reflected on fact-checking’s progress and challenges.

One hundred thirty-seven organizations across at least 69 countries completed the survey, which ran January to March 2024. In 2023, 46 groups responded.

Some key findings:

There’s a nonprofit majority. Nonprofit organizations continue to outnumber for-profit signatories in the network, 53% to 40.9%.

(Chris Kozlowski/Poynter)

Many operations are small. Sixty-eight percent of fact-checking organizations have 10 or fewer employees; 6.6% employ 31 or more people.

(Chris Kozlowski/Poynter)

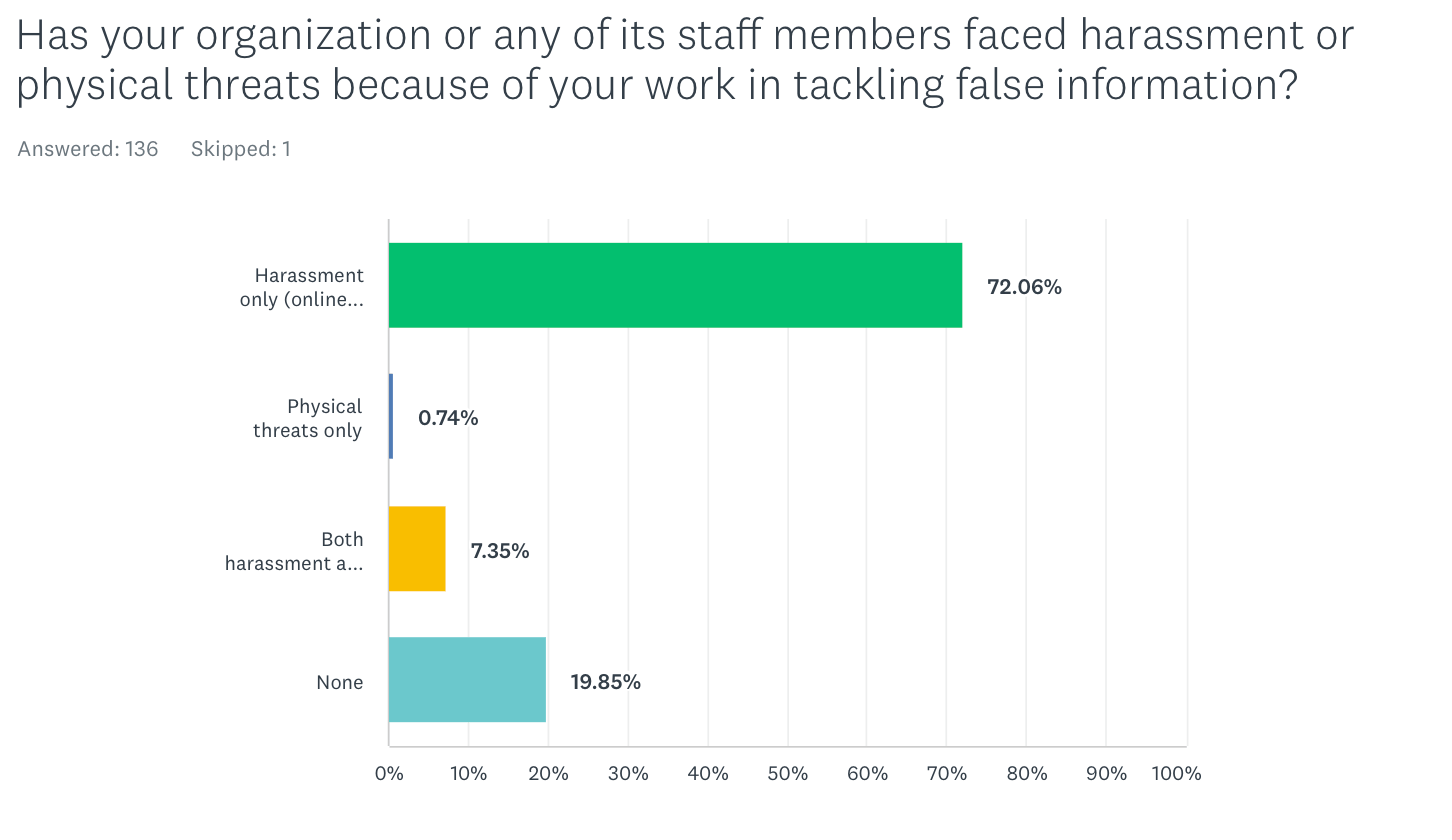

Harassment continues. About 72% of surveyed signatories reported facing harassment in 2023 because of their fact-checking. Most attacks, directed at groups and fact-checkers, came online, but 7% involved physical threats. A majority of organizations surveyed said the volume of attacks was equal to 2022 or greater.

(Chris Kozlowski/Poynter)

Financial focus. Fact-checkers said their biggest challenge is raising money to sustain their work and to become financially sustainable. Grants now benefit more fact-checkers than the Meta program, backing about 87% of survey respondents.

(Chris Kozlowski/Poynter)

Holan said funding challenges and harassment are challenges fact-checkers share with journalism writ larger and civil society.

“I’m personally very unsatisfied that we haven’t been able to come up with better strategies for dealing with online harassment,” she said. “It feels like this is a problem that won’t go away. At GlobalFact 11 this summer in Sarajevo (Bosnia and Herzegovina), I know we’re going to have at least one and possibly more panels on dealing with harassment because it is such an intractable problem.”

Hot topics. Elections and politics and public health were signatories’ most fact-checked topics (95.62% for both), followed by social issues (93.4%) and economic issues (84.6%).

(Chris Kozlowski/Poynter)

Eyeing artificial intelligence. About 47.4% of surveyed signatories said they had established or were working to establish editorial guidelines for using AI chatbots such as ChatGPT and Google’s Bard in their work.

(Chris Kozlowski/Poynter)

The guests saw progress and challenges for fact-checkers. Cunliffe-Jones said fact-checking is happening now in places where it once seemed unimaginable, although there remain places that need fact-checking and don’t have it. He also said more fact-checkers are following the IFCN Code of Principles.

“It’s not just about people doing fact-checking or claiming they do fact-checking, we need to do it in the right way,” Cunliffe-Jones said. “And that’s what the code is about. And that’s why the growth of the IFCN to me is so important.”

Ethiraj said fact-checking is growing along with digital infrastructure and social media. The world has about 5 billion social media users and a growing number of smartphones. In India, he said, 800 million smartphones are in use, and more than 1 billion are in use in China. The gadgets make seeing and spreading disinformation easier, he said.

“So, the point is that the spread of misinformation, thanks to the infrastructure, has also been very rapid in these last few years, which in turn has necessitated the need for greater fact-checking,” Ethiraj said.

What gets fact-checked has also evolved, Ethiraj said. In 2014, when factcheck.in started, fact-checking focused on claims made in public life using data and evidence that was already in the public domain, mostly government data sets. Now, though, fact-checkers are increasingly checking harmful images, videos and deepfakes.

Cunliffe-Jones said fact-checkers will need to find ways to get their work into as many languages as they can, perhaps leveraging new AI tools to do it.

They will also need to cope as the public tries to discern IFCN Code of Principles-following fact-checkers from groups, sometimes backed by governments, that present imitations of fact-checkers to subvert real fact-checking.

“There’s a lack of awareness amongst the wider public about the IFCN code, which distinguishes between what we’re doing (and) what the government does,” he said. “That, to me, that’s a really significant long-term challenge. Because if people don’t recognize differences, (between what) we do (and) what they do, we’re all just voices chatting in the noise.”